Treatment, Grief — and Insurance A Family Fights Through the Practicalities of Mental Health Parity Laws

Published June 4th, 2018 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Lizzy Huffman, left, and her mother, Jenny, are still working to get Lizzy into the appropriate level of care for her eating disorder. (Catherine Wheeler | Flatland)Lizzy Huffman was 5 years old when she first began to consider herself overweight.

It would take nearly a decade before practitioners officially diagnosed her with a multifaceted eating disorder that combines elements of bulimia and anorexia. That was two years ago, and the Lenexa woman is now 18 years old.

But for Lizzy and her mother, Jenny, insurance battles have been almost as exhausting as fighting the eating disorder itself.

Although regulators ultimately found the Huffmans’ insurer to be in compliance with state law, their experience highlights how one of the mental health community’s most significant victories of the past couple of decades has failed to fully live up to the expectations of its supporters.

But on a more personal level, Lizzy’s story is also about how her father’s own health issues impeded the teen’s recovery and strained the loving, yet complicated, relationship between the two.

“For me, it’s been terrifying because I don’t know where I am in my treatment,” Lizzy said.

Equal Treatment Under the Law

One long-running complaint from the mental health community was that that insurers scrimped on psychological coverage when compared to coverage for physical ailments. That gave rise to the “mental health parity” movement, which ultimately succeeded in getting federal legislation passed in 1996.

Many states, including Missouri and Kansas, followed suit with companion legislation. Parity rules mostly apply to employer-sponsored group health plans that cover about half of all Americans through their jobs.

The Parity Leadership Coalition, an advocacy organization that includes the American Psychological Association, provides a comprehensive overview of state and federal policies.

The nut of the current problem is this: While progress has been made on the financial aspects of parity, like copays and deductibles, equal access has been tougher to come by, meaning mental health patients can face narrow provider networks, tough pre-authorization requirements and strict treatment protocols.

The latter two factors were at play in Lizzy’s case, especially when it came to her residential stays at the Laureate Eating Disorders Program in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Parity studies often focus on mental health as a whole, rather than specifically on eating disorders.

For instance, in a report issued last year, the National Alliance on Mental Illness found that roughly a quarter of respondents had trouble finding an appropriate residential facility for treatment.

A similar percentage of respondents reported having to go out of network to receive residential care, and that’s a problem because going out of network is typically more expensive for the patient because the provider has not negotiated an agreed upon price with the insurer.

New Directions is a Kansas City, Missouri-based behavioral health management company, and it is significant player in our region because it works with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas and Blue KC.

It manages the HMO provider for Blue KC. New Directions said its Blue KC network meets and exceeds standards of network adequacy. If a Blue KC consumer is struggling to find a provider in-network, New Directions can use single-case agreements with providers who are out-of-network in certain cases.

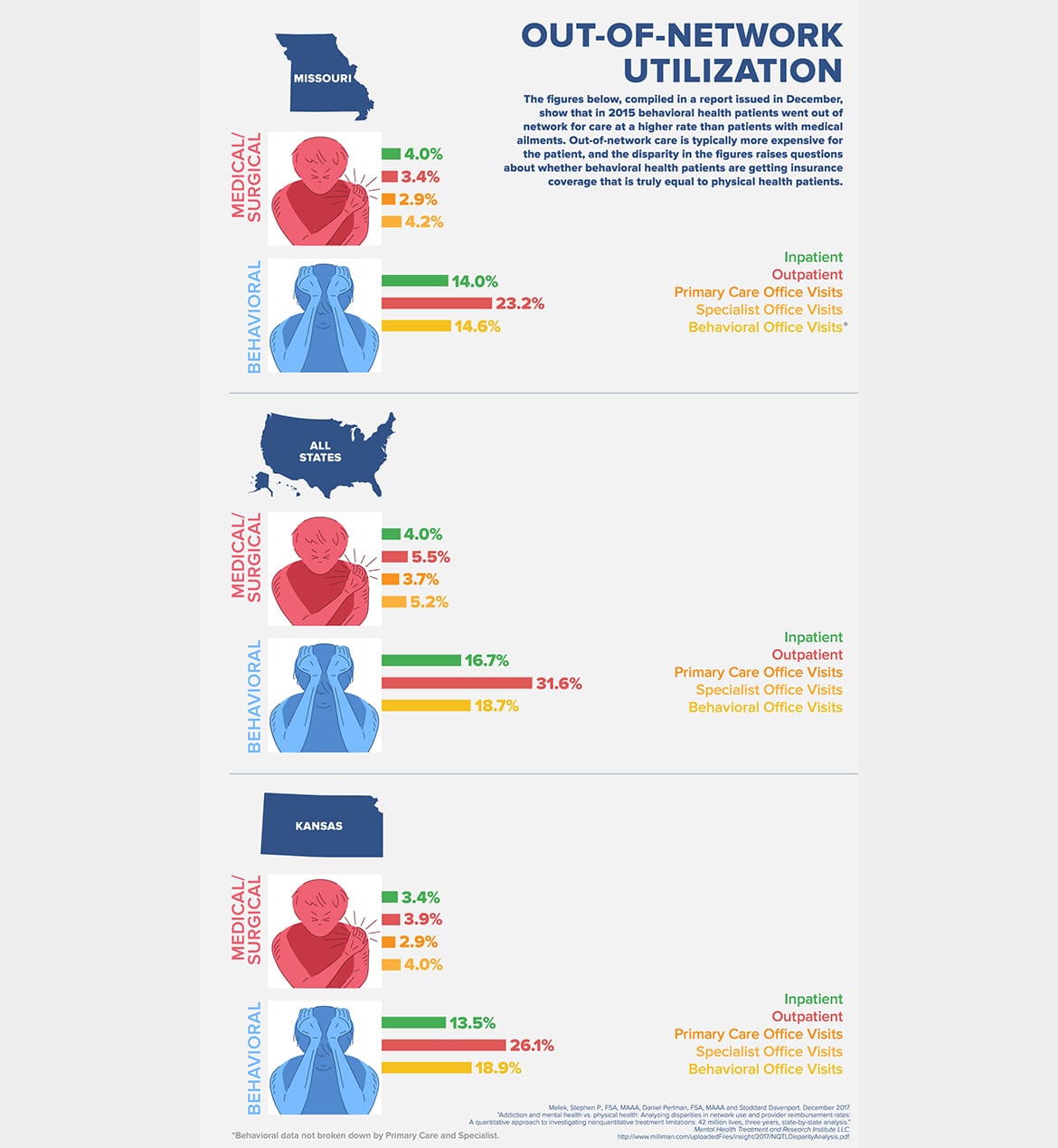

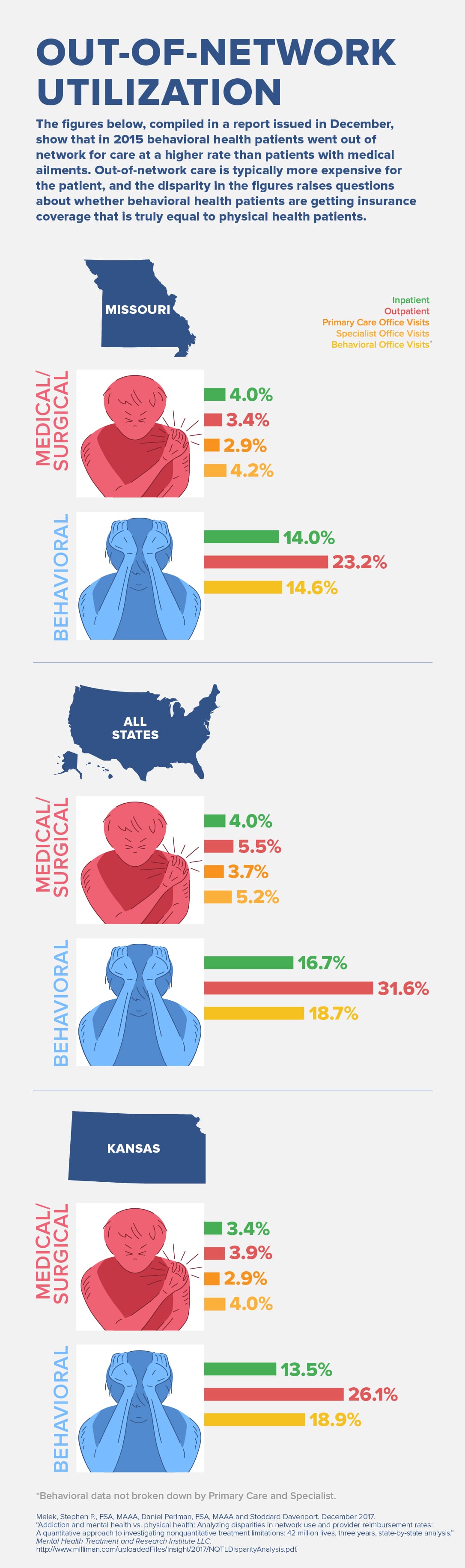

Milliman, an international actuarial firm, issued a report in December that highlighted out-of-network discrepancies between physical and behavioral health care. The findings were based on private health insurance data from 2013 to 2015. Data from the most recent year studied are presented in the graphic below.

Beyond being more expensive, out-of-network care is also a problem for consumers because insurance companies tend to cover less of the costs, said Steve Melek, one of the authors of the Milliman report.

“You could say network use is a proxy for network adequacy,” Melek said. “If people are going out of network so much, you might wonder if there is a network adequacy problem.”

It can also be difficult to find a mental health practitioner that specializes in eating disorders, especially in rural areas.

Residential care, like the kind provided at Laureate, tends to be one of the most intensive — and expensive — forms of treatment. It is reserved for patients who are seriously ill both mentally and physically.

There is no residential eating disorder treatment facility in the Kansas City area. The closest ones, besides Laureate, are in Denver, St. Louis and Chicago.

This scarcity of residential care illustrates the failure of parity on a couple of different levels, both of which are tied to the issue of intense scrutiny of care by insurance companies, according to people working in the field.

For one, the complexity of eating disorders tends to make them expensive to treat, which means insurance companies want to manage costs as much as possible. Secondly, residential care is one of the most expensive treatment options, so insurance companies have an incentive to be very cautious about authorizing this level of care.

New Directions said it cannot control that there are no residential eating disorder treatment facilities in the area, but the company refers Blue KC consumers to a residential treatment facility in St. Louis frequently through single-case agreements. There are facilities in the Kansas City area that offer other levels of care for eating disorder treatment.

Kathryn Pieper, director of the Children’s Mercy Eating Disorders Center, said treating patients with eating disorders at a lower level of care than they need could cause their recovery to be longer, and therefore more expensive in the long run.

New Directions declined to discuss Lizzy’s case specifically because the company does not typically comment on individual cases.

The company said that cost is not a consideration when determining medical necessity for consumers’ requests for a particular level of care.

“The only considerations from New Directions’ perspective are: 1) does the member have the benefit for the service they are requesting, and 2) does the service request meet the medical necessity criteria,” the email response said.

Lizzy and Ron

By August 2016, Lizzy was ready for another stab at Laureate. In her first stint, a few months before that, she had not been ready to admit she had a problem.

But her 44 days in treatment were tinged with the knowledge that her father, Ron, was sick with something. But he would not see a doctor until Lizzy returned from Oklahoma.

The father and daughter had a tight bond, roaming around the city while they were running errands. They laughed a lot on weekend trips to the family farm, where he would mow the grass while she sat in the pasture drawing.

One weekend Lizzy’s parents came to Laureate for a visit, and Ron began burping at dinner. Lizzy and her mother were mortified. “You don’t burp at the table in an eating disorder hospital,” Lizzy said.

As they found out later, that was a symptom of his esophageal cancer.

The family had planned for a strict recovery schedule once Lizzy returned from Laureate. But Ron’s illness changed that.

Ron feared that, if Lizzy went off to get more treatment, she wouldn’t be there if he died.

“For him this was it,” Jenny said. “And do we want to take Lizzy away from him during their precious time?”

So Lizzy stayed in Lenexa, getting as much counseling as she could without leaving. It was rough because Ron relied so heavily on his daughter.

“I was the one he wanted to put a lot of things on,” she said. “He would always say he wanted me to take care of him.”

One evening, while Jenny was out running errands for Ron, Lizzy sat with her dad in his room. She took a picture of her holding her father’s hand. That’s when she noticed his pulse was irregular. Then, he stopped breathing.

Lizzy did chest compressions while first responders were on their way. She thought she didn’t have the power to do it, but for three minutes she did. She tried as best she could to bring him back. But she knew he was gone.

She realized that her father had passed away, and she couldn’t save him.

Ron was a physician, and he was always concerned about his daughter’s weight. He didn’t want her to have diabetes. That was ironic, since Ron was overweight himself.

Nevertheless, she put a lot of pressure on herself to be the healthy, thin daughter of a doctor. And it was hard for her father to grasp that her problem wasn’t physical, but mental.

Because treatment is expensive, eating disorder specialists argue, insurers often judge progress merely by seeing whether the patient has reached a healthy weight.

“That is looking at recovery in a simplistic manner,” said Pieper, the Children’s Mercy director. “There still could be a lot of problematic behaviors or psychological or psychiatric fragility.”

Yet New Directions said weight is only one of many medical and behavioral factors it uses in making care decisions. The company said it uses weight as a medical factor only as it is consistent with criteria set out in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

Requests for residential treatment coverage are handled the same way as requests for other services. If necessary, a New Directions psychiatrist will work with the consumer’s provider to determine whether the request meets medical necessity criteria. If the consumer does not like the outcome, they are provided with the information for an appeals process.

Lizzy thinks this focus on weight has complicated her treatment, because as someone who is not underweight, she tends to physically stabilize quicker than other patients.

She said that once, when she was at Laureate, the doctor sat all the patients down and said they had to get their blood pressure checked three times a day or insurance would send them home.

“I think insurance does good job of saying, ‘Yes, this person who is underweight qualifies for this.’ But it’s a lot harder to justify to appear to be at a normal weight but their behaviors are dangerous,” said Emily Reilly, a clinical social worker at the Children’s Mercy Eating Disorders Center. Reilly works with treatment providers and families to find the best place for a patient to recover.

New Directions said its goal is to ensure its members receive appropriate care by using medical and scientific-based standards to help each member achieve the highest level of functioning possible.

Missouri Sets Example

In January 2017, eating disorder advocates in Missouri celebrated a victory that was eight years in the making — when the state implemented one of the most aggressive state parity laws aimed specifically at eating disorders.

The new regulations forbid insurance companies from using weight as the sole contributing factor when determining coverage eligibility.

The law requires insurance plans to cover all medically necessary treatment. It also sets out clear standards of care by defining treatment at every level — from inpatient to outpatient — and uses eating disorder definitions from the APA diagnostic manual.

Paul T. Graham was instrumental in drafting the legislation. He came to the issue as a private-practice attorney in Jefferson City who had represented clients fighting insurance companies over eating disorder treatment decisions.

Graham said the law is a significant improvement for patients with eating disorders. Most importantly, he said, the clear-cut standards now set out in the regulations mean patients should not have to justify their treatment needs at every turn.

Because of the law, the focus for families can now be on recovery and healing rather than on fighting for coverage for care, said Annie Seal, an advocate who also played a key role in getting the law passed.

New Directions said it recognizes and adheres to the law.

Measuring Parity

The Huffmans’ problems centered on coverage for residential care.

Their complaint to the Kansas Insurance Department argued that their policy was not parity compliant because it did not cover residential care for mental health. The insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas, argued that the policy complied with state law because residential care was not offered for either medical/surgical or mental health.

The insurance department determined the policy complied with state law.

Insurance did partially pay for the portion of Lizzy’s residential care that it considered to be outpatient care, but that left the Huffmans on the hook for overnight care at the facility.

In Missouri and Kansas, the state insurance departments investigate complaints to see whether companies are complying with state law and with the provisions of their own policies. In both states, once the complaint is filed, the insurance department works with the parties and may request additional information.

Regulators in Missouri and Kansas said complaints are often the way the departments find out how policies they have approved are being applied with consumers. Though if consumers don’t know they can make complaints, they said, it’s hard to gauge whether there are problems with the application of policies.

Making It Better

Mental health advocates and insurance-reform proponents list several ways to improve the system.

One way is gaining a better understanding of the issue, said Melek, the author of the Milliman report.

One more step in studying possible discrepancies in network adequacy, he said, would be to compare the actual number of in-network behavioral health providers with the number of in-network providers of medical and surgical services and specialty services.

The analysis, he said, would also take into account the numbers of providers in each practice type that were taking new patients. The comparisons would be based on provider-patient ratios to account for varying sizes of patient groups.

The question, he said, is this: “Are you discriminating against people with mental health or substance use disorders by not having as adequate of a network, which makes them have to go out of network for the services they need, and now it’s much more expensive for them?”

Melek also said state insurance departments could strengthen their policies, in part by ensuring parity compliance on the front end when insurance companies file their policies for review. That could include having actuaries review the filings.

He also suggested that insurance departments perform random field audits to ensure that the companies are complying with their own policies and with state law.

New Directions said it evolves its practices and policies as the law and understanding of parity also evolves.

This means keeping up with industry best practices and parity compliance tools. If New Directions identifies any problems with compliance, it works to make adjustments to operations or, if necessary, adjusts the health plan’s design.

Ron Honberg, the senior policy adviser for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said that it will likely take a holistic approach at the state and federal levels to address the problems of mental health parity, especially in enforcing it.

“Strong enforcement is most likely to occur at the state level,” Honberg said. This could mean attorneys general setting mental health as a priority or insurance commissioners getting more aggressive in their oversight.

That involves educating insurance consumers on what the laws mean, where to file complaints and what qualifies for a complaint, Honberg said.

“Achieving true parity is an elusive thing,” Honberg said.

—Wheeler produced this story as part of her graduate work at the Missouri School of Journalism. She earned her master’s degree from the school in May.