Missouri Ponders the Power of the People How Missourians Push Political Change Without the Legislature

Published September 15th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: A volunteer for Legal Missouri proudly holds up a collection of ballot initiative signatures. (Courtesy | Legal Missouri)Here’s what it takes for average citizens to change public policy in Missouri.

It takes about an hour of standing outside in all weather conditions and talking to strangers for one person to gather eight to 10 signatures.

About 30,000 hours of the signature gathering must take place across the state to ensure a ballot initiative can be put before Missouri voters.

That’s what it takes for dedicated volunteers and campaign leaders to bypass the Missouri legislature and push issues they find important.

For some, that’s a small price to pay to practice direct democracy.

“The ballot initiative process is our right. It’s something that we have the ability to actually make an impact,” said Nomachot Adiang, who worked on the Medicaid expansion ballot initiative in 2020.

The initiative petition process has been how many issues have found their way into Missouri law. In recent years, Missourians have approved Medicaid expansion, medical marijuana and increased the minimum wage through the process. It is how the legalization of recreational marijuana got on this November’s ballot.

In the wake of recent successes at the polls, those who use ballot initiatives increasingly fear the legislature will restrict the process. Those opposed to the issues pushed forward by the process think its users have too much power.

Indeed, the ballot initiative process has become the most elemental of political issues – a battle over who runs Missouri.

Flatland on YouTube: The People’s Power

What is a Ballot Initiative?

Missouri voted to have an initiative petition and referendum process in the first decade of the 20th century.

It wasn’t until 1920, however, that the first ballot initiative passed. It called for a rewrite of the state’s constitution. Since its creation, Missourians have voted on more than 100 ballot initiatives.

Missourians can petition to amend the state constitution and to amend state statutes, which is a power afforded to citizens in about half of the states in the country.

Those on the ground collecting signatures and writing the initiative proposals find the process expensive and labor intensive.

Backers of Medicaid expansion raised more than $10 million to finance the campaign. The recent ballot push for adult-use marijuana legalization had an almost $6 million campaign. The money went to attorneys and advisors while drafting the language, and travel and payments to signature collectors. Moreover, both campaigns faced significant hardships because the COVID-19 pandemic increased the cost.

While difficult, Adiang explained the ballot initiative process was the only way to get Medicaid expansion passed in the state, and more importantly, get folks access to much needed health care.

“Politics was getting in the way of good policy,” said Adiang, who noted that Missouri could have opted into Medicaid expansion nearly a decade sooner.

Her organization, Missouri Health Care for All, frequently talks with legislators and shares their stories. While legislators are good listeners, Adiang said it doesn’t guarantee their actions.

“We are grateful that there are representatives and senators that actually will listen to their constituents,” Adiang said. “But they’re individuals, we can’t control their behavior … There are people that will say they’re going to do something, and they don’t do it.”

A signature to put an issue on the ballot allows Missourians to directly act on the things they want to support, Adiang said. If it makes it to the ballot, each vote counts.

“That’s very different than having to wait to see if someone that you voted for, or maybe even didn’t vote for, is going to honor (your issue),” Adiang said.

Control Issues

Recent ballot initiatives, in Missouri and other parts of the country, have pushed progressive policies in states that have conservative majorities in the legislature.

Peverill Squire, a professor of political science at the University of Missouri, said while this is the current trend, it was the reverse 50 years ago.

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the ballot initiative process was popular with conservatives who wanted to push issues in liberal states.

“Over the last decade, decade and a half, when conservatives have enjoyed greater strength at the state legislative level, it’s liberals who have now rediscovered the utility of the initiative process and have pushed legislatures … to either adopt measures that are a little more liberal than they would like, or to simply bypass a legislature and adopt measures through the initiative process,” Squire said.

Some Missouri legislators this year sponsored a bill to make it more difficult to put an issue on the ballot.

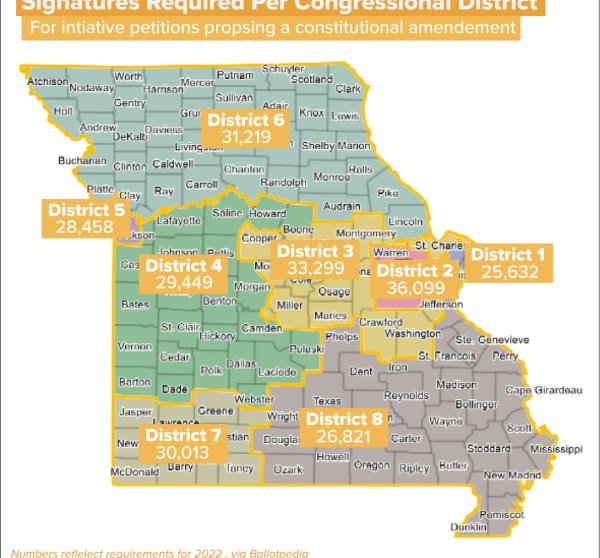

House Joint Resolution 79 (HJR79) sought to increase the threshold required for approval from a simple majority to a two-thirds majority and to increase the percentage of signatures required in each congressional district from 8% (for constitutional amendments) to 10% of the gubernatorial voter turnout.

HJR 79 passed the House and was placed on the informal Senate calendar for the upcoming session. To take effect, however, it would have to be approved by Missouri voters.

Its sponsor, Rep. Mike Henderson, did not respond to interview requests.

Similar bills have emerged in the past couple of years attempting to further curtail the process, arguing that it is too easy to get an issue on the ballot to amend the constitution.

In Squire’s opinion, these efforts have been entirely motivated by politics.

“You have conservative Republicans who are reacting to the fact that liberal Democrats have been successful at the ballot box over the last 10 years, forgetting that it was conservatives who used that same device to get their measures put into place in the previous couple of decades,” Squire said.

Some states with looser requirements end up with lots of initiatives on the ballot, which can be overwhelming to voters. Squire said that is not the case with Missouri, which only ends up with a handful of initiatives on the ballot.

“It’s more (about) trying to make it more difficult for people pushing policies they don’t like to get those measures put before the voters,” Squire said.

Advocates and activists who see the ballot initiative as the only way to help their communities fear they will lose their right to direct democracy in the state.

Justice Gatson, founder of Reale Justice Network, has worked on several ballot initiatives in the past, and is working towards a ballot initiative that would give Missourians the right to abortion.

The Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in June left little time for activists like Gatson to gather signatures and start an initiative petition in time for the upcoming election. But time is of the essence, and Gatson is already in the works planning and gathering a team to put abortion on the ballot for the next general election.

Not only are the folks she works with hurting, but she fears a future where the process doesn’t exist or has regulations that make it too difficult to get anything approved.

“We need to do this and we need to do it quickly. We need to do it before rules change,” Gatson said. “We need to hold on to every single piece of power that we have, and our initiative process is it.”

In addition to the legislative efforts threatening the process, proponents like Gatson have seen other states lose their ability to initiate petitions.

After approving several ballot initiatives in 2020, Mississippi’s Supreme Court ruled the process unconstitutional. Idaho severely restricted its process last year with a new law. Squire said in Illinois it’s incredibly difficult to get an issue on the ballot anymore.

“It’s hard to argue this sometimes, but I think Missouri may in fact have the right balance,” Squire said. “We have something the voters can handle and then when there’s enough support, the ability to get things on the ballot.”

Adiang found the process of putting Medicaid expansion on Missouri’s ballot in 2020 arduous, but she agrees that Missouri has a good balance.

“There is a level of difficulty, and for good reason, there should be some difficulty, but it’s something that definitely should not change,” Adiang said. “I think the way that it’s structured right now is the … optimal level of difficulty.”

Without making the process more difficult, there are still ways to oppose a ballot initiative.

When Missouri voters passed an amendment to expand Medicaid in 2020, Adiang had feelings of relief and euphoria knowing that her cousin and thousands of other Missourians would have access to the care they needed.

But that feeling faded quickly.

Early in 2021, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson announced Medicaid expansion couldn’t happen as scheduled in the amendment, because it didn’t create funding for the program, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“To find out that … they were not going to honor our decision, disappointed isn’t even the right word,” Adiang said. “I remember I think I felt I was at a loss (like), ‘I don’t know, what are we supposed to do?’

“There’s a lot of ways that we have things in common. But I think sometimes politics really does get in the way of us addressing issues that we all collectively deal with.”

Those who fought for the ballot amendment pushed back and filed a lawsuit against the Department of Social Services. In July of 2021, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that the ballot initiative was indeed constitutional, and several months later, the program could begin enrolling patients.

All Politics

While it might seem like it, Squire said the popularity of recent ballot initiatives doesn’t reveal much about voters’ faith in their elected officials.

Legislators tend to push different issues than what citizens do through a ballot initiative, but legislators were still voted into power by the people.

“It tells us that voters like being able to make decisions directly themselves,” Squire said.

Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft said the United States was founded as a constitutional republic to ensure everyone’s voice was heard, not just the majority’s.

“Our country is not perfect, but at least in an aspirational sense, our country tried to be founded on the idea, tried, that we would have the idea of minority rights with majority rule,” Ashcroft said.

That’s to say if all laws were passed in the way a ballot initiative is, it would only be majority rules. The voice that disagrees wouldn’t have a say, or a constitutional right to say something.

“I think we need to be careful to make sure that we have an avenue for the people to make sure their voices are heard,” Ashcroft said.

Ashcroft believes in the ballot initiative process. But he doesn’t feel every issue should be a constitutional amendment.

For example, he said some ballot initiatives in 2018 passed with approval from about 13% of registered voters because of poor turnout.

“I think that if you’re going to put it in our constitution, it ought to have real broad breadth of agreement with the people of the state,” he said. “I know politics is a little disjointed these days, but I think there are some things that we can find broad agreement from.”

Ashcroft said he doesn’t want it to be harder to get something on the ballot, but thinks that rather than a simple majority, Missouri should opt for a “maybe 60%” majority.

“I like the idea of it being hard enough that the people that are in favor of it feel like they need to run a real campaign, and the people that are against it feel like that if they run a good campaign, they can defeat it,” Ashcroft said. “I think it’s healthy to have a discussion about how (to) do that.”

For it all to work the way it should, folks need to be more politically engaged.

“I wish we could get more people to participate in … normal elections, as opposed to statewide issues,” he said. “ I think it’s tragic, the voter turnout rates we have for school board elections and municipal elections.”

Part of that participation can also appear in the ballot initiative process.

The Secretary of State’s office accepts public comments on all of the initiatives it fields. Missourians can visit the office’s website to read the initiatives that are filed and to voice their opinions. Those comments help inform the office which parts of the constitutional change are most important to Missourians, or which parts are confusing.

“It’s unfortunate that more Missourians aren’t involved in that because when we’re changing the constitution that’s not a you-can-follow-it-or-not, that is the law,” Ashcroft said.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Cody Boston is a video producer for Kansas City PBS. This story is part of ongoing midterm election coverage by members of the KC Media Collective.