Kansas Struggles with Shortage of Alzheimer’s Care Workers Study Declares State a Dementia Care ‘Desert’

Published September 7th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: The Alzheimer's Association estimates that 1.2 million additional direct care workers are needed to meet demand by 2030 - more new workers than any other single occupation in the United States. (Courtesy | Alzheimer's Association)The Alzheimer’s Association recently released a special report focusing on improving care for the memory-destroying disease.

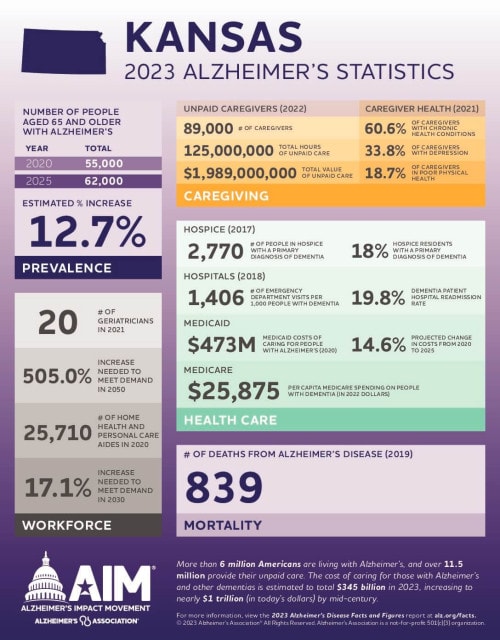

The report, which among other things looked at national workforce and caregiver data, found that Kansas has a dramatic shortage of health care workers to treat people with dementia.

According to the report, about 62,000 people are expected to have Alzheimer’s disease in Kansas by 2025. Meanwhile, there are just 20 geriatricians statewide. To meet the predicted long-term demand, the state would have to increase those numbers by a whopping 505%.

This data reinforces the shortage noted in a 2017 report by the Alzheimer’s Association finding Kansas is one of 20 states known as “dementia neurology deserts,” meaning Kansas is expected to have fewer than 10 neurologists per 10,000 people with dementia by 2025.

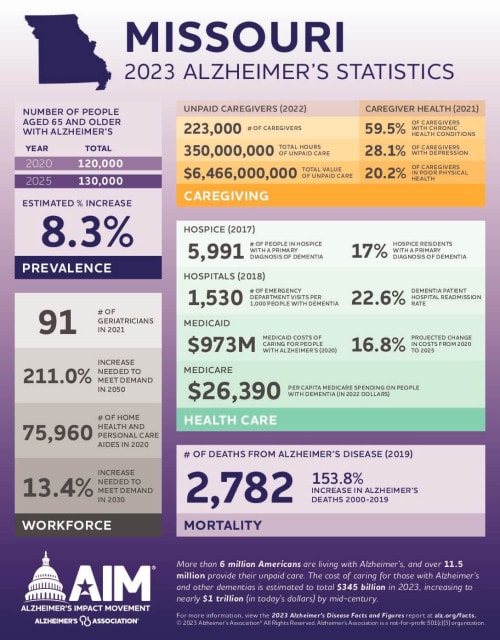

To be sure, Kansas isn’t the only state grappling with workforce shortages in this space. Missouri, for example, would need to increase its number of geriatricians by 211% to meet expected demand.

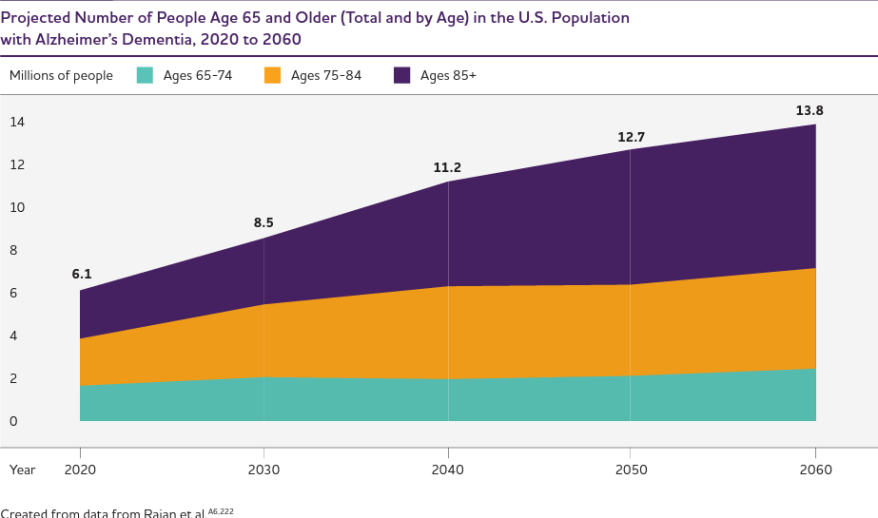

But the number of aging Baby Boomers, combined with low staffing and new medications that make catching the condition early crucial, has left the industry scrambling for ways to find solutions to the problem.

Not Just a Rural Issue

Annette Graham, executive director of the Central Plains Area Agency on Aging, said the workforce shortage in geriatrics and older adult mental health is “dismal.”

Part of the reason is the old refrain that Kansas is a rural state that, like many others, has a difficult time recruiting all doctors – particularly specialists. But it’s not the only factor contributing to the dwindling numbers of doctors available to treat older patients.

In 2019, Graham was a member of a task force created by Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly to provide recommendations for ways the state could improve Alzheimer’s care. During their meetings, a Wichita resident told their story of having to leave the state to get a diagnosis.

Robert Miller, owner of CarePitch and a care manager consultant in Wichita, said there aren’t enough doctors to manage patients there. He consistently has clients coming to him asking where to go for care. But he only knows of three neuropsychologists in Wichita – and one of them no longer works with geriatric patients.

Patients are facing the same issue in the Kansas City area. Dr. Jeff Burns, co-director of the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said they are booking new patients six months to a year out.

“There is a huge need, and we struggle every day with it,” Burns said. “We get more patient referrals than we can see in the memory clinic. The aging population is the fastest-growing population and one out of three people over the age of 85 have Alzheimer’s.”

Burns said one reason there are so few specialists to treat this group is economics. Put simply, there isn’t a lot of financial incentive to go into geriatrics compared to other specialties. In fact, during medical school, he had people trying to talk him out of going into this area because of the modest pay.

“Dementia care is not something that pays the bills for a health system,” he said. “There is a heavy burden on staff and physicians because the families need a lot (of attention) and much of it doesn’t pay well. It’s hard for health systems to invest a huge amount into it.”

Another issue is ageism, which Graham calls “an insidious discrimination.” The medical field is focused on healing and curing. But, because a lot of conditions can’t be cured as we age, it’s difficult to recruit a young workforce.

Delayed Diagnoses

Taking months, to a year, to get a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s causes critical delays in crucial care for several other conditions that can appear like Alzheimer’s. Several issues older adults face mimic dementia but are reversible when caught and treated. Things like depression, urinary tract infections, B12 deficiency, low thyroid, delirium and hearing loss can all make people isolated, antisocial, and behave abnormally, Graham said.

“I had a friend whose older parent was hospitalized for issues that looked like dementia, only to find out their confusion, memory loss and erratic behavior was due to overmedication, which happens lots in elderly patients,” Graham said. “We need docs who understand these issues and can make a differential diagnosis.”

The newest drug on the market to treat Alzheimer’s has also reinforced the need for early diagnosis. Lequembi, which received full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in July, has been shown in clinical trials to slow the progression of cognitive decline in people with early-stage Alzheimer’s.

Soaring Demand

“For early Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment, those people don’t usually end up in our clinic for a while,” Burns said. “People are in denial or bouncing around from doctor to doctor. But now there’s a treatment specifically designed for that population, so we are going to see a big influx of new people anxious to get in to see us and we can’t meet that demand.”

Getting an early diagnosis can also help save vast amounts of money.

The 2023 Alzheimer’s report noted that, if 88% of patients who develop Alzheimer’s were diagnosed when they had mild cognitive impairment, rather than in later stages, it could save $7 trillion. These savings would be from lower care costs right before and after the diagnosis and lower medical and long-term care costs over time.

“When there is an early diagnosis, people are participating in decision-making and collaborating with their medical team and family and can make financial decisions,” said Juliette Bradley, director of communications for the Central & Western Kansas Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association. “And when they are diagnosed later, families often panic and may end up going to higher-priced facilities.”

Coordinated Response

Bradley said one of the challenges with Alzheimer’s and dementia treatment is the doctors that end up seeing many patients 60 and older are emergency medicine specialists. People end up in the emergency department after a fall or other injury unrelated to Alzheimer’s and the doctors diagnose them while in the hospital – and that’s only if the providers are trained to do an assessment.

“They are treating these patients, but shouldn’t be,” she said. “Geriatricians and neurologists are the best equipped. It’s like going for groceries and ending up in the hardware store. They are in the wrong place.”

With a clear dearth of specialists available to treat people with Alzheimer’s, one might think much of the care is being pushed to primary care doctors. But this is not often the case. Bradley said primary care doctors typically don’t offer cognitive assessments to patients over the age of 65 during checkups or other appointments.

“The mindset among a lot of primary care doctors is, if there is no mention of it by patients, I shouldn’t be concerned there is a problem,” she said.

In the 2023 Alzheimer’s report, 97% of primary care doctors surveyed said they wait for patients to mention symptoms of dementia or request an assessment, rather than offering one on their own. The challenge with waiting for patients to bring up the issue is that patients and their families are often hesitant to do so. There is emotion, fear and stigma surrounding an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Training is also an issue for many primary care doctors. Unless they have a residency where there are a lot of older patients or ones who have dementia, they don’t receive a lot of information about the specific needs of this population while in school.

Necessary Training

This is one reason the Alzheimer’s Association has offered a national telementoring program for primary care doctors to educate them on working with Alzheimer’s patients. During the six-month-long program, physicians are taught things like how to recognize cognitive impairment, assessment tools, how to diagnose dementia, specifics of referrals and specialty testing, and how to manage these patients and work with caregivers.

Burns said the University of Kansas has worked to develop training programs geared toward helping providers better understand Alzheimer’s care. They offer a clinical fellowship for physicians and a six-month-long dementia fellowship for advanced practice providers like nurse practitioners.

KU has also spent the past few years cultivating a cognitive care network including about 110 primary care doctors. Burns and colleagues provide education on the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s and work to help doctors engage social workers and nurses to provide treatment closer to home for these patients.

AN ESTIMATED 1.2 MILLION ADDITIONAL DIRECT CARE WORKERS WILL BE NEEDED BETWEEN 2020 AND 2030 — MORE NEW WORKERS THAN IN ANY OTHER SINGLE OCCUPATION IN THE UNITED STATES.

Alzheimer’s Association

“Are we going to solve the problem with more specialists? Probably not, because they are not out there,” Burns said. “We are trying to innovate with new models of care. We are trying to create a support for community physicians to fill the gaps in care and treat patients closer to home.”

By educating primary care physicians, Burns hopes those providers will be able to evaluate patients for Alzheimer’s and manage many in their own practices. Then unusual or more difficult cases can be sent to specialists.

“I don’t think primary care doctors or specialty care is the ultimate solution,” Burns said. “Bridging the two is the best way forward.”

Tammy Worth is a freelance journalist based in Blue Springs, Missouri.

Support for “Age-Old Questions” is provided by William T. Kemper Foundation, Commerce Bank, Trustee. Additional support is provided by Husch Blackwell.

My 91 year old mother has late stage dementia. She lived with me for 5 years and I finally decided to place her in a memory care facility. It was expensive and the care was pathetic. I moved her to a different facility and again it was expensive and the care is pathetic. I go every day to assist with her care and have another lady assist a couple of days a week.

We need help!! I watch as caregivers and med techs ignore the needs of the residents. Allowing the residents to miss meals, fall, and spit out medications. Toileting needs are ignored.

If I try to assist a resident (not my mother), am told not to help.

My mother is in a private facility and I understand your investigation doesn’t cover private facilities but I just wanted to comment.