Risks and Rewards of Playing High School Football Local History of a Sport Called Both 'Man-Building' and 'Boy-Killing'

Published September 6th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: By the mid-1930s Kansas City area high school football players, like these members of the William Chrisman High School football squad in Independence, competed while wearing helmets and protective padded apparel. (Courtesy | Jackson County Historical Society)The Southwest High School football quarterback, then playing defensive safety, closed on the opposing ball carrier and brought him down.

The tackler didn’t get up.

Approached by his teammates and his coach, he said he had no feeling in his right leg. Then the 16-year-old hobbled back to the team bench, dragging the leg, and lost consciousness.

After an announcement asking for any doctor in attendance went unanswered, a spectator drove the athlete, his mother and the coach to St. Luke’s Hospital three miles north on Wornall Road.

There, less than an hour after the injury, doctors pronounced the quarterback dead.

After an autopsy, a Kansas City coroner concluded the cause of death had been a rupture of the meningeal artery on the left side of the athlete’s brain, which likely produced the symptoms he had described.

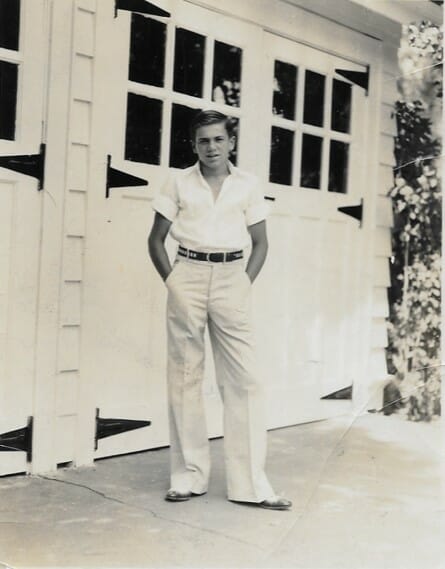

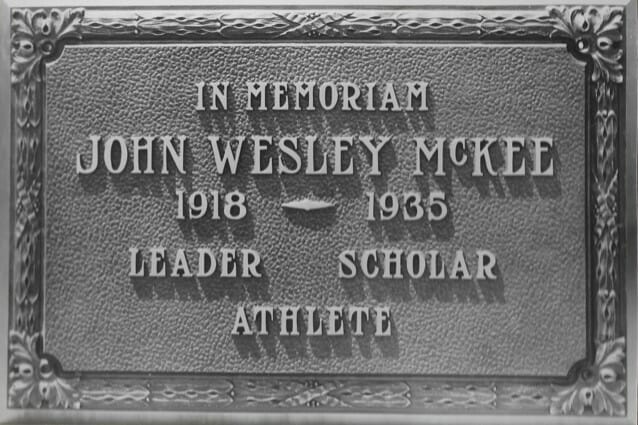

John McKee had been wearing protective headgear, the Kansas City Star reported, adding that the swiftness with which death arrived “was said to be rather unusual, indicative, perhaps, of the severeness of the contact.”

McKee’s Oct. 12, 1935, death stunned the estimated 300 Southwest High students gathered that night at St. Luke’s, members of the Kansas City Board of Education, and McKee’s family.

In the approximately 40-year history of organized Kansas City high school football, no one could remember anyone dying directly from a football injury.

The school board, five days later, heard testimony from a 17-member committee of educators, pastors and parents who advocated football not be abolished.

“We realize that there are risks in this great game, but we do not feel that they are any greater than otherwise in life so our unanimous opinion is — take all the precautions possible against accident but continue this man-building game,” the committee’s recommendation read.

The games resumed.

Over the subsequent decades, however, McKee family members were never allowed to try out for high school football.

Mark McKee, son of William R. McKee, Jr., the older brother of John, said that while the death remained a never-forgotten family tragedy, there was still a football in the house when he grew up.

“My father loved football,” McKee said recently.

A longtime mayor of Lee’s Summit, his father also had served a term as chair of the Jackson County Sports Authority and had enjoyed watching Kansas City Chiefs games in the authority’s Arrowhead Stadium suite, which adjoined the suite occupied by Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt.

Still, McKee said, he was not allowed to try out for football while attending Lee’s Summit High School in the 1960s.

Nor did he allow his own son, now 26, to do so.

“There is certainly a lot to worry about when raising kids,” McKee said. “To not have to worry about my son being injured on a football field?

“That’s a small victory.”

The Most Popular Sport

Kansas City area high school football has begun, continuing an autumn tradition that has continued — with one notable exception — for some 125 years.

In that time the game has grown more professionally administered, with coaches and educators assisted by sophisticated emergency response plans.

Unlike during the 1935 tragedy at Southwest High, medical professionals today routinely monitor area games, with ambulance crews — if not stationed onsite — trained in rapid response.

Some sports administrators maintain high school football has never been safer.

The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), an Indianapolis organization founded in 1920, asserted in a 2019 article “the risk of serious or catastrophic injuries has never been lower in the history of high school football.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the organization documented an average of 20 direct football-related fatalities every year — 35 athletes died just in 1970.

That number has decreased.

In 2021 four high school football players died during football-related activities, according to the annual survey distributed by the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, founded in 1982 and based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Meanwhile, football remains the most popular high school sport.

The NFHS in January reported that, during the 2021-2022 school year, 976,886 students played 11-member high school football.

That number, however, also was the first time since the turn of the 21st century that fewer than 1 million high school athletes played.

The number represented a 12.2% decline from a 2008-2009 high.

Over the years, risk has remained.

Examples of Kansas City area traumatic high school football injuries include:

- In 1983, playing for Bishop Miege High School’s sophomore team, Jeff Wicina suffered a cervical neck injury. Paralyzed from the chest down with limited use of his arms, he persevered, earning bachelor’s and graduate business degrees from the University of Kansas and working as a Kansas City financial analyst before his death, by suicide, in 1999.

- In 2010, playing for Spring Hill High School, Nathan Stiles died several hours after suffering a head injury during a game. In response, his parents established The Nathan Project, which has distributed an estimated 46,000 Bibles to youth centers across the region.

- In 2013, playing for Shawnee Mission West High School, Andre Maloney died after suffering a stroke during a game. He had committed to play at the University of Kansas.

- In 2014, James McGinnis, while playing for Olathe East High School, suffered a traumatic brain injury during a game. A doctor that night told his parents he could remain in a vegetative state.

But in the almost nine years since, McGinnis’ recovery has continued. He has appeared at several public events, once leading a 2K walk at an annual brain injury awareness run and taking part in ceremonies honoring area high school football players.

At such events he displays the American Sign Language hand gesture meaning “I Love You,” used in the McGinnis family since James was a third grader.

“It’s definitely been a life-changing experience, and there have been positive things that have come from it, seeing how people react to James,” Pat McGinnis, James’ father, said recently.

“But I would not wish it on anybody.”

‘Boy-killing Sport’

The Kansas City educators who agreed football represented a “man-building” sport in 1935 felt differently from their counterparts of 30 years before, who agreed that it was, in fact, a “boy-killing” pastime.

In 1905, 19-year-old Homer Gibson, playing for Kansas City’s Manual High School, suffered a head injury during a game in Lincoln, Nebraska.

“He was carried unconscious from the field, bleeding from a cut on the head,” the Kansas City Times reported.

Doctors in Lincoln removed a blood clot from his brain. By the time Gibson received approval to travel back to Kansas City in mid-December, he remained paralyzed on one side of his body, could not speak clearly or eat solid foods

Kansas City area high school students had been playing organized football since the mid-1890s.

In those years, the mild injuries sustained by players prompted light seasonal humor in the news columns of the day.

“Yes, turkey will be dismembered today, to say nothing of the football players,” noted the Kansas City Journal on Thanksgiving Day, 1895.

But 10 years later the holiday mood had changed.

The Chicago Tribune, four days before Thanksgiving, in a front-page article, announced the “FOOTBALL YEAR’S DEATH HARVEST” numbered 19.

“Of those slaughtered to make a touchdown eleven were high school players and ten of the killed were immature boys of 17 and under,” the newspaper noted.

Three players of those 19 had died just on Nov. 25.

Days later, a 20th athlete died, and very close to home.

Robert Brown, 16, of Sedalia had died. Brown, according to the Sedalia Democrat, had been running with the ball when he was tackled, “falling on his back and neck, resulting in his body being paralyzed from the neck down.”

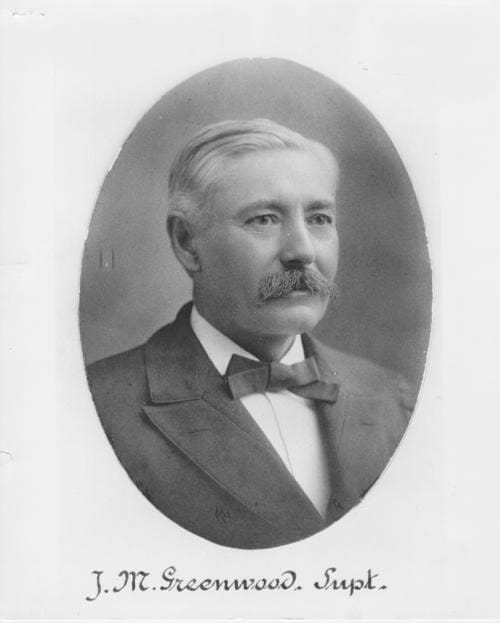

J.M. Greenwood, a Civil War veteran who would serve as Kansas City school superintendent from 1874 through 1913, soon presented a resolution to his educators.

“Resolved,” it read, “that football, as now played, is a boy-killing, an educational prostituting and gladiatorial sport that should not be tolerated in high or elementary schools.”

The resolution passed by a 38 to 8 vote.

Greenwood’s opinion of scholastic athletics would not improve over time.

“Professor Greenwood said recently he believed spelling bees would be a proper substitute for baseball and football and other athletic contests between the schools,” the Star reported in 1910.

Football in Kansas City high schools would not be sanctioned again until 1918.

Greenwood had died in 1914.

Three years later the United States had declared war on Germany.

President Woodrow Wilson, a longtime college football enthusiast, appointed football innovator Walter Camp as athletics advisor to the U.S. Navy.

Organized sports were considered part of the war effort.

“America’s coming victories in the cause of democracy and humanity can be attributed to the baseball diamond, the football field, the tennis court….” read an unsigned column in the Kansas City Star on July 4, 1917.

The following year Central, Northeast, Manual and Westport high schools resumed playing football, although the influenza epidemic prompted the cancellation of most of those games.

By then rule changes and equipment upgrades had made the game safer, its admirers believed, and over time its reputation would grow less disreputable.

In 1931 college football coaching legend Knute Rockne died when his plane, after taking off from Kansas City, crashed in rural Kansas.

In response Dominic M. Nigro, a Kansas City physician who had become a friend of Rockne’s while attending Notre Dame, established an annual award presented to the “most valuable” high school football player at an annual “Rockne Dinner.”

Nigro presented the award every year until his 1975 death.

In 1983 the family of Tommy Simone, a 12-year-old killed that year in an automobile accident, revived the annual honor.

In the years since more awards in several categories have been added. In 2011 the Simone awards ceremonies instituted the Nathan Stiles Inspiration Award, given to an athlete who “has made an impact on football in the Metro.”

The increased awareness of the risk of sports-related head injuries following his son’s 2010 death has been noticeable, his father said recently.

“I think Nathan is still the youngest documented case of CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy),” Ron Stiles said, referring to the degenerative disease sometimes found in athletes playing contact sports who suffer repeated hits to the head.

“I think there has been a new caution since Nathan’s death.”

Helicopter at Halftime

Just before halftime Nathan’s mother Connie noticed him walking in an unfamiliar, unsteady, gait near the Spring Hill High bench.

A moment later her cellphone rang — something was wrong.

By the time Ron and Connie got to the bench, their son had collapsed.

At halftime, a helicopter arrived to airlift Nathan to the University of Kansas Health System. Several hours later doctors told Nathan’s parents that while they had stopped the bleeding in their son’s brain, his heart and lungs were failing.

After several groups of Nathan’s friends, a few at a time, were allowed into his hospital room to say goodbye, his parents approved the removal of life support.

Nathan died at about 4 a.m.

An autopsy revealed Nathan had died from a “re-bleed” from an undetected subdural hematoma, perhaps suffered in a game played several weeks earlier.

Nathan had complained of headaches following a game in early October.

Doctors conducted a computerized tomography (CT) scan and cleared Nathan to play, and coaches held him out for some time as a precaution.

Soon after Nathan’s death, his father received a call from the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, and the family agreed to donate Nathan’s brain for research.

Doctors there discovered that Nathan’s brain, according to a 2012 CNN story, was “riddled” with tau proteins, often found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

One way the Stiles family responded is through the Nathan Project.

His parents have since helped distribute some 46,000 Bibles. Their son, they believed, had been reading the Bible the day he died.

“I was at a juvenile center yesterday with 18 kids and I’ve got three cases of Bibles I’m ready to hand off for a youth group south of Garnett,” Ron Stiles said recently.

“I know it has really helped me, seeing the impact this program has had with young people who are walking through some really tough times.”

Today Stiles would advise families of athletes to be alert to sudden changes in personality, one symptom of concussion, he said.

While that had not been the case with Nathan, since his son’s death Stiles has learned about similar cases from across the country. Such specific knowledge — plus the community caution that Stiles speaks of — is one positive outcome from Nathan’s tragedy.

“Like we said at Nathan’s celebration of life — if something needs to be learned from this, we want it to be by the doctors, and not the attorneys,” he said.

Inherent Risks

In July, a Kansas City, Kansas, federal judge approved a settlement with the mother of Tirrell Williams, 19, who died in 2021 from heat-related injuries suffered during a Fort Scott Community College preseason football training session.

In August, friends and family members of Myzelle Law, a 19-year-old MidAmerica Nazarene University football player, established a GoFundMe account to help with medical and funeral costs following Law’s July 30 death from what the account described as heat-related injuries.

Law had played football for Blue Valley North High School.

Mark McKee cannot remember any family discussion of litigation or settlements related to the 1935 death of his father’s younger brother, John.

Ron Stiles, meanwhile, said the insurance carried by Spring Hill High School was helpful following his son’s 2010 death.

“It basically covered the funeral expenses,” Stiles said. “The school was very good to us.”

Insurance carried by Olathe East High School has been crucial for the family of James McGinnis, who spent seven months at a Lincoln, Nebraska, rehabilitation center after suffering an acute subdural hematoma during a 2014 game.

Parents considering whether to let their teenagers play high school football would want to confirm the available insurance would cover rehabilitation expenses, McGinnis said.

“Rehab is very expensive and time-consuming,” McGinnis said. “The injury was impactful enough, but we did not have to worry about the finances.”

At the time of Jeff Wicina’s 1983 injury, Bishop Miege was one of the few schools in Kansas that did not carry a policy that would have helped fund rehabilitation expenses for life, according to stories published by the Star.

The school soon got such coverage after Wicina’s injury, the newspaper reported.

The Wicina family soon sued Bishop Miege and the Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas, alleging the school, in part, had been negligent in failing to provide such insurance.

At the time, as described in “After the Rain: A Mother’s Journey Into Hope,” published by Sandi Crupi-Wicina, Jeff’s mother and author of the 2021 book, she worked for the archdiocese as a family therapist at Catholic Social Services.

“I remember feeling scared inside as I told my husband, ‘We’re a family first,’” she wrote.

In 1987 the Kansas Supreme Court ruled against the Wicina family, affirming a lower court ruling the school had no duty to provide disability coverage.

“We feel sympathy for the severe injuries suffered by this plaintiff,” the court decision read.

“However, there are dangers and risks inherent in the game of football and those who play the game encounter these risks voluntarily.”

The family ultimately accepted a settlement, said Genon Wicina, Jeff’s sister and a Florida physician.

“That was the main reason for the lawsuit,” she said.

The settlement “allowed Jeff to get a college education and it also paid for a converted van and support people who helped him 24 hours a day, allowing him to live on his own.”

Purging ‘Platitudes‘

Crupi-Wicina’s book detailed what had happened to Jeff, who at age 15 was paralyzed from the chest down, with limited use his arms, following an injury sustained while playing for the Bishop Miege High School sophomore team.

But the book also documents her disappointment in the lack of accepted wisdom then available to parents in such previously unthinkable circumstances.

“I found story after story focused on the victim’s ordeal,” Crupi-Wicina wrote, “but not of how a parent, a mother, authenticates and moves beyond victimhood. With each book, I asked: ‘How does a mother exit pain once entered?’”

According to her book, on the afternoon of Nov. 3, 1983, the following things happened:

- She picked up the phone at her home to hear a Bishop Miege counselor say her son had been injured during that afternoon’s game. ”We don’t know the extent of his injuries,” she heard him say.

- She entered the emergency room of the Overland Park hospital to find her son on a gurney, still in his football uniform. Seeing his mother, Jeff moved his arms as if imitating a chicken wing flap. “Mom, this is all I can do,” he said. “Please, Mom, I don’t want to live this way.”

- A doctor, after examining x-rays, told Crupi-Wicina her son had suffered a cervical injury. “He is paralyzed,” the doctor said. “What movement he has now is most likely what he will have the rest of his life.”

- After administering a general anesthetic, doctors implanted cervical traction tongs into Jeff’s skull just above the ears to stabilize the site of the fracture and prevent further impingement upon the spinal canal. The doctors initiated 20 pounds of cervical traction, with the tongs weighed down with sand.

That was the first day of her son’s ordeal.

It also was the day Crupi-Wicina began writing her book, as a way to keep track of treatments received and options available, but also to honor her son’s personal resolve.

“We, as a family, worked really hard to make sure Jeff was going to be able to do more than he thought he could do,” said Crupi-Wicina, who today lives in Florida.

Her book is unremitting in its specific detail.

Soon Jeff underwent spinal fusion surgery, with doctors removing the tongs from his skull and, after taking a bone from his hip, transplanted it into his neck to stabilize it.

The family, in a donated jet, then flew Jeff to Colorado, where he received pre-rehab treatment.

The coffee pot in the hospital’s neurotrauma unit was “avocado green,” Crupi-Wichita wrote, while she and the mothers of other patients sat around a bruised table in “chrome-trimmed turquoise chairs.”

There, she and other mothers “purged ourselves of all the platitudes.”

She also began reading the Holocaust literature of survivor Elie Wiesel, “learning maybe for the first time that some things we must do go well beyond our strength and that at all costs, we must defy despair.”

Her son exhibited anger, almost daily firing her as his mother, she wrote.

But over time he responded to the treatment he received and returned to Kansas City in the spring of 1984.

Contractors, after the injury, had volunteered to remodel the family’s Lenexa home.

Jeff’s Bishop Miege friends, between classes, took turns carrying him and his wheelchair up and down staircases until an elevator was installed at the school.

“He was afraid for a while,” Crupi-Wicina said recently. “But he was lucky in that he had such a great bunch of friends who stuck with him the whole time.

“Those boys, they took it upon themselves to include him with everything and take him everywhere. They would come over to the house and say, ‘Hang on, Wicina, you’re going out,’ and just throw him over their shoulders.

“It was wonderful for him because he knew he was being treated just like his friends. He didn’t want to be set apart.”

Jeff graduated from Bishop Miege in 1986.

He went on to the University of Kansas, where he received help with daily tasks in his room on the first floor of Jayhawk Towers, and drove a specially equipped van while working with administrators to install curb cuts for those navigating the hilly Lawrence campus by wheelchair.

For several years he worked as a Kansas City area financial analyst until, his mother said, his body grew weaker from subsequent bladder infections that sometimes forced him to stay home from the office.

“Jeff was a hard worker, and he couldn’t stand not doing things,” Crupi-Wicina said.

By 1999, however, his body had been severely compromised, she wrote.

He died, by suicide, on April 15, 1999, at age 30.

“Jeff died by suicide but, in fact, he died of exhaustion trying to live up to the expectations he drew for himself,” she wrote.

Her own search for peace, meanwhile, continued.

In 1987 she left Catholic Social Services, starting her own private counseling practice. Ultimately, she worked for 30 years as a licensed professional counselor focusing on family trauma.

Her mother’s book had started as a diary, Genon Wicina said.

“From the day my brother was injured, she wrote and wrote and wrote,” she said.

“She had boxes of notebooks. She wanted it to be a self-help book. She didn’t want it just to be a book that made people sad — although to those of us who lived it, it is a very sad book.

“But for my mother the book was a way for others to realize that maybe there can be some hope in overcoming such an event in your life.”

Sometimes parents of children suffering football-related traumatic injury blame themselves, Ron Stiles said.

He cites the remarks of Gil Trenum, the father of Austin Trenum of suburban Virginia near Washington, D.C., who took his own life after suffering at least two football-related concussions in September 2010.

The elder Trenum read of the Stiles tragedy the following month and reached out to Stiles. The two soon met during an Overland Park grief conference.

“Gil was blaming himself,” said Stiles.

“I told him, ‘You know, if you are going to blame yourself for what happened with your son, then I will start blaming myself for letting Nathan play football. Then we’ll be on the same page.’ And he said, ‘Ron, there is just nothing we could have done, is there?’ And I said, ‘Now you’re getting it.’

“Sometimes bad things happen.”

Chin-ups for the Chiefs

The medical care and organized emergency response plans that were not available at Southwest High School in 1935 exist today.

“Things have evolved tremendously over a century,” said Dr. David Smith, a clinical professor at the University of Kansas Health System and medical director of its Youth Sports Medicine Program, which maintains contracts with four area school districts in Kansas.

Smith recalls how, when he was completing his medical training in the late 1980s, sometimes the availability of trained medical personnel at high school football games depended upon the financial resources of a particular school or school district.

Or, while such emergency care often would be available, it sometimes would be on an ad hoc basis.

While athletic trainers — medical professionals — often would be in place during games, “sometimes they would have been hired by different health systems or private groups,” Smith said.

If a physician would sometimes be on site, it often would be because the doctor had a personal relationship with the school, he added.

But in the decades since, the emergency response infrastructure for high school football has grown far more robust, he said.

One reason, Smith said, is the training now received by athletic trainers skilled in treating issues ranging from cuts and abrasions to more serious emergencies involving head injuries, cardiac events or instances of heat stroke.

A second component has been the development of formal emergency action plans, or EAPs.

Those were prompted, in part, he said, by the recommendation of several sports medicine organizations over many years.

In 2002, he said, the American College of Sports Medicine urged fitness facilities or health clubs have an automated external defibrillator, or AED, on site in case of a cardiac episode.

Later, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association urged the development of written emergency action plans at high school sports venues.

Such plans now are in place on both sides of the state line, he said.

“Today, for every high school we deal with, we have a written emergency action plan for every venue, and for several sports, not just football,” Smith said.

The Youth Sports Medicine Program contracts with 13 high schools and 14 middle schools in the Blue Valley, Shawnee Mission, De Soto and Lansing school districts.

At each school the program supervises athletic trainers who practice emergency action plans three times a year, Smith said.

And, while emergency ambulance response in Johnson County ranks among the fastest in the country, some school districts prefer to have ambulances onsite during games, he added.

Still, Crupi-Wicina today believes football is not a safe sport for high school students to play.

“High schoolers’ bodies are not ready enough,” she said.

Ron Stiles, meanwhile, cautions against any blanket statements.

“Every situation is different,” he said. “Ultimately, it’s going to be up to the families.”

The Stiles family still watches football — when family members are involved.

Ron Stiles’ grandson is now old enough to play junior high football.

His brother’s grandsons both played for Olathe West High School. This fall one of them will be playing college football in South Dakota.

Finally, the husband of Nathan Stiles’ sister Natalie coaches eight-player football in Archie, Missouri.

The family will attend those games, Stiles said.

Meanwhile, the Kansas City Chiefs will begin defending their Super Bowl championship on Thursday.

Mark McKee will be watching.

“I think it would be news if I didn’t watch the Chiefs,” he said.

So will James McGinnis — at GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium.

It’s now been almost nine years since he, playing as a senior linebacker for Olathe East High School, suffered a traumatic brain injury.

During a 2014 game against Olathe South High School, he collapsed near the sideline after being involved in a tackle.

A television crew working the game documented how both teams knelt while medical personnel stabilized James and took him to a waiting ambulance.

He remained in intensive care for 18 days.

His family then moved him to a Lincoln, Nebraska, rehabilitation center where he underwent more than seven months of treatment.

He later returned to Overland Park where he continued to receive speech, occupational and physical therapy.

In 2016, James was an honoree at the 29th Annual Amy Thompson Run for Brain Injury, where he led the 2K walk.

“This year he started running for the first time,” Pat McGinnis said recently.

“Now we do a 5K run once a month.”

Today, at 27, James continues to struggle with short-term memory and suffers from neuropathy and ataxia in his hands and feet, his father said.

That has not stopped him from speaking at Kansas City area therapy centers, sports banquets and before church groups.

He also attends the occasional Kansas City Chiefs game.

His parents hold season tickets and, in recent years, began taking James to games when they believed his balance and endurance had improved sufficiently to attend a three-hour stadium event.

The Chiefs, his father said, continue to be part of his son’s recovery.

Last year James celebrated each Chiefs touchdown with a chin-up.

“He did a lot of chin-ups,” his father said.

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016.