Blue Springs is Latest Battleground For Education Program Flash Points Include Financing, Classroom Discipline

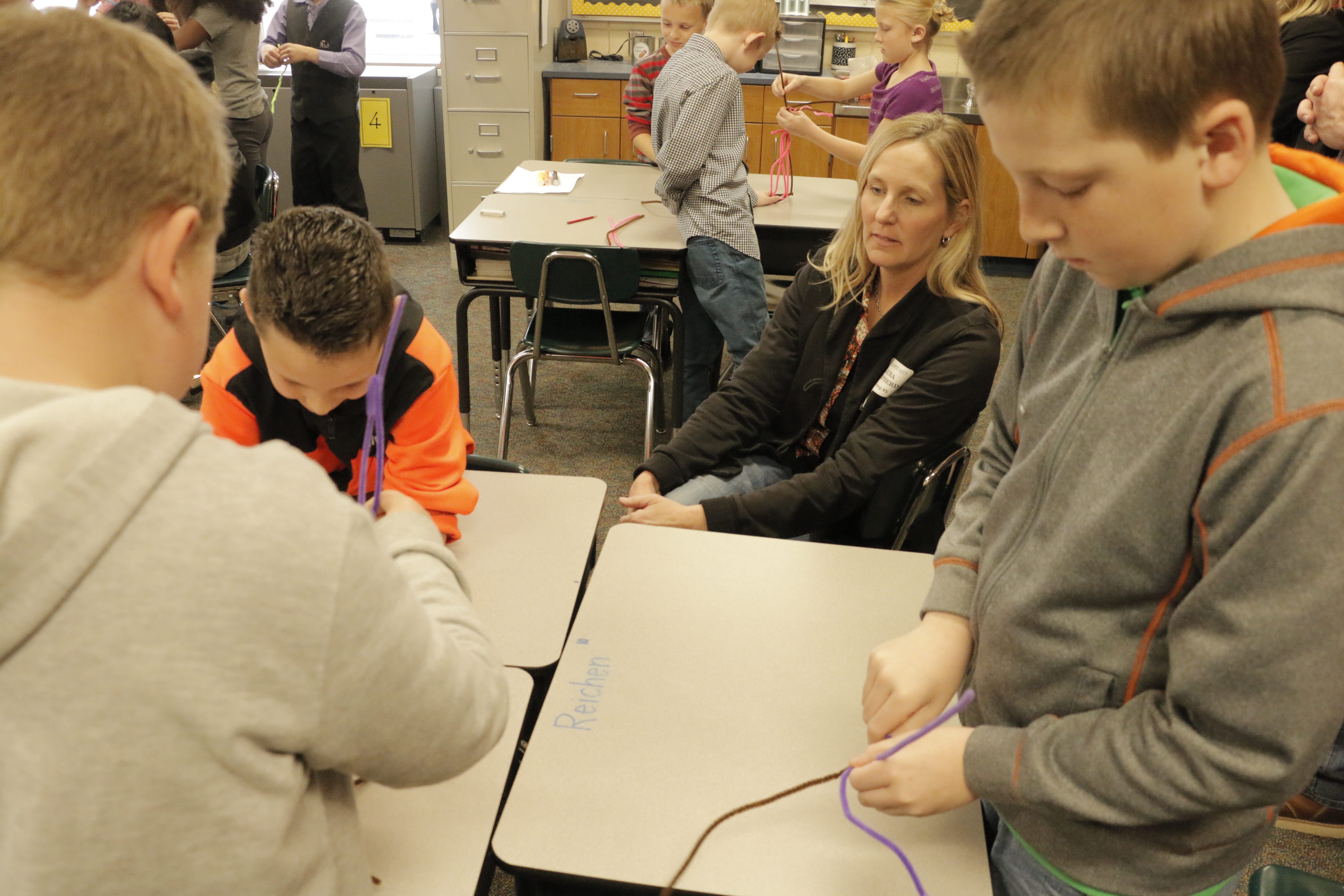

Students at Franklin Smith Elementary in Blue Springs, Mo., welcomed visitors to "Leadership Day" in March. The event showcased "The Leader in Me" program, which has sparked controversy at the school and in various other communities in the U.S., abroad, and online. (Photo: Mike Sherry | Flatland)

Students at Franklin Smith Elementary in Blue Springs, Mo., welcomed visitors to "Leadership Day" in March. The event showcased "The Leader in Me" program, which has sparked controversy at the school and in various other communities in the U.S., abroad, and online. (Photo: Mike Sherry | Flatland)

Published May 12th, 2016 at 2:45 PM

Laura Shepherd loved it when the kids entering Franklin Smith Elementary got a morning hug from the principal. But that was last year.

This year, Shepherd hated watching building leaders at the Blue Springs, Missouri, school greet her fourth-grader and other students with handshakes.

“I’m like, ‘They are not mini-adults. They are kids,’” she said. “That made me sad, made me sick to sit there and watch it.”

What’s prompting her ire is The Leader in Me, a character-based program adapted from Stephen Covey’s influential self-help book “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”

Jump to Section

Praise for the Program

‘Something Sneaky’

Beyond the Money

Searching for Success

Critics like Shepherd argue Franklin Smith is wasting money, indoctrinating students and sacrificing classroom discipline for a program they contend is aimed at enriching a for-profit company. They also argued the program unduly influences building leaders through well-paid consulting jobs.

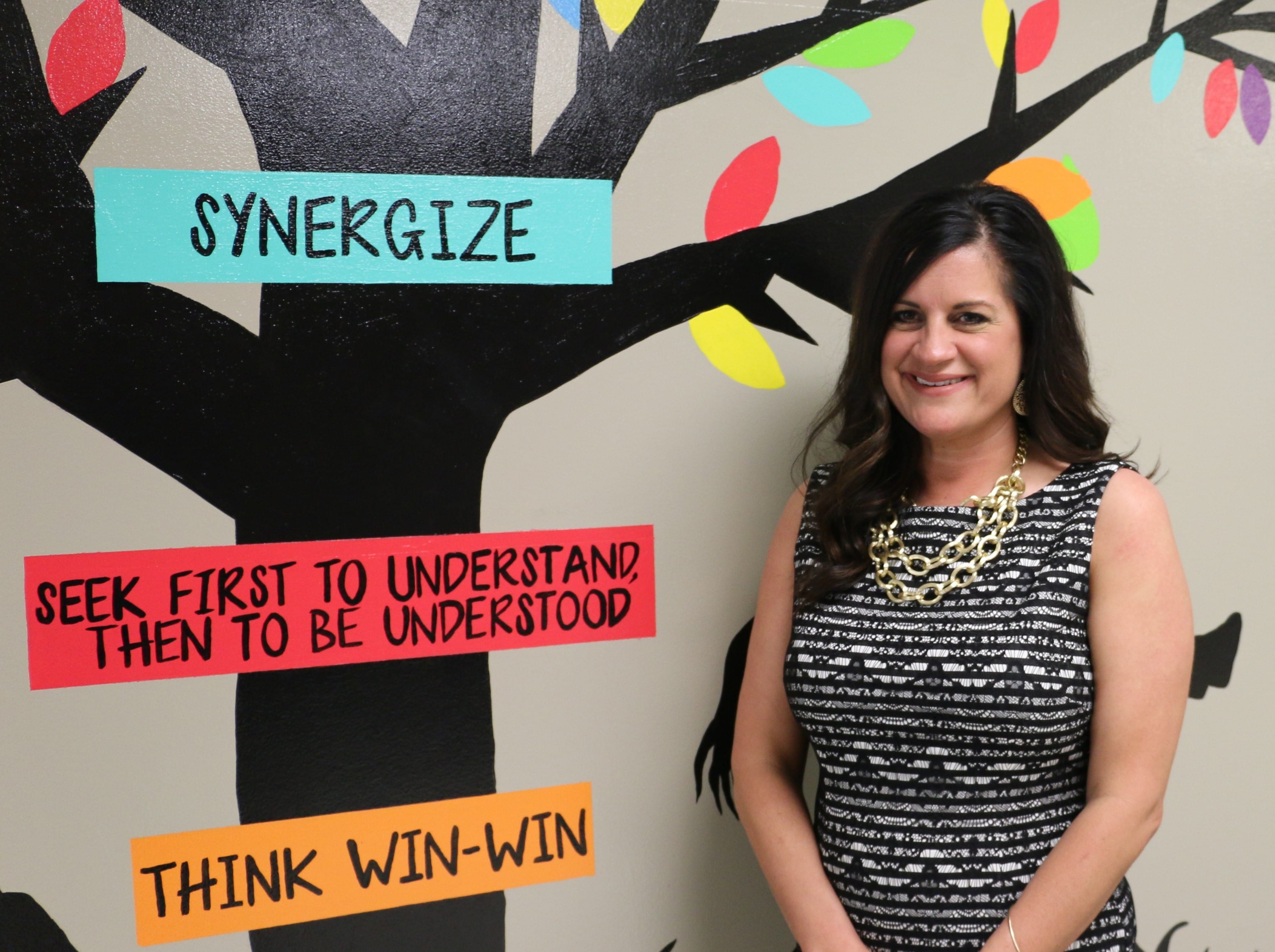

Disgruntled parents and staff have pinned much of the blame on the school’s new principal, Ramona Dunn, even though her predecessor OK’d the program. Dunn’s critics contend she rammed through Leader in Me at Franklin Smith.

Dunn said the antipathy at Franklin Smith is similar to the frustrations she overcame among staff when implementing Leader in Me at William Yates, the district elementary school she led before transferring. The four-year history at William Yates provides the most detailed track record of Leader in Me in the district.

“We are learning this process together,” Dunn said, “and so it’s still early, it’s too early.”

“7 Habits” has been an international best-seller since it was first published in 1989. The idea for Leader in Me emerged a decade later when a North Carolina principal applied Covey’s principles to her struggling school.

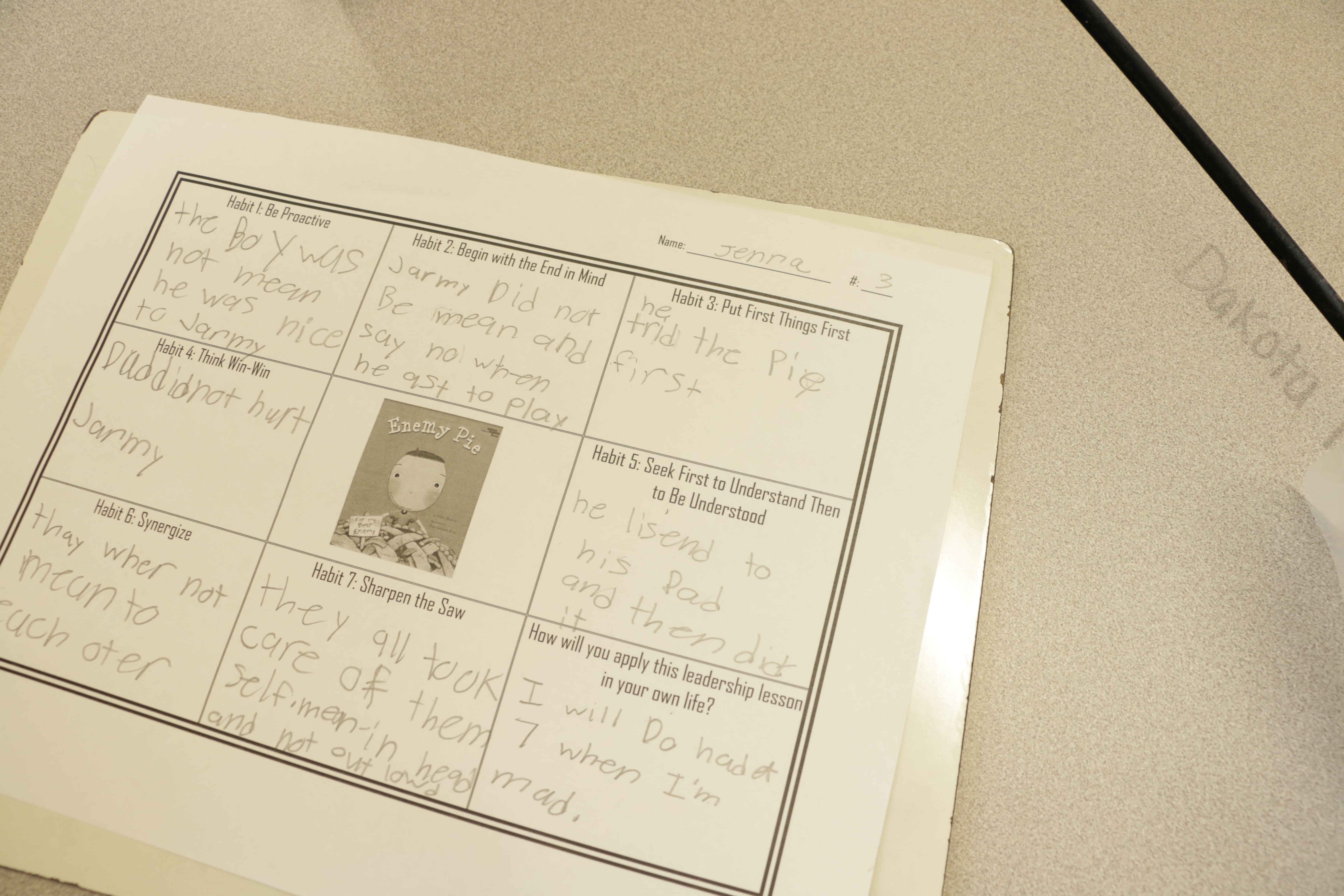

The program is promoted as a “whole-school transformation process that integrates principles of leadership and effectiveness into school curriculum using everyday, age-appropriate language.”

In adopting the Covey habits, the program teaches students to “Sharpen the Saw,” meaning taking time to recharge so they can accomplish their tasks. Students also are urged to “Synergize,” or work together as a team, and to “Put First Things First” to avoid procrastination.

The number of Leader in Me schools has increased from six in 2008 to more than 2,500 worldwide today, including nearly two dozen in the Kansas City metropolitan area. The program is in three Blue Springs schools, and at least a couple more are looking into it.

“Anyone who goes along with this ridiculous program has rocks for brains.” –blog comment about The Leader in Me program

Ironically, a program designed to encourage cordiality has sparked outright hostility around the country and even overseas.

Closer to home, at Franklin Smith, virtually the entire PTA executive board resigned May 5 to protest Shepherd’s ouster as treasurer, an action they perceived as retaliation for complaints she filed with the state about implementation of Leader in Me at Franklin Smith.

Called into Dunn’s office at the end of the meeting by Sherri Haupt, president of the district-wide PTA council, Shepherd refused the offer to resign and forced a vote of no confidence. Shepherd rejected charges that she had not been transparent with the books, was not there for children and parents, and that she talked down to people.

In a follow-up email, Haupt said two of the executive board members that resigned are being allowed to finish their terms, as per their requests. Her email did not address the accusation that Shepherd was removed because of her opposition to Leader in Me.

Haupt also said the district PTA council has hired an outside auditor to review the books of the Franklin Smith chapter, in accordance with bylaws covering the removal of the treasurer.

The proceedings blindsided Shepherd, but Haupt’s visit was actually the second time this spring that a PTA higher-up surprised some members of the the Franklin Smith chapter.

Michele Reed, a leader with the state PTA, showed up at the board’s March meeting.

Reed had the Franklin Smith PTA president, Meg Swant, sign a letter rescinding complaints the school’s executive board had filed with the Missouri Ethics Commission and the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Reed told them they had violated protocol by representing the organization without approval from the members.

Haupt said that Swant has requested the presence of outside PTA executives at the Franklin Smith meetings.

Board members said they appealed to the state after exhausting remedies at the local level, including outlining their concerns in an eight-page letter to the central office and having what they considered to be an unproductive follow-up meeting in February.

“I don’t think we have blown them off,” Deputy Superintendent Annette Seago said. “I think we are pretty solid and responsive in getting back to people.”

The Franklin Smith opponents share the concerns expressed elsewhere:

- Parents and teachers in Stockholm, Sweden, protested against the program in 2013 as a one-size-fits-all approach that focused too much on productivity and used language that was too advanced for younger children.

- Three years ago, in Redmond, Washington, parents got the program kicked out of their elementary school amidst complaints that it was a solution in search of a problem, it wasn’t properly vetted as curriculum, and that proponents antagonized people who questioned the program.

- Critics have vented on the Web through outlets like a blog titled “The Leader in Me: Too Good To Be True?” and the Say NO to “The Leader in Me’” Facebook page, which describes the program as “corporate indoctrination with religious concepts posing as character and leadership education.” Covey was a devout Mormon.

Education blogger Jennifer Gonzalez has written that no topic on her site has matched the fervor surrounding Leader in Me. Her post summarizes the six main objections commenters have raised about the program, including excessive cost and questionable educational value.

That post continues to spark impassioned debate a year and a half after it was published.

“Anyone who goes along with this ridiculous program has rocks for brains,” said one post from last month.

“I don’t understand how you could be opposed to something that makes your kids excited about going to school.” –Blue Springs parent, Diana Latlip, on The Leader in Me

At Franklin Smith, the PTA complaints have prompted changes.

The ethics complaint centered around Dunn’s work as a part-time, paid consultant for FranklinCovey, where she assisted schools in other districts implementing Leader in Me.

The ethics commission found no problems with Dunn’s work for FranklinCovey, but she recently quit, saying that the summer work infringed on family obligations and that it was a distraction from her work at Franklin Smith.

Dunn declined to comment on how much she earned through the job, but a Lexington principal told education authorities in Kentucky that he earned $2,500 per day plus travel expenses as a Leader in Me trainer. FranklinCovey said these consultants sometimes work as many as 20 days a year.

Differing from Missouri regulators, Kentucky’s Office of Education Accountability (OEA) found the principal’s work unethical and required him and district leaders to undergo conflict-of-interest training.

FranklinCovey argued to Flatland that education companies commonly use school personnel as salespeople for textbooks and other products.

At Franklin Smith, PTA leaders also persuaded the school to scale back the “Leadership Day” it had scheduled for mid-February. The event was tied to a regional Leader in Me symposium in Kansas City.

PTA leaders argued it violated district policies by not performing background checks on outside visitors and allowing third-party observation of students.

In addition, they said in the letter to administrators, it appeared their children were being “exploited as involuntary salespeople for FranklinCovey.” The I Am A Leader Foundation requires grantees to have such events annually to “showcase the school’s leadership work.”

Praise for the Program

Franklin Smith rescheduled the event to late March and limited attendance to family members, including Michelle Worley.

She told the crowd she was bullied as a kid and described how the handshakes and purposeful eye contact at Franklin Smith quickly allayed her fears that history would repeat itself when her son entered kindergarten this year.

She argued that Leader in Me starts students on a path to becoming good citizens and develops the leadership skills each child possesses.

“If we can find that leader, we can develop that leader, and if we develop that leader, then they will believe in themselves,” Worley said, “and if they believe, they will do, and if they do, they will change this world. And I believe this world could use a little changing.”

Dunn also left behind some happy parents at William Yates, including Diana Latlip, the mother of three boys.

Latlip marveled at how her youngest son blossomed into a look-you-in-the-eye second-grader through Leader in Me, and she thought it was “cool” how her oldest son noticed a calmer, happier atmosphere at the school than when he attended there.

Latlip considered Leadership Day a chance for students to shine, and she was proud that FranklinCovey thought enough of Dunn to make her a consultant.

As for the opposition at Franklin Smith, she said, “I don’t understand how you could be opposed to something that makes your kids excited about going to school.”

‘Something Sneaky’

One reason for the skepticism at Franklin Smith is the fact that Leader in Me is intertwined with both FranklinCovey Co., a worldwide, for-profit training and consulting company, and the nonprofit I Am a Leader Foundation. The organizations are headquartered about 40 miles apart, respectively, in the Utah communities of Salt Lake City and Provo.

Covey’s son, Sean, leads the Education practice at FranklinCovey, which includes Leader in Me. The head of the foundation is Boyd Craig, a longtime business partner of Stephen Covey.

According to the company’s 2015 annual report, Leader in Me has helped make the Education practice one of the company’s fastest-growing divisions. The practice had revenue of $32.5 million last year, about 15 percent of the company’s total revenue.

Discounts given to education clients reduce sales earnings, according to the company.

Franklin Smith is similar to many Leader in Me schools in that it received a three-year grant of approximately $44,000 from the foundation, which goes directly to FranklinCovey for Leader in Me materials and consulting.

The grant agreement also requires Franklin Smith to spend more than $33,000 of its own money on FranklinCovey coaching services and licensing fees. The company says those “sustainment core” fees are meant to solidify schools’ long-term commitment to the program.

But that building-level spending has raised a number of concerns among critics in Blue Springs, including an anonymous letter from a teacher objecting to spending $1,200 from the Franklin Smith supply budget.

Those opponents also have argued that Leader in Me’s emphasis on using Title 1 funding smacks of a money grab from a $14 billion federal program targeted toward low-income students.

And finally, skeptics share concerns raised in the Kentucky case, where the principal did not account for thousands of dollars the school raised and spent on the program. In Blue Springs, for instance, documentation at William Yates accounts for only about 40 percent of the non-Title 1 spending on Leader in Me, or about $16,000.

Samantha Kuykendall has friends at William Yates who love the program, but at Franklin Smith, she said some parents and teachers don’t feel as informed about the intent and purpose of fundraisers for Leader in Me.

“It feels like something sneaky is going on underneath the surface,” said Kuykendall, one of the Franklin Smith executive board members who resigned last week.

Dunn conceded that she might have rushed implementation at Franklin Smith because of the success of Leader in Me at William Yates. But she said the program already has proved its worth at her new school.

Dunn recounted overhearing a student on her way deliver morning announcements over the intercom — part of her Leader in Me job — tell her friend that it was the highlight of her day.

“The energy that she had right then and there, the excitement that she had coming to school, on a Monday, a week before spring break,” Dunn said, “she is going to take that back to her classroom and be a learner, and that energy is going to spread to her friends.”

Beyond the Money

Leader in Me grantees must meet certain benchmarks to continue receiving funding from I Am A Leader. Those criteria include increasing attendance rates and decreasing office referrals.

Franklin Smith parents Brandi Crawford and Jennifer Skoviak argued that the pursuit of those goals caused problems.

Crawford said there is a double standard when it comes to teacher absences for Leader in Me training. “They are focusing so much on attendance,” she said, “but the teacher has missed more days than my kid.”

It also appears to them that teachers are reluctant to send disruptive students to the office, relying instead on the school resource officer (SRO) as a surrogate disciplinarian for staff. SROs are police officers at schools largely to serve as a trusted figure for students

Skoviak said her first-grade son and his friends are scared to see the SRO coming because she is the one who “gets the kids when they are bad.”

“We see that these kids are coming to school with less, and not just less money, but other skills as well.” — Meg Thompson, general manager of FranklinCovey’s education practice

The district rejects the suggestion that the program influences school policies.

For instance, even though office referrals at William Yates dropped from 72 to 17 the year Dunn implemented Leader in Me, and then fell to zero the next year, Dunn attributed the drop to her management style.

Searching for Success

Leader in Me grantees are also expected to improve math and reading skills — gauged by the percentage of students meeting grade-level expectations.

At William Yates, students did make strides in proficiency in math and reading on the Missouri state exam after implementation of Leader in Me, but the school slipped in the percentage of students scoring at the advanced level in these subjects.

Dunn said other assessments have shown academic growth in areas such as reading fluency.

FranklinCovey has faced questions about the legitimacy of research it cites to bolster its claims of academic success. One of those skeptics is Judith Fonzi, a professor in the Warner School of Education at the University of Rochester in New York.

She reviewed evaluations of the program in 2011, when FranklinCovey requested she endorse the program to the Rochester City School District. She declined, determining there was “no real rigorous scientific research” to back up any claims of success.

This is one reason critics locally and nationally question the use of Title 1 funds for the program, arguing that poor students would be better served with help on core subjects rather than on the soft skills emphasized in Leader in Me.

This shortcoming is not limited to this particular program, Fonzi said.

“A glitch in the system,” she said, “is that Title 1, and many other programs, don’t check, don’t know and apparently don’t care how the money is spent.”

Leader in Me schools in Blue Springs, along with most of the others in the metropolitan area, are Title 1 schools, meaning at least 40 percent of the students are poor enough to qualify for free- or reduced-price lunches.

Meg Thompson, general manager of FranklinCovey’s education practice, contended that so many of its participants are Title 1 because these schools are inherently needy.

“We see that these kids are coming to school with less, and not just less money, but other skills as well,” she said.“We look at these kids and think they need all of the help they can get, and we hope the program is giving them something extra.”

Dunn is less concerned with research and more focused on what she has seen on the ground in her schools.

“The kids are going home and working first and not having fights with their parents about doing their homework,” Dunn said. “They are learning the value of putting work first, and then what is happening, their grades are improving, their homework is getting done like it’s supposed to.”

— Mike Sherry covers health and education for the Hale Center for Journalism. He can be reached at 816-398-4205 or at msherry@kcpt.org.

— Tammy Worth is a freelance journalist based in Blue Springs, Missouri. She is a Franklin Smith parent and former board member of the school’s PTA. None of Worth’s work involved the PTA or the Blue Springs School District.