- Home | News & Issues |

- Country Club Plaza Diners Seek More Local Flavors

Country Club Plaza Diners Seek More Local Flavors Hopes Surge That New Owners Lure More Local Chef-Driven Restaurants

Published November 10th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Megan and Colby Garrelts brought Rye Plaza, a Midwestern farm-to-market restaurant concept, to the Country Club Plaza nearly six years ago. (Dominick Williams | Flatland)A description of the classic board game Monopoly: Kansas City Edition entices players to gobble up property by offering “the chance to go on a shopping spree at the historic Country Club Plaza and eat way too much of the best BBQ in the country.”

Kansas City’s most iconic piece of real estate opened in 1923. The Moorish-inspired towers, stucco, ironwork and fountains span 15 blocks and boast 30 restaurants, including Fiorella’s Jack Stack Barbecue, known for hickory-smoked lamb ribs, burnt ends, cheesy corn, pit beans and hand-breaded sweet onion rings.

“Historically, we’ve been operating in south Kansas City and watching the city evolve,” says Case Dorman, owner of the fourth-generation, family-owned business established in 1957. “We always thought of the Country Club Plaza as a beacon of where we wanted to go.”

Jack Stack added the Plaza restaurant in 2006. After weathering some lean years, Dorman says sales for the location are trending upwards and there is a renewed sense of “momentum.”

The Country Club Plaza is “still a place where visitors like to go,” Dorman says, “although for locals, it’s lost some of its vibrancy.”

Some of that optimism has been fueled by recent reports that the Plaza may soon be under new ownership.

Taubman Centers and Macerich Co., which jointly bought the Plaza for a jaw-dropping $660 million in 2016, recently defaulted on a $295 million loan. Since then, reports have circulated that the owners of Highland Park Village, a successful Dallas-area project modeled on the Plaza, are interested in buying the iconic Kansas City landmark at a steeply discounted price.

A reduced purchase price could offer the prospective new owners financial flexibility to rejuvenate the Plaza with a more local flavor.

But that job may be more difficult than passing GO to collect $200.

The Plaza’s current restaurant mix skews toward national and regional chains such as P.F. Chang’s, The Cheesecake Factory, Bucca di Beppo and Cold Stone Creamery.

David Block, president of Block & Co. Inc. Realtors, which has offices in the historic Skelly Building, sees “a significant amount of transition” on the Plaza. Steep rents have pushed local independent operators to other parts of the city.

Block takes credit for initially bringing Houston’s to the Plaza in the mid-1980s. The restaurant remained for 30 years but left in 2017, leaving the space they occupied vacant.

“People had to come here to eat at Houston’s,” he says.

Other iconic restaurants, also have left the Plaza. Bristol Bar & Grill, now Bristol Seafood Grill, headed south to Town Center Plaza when its lease was not renewed, then returned to the Missouri side of the state line with a downtown location.

“Hopefully, this (trend) can be rectified with new ownership, and they can rent properties at a rate local and regional tenants can afford,” Block says. “We need more exclusive types of restaurants that you can only frequent on the Plaza.”

By Another Name

Andrea Broomfield grew up dining at Country Club Plaza restaurants with her family, including Houlihan’s, where she could never resist ordering the fried zucchini with ranch dressing.

While a student at the University of Kansas in 1988, she saved up for a fancy dinner at Alameda Plaza Rooftop Restaurant.

“I was 21 and on a lark this guy and I drove from KU to the Alameda because in my mind these places where my parents went to dine sounded so elegant and sophisticated,” she says.

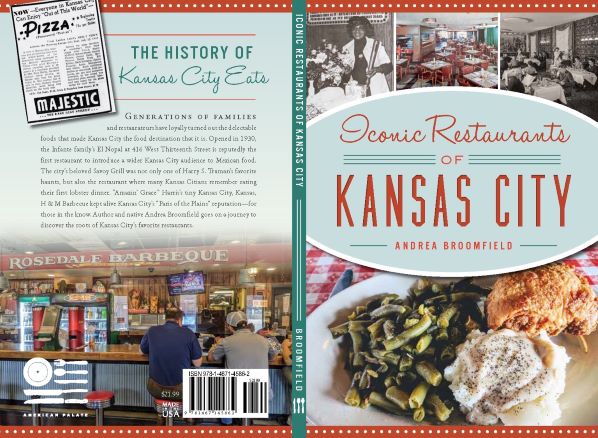

But as she researched her books “Kansas City: A Food Biography” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016) and “Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City” (American Palate, 2022), her memories began to tarnish as she learned about the history of racial segregation enforced by the Plaza’s founder.

“There’s no way for me to think about the Plaza without thinking of J.C. Nichols and the fact that the Plaza was not created for Kansas City,” she says. “If you were of color out walking around on the Plaza in the 1970s-1980s, you would have been harassed. It’s just always been an area that is considered white, and entirely by design.”

A fountain bearing the J.C. Nichols name, which became a gathering place for Black Lives Matter protesters after George Floyd’s death, has been stripped of its title, and the parkway that bore his name has reverted to its original name Mill Creek Parkway.

“We should have a series of forums, kind of like in South Africa for reconciliation, to talk about nasty history and where we go today, so that this space is something that we can acknowledge the past and look forward to a better future,” Broomfield says.

Watch on Kansas City PBS

Pride of Place

J.C. Nichols devoted nearly half of the Plaza’s area to free parking spaces, and although modern Kansas Citians still prize plentiful parking, driving past a suburban Cheesecake Factory only to dine at the one with a Plaza address turns out to be a waste of time and money.

Concerns about security, a surge in online shopping since the COVID-19 pandemic and a decline in business lunches have made restaurant habits harder than ever to predict.

But Megan and Colby Garrelts didn’t shy away when the chance came to roll the dice on some Plaza real estate.

“Everything has cycles and a kind of ebb and flow, but I think we’re going to see an uptick again,” Megan says.

For nearly six years, the award-winning husband-and-wife chef team have operated Rye Plaza, a Midwestern farm-to-table concept offering such signature dishes as fried chicken, shrimp and grits and lemon meringue pie.

“Colby grew up here. As a restaurateur, a dream of his was always to have a restaurant on the Plaza,” Megan says. “It was known as the beachfront of Kansas City at the time, and still kind of is, so it was always a goal to have a restaurant there. But I think it felt unattainable when we just had Bluestem because we were such small operators.”

Bluestem, their intimate fine-dining concept located in Westport, closed during the pandemic.

With the success of Rye Leawood, the couple had enough clout to negotiate the terms of their lease. Six years ago, the Garreltses moved into one of the Plaza’s oldest buildings at 4646 Mill Creek Parkway with a view of the most photographed fountain.

After peeling back “layers of corporate construction,” they added a bar to the private dining room. While their Leawood location tends to book more corporate events, the Plaza location tends to host “grander occasions,” such as weddings and special celebrations, for a mix of locals and out-of-towners.

Regional tourism has always played a vital role in the success of the Plaza, but when it comes to what’s for dinner, tourists tend to stick with the tried-and-true chains.

“That’s why you need the hotels and the community to say, ‘Don’t go to what’s familiar, go to what’s local,’” Megan says.

The distinctive architecture and walkable streets, and special events like the Plaza Lights and the Plaza Art Fair, continue to be a draw.

“The Plaza is a KC tradition,” Megan says. “Whether you are going there or not, you say ‘The Plaza’ and everybody knows what you are talking about, and that is the one thing I think will never change, especially for people who have grown up here.”

A Brief History of Plaza Restaurants

Built for nearby neighborhoods surrounding the Country Club Plaza, the iconic shopping district layout initially included amenities like a grocery, gas station, drug store, bowling alley and eateries.

An early restaurant standout, Putsch’s cafeteria started with a location downtown and then added another on the Country Club Plaza. As other spaces around the cafeteria became available, owners Virginia and Jud Putsch added a coffee house and a sidewalk café.

In 1947, they added Putsch’s 210, a fine-dining concept featuring a dress code, white tablecloths, fine china, tableside flambéed dishes, such as Steak Diane or bananas Foster, and strolling violinists.

The success of Putsch’s 210 included the notable contributions of African American bartender Willie Grandison and Mexican American Chef de Cuisine Herman Sanchez. In 1971, at the height of their success, the Putsch’s sold to Montgomery Ward.

“The name Putsch’s resonate(s) with Kansas Citians who associate the Plaza’s golden age with a time when businesses were local, the food was made from scratch and all manner of gustatory tastes were accounted for,” local author Andrea Broomfield writes in “Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City.”

In the 1960s, the restaurant group Gilbert Robinson specialized in what would eventually be known as the concept restaurant. Their roster included such iconic restaurants as Plaza III Steakhouse, Annie’s Santa Fe, The Bristol, Fred P. Ott’s and Houlihan’s.

Gilbert Robinson restaurants marked a transition to more casual dining, offering the freedom to eat what you wanted, when you wanted it and to use the spaces as a gathering spot for every occasion, not just special occasions.

“Suddenly you were able to afford a night out without getting really dressed up, and you’re not forced to deal with strolling violins and fine china or having the requisite number of courses,” Broomfield says.

Through the 1990s, many of the Gilbert Robinson restaurants were bought up by Nabil Haddad, including the short-lived Jules, a replacement for The Bristol, which had taken the restaurant’s spectacular glass dome when it moved to Johnson County, leaving the “live” mermaid in the new seafood restaurant’s aquarium to flounder.

Jill Wendholt Silva is Kansas City’s James Beard award-winning food editor and writer.

More on Flatland

Nichols’ Folly: A Century of the Country Club Plaza The Country Club Plaza, as it marks its centennial, is at a crossroads. J.C. Nichols’ iconic district is seen both as private property and public trust.

Like what you are reading?

Discover more unheard stories about Kansas City, every Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!

Check your inbox, you should see something from us.

Ready to read next

This Flatland article, as well as “Nichols’ Folly” on PBS do not accurately identify the problems now present in the Country Club Plaza. Although racial discrimination was built into Nichol’s original Plaza, this was not unique, but rather it was a widespread cultural divide – all across the US. It was a dark historical record that has been addressed, but not fully resolved. But this is not what ails today’s Plaza. Rather it suffers from constant upward valuation of real estate, especially in a city that has no appetite for density – leading to sprawl and disinterest in historically notable developments such as this once international gem/the Plaza.

The shops were once very diverse in the many services provided for the surrounding communities. There were high-end shops for fine clothing and home furnishings to be sure. But of even greater import were those shops, markets and stores that served all income strata surrounding “The Bowl.” There were hardware, grocery, shoe stores, department stores (Montgomery Ward/Sears), dental and medical offices, and only a few discreet restaurants. The Plaza’s history is somewhat misrepresented in today’s struggle to find the culprit for its status in 2023. This once active and vital commercial center no longer serves its neighborhoods, but relies heavily on “tourism” – even if these visitors are from nearby suburban areas – i.e. the sprawl. If The Plaza actually is to survive and find another century ahead, the thinkers/planners/owners and users will need to decide “just who is this Plaza trying to serve.”