curiousKC | Kansas City’s Crossroads has a Historic Tie to Hollywood A Former Home to ‘Film Row’

Published June 6th, 2022 at 12:59 PM

Above image credit: A Warner Brothers building located along Kansas City’s Film Row. (“Fade to Black” | Kansas City PBS)During the golden age of cinema, moviegoers faced no shortage of options when it came to where to settle in for an evening in front of the silver screen.

The 1941 Film Daily Year Book reported approximately one movie theater for every 8,000 persons in the United States.

The same year the United States entered World War II, the U.S. population was just shy of 133.5 million. Considering the demand for entertainment before television and sparing even quick math — that’s a lot of theaters and tons of film.

During the 1920s movie boom, it’s estimated that about 800 films were produced annually in the United States. The figure includes cartoons, news reels and media outside of feature pictures that also were shown in theaters across the country.

Just one movie may have required six to 10 reels of film.

The sheer scope of commercial film production during its height and massive demand from audiences is the short answer to a recent inquiry from a Crossroads Arts District-based Kansas Citian and curiousKC follower, who wanted to know more about their neighborhood’s historic ties to Hollywood.

“Why did Hollywood use the Crossroads as a space to store their film?”

Long before First Fridays became a thing, the modern-day Crossroads served as home to Kansas City’s own Film Row.

As movie production soared and theaters remained packed with patrons, studios in Hollywood and New York made even more movies.

The boom called for a network of film distribution, so-called “exchange centers” where reels from studios like MGM, Walt Disney and Warner Brothers could be stored and distributed to theaters around the country.

Film Row in the Crossroads

Between the 1920s and 1970s, film studios looked to an old friend of the industry in Kansas City to serve as an essential arm of Hollywood and more broadly the evolving entertainment industry. Smack in the middle of the country, blessed with a robust railroad hub, Mickey Mouse’s hometown made a lot of sense.

KC’s Place in Film Exhibition

To better understand the function of the nationwide network of some 30 film rows and all of the logistics that came with film distribution back in the day, Flatland phoned Dr. Derek Long, an assistant professor of media and film studies at the University of Illinois.

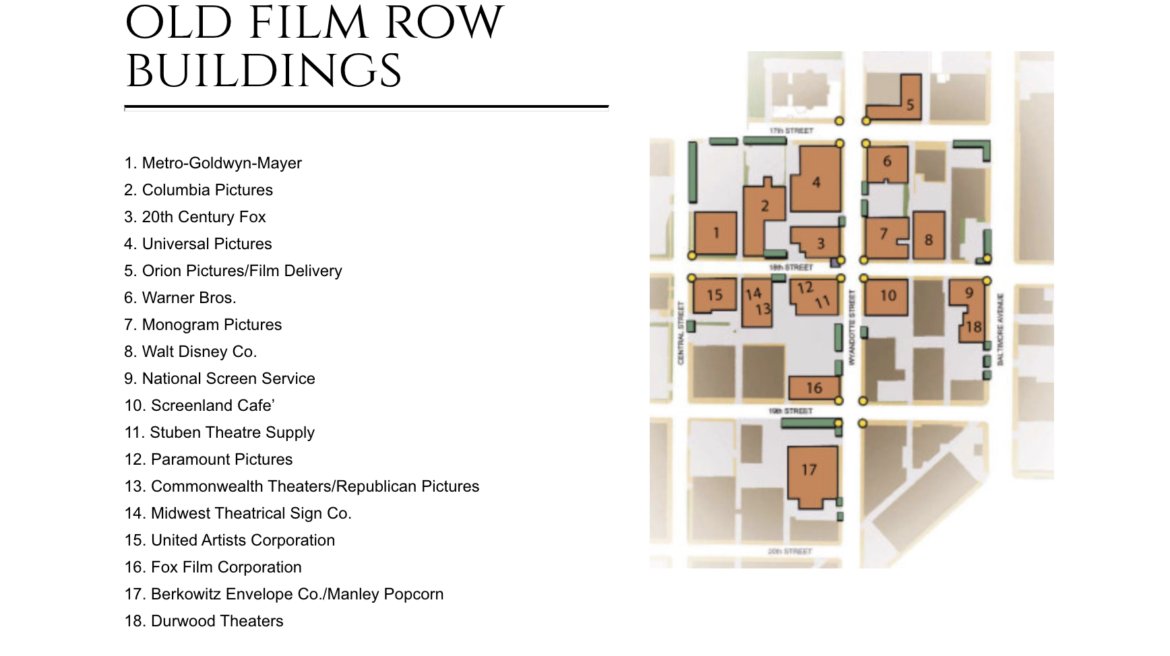

While the overarching purpose of film rows during this time was rather boring and “workaday,” according to Long, raising the curtain on the essential role of the 15 or so local buildings, many of which still stand in the Crossroads, reveals the major part that Kansas City played in the immense post-production effort to ensure big screens were brought to life in theaters across the region.

“In terms of the sheer numbers of films the film rows were storing, it’s really quite extraordinary. They were making a lot more movies in the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s than are made now,” Long said.

Back then, film was stored in large, heavy canisters and was most often transported by train. With hundreds of movies and other films made annually, each made up of multiple reels — plenty of physical storage space was a must.

Once a movie was completed and it was time to send copies of the film from most likely New York or Los Angeles to Midwest markets, the reels were shipped to a designated storage space on Film Row.

Kansas City’s part in the process would have been delayed by just a hair in the days before simultaneous movie premiers. Major markets like Philadelphia, New York or Chicago would likely see Hollywood’s latest picture before the rest of the country.

Centrally located, Kansas City’s Film Row served as storage space for thousands of canisters of film that could then be sent to theaters in the the surrounding region, plus marketing materials and other industry office odds and ends.

As for Film Row’s physical location in the few-block radius between 17th and 19th streets downtown, the organization of dedicated buildings in close proximity came as part of a wave of city ordinances adjusting to the changing technology, centered on safety.

If you’ve seen the pyrotechnic climax of “Inglourious Basterds” (2009), the need for safe film storage makes a lot of sense.

“Before there were film rows, each company had its own sort-of pop-up office,” Long said. These unregulated spaces did not pair well with sometimes-thousands of pre-1950s highly-flammable nitro cellulose reels stacked to the ceiling.

“Basically, the local exchange areas passed municipal laws saying that all film distribution has to happen in these film rows where there are controlled laws, laws about how you build the building, how you fireproof it, all of that stuff,” Long said.

Outside of safe storage space, film rows also served as a place for local theater runners to see pre-screenings of films.

Business between theater owners and distributors would have been done over Kansas City’s first-ever private screenings of classics like “King Kong” (1933), “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946) or any number of productions represented at the exchange space.

If a popular local theater runner enjoyed a film and picked it to be shown in the Kansas City market, the thinking was that small town and rural theaters would soon follow suit.

Staying on top of the films flowing through Kansas City would have been especially important for rural theater owners. After all, there’s no reason the repetitive nature of rural living should spill into the simple pleasure of the movie theater. Especially if the nearest big screen was a few towns over.

“Back in those days, if you’re in a small theater, you might change the bill every day,” Long noted.

Finally, film rows served as a contact point for theaters with damaged reels. Back then, sending equipment from Ottawa to Kansas City for repairs was considered as convenient as online troubleshooting is today.

Fall of Film Row

The way theaters receive and screen movies hasn’t changed entirely.

At the midnight premiere of the next Marvel movie, chances are the theater will still receive a physical version of the film. In place of six to 10 heavy and potentially deadly film canisters shipped hundreds of miles by railroad, a Digital Cinema Package hard drive can be shipped to an individual theater by mail, perhaps overnight.

There is, however, no need for film rows in 2022.

Just as advancements in technology and changing consumer habits called for the rapid creation and expansion of film rows, industry changes made the method of distribution obsolete by the 1970s.

“My sense is that it was probably the rise of home video,” Long said, considering factors that led to the fall of film rows.

In addition to consumers eventually being able to watch movies at home, not to mention the rise in television’s popularity, movies on tape changed how theater owners could pre-screen films ahead of taking tickets. There was no need to travel to Kansas City for a first peek on film row.

As time went on, the space needed to store physical film shrank. Shipping methods shifted away from the railroad. By the 1950s, film was made from less-flammable acetate, so the means of shipping and storing film became significantly less dangerous and a more durable product.

Industry adaptations in distribution also played a major part in the operational overhaul.

“Instead of having this kind of staggered, windowed release where a film starts in New York and Chicago and Philadelphia before then it goes to neighborhood theaters and then it goes to rural theaters, in the 1970s, you started to have saturation booking,” Long said.

“Films premiered on the same day, across theaters everywhere in the country.”

Flatland contributor Clarence Dennis also is a social media manager for 90.9 The Bridge.