Take 5 for your health A Quick, Clickable Roundup Of Health News From Our Region For The Fourth Week of October

Published October 27th, 2015 at 7:55 AM

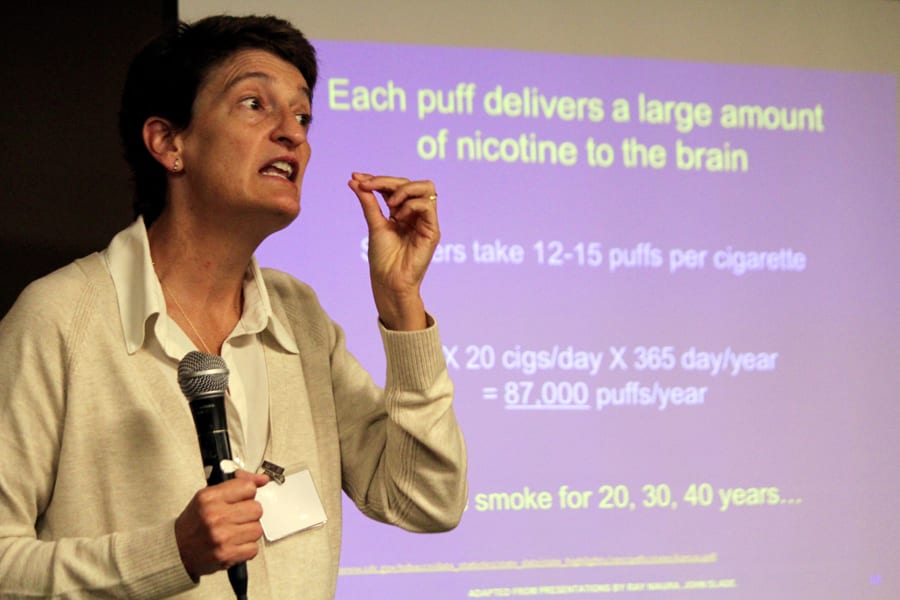

KU Tobacco Cessation Expert Sees ‘Big Disparity In Who’s Smoking And Who’s Dying’

Studies have shown that nearly half of the cigarettes consumed in the United States are smoked by people thought to have a mental illness. At the same time, people who have a mental illness die an average of 25 years earlier than those who don’t have a mental illness.

“There’s a really big disparity in who’s smoking and in who’s dying,” said Kim Richter, who runs the tobacco cessation program at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kan.

“And we as a society haven’t really done anything about this,” she said. “We really need to turn this around.”

Richter led a Saturday session, “Mental Illness & Tobacco Use: Why Do I Smoke and What Will Really Help Me?” during the National Alliance on Mental Illness-Kansas annual conference in Topeka.

Efforts to reduce smoking among people with mental illness, she said, have long been hamstrung by the perception — especially in the state’s medical community — that people can quit smoking if they really want to, and until they want to quit, cessation efforts are a waste of time.

“I think we forget how formidable tobacco is in people’s lives,” Richter said.

Richter said her average patient at the KU hospital has been smoking for 29 years.

Richter said surveys have found that most people who try to quit smoking take a “cold turkey” approach that doesn’t include counseling or cessation medication. These efforts, she said, typically have a 5 percent success rate.

For people with a mental illness, the success rate is between zero and 3 percent. “It’s very low,” Richter said.

But she said that success rate significantly improves when patients take advantage of cessation counseling and medications, most of which are now covered by private insurance, Medicaid and Veterans Affairs benefits.

— Dave Ranney is a reporter for KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

New CASA Program Will Help Foster Kids Transitioning Into Adulthood

Growing up in foster care can be challenging, but many of the biggest problems foster children face occur after they age out of the system.

Among the sobering statistics: More than one in five become homeless, nearly three out of four girls become pregnant by age 21 and only half are gainfully employed at age 24, according to the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, a national foundation that assists young people leaving foster care.

Two local chapters of the national nonprofit Court Appointed Special Advocates, or CASA, on Wednesday announced the creation of a program to help foster children prepare for the time when they’re too old to qualify for foster care.

Jackson County CASA Executive Director Martha Gershun described it as similar to the mentoring and life preparation children receive from parents in traditional families.

The CASA Transition Program for Older Foster Young will employ a case manager to help them find medical, educational and therapeutic services they can use as adults.

Children will begin working with the case managers starting at age 15. In Kansas, foster care services end when children turn 18. In Missouri, they end between the ages of 18 and 21.

Organizers say the program will serve about 75 foster children in Jackson County, Missouri, and Johnson and Wyandotte counties in Kansas in the first year. About 1,640 children are currently under court protection in the three counties.

— Alex Smith is a reporter for KCUR, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

Valley Hope President and CEO Pat George shares a laugh with Kansas House Speaker Ray Merrick, left, and U.S. Rep. Kevin Yoder, right, before cutting the ribbon on a new outpatient abuse treatment facility in Overland Park, Kansas. (Photo: Andy Marso | Heartland Health Monitor)

‘Step-Down’ Substance Abuse Services Highlighted In Johnson County

Pat George opened a renovated substance abuse facility Monday in Overland Park, Kansas, as the president and CEO of Valley Hope addiction services and a recovering alcoholic himself.

George quit drinking decades ago and has since served in the Kansas Legislature and as Gov. Sam Brownback’s commerce secretary. But he said his addiction to alcohol almost killed him before he checked into a Valley Hope treatment center in 1991.

“Nearly 24 years later, I’m clean and sober here today, and I’m not bashful to say Valley Hope saved my life,” George said.

George was flanked by U.S. Rep. Kevin Yoder when he cut the ribbon on an outpatient treatment center. State officials say the “step down” services the center will help keep recovering addicts on course after they leave inpatient institutions.

Valley Hope, which has 16 centers in seven states, previously had a small facility in Mission that operated out of a former residential home. About $1 million in renovations went into the new building in Overland Park and an adjoining tech center that Valley Hope uses to operate an online therapy program that’s also part of its outpatient offerings.

About 12,940 Kansans entered treatment in fiscal year 2015.

— Andy Marso is a reporter for KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

Kansas Budget Woes Deepen Anxiety About Malpractice Fund Sweep

Kansas budget shortfalls are increasing concerns that the Legislature may divert money from a $271 million fund used to cushion the cost of medical malpractice claims.

Such a move could increase health care costs if providers were forced to pay more into the fund to replenish it.

The Health Care Stabilization Fund oversight committee decided Wednesday to include language in its annual report urging lawmakers not to sweep money from the fund.

“This is funded by the providers of the state and the hospitals,” said Dennis George, a former hospital administrator who is on the oversight committee. “It’s not a quote ‘tax,’ it’s for a specific purpose. And to protect that as an oversight committee, I want to recommend we use strong language to keep it in trust so it’s not diverted for other purposes by the state.”

The committee decided to adopt that language after hearing from Jerry Slaughter, executive director of the Kansas Medical Society, an advocacy group for doctors.

Slaughter said that given tight state budgets and recent sweeps of other funds, the Legislature might need a reminder not to touch the stabilization fund.

“We understand it’s an attractive target because it has $270 million in it and the state’s in a difficult budget position right now,” Slaughter said. “But these funds are held in trust.”

Fund serves as backstop

The stabilization fund was formed almost 40 years ago to make health care providers’ medical malpractice costs more predictable year-to-year.

It is funded through a surcharge on providers’ regular malpractice insurance. If providers’ claims exceed their regular coverage, the fund provides a backstop.

The fund had about $271 million in assets when the fiscal year ended June 30. But it also had about $223 million in liabilities.

Chip Wheelen, the fund’s executive director, said that leaves about an 18 percent margin of error in reserve.

In Kansas, money from the Health Care Stabilization Fund has been diverted only once. In 2009, then-Gov. Mark Parkinson ordered a series of allotments after the recession pushed state finances into the red.

The following year the Legislature passed a law stipulating that the executive branch could no longer unilaterally divert the funds. But Wheelen said that doesn’t necessarily mean the reserves are secure.

Large income tax cuts passed in 2012 have led to tight budgets in recent years. The 2015 session was the longest in history as legislators struggled to end a stalemate over raising taxes.

Gov. Sam Brownback and the Legislature have tapped other special funds to shore up the general fund, most notably one within the Kansas Department of Transportation that’s intended for highway projects.

— A. M.

Lawrence Memorial Hospital Calls Fraud Lawsuit ‘Baseless’

Lawrence Memorial Hospital is forcefully denying fraud allegations made in a whistleblower lawsuit filed by a former employee.

The lawsuit was originally filed under seal in May 2014 by former emergency room nurse Megen Duffy and unsealed this summer. It charged that the hospital defrauded the federal government by submitting falsified Medicare and Medicaid claims.

In its response last week, the hospital charged that Duffy’s lawsuit and her failure to disclose it violated the terms of a settlement it reached with her after she was fired.

“By bringing a purported claim against LMH for alleged violations of the False Claims Act, which was concealed by Duffy from LMH at the time she entered into the agreement, and by making the scurrilous accusations set out in her purported complaint, Duffy has breached the terms of the agreement,” the hospital alleged.

Duffy was fired in October 2013 for threatening a co-worker, according to the hospital. LMH said it agreed at the end of that month to pay her $9,000 to avoid the “nuisance” of litigation. Had it known that Duffy filed the whistleblower lawsuit under seal in May 2013, the hospital said it would not have entered into the agreement.

LMH is seeking unspecified damages from Duffy to cover the costs of defending itself against the lawsuit and for “enduring public disparagement” caused by her “baseless allegations.”

Duffy’s lawsuit, filed under a federal law that allows whistleblowers to act on behalf of the federal government, was unsealed after the U.S. Justice Department investigated the charges and decided not to intervene in the case.

Robert Collins, Duffy’s attorney, said the department’s decision didn’t necessarily reflect on the merits of the case. He said the department intervenes in fewer than 25 percent of the cases pursued on the government’s behalf because of staffing limitations and other factors.

Duffy alleged that emergency room personnel at LMH were instructed to alter the arrival times of possible heart attack patients to coincide with timestamps automatically generated when patients were connected to electrocardiogram monitors.

Showing that patients were being monitored the minute they arrived significantly improved LMH’s performance data and qualified it for higher incentive payments from the federal government, according to Duffy’s complaint.

In its response, the hospital denied altering records and said Duffy’s allegations were based on “an incorrect understanding of reporting obligations” and the mistaken assumption that the time at which electrocardiogram monitoring begins cannot be reported as a patient’s arrival time.

The hospital cited the same treatment guidelines referenced in Duffy’s complaint but argued they don’t support her allegations.

Instead, it said, “These guidelines confirm that emergency department ECG reports are one of the types of documentation that may be used to document hospital ‘arrival time.’”

Under the federal False Claims Act, whistleblowers alleging fraud are entitled to between 25 percent and 30 percent of whatever money is recovered. Duffy’s lawsuit doesn’t specify a damage figure, but Collins said that, when combined with penalties, it could reach as high as $10 million.

— Jim McLean is executive editor of KHI News Service in Topeka, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.

The Heartland Health Monitor is a reporting collaboration among KCUR, KCPT, KHI News Service and Kansas Public Radio focusing on health issues in Kansas and Missouri.