Who’s Winning, and Losing, In Port KC Development Projects Port KC is a Big Player in KC Development. But What are the Costs?

Published April 13th, 2016 at 2:45 PM

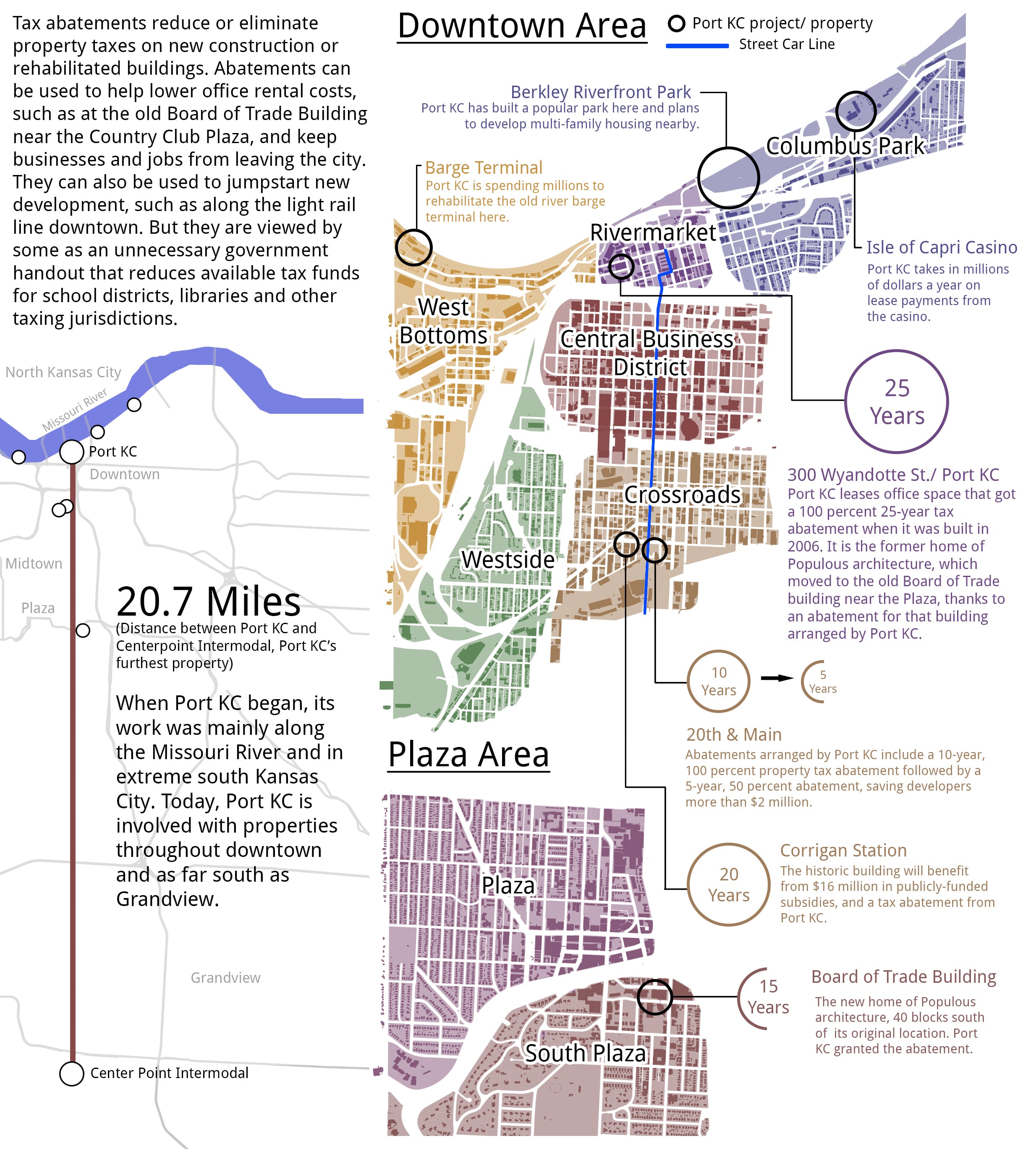

Above image credit: (Illustration: Coleman Stampley | Flatland)When Kansas City needed help to keep a prestigious global architecture firm from leaving town last year, it reached out to an unlikely partner — the Port Authority of Kansas City.

The loss of the firm, Populous architecture, which designs sports arenas around the world, would have been a huge blow to Kansas City and its image.

So the port authority — a state agency whose commissioners are appointed by City Hall — swaggered up to the plate.

The agency cobbled together a 15-year property tax abatement for redevelopment of the old Board of Trade building near the Country Club Plaza. By saving money on taxes, the developers were able to offer Populous an attractive lease agreement that kept them from leaving town.

Since then the port authority — often at the city’s request — has become a big player in Kansas City redevelopment thanks to its ability to offer tax incentives with relatively little accountability. This has played out in a number of deals over the last few months, and it could be the back story of other deals to come, much to the dismay of tax abatement critics.

“Make no mistake about it, these (port authority commissioners) are corporate developers,” said R. Crosby Kemper III, Kansas City Public Library director and perhaps the city’s most ardent abatement opponent.

The trend continuing under the port authority, he said, represents a “massive shift of taxes onto the working poor.”

Michael Collins, president and CEO of the port authority, has been at the center of an anti-abatement storm in recent months. He says abatement critics just don’t get the mechanics of the deals.

All the port authority is trying to do is retain jobs and keep Kansas City competitive on a global scale, he said.

In fact Collins, a former staffer for Sen. Kit Bond, is downright evangelistic about development: “I just see opportunity, a plethora of opportunity that Kansas City is hopefully going to love and cherish.”

Expanded Mission

As late as 2011, the port authority was the red-headed stepchild of the city’s Economic Development Corporation and running low on cash. Years of scandal, dysfunction and unfulfilled plans had stripped away respectability.

But now, five years later, it’s a financially secure stand-alone agency with a new name – Port KC. It has a new leader in Collins, a fresh batch of commissioners and an aggressive new mission to create jobs and spark development.

Indeed, this is not your father’s port authority, where a former director once took a bribe and did prison time; where previous commissioners voted to hire their own companies; and where a $15 million deal with a Donald Trump went nowhere.

Port KC’s 10-year citywide plan calls for spending $133 million on development. And clearly, not just along the river.

Eye of the Storm

The reborn Port KC labored in relative obscurity until a few months ago, when minority groups and advocates for taxing jurisdictions such as the Kansas City Public Schools had an epiphany.

These activists had been turning up the heat on the traditional City Hall tax abatement agencies, arguing that decades of abatements had cut school districts, libraries and other taxing jurisdictions out of millions in future income.

Late last year, they even mowed down one of the less onerous abatement projects to come along in a while. Their petition drive nixed plans to renovate an old Crossroads building into an environmentally friendly home for yet another architecture firm, BNIM.

“We’re not a workaround,” — Michael Collins, president and CEO of the port authority

Given the political heat on other city abatement agencies, it appears Port KC quietly became a work-around for developers, allowing the tax-abatement process to continue, well … unabated.

“We’re not a workaround,” Collins insists, arguing that his agency has created 1,800 jobs in the past year and leveraged $16 in private development funds for every dollar in taxes it has abated.

Some advocates for the school district and representatives of the East Side, which rarely benefits from such deals, don’t see it that way. They showed up at a Port KC commissioner’s meeting for the first time in February.

Jan Parks, who chairs the education task force of the Metro Organization for Racial and Economic Equity, boiled the message down to a sound bite: “Taxing jurisdictions should not be banks for economic development.”

Jackson County officials, who collect those taxes and redistribute them to schools, the blind pension fund and others, aren’t convinced either.

“We all support economic development, particularly job creation,” said Calvin Williford, chief of staff for Jackson County Executive Frank White. “Michael Collins is smart and capable and is doing what he believes is helpful to economic development. But I think he is going about it the wrong way.”

The criticisms are aimed in part at how Port KC abates taxes. Unlike at other city abatement agencies, Port KC uses what some see as a sleight-of-hand maneuver.

Because Port KC itself is exempt from property taxes, developers seeking abatements transfer their property to the port, which then leases it back to the developers.

At the old Board of Trade building for example, where the Populous firm moved, Collins said the city asked Port KC to step in and take ownership of the building. Port KC then issued bonds covering the cost of the transaction, and leased the property back to the developer.

CASE No. 1: 300 WYANDOTTE AND BOARD OF TRADE

And last year was not the first time city officials scrambled to keep Populous in town.

In 2006, long before they moved into the old Board of Trade building, the city arranged what amounted to a rent subsidy for Populous in a new office building in the River Market area.

That was made possible by a 25-year tax abatement the city granted for the building at 300 Wyandotte St.

To make the deal work, the city in essence bargained away an estimated $10 million in future taxes on the building that would otherwise have gone to Jackson County school children, blind pensioners, and the mentally ill.

The complex, complete with a city-financed 400-space parking garage, was designed by and custom built for Populous. They occupied 70 percent of the building until two years ago, when a dispute with the building’s owners over a new lease agreement caused them to pull up stakes.

Today the River Market building sits mostly vacant and appraised at a fraction of its original value. The new owners are in default on their loan.

Port KC – now one of the few remaining tenants at the 300 Wyandotte building – quickly put together another deal at the old Board of Trade building that city officials believe kept Populous from leaving town all together.

The city came to Port KC, Collins said, because they were the only ones who could make the deal work.

“Competing abatements like that are totally nuts; there’s no reason for that,” said Kemper, of the Kansas City Public Library.

Collins acknowledges the criticism.

“I understand the argument over moving from one abated property to another abated property,” he said. “But we saw this as an opportunity to keep these jobs – jobs of a significant magnitude – in Kansas City.”

All together, the abatements amount to an estimated $10 million for 300 Wyandotte over the next 25 years and millions more – it’s unclear at this point how much more — in deferred taxes on the Board of Trade building, all to keep one company and hundreds of high-paying jobs from leaving town.

“Competing abatements like that are totally nuts; there’s no reason for that.” — R. Crosby Kemper III, Kansas City Public Library

Should it have cost that much to keep Populous and was it worth it?

Populous referred questions to Sean O’Byrne of the Downtown Council, who helped put the Board of Trade deal together.

“Populous has been a great corporate citizen,” he said, adding that they negotiated in good faith to keep their offices in the River Market.

But did the city have to give up as much as it did in taxes to keep them here?

O’Byrne doesn’t know for sure, he said. Only Populous does.

Who Knows What?

Jackson County’s Williford says some Port KC abatements are done in relative secrecy.

“To have these third parties come in and redirect these funds without the input of the public feels very counter to good public policy,” Williford said. “It does great harm.”

A recent abatement at 20th and Main is his Exhibit A.

Earlier this year, Port KC agreed to a lease-back deal for a $22 million, 112-room extended-stay hotel at 2001 Main St.

Port KC gave the developers a 10-year, 100 percent property tax abatement followed by a five-year, 50 percent abatement, saving them more than $2 million.

The city kicked in another $300,000 to demolish a street ramp and helped relocate a billboard.

After 15 years, the tax-exempt Port KC will transfer the property back to the developers, a subsidiary of Sunflower Development Group.

Collins said the city provided Port KC with a financial analysis showing that without the exemption, the hotel would not be built and the unimproved lot would generate only $48,000 over 15 years for the school district, the library and other jurisdictions.

But Williford said Port KC never consulted the county about the project, as other city abatement agencies do. In fact, he said, county officials learned some of the details only through press reports.

And some of the incentives in the deal “concerned” them.

Williford said efforts to talk to Port KC went nowhere, so they asked the developer.

Williford said the developer told county officials that Port KC’s abatement agreement prohibited them from discussing it, a claim Port KC’s Collins denies.

In December, frustrated county officials said they made a last-ditch effort to get the details. They sent Port KC a request under the state open records law – a tool more often used by snoopy, frustrated journalists than by bureaucrats.

Port KC denied the request two days later, telling county officials that the county’s previous threats to sue Port KC over abatement procedures gave them the right to do so.

Williford called that reasoning “very flimsy,” although he left open the option of suing Port KC in the future.

“We are not afraid to use whatever tools are necessary to make sure taxpayers are fully represented in this process,” he said.

Collins and Port KC offer a decidedly different version, and they back up parts of it with letters and copies of emails.

The county knew all about the deal, Collins said, and the emails prove it. In fact, Port KC officials noted in one letter to the county’s lawyer that the county doesn’t understand the state laws governing abatements by port authorities.

Counties have no power under state law to block port authority abatements, Port KC said in its letter, adding that attempts by Port KC to negotiate with the county have been met with “blatant obstructionism.”

Still, Port KC said, it has taken additional actions to make sure abated developers pay more in lieu of taxes than state law requires, as they did in the Board of Trade case.

While that deal abates taxes for 15 years, it also requires annual payments to the county ranging from $250,000 to $330,000.

Political Cover

The whole Port KC process – even if it complies with state law — needs a hard look, says Williford. “There are fewer checks and balances than the public deserves to have when you are giving away their tax dollars.”

And indeed, the Port KC process is not as rigorous as at other abatement agencies.

For example, other city agencies must show that the projects they are abating would not be built “but for” the tax break.

Port KC has used such analyses on some projects, but there is no requirement for them to do so. Under state law, they have the power to abate taxes even if developers could profit without them.

And, unlike other city abatement agencies, Port KC’s board of commissioners does not include members who represent taxing jurisdictions that would lose money from abatements, such as the school district, libraries and mental health facilities.

In addition, Port KC abatements, unlike those given by other city agencies, do not require approval by the City Council.

In other words, while the mayor and city council choose commissioners for the state-chartered port authority, those same politicians can dodge direct responsibility for the abatements those commissioners grant.

“There are fewer checks and balances than the public deserves to have when you are giving away their tax dollars.” — Calvin Williford, Jackson County

Williford says Port KC is likely to continue such generosity to developers because of the actions of Mayor Sly James.

The mayor, who many see as a decidedly pro-abatement politician, has acquired signed but undated resignation letters from all of Port KC’s current commissioners, a spokesman for the mayor confirmed.

“Wow, that’s amazing,” Williford said when told of the letters. “Obviously that’s unprecedented for a mayor to have that much power.”

James was not pleased with Williford’s suggestion that Port KC commissioners would be inclined to check the wind direction out of the mayor’s office before voting on the next abatement deal.

“I don’t micromanage boards and commissions and I don’t strong-arm any appointees,” James said in a statement.

He added that he had only once “accepted a pre-submitted board resignation letter,” and that was because an appointee “exceeded the scope of his responsibilities.”

“Port KC is a state agency,” the mayor added, “and inferring that the Mayor of Kansas City can dictate the policy of a state agency is disingenuous at best.

“The issue the County has with Port KC appears to be a difference of opinion about Port KC’s mission. I’d prefer in-person discussions…rather than baseless accusations and insinuations through the media.”

James is right to the extent that not all Port KC abatement votes by the commissioners have been unanimous.

But that kind of rhetoric is not likely to cease anytime soon, given the passion on both sides of the argument.

Critics have a basic misunderstanding of abatements, Collins said. Abatements are sometimes needed not because developers simply want a break, but often because banks won’t loan them money to redevelop without them.

He added that critics often forget that Port KC is not abating personal property taxes on equipment installed in new buildings, and that the salaries for the jobs they attract and maintain feed into the city’s earnings tax.

Besides, he added, Port KC has only approved about 30 percent of the abatement deals that have come before it, and it’s done so out in the open.

“We are transparent, we are not a back door,” Collins said.

As for Williford, he makes his view clear: “It would be our hope that Port KC spend time and energy on the riverfront and our riverfront park … instead of light rail and (the) Plaza.”

CASE NO. 2: CORRIGAN STATION

On the horizon, another Port KC abatement deal that concerns Williford and others is a 20-year, 100 percent exemption for Corrigan Station, an office building under construction at 1828 Walnut, a block off the streetcar line.

It saves developers some $2.2 million.

Current taxes on the unimproved building are $132,000 a year.

Without the abatement those taxes would continue to be divided among the various taxing jurisdictions including City Hall, the Kansas City School District, Metropolitan Junior College, the Blind Pension and others.

But the city has agreed to forego its share of those taxes, about $21,000 a year, or more than $400,000 over the life of the deal.

After the city reduction, the developers will pay $111,000 annually on a building that, after improvements, would fetch much more in taxes.

Overall, the developers will benefit from a total of about $16 million in publicly funded subsidies at Corrigan Station. Those include historic tax credits and funding from the city.

Port KC’s Collins says it’s worth it because the project is expected to generate 662 office jobs with an average annual salary of $55,000.

But promised jobs from abated properties don’t always materialize, and Williford said he’s still not convinced the abatements were needed.

He points out, for example, that the projects at 20th and Main and the Corrigan building are on or near the new light rail line.

After all, Williford said, light rail was supposed to enhance property values along the streetcar route.

“I support the streetcar,” Williford said. “I think it’s going to be a huge economic driver. …But the streetcar in and of itself is enough of an economic incentive that they can stop giving away the money of the library and the school district.”

Sure, Collins said, the light rail line will “enhance the opportunity for development.” But he added that values do not go up immediately and critical gaps remain between project costs and estimated revenues.

At this point, Collins said, he’s tired of being a lightning rod for criticism of abatements, especially downtown.

He doesn’t want to do any more abatements in the central business district, Collins said. “I’m tired of the (media) interviews,” he said, adding that Port KC has more important things to do with its time.

This story is part of a reporting collaboration between KCUR and KCPT’s Hale Center for Journalism exploring the economics behind Missouri River navigation and Port KC development. See the first story in the series, from KCUR’s Suzanne Hogan, here on Flatland.

Illustration by Coleman Stampley for Flatland.