Kansas Community Colleges Reaching a Crossroads Kansas’ 19 community colleges offer a pathway for 96,000 students to pursue postsecondary studies. But precipitous enrollment declines, aging campuses and funding struggles cloud the future of these institutions, which are often economic linchpins in small cities.

Published December 8th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Cowley College was established in 1922 as Arkansas City Junior College. For 30 years, it existed in the basement of the Arkansas City High School. In 1950, Galle-Johnson Hall was built, the beginning of today's 15-acre campus in downtown Ark City. (Jeff Tuttle | The Journal)If Joe Blake had followed family tradition, he’d have headed for the University of Kansas straight out of high school. His parents are KU graduates and his older brother and sister enrolled there as freshmen.

But when Blake graduated from Hutchinson High School in the spring of 2020, he drove south to Arkansas City and Cowley College, a community college whose campus fits into a few blocks of a sleepy downtown.

Blake had his reasons. He’d been a star tennis player in high school, and Cowley offered him a scholarship and the chance to continue competing. He also had his sights set on a sports broadcasting career, and Cowley has a strong mass communications program. Blake plans to complete his bachelor’s degree at KU’s School of Journalism.

As he finished up his time at Cowley, Blake had no regrets about first going to a rural community college with an enrollment of about 3,600 students.

“I ended up being the voice of Cowley soccer this year,” he says. “And the tennis has been phenomenal.”

Blake is one of about 96,000 students who connected with a Kansas community college last academic year for credentials that include associate’s degree courses or training certificates. His experience highlights why public two-year schools are popular and, for many students, essential, even as the schools face headwinds.

Lawmakers and others in Kansas are calling for affordable education opportunities beyond high school. Current and prospective employers depend on community colleges to equip workers with the training and knowledge to thrive in today’s economy. Lawmakers recently created and expanded the Kansas Promise Scholarship program, which provides a free education at community colleges and technical schools for qualifying students in high-demand fields.

Yet enrollment at Kansas community colleges has plummeted in recent years. Campuses are aging and funding is a persistent headache.

As the state’s community college network moves into its second century of providing affordable postsecondary education for Kansans, questions about its viability grow more acute.

“We need advocacy,” says Dennis Rittle, who served as president of Cowley College for seven years before departing the post in July for a job in Arkansas. “We’re always fighting for the crumbs and trying to make sure we can keep our doors open and our bills paid, versus really getting out there and changing Kansas in a positive way.”

Kansas Community Colleges are Plentiful, Residential and Sports-focused

The birth of community colleges in Kansas dates to 1919, when college-level programs were established as part of public school systems in Garden City and Fort Scott. A 1965 state law enabled two-year schools to operate independently of school districts, with their own governing boards and taxing authority.

From the start, community colleges presented an option for high school graduates who weren’t willing or able to attend a more expensive four-year university. Over time, the schools moved into the workforce domain, offering training and job certification to adults of all ages. Across Kansas and the nation, community colleges are a leading avenue of opportunity for low-income, first-generation and immigrant students.

Today, 19 public community colleges are scattered throughout Kansas, and most have multiple locations. In addition, the state has seven technical colleges, which offer workforce training but not, usually, general college courses.

Compared with nearby states, that’s a lot of schools. Missouri, with a larger population, has 14 public two-year colleges. The Association of Oklahoma Community Colleges lists 12 members.

Johnson County Community College, with a sprawling campus in Overland Park and a reliable stream of income from a sales tax in the state’s wealthiest and most populous county, served about 26,000 students in the 2021 academic year. That’s a larger head count than the Kansas Board of Regents reported for any of the state’s public universities.

But JCCC is an outlier. Most Kansas community colleges are located in rural areas and serve about 2,000 to 3,000 students on their main campuses.

And those schools are notably more residential and sports-focused than most of the nation’s community colleges.

While only about one quarter of the nation’s 936 public community colleges have on-campus housing, according to research by the American Association of Community Colleges, dorm options in Kansas are nearly universal. Only JCCC is exclusively a commuter campus.

And while about half of the nation’s two-year colleges have intercollegiate athletic programs, every community college in Kansas offers men’s and women’s athletics.

“Athletics is important to community colleges in Kansas,” says Carter File, president of Hutchinson Community College. “It’s one of the ways we can really integrate ourselves into the community and something the community can take pride in.”

In some ways, Kansas community colleges have existed for years as a model for what colleges in other states wish to become.

“What I have learned is that rural colleges really need two things – they need athletics and they need residence halls,” says John Rainone, president of Mountain Gateway Community College in Clifton Forge, Virginia, who just wrapped up a term as chair of the American Association of Community Colleges Commission on Small and Rural Colleges.

“If we really want students to think about us as a first option, I do think students are expecting that we have some of the amenities that four-year colleges have,” he says.

On-campus housing and the chance to play sports bring students from around the world to small Kansas towns like Arkansas City, Parsons and Concordia. They provide activities and entertainment and youthful energy to aging rural communities.

But as Kansas’ experience demonstrates, sports and dorms alone aren’t enough to keep small community colleges relevant in a turbulent economy.

What Happened to the Students?

Despite an ongoing push to enroll graduating high school seniors in some kind of postsecondary academic or vocational program, the overall enrollment in the state’s community colleges has been declining for at least 10 years.

In 2022, a total of about 96,000 students signed up for college credit or vocational courses at the 19 community colleges. That’s nearly 16% fewer students than in 2017, according to Kansas Board of Regents data. Some community colleges have seen enrollment drops approaching 30%.

The picture over 10 years looks even worse. Based on a report issued in March, community college enrollment dropped by 27%, while enrollment at the state’s public universities dipped by about 3%. The smaller technical schools fared much better, with a recorded increase in enrollment of 61%.

Community college enrollments have always been tied to economic trends, often to the schools’ advantage. Laid-off adults rushed to campuses during the Great Recession, for instance, seeking to upgrade their skills and credentials.

But that kind of bounce didn’t happen in the pandemic, when classes were remote and the federal government was offering generous unemployment benefits. And in the current economy, employers desperate to fill job openings are waiving education and training requirements that students have traditionally obtained at community colleges.

“We hear all the time from our area industries, our regional industries: ‘I just need somebody who’s going to show up for work every day, and pass a drug test,’” says Marlon Thornburg, president of Coffeyville Community College.

The effects of the labor shortage are hitting some of the schools’ most popular programs, such as a collaboration between Coffeyville and Pratt community colleges that trains high school graduates to install and repair electrical power lines.

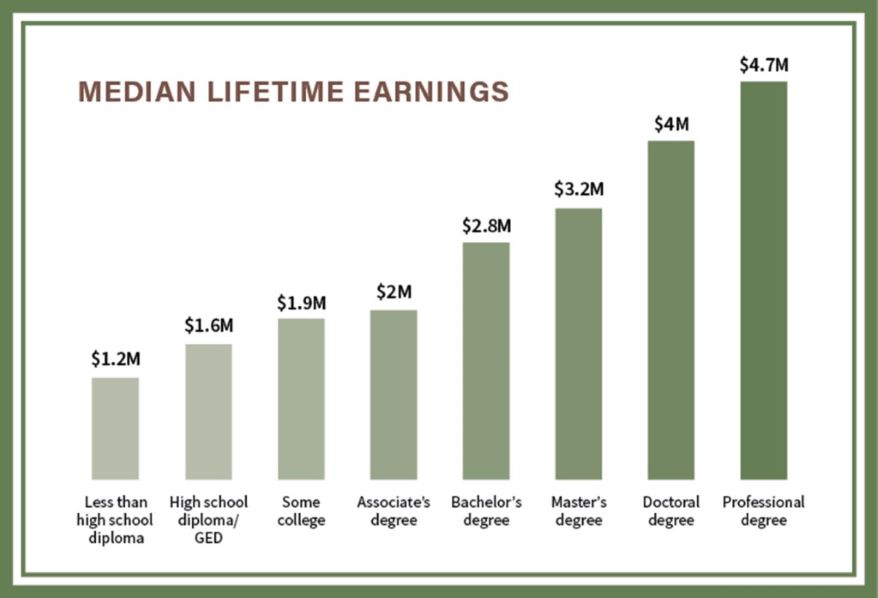

In just two years, for a little more than $25,000 in tuition, fees and living expenses, an in-state student can graduate with an associate’s degree and a certification for a job that pays a starting salary of nearly $50,000. After a five-year apprenticeship, earnings exceed $77,000, according to KSDegreeStats.org, a tool created by the Kansas Board of Regents.

But right now, many students aren’t staying for two years.

“The companies need workers,” Thornburg says. “After the first year of the lineman program, a lot of kids do an internship that first summer. And if they do well on their internship, those companies don’t want the kids to go back to school. They’re hiring them right now.”

Skeptics and Champions

The steady enrollment declines feed an undercurrent of discussion about the viability of Kansas’ system of small, independent community colleges and the way they’re funded.

“Kansas has stagnant population growth, fewer Kansans in the workforce, shrinking rural communities and an overall aging population,” says Kansas Rep. Kristey Williams, a Republican from Augusta, who has questioned the cost and necessity of supporting 19 community colleges.

Williams, who responded to questions in an email exchange, notes that the two-year school in her district, Butler Community College, lost 30% of its enrollment in the past decade.

“Many students are moving to online options, which provides a source of revenue but doesn’t require the large footprint necessary when enrollment was in-person and growing,” she says.

Alan Cobb, president and CEO of the Kansas Chamber of Commerce, says he is frequently asked about the administrative costs of the community colleges.

“Obviously, Garden City is going to have some programs that are different from Johnson County Community College, so you need some flexibility,” Cobb says. “But do you need a president at every community college? I think we should ask that.”

Talk of mergers of community colleges, or of community colleges and four-year colleges, pops up every so often in legislative hearings or other forums. But because community colleges operate independently without any statewide governing authority, it’s hard to discern who besides a governor would initiate a conversation about consolidation.

“There are people who whisper in the halls. It’s very rarely discussed in a formal setting,” says Heather Morgan, executive director of the Kansas Association of Community College Trustees.

Skeptics and advocates agree on one point: They say the state’s system for funding community colleges is hopelessly outdated.

A cost model created in the early 2000s calls for the Legislature to pay roughly one-third of the cost of instruction and related services for community colleges. The remaining two-thirds is to come about equally from student tuition payments and local property taxes.

But the state hasn’t paid its share for years. In the 2020 fiscal year, state appropriations amounted to less than 20% of revenues for the community college system.

That leaves locally elected boards with the difficult choice of either raising tuition, increasing local mill levies or both.

The reliance on property taxes in particular bothers Williams. She notes that only about 20% of Butler Community College’s enrollment comes from the home county. Most students commute from neighboring Sedgwick County.

“Sedgwick County is the major benefactor of the property taxes paid by Butler County residents,” Williams says.

Many community college leaders say they, too, would like the Legislature to pick up a greater share of their funding and shift the burden off of property taxes. They’d also appreciate more state help with maintaining their buildings and financing new ones.

“Physical building issues are preventing us from educating more Kansans to meet the workforce demands that are acute across the state,” Morgan says.

Community colleges are somewhat hampered when it comes to making their case in Topeka. Few of them can afford lobbyists. Apart from Morgan, there is often no one to take up their cause.

Each college is governed by an independent board of trustees. Unlike in most states, Kansas has no governing or regulating authority for two-year schools. While the Board of Regents governs the state’s six universities – hiring their presidents, setting tuition rates and approving contracts – community colleges make those decisions at the local level.

“The regents champion the universities,” says Rittle. “I’m not bashing them or saying they don’t care about the community colleges. But we don’t have that champion that says, ‘The only reason we’re here is to help you be successful.’”

Essential Resource for Rural Communities

Of course, plenty of people around Kansas are pulling for community colleges to succeed.

“I think the coolest part about the Kansas community college network and also the trade school programs is that a majority of them are located in rural areas,” says Trisha Purdon, director of the Kansas Office of Rural Prosperity, a division of the state Department of Commerce.

“They really are the integral resource that these rural communities depend upon,” she says, “not just for new blood coming into the town, but also for ongoing training programs that really ensure that rural communities continually evolve and learn new skills.”

By some measures, investment in Kansas’ community colleges is a bargain. A 2019 economic impact study by labor market data company Emsi found that Cowley College adds $265 million to its region’s economy annually through jobs and the spending impacts of students, staff and alumni.

Researchers examined the 2016-17 fiscal year and found that federal, state and local taxpayers gave Cowley College $13.5 million in that period. The return on that investment, in higher lifetime earnings for students and increased business output, is projected to be $45.8 million.

The same firm, Emsi, found that Kansas City Kansas Community College in Wyandotte County added $182.3 million to its local economy in a given year. That report estimates that students who attended KCKCC in the 2016-17 school year will earn a combined $186.3 million more in pay over their working lives because of the education and training they received at community college.

Because of their scattered nature, many of the achievements of Kansas community colleges never become widely known.

In Concordia, Cloud County Community College was one of this year’s 25 semifinalists for the Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence. The Aspen Institute awards the honor every two years, based on metrics such as retention and graduation rates and success factors for low-income and minority students. Although Cloud wasn’t one of the 10 finalists, it can still claim bragging rights.

“It’s a great time to be at Cloud, in my opinion,” says college President Amber Knoettgen, who obtained her associate’s degree at the school and played on its basketball team. “When we’re recruiting, we’re able to say that we’re one of the top 25 community colleges and technical schools in America.”

By mid-August, students were filling up dorms at Kansas community colleges and sports seasons had begun. Enrollments still looked low and finances still looked uncertain. But colleges remained secure of their place in their communities.

At Garden City Community College, plans were underway for a new building to expand John Deere ag tech training, and industrial maintenance and welding classes. Students from around the nation and world were coming to campus to play sports or take courses they can’t find at home. In the spring semester, 43 states and 90 nations were represented on campus, college President Ryan Ruda says.

Ruda, who has been at the college for 23 years and served as president since 2019, said he networks constantly in his community to try to make sure the school is responding to needs.

“We are a transfer institution. We are a technical institution. We provide fine arts and athletics,” he says. “Community colleges really try to be all things to all people.”

Barbara Shelly is a freelance writer based in Kansas City.