KU Doctor Wins Big Grant to Pursue New Alzheimer’s Theory Dr. Russell Swerdlow Posits New Theory on Cause and Treatment of Alzheimer’s

Published August 31st, 2022 at 10:00 AM

Above image credit: Dr. Russell Swerdlow, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Kansas, is one of 10 scientists announced as winners of the Oskar Fischer Prize. (Courtesy | University of Kansas Medical Center)A local physician who has spent decades pursuing an alternative theory for the cause of Alzheimer’s has gotten crucial affirmation — a chunk of the $4 million Oskar Fischer Prize.

Dr. Russell Swerdlow, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Kansas, is one of 10 scientists announced as winners of the Fischer Prize in June. The award is meant to help researchers “look beyond prevailing theories and direct future research” into Alzheimer’s disease.

Since it was first recognized more than a century ago, research, and billions of dollars, have concentrated on one main factor that could be contributing to Alzheimer’s – amyloid plaque. But this focus has generated little advancement in understanding, treatment or cures of a disease that affects more than six million Americans.

Swerdlow, who was awarded $300,000, is hoping to move Alzheimer’s research in a direction he’s been studying since the 1980s. He has long posited that mitochondria are at the heart, and cause, of Alzheimer’s disease. Mitochondria are membrane-bound parts of cells that generate most of the chemical energy needed to power cells’ biochemical reactions.

“That’s the reason why this prize is so important,” Swerdlow said. “If you want to sell your hypothesis, you have to convince people, and this is a sign we are doing that. Also, when people start to endorse your ideas, it makes others think, ‘Maybe there is something to this.’ ”

Prevailing Alzheimer’s Theory

No one knows what causes Alzheimer’s disease. But years of research suggests genetics, the environment (air pollution and exposure to heavy metals), lifestyle (social engagement, sleep, exercise), health (presence of heart disease, high blood pressure, obesity) and aging-related changes to the brain are contributing factors.

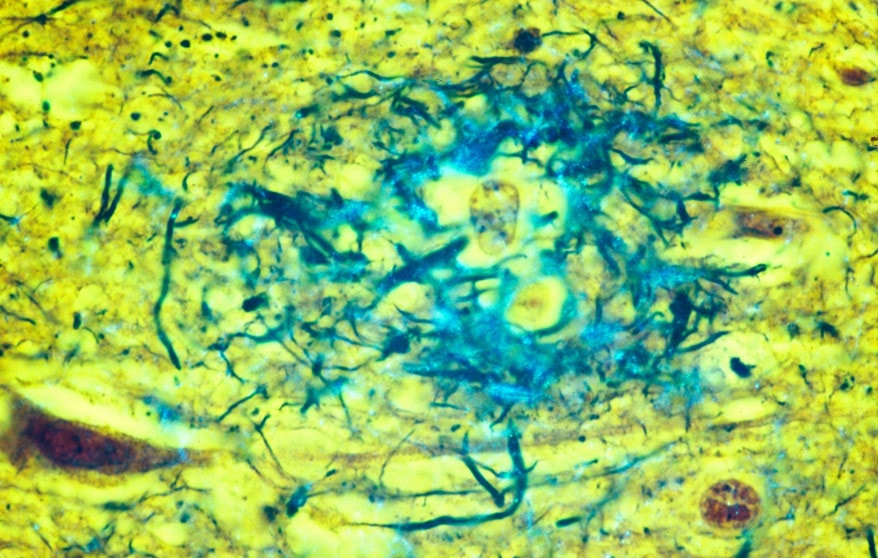

These factors are thought to create changes that occur in the brain. A buildup of beta-amyloid proteins results in plaque that accumulates between the brain’s nerves. Another suspect is the protein tau, which can tangle and interrupt delivery of nutrients to brain cells. Plaque and tangles are thought to slowly starve the brain, cause inflammation, and destroy the synapses that move signals between cells.

Plaques were found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients in the early 1900s. The amyloid cascade hypothesis was first named in the journal Science in 1992 as the cause of Alzheimer’s.

Today, nearly every health organization ranging from the National Institute on Aging to the Alzheimer’s Association point to these factors as the known cause of the disease. And for more than three decades most of the research and funding in the Alzheimer’s space has targeted these proteins.

According to Swerdlow, it was in the mid-1990s that scientists were able to create mice that developed amyloid plaques. This enabled researchers to use mice to study Alzheimer’s. And it required that researchers assume that amyloid was causing the condition. Data that came from these studies supported that theory.

“It was a snowball that rolled down the mountain and picked up traction,” he said. “Investigators and drug companies got behind it and drug manufacturers tried to find ways to keep amyloid from accumulating.”

That may still be the main theory. But as the data accumulated over the years, the evidence that amyloid causes Alzheimer’s is “less robust,” he said.

“In 2022, we can keep amyloid from forming and can remove it reasonably well when it has formed,” Swerdlow said. “But most of these interventions don’t make people better. Ongoing clinical trials focusing on removing amyloid are only more likely to inform us on the question of how toxic amyloid is in the brain of humans.”

No other single hypothesis has supplanted the amyloid theory to date. Although amyloid is a major component of the disease, Swerdlow believes that it is a byproduct, rather than a cause. And Swerdlow, also a professor of neurology at KU Medical Center, said other targets, like mitochondria, are gaining research momentum.

History of a Hypothesis

Swerdlow was in high school in the 1980s when his grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. That impacted his development and crystallized a couple of things for him. First, Alzheimer’s was a terrible condition. Second, treatment had to be found.

At the time, he was already interested in neurology. When he went to college, his focus expanded to neuroscience and biochemistry.

As an undergraduate at New York University, Swerdlow became involved in memory research in the psychology department. The summer before he entered medical school he was stuck in Manhattan and wanted a job. Although summer research positions were supposed to be for medical students, he landed work with investigators analyzing PET scans of Alzheimer’s patients to determine how well their brains used sugar. They found Alzheimer’s brains were not processing sugar efficiently, and effectively starving the brain.

Swerdlow graduated from NYU’s medical school in 1991 and moved to the University of Virginia for neurology training. It was there that he met faculty who thought mitochondria might play a role in the condition. He continued this study as a resident, and it evolved into the focus of his career.

There are a several reasons why Swerdlow believes there’s a good case that mitochondria may be a cause of Alzheimer’s:

- The brains of people with Alzheimer’s show misshapen mitochondria.

- Some patients with Alzheimer’s have less mitochondrial brain activity.

- The Alzheimer’s brain is less efficient at using glucose for energy.

- Some people who develop plaques and tangles don’t develop Alzheimer’s.

- And mitochondria, not amyloid, is associated with aging – a major risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s.

Swerdlow named his theory the “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis.” In essence, his focus is on energy metabolism, or the processes and pathways that cells and tissues use to create the energy needed to survive.

“It’s the spark of life we need to combat entropy, and without it, life isn’t possible,” Swerdlow said. “Cells have multiple ways to make it and at the heart of that is mitochondria. If mitochondria go bad, then really most of the energy metabolism pathways go bad.”

It is when mitochondria begin to go bad that triggers poor energy metabolism, which, in turn, causes Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

Living organisms need energy to maintain the structure of its molecules. If that energy is compromised, the components maintaining that structure changes. There’s a very delicate balance in cells and if that balance is thrown off, “the wheels can come off the wagon,” he said.

He admits there could be several factors above and beyond changes in mitochondria. These organelles — specialized structures that perform various jobs inside cells — could even be a small part of the overall picture.

“But it’s like pick-up sticks,” he said. “You may be able to remove a lot of different sticks without disrupting everything, but there is always one that you pull on and everything just collapses. If mitochondria are damaged leading to a difference in the status of energy metabolism, it may be the crucial stick that throws everything else out of whack.”

Over the years, Swerdlow has worked to answer three main questions:

- Why does energy metabolism break down in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s?

- What are the consequences of failed energy metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease?

- And can energy metabolism be manipulated to treat Alzheimer’s?

Decade of Data

Swerdlow will be the first to concede that his work is nowhere near complete. A hypothesis, by definition, is an educated guess. The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis took more than a decade of work to name and then decades of work to progress.

“We haven’t proven the hypothesis,” he said. “We have a long way to go but have made a good case as to why it is a viable hypothesis and deserves to be studied.”

Over the years, Swerdlow has generated data that supports his conclusion. First, he said that mitochondrial changes occur both in the brain and in blood, skin and muscle cells as people age. That proves that it’s not just an Alzheimer’s brain’s toxic environment that causes mitochondria to be altered. The mitochondria may be the precursor to future damage.

He also said he had to tie genetics to his theory. He needed to show that the genes that help regulate mitochondrial functioning affect Alzheimer’s disease. There’s no “slam dunk” there, but he said they have made some headway on that front.

Mitochondrial damage also needed to be shown as a cause of plaques and tangles, which are the classic change in an Alzheimer’s brain. It has been established that mitochondrial function can impact plaques and tangles in the brain. He called research in this space provocative, but it’s been difficult to prove that mitochondria is the factor causing the plaques and tangles. Research in this space has only been done on animal models, not humans.

Swerdlow said he’s also been able to show that manipulating mitochondria and energy metabolism has a positive impact on patients. He has performed research showing that lifestyle interventions like dietary changes — ketogenic diets, in particular — can improve memory in some patients.

“We are at a place where the amyloid people were about 20 years ago,” he said. “Figuring out ways to move the needle and then determine if they have efficacy. We have established the needle can be moved, but it’s too early to address whether there is any efficacy in doing it.”

“If you want to sell your hypothesis, you have to convince people, and this is a sign we are doing that. Also, when people start to endorse your ideas, it makes others think, ‘Maybe there is something to this.’ ”

Dr. Russell Swerdlow, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Kansas.

A major component of mitochondria’s role in Alzheimer’s for Swerdlow is the fact that the risk of the disease increases dramatically as people age. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, 73% of the more than six million Americans with the condition are age 75 and older.

“I think any viable theory of Alzheimer’s disease is going to have to take brain aging into account,” he said. “For a long time, we have accepted that mitochondria make an important contribution to aging.”

Getting older, Swerdlow said, involves a lot of compensation. If people can counterbalance the changes that occur in the body, they age well. It’s when the changes become too much to compensate for that problems arise — too many memories are lost, daily tasks become unmanageable and social activities too exhausting.

“We will cure Alzheimer’s disease when we cure brain aging,” he said. “And we are more likely to do that by manipulating mitochondria and energy metabolism than by pulling amyloid out of brains.

“The argument seems to have shifted to whether mitochondria are very important or of ultimate importance with the disease. And if that’s where the battle lines are at, I couldn’t be happier with that.”

Tammy Worth is a freelance journalist based in Blue Springs, Missouri.