Aging in Place is a Struggle in Kansas City Older Adults are 'Entitled to Dignity'

Published September 21st, 2023 at 6:00 AM

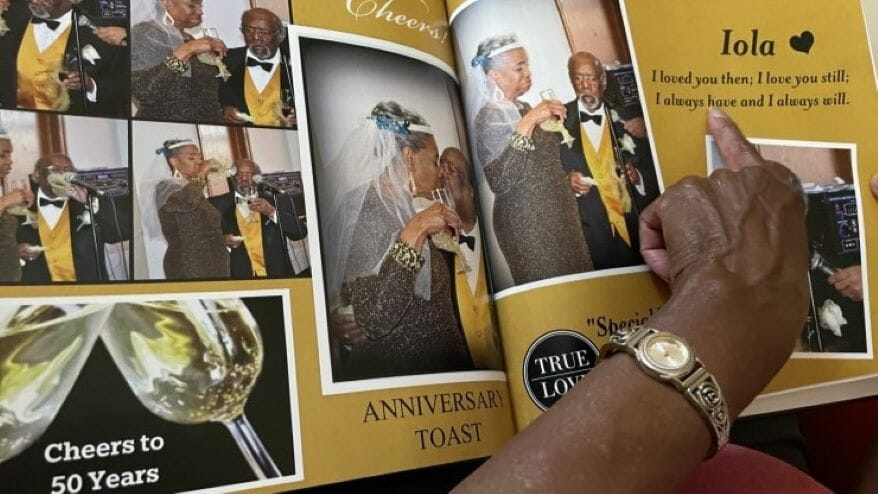

Above image credit: Iola Riley reminisces while looking at the photo album commemorating her and her husband Ernest's 50-year wedding anniversary. (Mary Sanchez | Flatland)Caregiving is an act of love. Countless gestures of kindness are required. They are essential for people aging in place.

A loved one might need help arranging appointments, deciding to stop driving, remembering to take medications, getting help bathing or moving out of a beloved family home.

For most people, it’s a challenge to help without undermining an older adult’s dignity and respecting the loved one’s right to make their own choices, especially if risk is involved.

For that reason and many others, caregiving is exhausting. It can be isolating. It can harm the physical and mental health of the person providing it.

Caregiving is generally unpaid labor and is most often done by a woman. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers caregiving a public health issue.

All things considered, a foreboding picture of an aging America is coming into focus. More than one in five adult Americans served as a caregiver to another in 2020, a total of 53 million people.

That’s a sharp increase from the 43.5 million who were doing so just five years prior, according to a recent survey published by the AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving.

Family caregivers provide an estimated $600 billion in unpaid labor a year.

And that’s an ever-escalating figure as the number of older adults surges.

In Kansas City, the number of people 65 and older is expected to double by 2030, compared to 2010.

Octogenarians, people in their 80s, are the fastest-growing demographic in the Kansas City region.

Most Americans, polling shows, wish to remain independent and in their own homes as long as possible. And parents often don’t want to burden their children with expanding lists of needs.

But how will Americans manage?

So much about society — reliance on cars for transportation, older housing stock not easily adapted to those with less mobility, and Western attitudes that discourage co-habitation between multiple generations — works against reshaping attitudes about aging and how we live.

Let alone the fact that sometimes an elder has outlived everyone else in the family, lives far from family, or is estranged from children or siblings who might otherwise help as self-sufficiency declines.

Here are stories of how some people are coping.

Flatland on YouTube

A Long Marriage, A Devastating Diagnosis

Iola Riley saw the tremors in Ernest about the time they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

“I noticed him shaking and I said to myself: ‘Lord, I hope this is not what I’m thinking. But I have to find out for sure.’”

She was right. Her husband has Parkinson’s disease.

But it took his wife pressing an internist and getting another doctor to eventually make a referral to a neurologist before the diagnosis was made in 2020.

Iola Riley is 81. Her husband is 91.

“I know what my responsibilities are to take care of him,” Iola said of her husband of 56 years. “And I can say it does put a toll on my body. But I keep right on moving.”

She walks with a quad cane, for extra stability.

Ernest does not.

Iola had long ago carefully planned their Northland home. The bedrooms are upstairs. But they can live on a lower level, with access to what they need.

Still, one doctor suggested the couple enter assisted living.

Iola refused.

“Assisted living would kill him,” she said. “And I said that I would end up dying behind him.”

At great expense, they gutted a bathroom and put in a large walk-in shower with more accessibility.

Her health struggles are significant.

A hip replacement didn’t heal correctly, leaving her in pain.

The breast cancer that first appeared in one of her breasts returned.

She opted for a mastectomy, not wanting to undergo chemotherapy or radiation, something she watched her sister endure.

“I’m doing all of this so I can get my stuff together to take care of Ernest,” she said.

Iola drives on city streets, rather than on highways. On days that she doesn’t feel up to driving, she calls a Platte County seniors service for a lift.

A doctor’s office that treats her husband gave a referral to a support group for caregivers. But then she was convinced that the group wasn’t a strong one, without being offered an alternative.

Their daughter lives in Maryland. A son lives in Kansas City. Iola also helped raise two of Ernest’s sons from his first marriage.

Music is an outlet, her place for “peace,” as is her church, where she runs a scholarship-giving foundation.

Iola held season tickets to the Lyric Opera and the Harriman Jewel Series for about three decades. But after retiring from the Social Security Administration, her budget didn’t allow for all of it.

Ernest retired from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

She keeps the Harriman tickets and buys a single ticket for the opera or the symphony if a specific performance intrigues her.

Ernest doesn’t understand why she keeps attending. Ernest thinks she should stop going after so many years.

Iola attributes that view to Parkinson’s.

She charts the changes in her husband, what she thinks can be attributed to Parkinson’s, then reports it to his doctors.

There’s the way Ernest drops conversations, shifting topics. And the hallucinations, such as insisting recently that the shine on the kitchen floor was spilled water. Or that ants were in the kitchen, and he dutifully swept them all up.

Iola leans on her faith. She attends the same Baptist church that she joined with her family as a young girl. Sometimes she worries that she’ll die first.

Ernest falls asleep easily, often in his chair, watching the television.

Iola has taken to peering at him, checking. She waits to see his chest moving up and down, confirmation of his breathing.

“I love him. Lord, I’m going to take care of him. But I know how it is working on my body.”

Politics, Policy and the Feminization of Poverty

Laura Loyacono is watching what she terms “the feminization of poverty” play out across America.

As a public policy expert, Loyacono notes that caregiving is most often done by a woman.

“Women are giving up jobs that have social security and pensions,” Loyacono said. “Half of the time, they’ve already done that to raise their own children and now they’re doing so to support their parents.”

This undermines women’s potential earnings, and their career upward mobility, along with the ability to accumulate savings for retirement.

Politicians are aware of the issue.

Paying caregivers a stipend was part of the Build Back Better Plan introduced by the Biden administration as part of an effort to bolster the middle class, she said.

But partisan wrangling stymied passage.

Last week, Loyacono attended the Show Me Summit on Aging and Health 2023 in Columbia, Missouri. The Missouri Association of Area Agencies on Aging, founded in 1973, sponsored the annual summit.

Gov. Mike Parson spoke, promoting Missouri as a welcoming place to retire, filled with services that people will need to remain in their homes and help for caregivers.

Most advocates say the state has a long way to go before it can fulfill that vision.

In January, the governor signed an executive order to create a “Master Plan on Aging” to “help reduce age and disability discrimination, eliminate barriers to safe and healthy aging, and help Missourians to age with dignity.”

Those are big goals, especially in a state where the legislature refused to expand Medicaid, which is a crucial part of providing care to lower and some fixed-income people. Eventually, expansion happened through a voter-approved ballot initiative.

In calling for the plan, the governor’s office noted that there are already more than 1.1 million Missourians who are 60 or older. It’s estimated that the state will have more older people than younger by 2030 and that the disparity will continue to widen.

Virtually every state in the union is facing a similar demographic predicament.

What it means in basic terms is that there will be more people in America needing help than younger ones able to provide it, or working full time, contributing to a tax base to help fund necessary programming and services.

Things like Meals on Wheels allow people to remain in their homes when grocery shopping or cooking has become difficult.

The meal service is sometimes the only time a senior might see another person during a day, Loyacono said.

Other programs provide stipends to cover modest changes to homes, like a ramp, grab bars in a shower, and tile where carpeting or rugs can limit mobility and increase the likelihood of a fall.

Falling and subsequent injuries are a leading cause of death for aging adults. And Missouri’s rate of such incidents is 31% higher than the national average.

One answer is PACE, which stands for Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. A new location, PACE KC Swope Health, is opening soon to serve Jackson County residents.

There, people can receive rides to get meals, social interaction, physical therapy and strength-building activities. The services are geared toward people 55 and older, to help with health and wellness so they can remain in their own homes longer.

There is also growing awareness for less visible groups of seniors.

Loyacono, through her advocacy work with KC Shepherd’s Center, is beginning to focus on the needs of the LGBT+ community. An LGBT+ person of color is more than three times as likely to live in poverty, she said.

Through roundtable conversations, Loyacono said, concerns have been raised about the community’s comfort levels with doctors, the fact that some people do not have biological children to turn to, or they’ve been estranged from family. Many are now at retirement age, but came out decades ago, in eras with far less societal acceptance.

A Son Returns to ‘Look After’ His Mother

Derek Phillips left Kansas City 50 years ago, a young man pursuing his college education and eventually, a dance career.

He became a teaching artist at the Cowles Center in Minneapolis.

But now, except for a few weeks each year, he’s primarily living with his 93-year-old mother in the Kansas City house that’s been the family home since 1968.

“She doesn’t have any serious health issues,” Derek said. “I describe my role as more of looking after her as opposed to taking care of her.”

Still, he acknowledges, “it’s a lot of work.”

Louvenia Kelley Phillips is a contemporary and lifelong friend of many well-known Kansas Citians, like former mayor pro tem and Ad Hoc Group Against Crime co-founder Alvin Brooks and restauranteur Ollie Gates.

She’s an avid reader of The Call, and a proud member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first intercollegiate African American sorority, which she joined as a young woman attending Lincoln University.

“She’s quite independent,” her son said, laughing. “Sometimes too much so.”

A daughter helps with some personal care, but the family matriarch still enjoys cooking and choosing her outfits for church, especially her hats.

Derek thinks that his mother might adapt to an assisted care facility, but strongly believes that she’s happier in her own home.

“But when I’m in the house with her,” he said, “it’s clear to me that she should not be by herself.”

Before retirement, his mother was a claims authorizer for the Social Security Administration, adept at organizing paperwork. But now, sometimes, she’ll stare at a bill, and at some point, stop reading or understanding, her son said.

Decision-making is difficult.

Another issue is clutter. His mother misplaces things.

Derek picks things up but is careful not to disturb too much.

Louvenia took personal photos beginning in the 1940s, and has an incredible collection, documenting the family’s story. She has five great-grandchildren and four great, great-grandchildren.

She’s close with her best friend from high school, who still drives, and many lifelong friends from church.

“She’s very social,” Derek said. “I’m convinced that’s one of the reasons she’s done so well.”

The family is hyper-conscious, always looking for signs of dementia, a condition their mother’s older sister had before her death.

The family often jokes about some of their mother’s care, softening the situation.

She uses a walker for extra balance, and the version with wheels and a seat is known as “the Cadillac.” The raised seat on a toilet is called “the high-rise.”

Louvenia calls her cell phone the “flip flop.” But it is becoming more difficult for her to learn new things, like the technology involved with the television.

Several years ago, Derek and his sisters tried to convince their mother to stop driving. They weren’t successful.

But more recently, their mother drove and at one point, said that her “leg went out.”

She told her son, “I stepped on the brake, and it didn’t feel like the car was slowing down.”

The next day, she drove to a nearby church parking lot, to test herself.

Driving, she concluded, was an issue because of her neuropathy, especially in her right leg.

“She gave up driving completely voluntarily because she felt unsafe,” her son said, as an example of how his mother is more than capable of making her own decisions.

Derek occasionally attends a support group for caregivers at the Landon Center on Aging at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Hearing other caregiver stories, such as cases of advanced Alzheimer’s, leaves him grateful for his mother’s relatively good health.

“The one thing that I’m probably not doing is, I’m not taking as good of care of myself as I should be,” he admits.

Derek had back surgery shortly before he began shuttling more often between Minneapolis and Kansas City. Teaching dance would be good for him. But most of his dance connections aren’t local.

“I’m feeling this need to be around my mother,” he said. “I find myself in this sort of vigilant mode, watching her, watching her.”

‘Taking Care of Grandma’

Rachel Hiles’ grandmother was an only child. And Hiles is an only child. She was raised by a single mother.

Those facts alone set up the eventual reality that Hiles would become her grandmother’s caregiver. She was still in her 20s.

Barbara Lynn Hiles was born in 1936. She was widowed in 1997 and outlived a son.

A reading specialist in the Blue Springs School District, she led an independent life, for years a doting grandmother to Rachel.

Until one day, she fell. And that began an odyssey of health issues for the then 78-year-old.

There were pain medications, surgeries, a perforated colon and eventually a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

Rachel hired help for her grandmother. She tried to continue working, installing cameras so that she could monitor if her grandmother had fallen in her home or needed help.

“I fought tooth and nail to keep our houses separate for as long as possible because I wanted my own privacy,” she said.

Hiles also produced “The Headcaregiver in Charge Handbook,” a blog and a jovial YouTube video, a rap that features herself and her grandmother during their days together, “Taking Care of Grandma.”

Caregiver Art

She was at her grandmother’s side through COVID and as her mobility decreased from a walker to a wheelchair and eventually to a mechanical lift to help her get out of bed.

They lived together until her grandmother’s death in January 2022.

Now, she’s founded a nonprofit support group called “Sandwiched, Family Caregivers of Kansas City.”

Her design background helped guide the creation of the organization’s website.

“I want people who come there to immediately feel like they’ve gotten a warm hug,” the 36-year-old said.

Hiles, just last week, decided on another model to support caregivers.

She’s been holding virtual support group sessions but has realized that a greater need may be to bring support services to caregivers, like home visits.

“The problem is, people are so tired and so taxed out, that they just can’t attend, even though it would be beneficial for them,” she said.

She remembers how isolated she became with her grandmother.

“There are not enough nursing homes in this country to take care of everybody who needs help, nor can the people afford them,” Hiles said.

Caregiving between family members, and building supportive networks around those caregivers, will become increasingly essential in the U.S., she said.

“We have a responsibility to our elders to help them maintain their independence as long as we possibly can,” she said. “They are entitled to dignity.”

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS/Flatland. Cody Boston is a multimedia producer for Kansas City PBS and the producer of the Flatland in Focus.

Support for “Age-Old Questions” is provided by William T. Kemper Foundation, Commerce Bank, Trustee. Additional support is provided by Husch Blackwell.