The Tainted History of Infant Care, Parent Empowerment and Education A Quick History Lesson on Feeding Infants

Published June 7th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: The infant formula shortage happening now has resurfaced pre-existing disparities mothers of color and low-income families face. This story explains the history of how that happened. (Vicky Diaz-Camacho, Library of Congress | Flatland)If only parenthood always felt and looked like advertisements from the old days, which depicted such ease and joy.

A babbling baby and a toothless grin. A picture-perfect family, every piece of clothing and hair in place.

But behind those advertisements were statistics showing troubling trends and a vexing history. Both infant and maternal mortality rates were high. It was even worse among Black women and women in historically lower socioeconomic statuses.

This mosaic of issues back then parallels those happening today. The ongoing infant formula shortages across the nation have resurfaced age-old inequities in maternal health care across racial and socioeconomic lines.

For context, in the 1800s nearly 45% of children didn’t make it to their fifth birthday, according to Statista. Over the years those rates decreased for some demographic groups more quickly than others.

Researchers, midwives and medical experts wrote study after study on mothers and babies, only to find patterns of malpractice, discrimination and racism. Many new parents were neglected and not given the education they needed to learn how to feed their children.

But this was an issue even long before then. Thousands of years before infant formula was created, women in wealthier societies and privileged social classes enslaved Black or immigrant women, while others hired typically poor or peasant women, to breastfeed their children.

Find more statistics at Statista

Women who breastfed their enslavers’ children were called “wet nurses.” For days on end, they’d feed other babies and be estranged and unable to nurse their own children.

Wet nursing was commonplace in Europe and the Americas in colonial times. In the late 1800s, though, these practices began to be looked down upon. Reasons varied, such as theories that breast milk could transfer cultural to psychological differences and influence the infants.

An excerpt of a historical article published in the Journal of Perinatal Education explained evolution in the practice:

“Breastmilk was deemed to possess magical qualities, and it was believed that breastmilk could transmit both physical and psychological characteristics of the wet nurse. The belief resulted in protests against the hiring of women for wet nursing and, once again, a mother nursing her own child was valued as a saintly duty.”

Then there was what’s called dry nursing, also known as bottle feeding. Doctors would later decry certain methods because it was difficult to sanitize bottles properly and cook the bacteria out of the milk safely for the young infant’s stomach.

Infant formula, as historical accounts show, was created to help mothers who were unable to feed their infants, many of whom died of starvation.

Parents and doctors swore by different methods, causing a bit of confusion on what was proven to be most beneficial to the child. Acceptance for breastfeeding seesawed over time, becoming markedly more popular in the 1990s after groups began to denounce the benefits of infant formula.

However, the racial disparities in regard to access to care and education continued to widen throughout the years.

Shalese Clay, program manager at Cradle KC, is focused on informing the policy behind maternal health care and justice. Clay said the group recently launched the Maternal Community Health Worker Initiative because of the worsening mortality rates among mothers and infants of color in Kansas City.

“I have to give this quote (by) Dr. Sharla Smith, (who) runs the Kansas Birth Equity Network. She put it so simply: ‘Birth outcomes were better during slavery than they are today,’” Clay said.

“Racism is a public health crisis. So until it’s addressed, we will still be in this tug of war.”

How Formula was Formulated

Social determinants of health studies have shown the correlation between stress, food deserts, social status and health status.

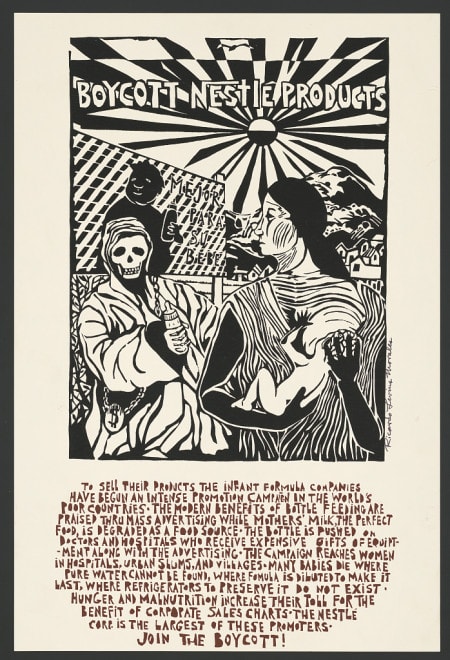

What has caught the eyes of maternal and infant health care advocates for years is the history of how formula was first introduced and to whom it was targeted.

The implementation of alternative infant food was popularized in the 19th century, according to the Journal of Perinatal Education.

While evidence shows that infants have been bottle fed animal milk as far back as 2000 B.C., the formula industry as a business took off in 1885 with John B. Myerling’s invention of evaporated milk, dubbed “safe” by pediatricians.

Today, baby formula and food products are a $7 billion industry.

In the later part of the 1880s, Myerling’s product was popular to feed babies. More parents began to trust and purchase formula in the 1920s through 1940s as the burgeoning pediatric field began to grow.

In 1929, the American Medical Association (AMA) created a group called the Committee on Foods to “approve the safety and quality of formula composition,” according to the Journal of Perinatal Education. A section of that journal entry reads: “By the 1940s and 1950s, physicians and consumers regarded the use of formula as a well-known, popular, and safe substitute for breastmilk. Consequently, breastfeeding experienced a steady decline until the 1970s.”

More women were joining the workforce and labor laws didn’t consider nor provide support for the parents whose bodies fed their children. This was the case worldwide, identified in this research article by Elizabeth Tansey, a historian of medicine.

“Their social emancipation meant that many weaned their babies soon after birth,” Tansey wrote.

Throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, activists began to speak out about racially targeted advertisements and the lack of regulation on infant formula.

There were problems with formula safety. So much so that in 1980 a bill was proposed during the Jimmy Carter administration and signed into law.

It amended the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to “strengthen the authority under that Act to assure the safety and nutrition of infant formulas,” which can be seen below.

These laws don’t do enough, advocates say.

Thompson said parents aren’t given good, clear information before or after the baby is born. It all depends on the birthing team they select and whether or not they have a supportive network of experts such as doulas, midwives or a trusted obstetrician.

And, a lot of times, medical literature or guidance doesn’t consider the parent’s wishes.

Thompson believes that this history in breastfeeding and formula creation explains the root of the shortage problem we’re seeing now.

Racial inequities, brought on by policies and aggressive marketing campaigns, would widen the gaps in maternal, infant and lactation care in general. That’s the crux of a book by Andrea Freeman, who authored “Skimmed: Breastfeeding. Race. Injustice.”

“When formula first became widely available as part of pediatricians’ efforts to medicalize motherhood, working Black women needed it the most,” Freeman wrote in a blog for Stanford.

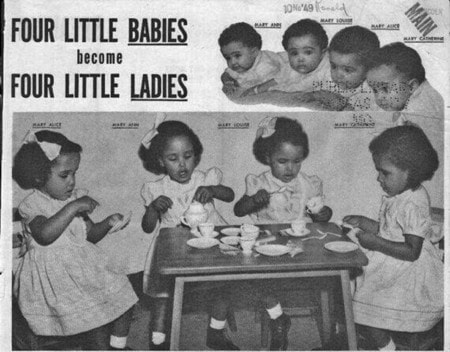

Limited and unequal access revealed how society perceived some communities, Freeman concluded. The starkest example she outlined was a formula company’s use of Black quadruplets in their campaign.

These trends have long legs. The needs of kids from lower-income and marginalized backgrounds went unmet then and continue to be unmet today.

When infant formula was popularized in the late 1920s, the industry further cemented the widening racial disparities as it connects to food access, health and maternal health care.

The treatment of Black and other parents of color in a hospital setting has also shown that outdated stereotypes about pain persist and that medical school students are still being taught using the same medical literature.

‘Such Distrust’

Advocates say discriminatory practices over the years had a lifelong influence on how communities behave and how medical care is perceived now.

“For Black and brown communities, … really one of those major points is that there is such a distrust in and of itself,” Thompson explained. “You’re looking at the medical providers, and it doesn’t seem like they have attempted to do anything to build that trust within the community that they serve.”

That’s where Cradle KC is hoping to step in, partnering with local community health groups and churches. It’s about meeting families where they are.

“I feel like history is a little bit repeating itself,” Clay said.

She and her team at Cradle KC are now focused on preventative measures that build trust in her community. One is the Queen Village Project.

She added: “The goal is to eliminate stress with Black women early on. So not just birthing bodies, but Black women as a whole.”

But she wants parents to know they can find alternative support networks while understanding the history that’s shaped the maternal health care folks experience now.

Her word of advice:

“Knowing where your resources are is so important because you might not get that list in the doctor’s office. So being willing, being willing to step outside of your comfort zone sometimes and ask for help. And hopefully, we can connect the dots for you.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the name of Dr. Sharla Smith.

Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS.