U.S. Army Base Renamed to Honor Black World War I Hero Kansas City Family Recalls Henry Johnson With Pride

Published February 22nd, 2024 at 6:00 AM

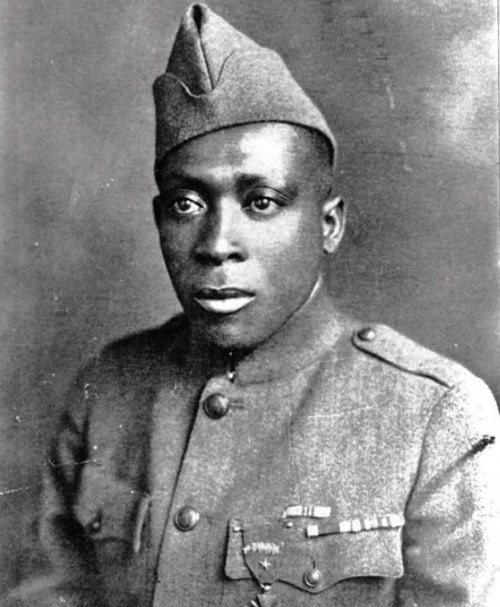

Above image credit: Before being assigned to combat duty, members of the 369th Infantry Regiment served largely as laborers after arriving in France in 1918. (Courtesy | National Archives)What once was a Louisiana U.S. Army base named for a Confederate general today bears the name of a Black World War I U.S. Army private.

It’s a complicated story that took more than a century to unfold, and there’s a Kansas City connection.

“This was beyond anything we expected,” said Tara Johnson, daughter of the late Herman Johnson, a Kansas City businessman and civil rights leader.

Herman Johnson worked for years to see the man he believed to be his father, World War I war hero Henry Johnson, receive formal acknowledgment for his fierce courage and resolve.

“Granddad’s honors have exceeded what we had hoped when our journey started,” Tara Johnson said.

Last summer Tara Johnson attended the renaming ceremonies in Louisiana. The rituals were part of the congressionally mandated directive, approved after the protests generated by the 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, to remove the names of Confederate figures from American military installations.

In 2023 Army officials renamed nine bases across the South, including the Louisiana base established in 1941 for Confederate Gen. Leonidas Polk.

“I went out early to hear the last gun salute under its previous name and later I heard the first gun salute after it became Fort Johnson,” Tara Johnson said of the Louisiana ceremony.

“It was very emotional, and very military.”

In 1918 Henry Johnson became one of the first American soldiers to receive the Croix de Guerre, or war cross, from the French government for his actions in fighting off a German raiding party and rescuing a comrade from being taken prisoner.

At the time Johnson, who grew up in Albany, New York, was serving in the 369th Infantry, an all-Black federalized New York National Guard unit otherwise known as the “Harlem Rattlers” or “Harlem Hellfighters,” which served under French command.

Johnson’s war cross included a gold palm leaf, representing the highest military decoration awarded by France.

The U.S. Army, meanwhile, never honored Johnson, who died in 1929.

Kansas City’s Herman Johnson long sought to correct that, collaborating for years with New York state politicians, researchers and veteran organizations.

The recognition eventually arrived, in increments.

In 1996 Henry Johnson posthumously received a Purple Heart, a medal recognizing those wounded or killed in combat. Johnson had suffered 21 wounds during his May 1918 night-time trench encounter.

In 2002 researchers confirmed that Henry Johnson had been buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Some confusion over the decades had occurred because some documents had listed the soldier’s name as William Henry Johnson.

Upon hearing that news Herman Johnson – who previously had been told by researchers that Henry Johnson may have been buried in an unmarked grave near Albany International Airport – travelled to Washington and stood with then-New York Gov. George Pataki at a wreath-laying ceremony.

In 2003 Henry Johnson posthumously received the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest military decoration that can be awarded to a member of the U.S. Army.

Herman Johnson accepted the cross during a Pentagon ceremony, and later that year spoke at an observance acknowledging the honor at what is now the National WWI Museum and Memorial.

“This was our country, and we were glad to fight for it,” said Herman Johnson, himself a veteran of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first Black flying unit in American history, serving during World War II.

“All we asked is that we be remembered and respected for it.”

Then, in 2015, Henry Johnson posthumously received the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest award for valor, during a White House ceremony.

“Henry was one of the first Americans to receive France’s highest award for valor,” President Barack Obama said.

“But his own nation didn’t award him anything – not even the Purple Heart, though he had been wounded 21 times.

“Not for his bravery, though he had saved a fellow soldier at great risk to himself.”

Tara Johnson attended the event, among other family members and U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri.

“The highlight on this whole journey was to hear our commander in chief tell the story of Henry Johnson like I’ve never heard anybody tell the story,” Tara Johnson told a reporter the following day.

There was, though, one problem.

Shortly before the White House ceremony, she met with an Army brigadier general representing the Army Past Conflict Reparations Branch, which had examined Henry Johnson’s life and combat record.

For recipients of the Medal of Honor, Army experts document blood relatives. But the genealogists could not confirm that Henry Johnson had been Herman Johnson’s father.

All his life, Tara Johnson said, her father had believed exactly that.

The Army said in a statement that it believed “this to be a case of historical inaccuracy, not fraudulent representation.”

Today the family mystery remains unexplained, Tara Johnson said.

Yet that did not stop, she added, Army officials in Louisiana from inviting her to the renaming ceremony at what is now officially the Joint Readiness Training Center and Fort Johnson.

The installation’s mission includes training combat teams “to conduct large scale operations on a decisive action battlefield against a near-peer threat with multi-domain capabilities.”

Tara Johnson thought that sounded right.

“During the ceremony, I thought of my grandfather, and I just thought, ‘Wow, these guys are training badasses,’” Tara Johnson said.

“What a fitting place to have your name.”

Some Chevrons, Some Medals

If the particulars of Henry Johnson’s personal life remain unclear, the details of his combat bravery are well documented.

Johnson worked as a train station porter before joining the 15th New York National Guard Regiment in 1917.

The federalized unit, known as the 369th Infantry Regiment, arrived in France in January 1918.

The African American members of the 369th first served as laborers until U.S. Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, agreed to the request of French military officials to allow them to fill a combat role on the Western Front.

On May 15, 1918, Johnson and a fellow private, Neadom Roberts, were on night sentry duty at a forward outpost in the Argonne Forest when they were ambushed by about two dozen German soldiers.

Johnson killed at least four of them and injured several others.

According to the Medal of Honor citation:

“Private Johnson exposed himself to grave danger by advancing from his position to engage an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and gravely wounded himself Private Johnson continued fighting and took his Bolo knife and stabbed it through an enemy soldier’s head. Displaying great courage, Private Johnson held back the enemy force until they retreated.”

As detailed in “Harlem’s Rattlers and the Great War: The Undaunted 369th Regiment and the African American Quest for Equality,” published in 2014, word of Henry Johnson’s actions spread quickly across the Atlantic.

New York newspaper accounts soon told of “The Battle of Henry Johnson.”

Many Americans had yet to read of American battlefield achievements in France, said Jeffrey Sammons, emeritus professor of history at New York University and the book’s co-author.

“You have to realize that this was not just about Henry Johnson being Black that made this special,” said Sammons.

“In my opinion Henry Johnson was the first infantry hero on the American side of the war. Johnson’s actions in May predated those of most American troops… Most Americans weren’t even over there yet.”

By contrast, the fame of Private – later Sergeant – Alvin York, another Medal of Honor recipient, spread after news of his gallantry in October 1918.

When the 369th Infantry returned to the United States the following February, it paraded down New York City’s Fifth Avenue, with Johnson standing in an open car holding a bouquet of lilies.

“Henry was the star of the parade, the one everyone had heard about,” Sammons said.

The parade prompted praise from the New York press, with some editorial board members wondering if full equality remained within reach in a rigidly segregated America.

Still, some of the same newspapers undermined the moment with reporting that indulged in stereotypes. Further, the New York World, Sammons said, seemed to resent how Johnson – whose injuries prevented him from marching – had ridden in the open car.

The New York Tribune, meanwhile, printed a faux scorecard, making light of the number of German casualties attributed to Johnson, separating those whom Johnson had “Scared to Death” from those he allegedly had “Kicked and Cussed Out” during the savage trench encounter.

“The press was all over him for standing in an open vehicle, but also about just how many Germans he had killed,” Sammons said,

The Army, in turn, displayed indifference to Johnson’s postwar prospects, Sammons added.

French doctors, treating Johnson’s injuries, had removed many bones in one of his feet and replaced a shattered shinbone with a silver tube. He would not be able to return to his civilian job as a porter.

Yet when the Army discharged Johnson in February, according to “Harlem’s Rattlers and the Great War,” officers judged him “zero percent disabled,” following what appears to have been a systematic effort to keep members of the 369th Infantry below the threshold for benefit eligibility.

The military’s lack of recognition had a profound negative effect on Johnson’s personal postwar transition, Sammons said. While Johnson received a promotion to sergeant, along with the requisite additional stripes for his uniform sleeve, he did not receive proportional medical benefits or compensation.

“People don’t understand how the lack of recognition really weighed upon those who sacrificed while performing such heroic acts,” Sammons added. “Any recognition at all could have opened all kinds of opportunities to him.”

But, Sammons said, “the only thing he got was some chevrons and some marksmen medals.”

Henry Johnson’s postwar fame proved ephemeral. While he went on a brief speaking tour, some audiences were angered by his candid descriptions of his regiment’s experiences in the segregated U.S. Army.

Johnson’s last public appearance was in 1919. After that, little documentation exists regarding his activities.

In 1929 he died of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, leaving a wife and three children.

Blindsided

Herman Johnson of Kansas City, meanwhile, always believed he was Henry Johnson’s son.

The younger Johnson, born in 1918 in Schenectady, New York, was reared by an uncle in Elmira from about age 6, Tara Johnson said.

“His uncle was an entrepreneur and owned several stores. That’s where Dad got his business and finance savvy from.”

After serving in World War II, Herman Johnson earned bachelor’s and graduate degrees from Cornell University and the University of Chicago. He went on to direct the Howard University Medical School teaching hospital in Washington, D.C., and then served as a district manager for an insurance company in Ohio before moving to Kansas City in the late 1950s.

Herman Johnson twice led the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and served two consecutive terms in the Missouri House of Representatives beginning in the late 1960s.

Over the years he operated his own insurance and real estate firm from an office near Ninth Street and Baltimore Avenue. He also owned and operated Lincoln Cemetery, a historic Black burying ground today known as the final resting place of Kansas City jazz legend Charlie Parker.

He was a constant participant in Kansas City civic life, serving on boards for the United Way, the Chamber of Commerce of Greater Kansas City, Rockhurst College and the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

He died in 2004 at age 87.

Today a bridge at 27th Street and the Paseo bears his name. The University of Missouri-Kansas City also named a residence hall after Herman and his late wife Dorothy Hodge Johnson.

And for all his adult life, Tara Johnson said, her father believed Henry Johnson was his father, telling detailed stories of how he often visited him as a child.

Not surprisingly, the U.S. Army’s 2015 revelation blindsided her and her family.

The general showed her several documents, among them her father’s birth certificate and her grandmother’s marriage license.

On neither of the documents did the name of the World War I hero appear.

No additional evidence has surfaced since then to explain the mystery, Tara Johnson said this month.

“Dad is not here to tell me how all this may have happened,” she added.

But given that Army officials reached out to her to attend the Louisiana ceremony last summer, she said, she believes the lack of documentation matters little.

“I am fine with it now,” she said.

“Herman Johnson was still my dad, and Henry Johnson was still my grandfather, and life is going to go on.”

Actions that Transcend Time

The honors to Henry Johnson, meanwhile, continue.

In January Army officials at the newly named Fort Johnson unveiled a new monument to the base’s namesake.

“We pay tribute to a man whose actions transcend time and whose spirit of bravery will forever be etched in our hearts,” Fort Johnson’s commander, Brig. Gen. David Gardner, said during the ceremony.

“Of course, this doesn’t do anything for Henry except for his memory and legacy,” Sammons said.

“But it certainly is a source of pride and consolation, that a camp that once was named for a Confederate general now will bear the name of the most famous and acclaimed Black soldier in World War I, who was denied the accolades and awards that he deserved.”

Others agree.

“The history of the Harlem Hellfighters is so rich,” Brig. Gen. Isabel R. Smith, director of joint staff for the New York National Guard, said recently from Guard headquarters in Latham, New York, an Albany suburb.

Smith attended the Fort Johnson renaming ceremonies and visited there with Michelle Howard, a retired U.S. Navy four-star admiral who served on the committee that selected the new names for the Army bases.

While there had been many submissions and suggestions as to which historical figures should be considered, Howard told Smith that the Henry Johnson story had been found especially compelling by committee members.

“Obviously, the U.S. Army was not integrated back then, and considering how many years it took for this to happen, we are excited by the recognition,” Smith said.

“This is important to me and my colleagues. This is something we can pass down to our children.”

Henry Johnson’s story continues to resonate in contemporary culture, in unexpected ways.

In 2021 a Ukrainian rock band named 1914, whose music is often described as “doom” or “death” metal, released the album “Where Fear and Weapons Meet.”

Among its songs is “Don’t Tread on Me (Harlem Hellfighters),” which presents Johnson’s actions in the trenches as if described by the soldier himself, in some cases using quotes attributed to him.

“The only weapon left is my Bolo knife/

So I climbed up from the ground and charged/

Hacking away at the foes…

There wasn’t anything so fine about it.

Just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.”

Tara Johnson’s recent trip to Louisiana, meanwhile, convinced her that Henry Johnson’s story still could command the attention of everyday Americans.

For years she has presented commemorative coins to those who have worked to maintain the memory of Henry Johnson’s sacrifice.

For the renaming ceremony last summer, she ordered a new supply of those coins.

But a post office snafu threatened to make the coins unavailable during the ceremony.

She drove to the post office that morning to find it closed. Anxious, she waved down an employee who came out and – upon hearing her story – went back in, found the coins, and brought them back out.

“He said to me: ‘You know what? I trained over there. And it’s about time.’ And this was a white man. He got it. He understood.

“My grandfather went over there and fought for his country, not to be recognized as a Black man, but to be recognized as a man.”

“I handed that man coins for each person in that post office.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016.