A Solution for Economic Problems: Hire More Immigrants Challenge is Fixing a 'Broken' System

Published January 19th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: A view of Kansas City's skyline. (Brad Austin | Flatland)Two Kansas City economists sit down to talk business.

They discuss the area’s unusually low unemployment rate (2.6%) and the possibility of a recession in 2023 (expect a mild one).

But within minutes, Frank Lenk and Chris Kuehl turn to where their conversations inevitably go.

The United States, and Kansas City even more so, have worsening labor shortage problems.

Put simply, there are not enough qualified workers to fill open jobs in many industries, the economists said during a recent session organized by the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce.

There simply aren’t enough workers, period.

Moreover, the situation is not going to get better anytime soon, thanks to a demographic wave of retiring baby boomers who were born between 1946 and 1964.

“By 2030, all of the boomers will reach retirement age,” said Kuehl, managing director of Armada Corporate Intelligence. “All of them, 73 million coming out of the workforce.”

This, Kuehl likes to emphasize, should not have been a surprise.

“When junior was born, you knew when junior was going to hit retirement,” he said. “You just had to add 65 years.”

The lack of policy focus on that reality is stunning to Kuehl, considering the potential impact on the economy, inflation and the ability of the nation to compete globally.

“Did we prepare for it? No, we did not,” he said. “And there’s not a lot of easy ways to replace that workforce.”

Like Kuehl, other economists, business professionals and labor experts all concur on one answer: Hire more immigrants.

His counterpart, Lenk, chooses one word to describe the role of immigration in the labor market: “Critical.”

“When junior was born, you knew when junior was going to hit retirement. You just had to add 65 years.”

Chris Kuehl, managing director of Armada Corporate Intelligence

At the end of each calendar year, Lenk prepares an economic forecast for the year ahead as director of research services at the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC).

“Immigration is critical to a well-functioning economy,” Lenk said. “It’s one of America’s strengths, compared to Europe. Historically, we’ve been more welcoming of a large number of immigrants, but that’s changed in the last several years. It’s constricting our growth.”

Kuehl makes another point, showing how the situation has shifted from past generations, when immigrant labor often filled roles at the lower end of the U.S. wage scale.

Then, the need was for manual labor, often referred to as the jobs that many native-born people don’t want to fill.

Labor needs are different now.

“The immigrant that we need is a more trained, more educated, more skilled immigrant and we’re competing with every other country in the world for that same worker,” Kuehl said.

Flatland on YouTube

Inside a ‘Broken’ System

We hear about the “broken” immigration system so much that it has become a cliché, referenced by politicians and business leaders alike.

Many see the need for a nimble process, one that reacts to changing labor needs in various industries.

That is not the system that we currently have, a fact that corporations discover when they try to hire highly skilled immigrant employees.

The Overland Park firm of Mdivani Corporate Immigration Law Firm is often where firms turn next. Mira Mdivani, a business immigration lawyer, founded it.

Her firm helps companies to legally hire immigrants, helping them manage the wide array of complicated paperwork involved.

Mdivani clicks through a rough outline of the types of industries and workers her clients need.

For a grain operation, a business would need an agronomist. A small farm might need a veterinarian. Hospitals need medical technologists. Transportation companies need people with degrees in logistics. Financial institutions need people with degrees in mathematics. Engineers, especially civil and structural, are in high demand.

“And all businesses across the board need people for software development with degrees in computer science or a related field,” she said.

For example, the KC Tech Council reports that there were more than 27,000 tech job postings in 2021 in the region and not nearly enough local talent to fill the spots.

Moreover, the council predicts that Kansas City will need to replace about 3,733 tech positions annually due to retirements, workers shifting to other roles or simply leaving the profession.

Invariably, some of those positions might be filled by immigrant workers.

What employers try to navigate when sponsoring an immigrant for employment is basically a lottery system.

A congressionally set cap of 85,000 is allotted every year for higher-skilled immigrants to be sponsored by an employer for permission to live and work in the U.S.

But the demand far outstrips the available slots.

Last year, nearly 500,000 requests were filed by employers, said Danielle Atchison, a business immigration attorney with Mdivani.

“These are jobs in technology, or these can be doctors, scientists all sorts of pretty high-paying jobs that will go elsewhere,” Atchison said.

Employers also must prove that no available native-born person can fill the role, a measure for protecting U.S. employment.

The entire process can cost an employer up to $15,000, including governmental fees.

Many of the people that companies want to hire were educated as foreign students at U.S. universities, Mdivani said.

“We’re lucky that we have foreign students here and foreign professionals that want to stay in the U.S.,” Mdivani said.

Mdivani also is president of the Corporate Immigration Compliance Institute.

She notes how easily conversations derail when the topic is workers and immigration.

“Those issues … on the left and on the right have basically killed the prospects of seeing it as a total economic issue and resolving it as, ‘What does our country need as an economy, as a prosperous economy?’ It’s a discussion based on raw emotions, not based on fact.”

Mira Mdivani, Mdivani Corporate Immigration Law Firm

She finds culprits at both ends of the political spectrum. Scapegoating and misinformation are common.

On the left, she said they focus on exploitation. On the right, it’s an accusation about stealing U.S. jobs.

“Those issues … on the left and on the right have basically killed the prospects of seeing it as a total economic issue and resolving it as, ‘What does our country need as an economy, as a prosperous economy?’ ” Mdivani said.

“It’s a discussion based on raw emotions, not based on fact.”

What is often missed, she said, is that employers are driving the desire to legally hire. And when they cannot, the economy suffers and worse, desperately needed services cannot function.

“There are the employers in the United States who are going berserk because they have to shut down units at hospitals because they can’t staff them,” Mdivani said.

Beyond Birthrates: Policies Stymie Immigrant Hiring

The latest high-profile warning of the U.S.’s lack of workers arrived in early January.

A research book, “Economic Policy in a More Uncertain World,” was released by The Aspen Economic Strategy Group, an arm of the Aspen Institute led by former Treasury Secretaries Hank Paulson and Tim Geithner.

The chapters could outline and build on those conversations between Kansas City-based economists.

- Chapter 5. “The Causes and Consequences of Declining U.S. Fertility”

- Chapter 6. “Why and How to Expand US Immigration”

- Chapter 7. “Will Population Aging Push Us Over a Fiscal Cliff”

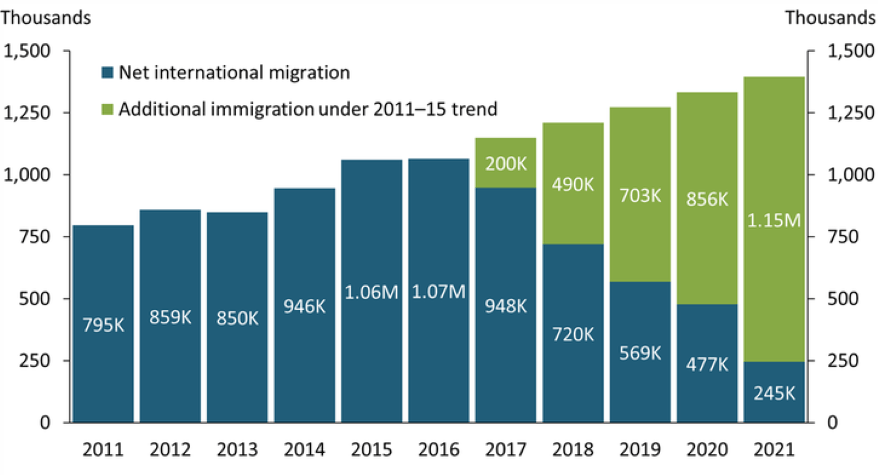

In May 2022, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City issued a paper with an ominous heading: “Immigration Shortfall May Be a Headwind for Labor Supply.”

The paper dove into how policy decisions that began restricting immigration in 2016 created a trend that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Immigration Shortfall

During the pandemic, travel was limited for some immigrants and the process of approving work visas slowed.

The result was historic lows in the movement of foreign-born workers into the economy.

According to the U.S. State Department, the number of nonimmigrant work visas issued fell from a peak of 5.5 million in 2015 to a low of 1.45 million in 2021.

One employment sector is often highlighted in such reports.

Foreign-born people are already employed in disproportionate numbers in the medical field.

But more people are needed as hospitals, clinics and elsewhere seek replacements for all those retiring baby boomers or those who left the field early during the first years of the pandemic.

In 2018, more than 2.6 million immigrants (roughly the population of Mississippi), including 314,000 refugees (more than half the population of Wyoming), were employed as health care workers, with 1.5 million of them working as doctors, registered nurses, and pharmacists, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

Dr. Paola Luna, a Vibrant Health pediatrician, is a vital resource for the clinic’s Spanish-speaking clients.

Luna is from Colombia and gained her medical training, the first time, in her native country.

But her then-boyfriend, now-husband, was sponsored by a U.S. employer to work as an architect. They married and moved to the United States in 2007.

Luna had to reassess her options to practice medicine.

She was able to get her foreign medical credentials validated, but then still needed to get accepted into a U.S. residency program, which is highly competitive.

At the time, about 2012, some were more “international friendly” than others, she said.

Eventually, she did, through the University of Kansas. And the couple settled in the metro area.

“You will see that the great majority of the international graduates will look at primary care,” Luna said. “They usually choose family medicine, internal medicine or pediatrics.”

Increasingly, doctors with insights that are innate to Luna’s identity as a Latina are being valued.

The last thing that an institution wants to risk is compromising the health of a patient due to a language miscommunication or because staff misinterprets what is a culturally based belief about medicine.

For instance, many Latino mothers believe that a chubby baby is always the healthiest, when in reality a skinnier one can be just as healthy, Luna said.

“There are so many things that I see in the practice,” she said. “We make it more like learning about their culture and also accepting it.”

A common occurrence is to explain to a patient which folk remedies are well-founded and which ones might need to be avoided, but to do so without demeaning the family’s beliefs.

Luna is fluently bilingual in English and Spanish. After more than 15 years, she is acclimated to the U.S. workplace.

In many ways, her journey from abroad to becoming a sought-after U.S. worker is one that employers everywhere are hopeful that other highly skilled immigrants will eventually follow.

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS. Cody Boston is a video producer for Kansas City PBS.