- Home | News & Issues |

- Nichols’ Folly: A Century of the Country Club Plaza

Nichols’ Folly: A Century of the Country Club Plaza Iconic Shopping District Seen as Both Private Property and Public Trust

Published November 9th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: The Country Club Plaza is marking its 100th anniversary in business this year amid renewed questions about its future. (Courtesy | Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library)The shareholder – or, rather, stakeholder – meeting of the Country Club Plaza happens every day.

It convenes in coffee shops, bars and restaurants. It continues in stores and on street corners. It permeates dinner parties, neighborhood meetings and – sometimes – angry public protests.

For a century now, pondering the Plaza has been a quintessentially Kansas City pursuit. It has served as a prism through which to understand our city and, by extension, ourselves.

Residents talk about the Plaza like they talk about the city’s pro sports franchises – endless unsolicited advice often accompanied by little or no personal investment.

That they have no actual equity stake in the iconic district that displaced an aging downtown and served as a springboard for suburban sprawl doesn’t prevent them from behaving like activist investors questioning board policy.

Their regard for the Plaza is that proprietary.

“How many people believe the Plaza is theirs?” asked Ken Block, managing principal of Block Real Estate Services of Kansas City, which long has developed office and residential properties across Kansas City, including the Plaza area.

“Whether they have money in it, or don’t have money in it, it’s all about their opinions.”

That’s exactly the point, said Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas.

“I think there’s this idea that the Plaza isn’t just property, that it belongs to everyone, that it belongs to this community,” Lucas said.

“I wouldn’t say necessarily legally that we own it. But I certainly think that after a century, Kansas City has some claim to ownership.”

Watch on Kansas City PBS

‘Nichols’ Folly’

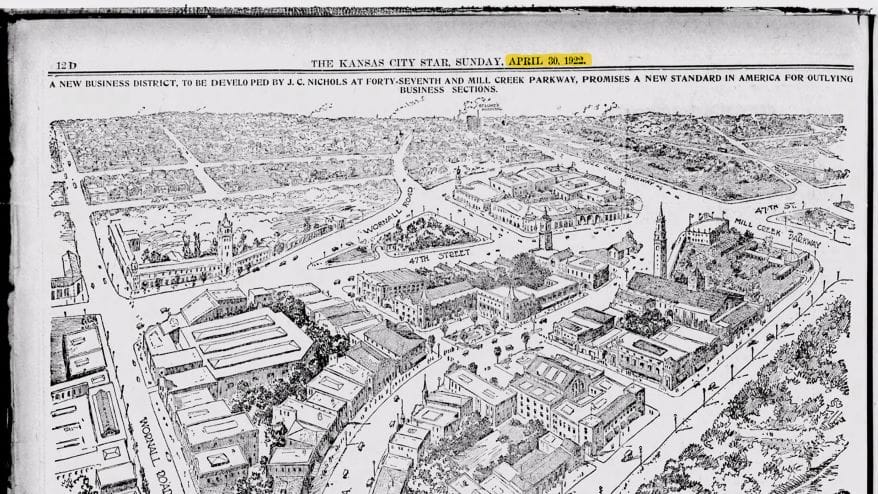

Jesse Clyde “J.C.” Nichols, then a 41-year-old real estate developer, announced his vision for the Country Club Plaza in an April 1922 interview with The Kansas City Star.

A panoramic map of the 30-acre district accompanied the article, and the first new Plaza property, the Suydam Building at 4638 Mill Creek Pkwy., opened a year later.

At some unknown moment, the phrase “Nichols’ Folly” began to circulate, an eye-rolling stage whisper that suggested quiet mirth among Nichols’ peers at his plans for a car-centric shopping center so far south of downtown Kansas City.

Nichols’s vision – at least his recognition and acceleration of the city’s evermore suburban development pattern over the following decades – has been vindicated.

Yet the district’s centennial – a moment for commemoration if not celebration – is occurring at a moment of renewed doubt and uncertainty.

To be sure, not all of the anxiety is unique to the Plaza.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing rise of online retailing have challenged brick-and-mortar shopping nationwide, the Plaza included. A 2022 survey by the Star noted more than two dozen empty Plaza storefronts.

“Retail is just hard, way harder than it used to be,” said Jesse Clyde “Jay” Nichols III, a grandson of the developer. The younger Nichols opened a bell-bottom pants store on the Plaza in 1970.

“But today, if you really want something, you just go on your computer and it arrives on your doorstep.”

But other angst is unique to the Plaza.

The 2019 closure of the Cinemark Palace on the Plaza movie theater, and the subsequent demolition of its square footage just west of Jefferson Street and Nichols Road, was supposed to suggest a new beginning.

The previous year representatives of the retailer Nordstrom had announced they would be vacating their Oak Park Mall space in Overland Park for the Plaza, filling in that newly cleared parcel with a 122,000-square-foot store.

Many believed a new anchor tenant might revitalize the Plaza.

The store was expected to be completed by 2021 – which came and went before the parties acknowledged the deal fell through the following year.

Then, in May, Taubman Centers and the Macerich Co., the two out-of-state shopping center operators that bought the Plaza for an eye-popping $660 million in 2016, defaulted on a $295 million loan.

Despite the default, some have wondered whether this could be yet another opportunity.

Recent news that the owners of the Dallas-area Highland Park Village shopping center, which includes members of the extended Hunt family, are possible buyers was seen as a chance for a Plaza reset.

It’s possible, according to sources, the transaction could be completed by the end of the year.

A Brief History of the Country Club Plaza

Complicated Legacy

This summer, to mark the Plaza’s 100th anniversary, Kansas City PBS/Flatland invited a wide range of Plaza stakeholders to discuss the district’s past, present and future.

While a Taubman spokesperson “kindly” declined to participate, 14 area residents did.

They had many opinions:

- Some mentioned security, or the perceived lack of it.

- Others critiqued the Plaza’s current mix of retail tenants, and the possible benefits of more local merchants as opposed to national retailers or restaurant chains.

- Still others wondered about the impact of Main Street streetcar extension, expected to be completed by 2025, and what effect that might have on the Plaza’s free parking. Maybe, some wondered, transit patrons would just park for free on the Plaza and then take the streetcar someplace else.

- Several suggested more high-rise housing and office development would help the Plaza by increasing the population of nearby patrons.

- Some mentioned the possibility of some Plaza streets being closed or modified, setting aside space for a more pedestrian-friendly experience.

- A few suggested more activities along Brush Creek.

- Many spoke of how the Plaza-adjacent Mill Creek Park came to be recognized as Kansas City’s agreed-upon town square, a community space set aside for everything from prom pics to protests.

- And, most prominently, all grappled with the complicated legacy of J.C. Nichols and how the developer’s use of restrictive racial covenants in his residential subdivisions contributed to Kansas City’s stark racial divide.

Demonstrations following the May 2020 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis occurred in Mill Creek Park and along the Plaza’s eastern edges.

Kansas City police used tear gas to disperse protestors. Some property damage occurred inside the district, and police shut off street access.

That June the Kansas City Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners unanimously chose to remove Nichols’ name from the Mill Creek Park fountain installed and dedicated by the Nichols family in 1960.

The street along the park’s western boundary, known since 1952 as J.C. Nichols Parkway, reverted to its original name of Mill Creek Parkway.

The parks board chose to act following a statement from Nichols family members supporting the name’s removal.

“You know, it was really the only thing to do,” Jay Nichols said.

Kay Callison, a granddaughter of J.C. Nichols and president of the Miller Nichols Charitable Foundation, pledged $100,000 to maintain the fountain.

Personal Connections

When asked to name their favorite things about the Plaza, few hesitated.

Notably, they rarely mentioned the familiar seasonal traditions such as the annual November lighting of the Plaza’s holiday lights (since 1930), the arrival of 200-pound plaster of paris rabbits every spring (since 1931), or the art fair (since 1932).

What they chose to describe were deeply personal perspectives or experiences they associated with the Plaza.

“For me, the Plaza always has been the figurative front porch of Kansas City,” said Chris Goode, founder and CEO of Ruby Jeans’s Kitchen & Juicery.

In 2020 Goode, then serving as a parks board commissioner, submitted a memo advocating the removal of Nichols’ name from the fountain and parkway.

For several years he was a Plaza area resident, occupying a nearby apartment.

“One of the things I would enjoy doing was exercising on that set of stairs between McCormick & Schmick’s and H&M,” Goode said.

“I would run those stairs – up and down, up and down. It’s a great workout,” Goode said.

“But what I would enjoy most was the people I got to meet, the people who were like, ‘Who’s this crazy guy?’ I enjoyed the conversations that would come from it.”

Elizabeth Rosin, principal and CEO of Rosin Preservation, a Kansas City-based historic preservation consulting firm, mentioned the Plaza’s architecture and the juxtaposition of its dramatic Mediterranean accents almost whimsically placed next to a western Missouri creek bed.

“There’s a richness, a permanence to it which I believe was intentional, drawing from those buildings in Spain that had a past and a legacy, and then plopping them here in Kansas City,” she said.

“The brick, the terra cotta, is beautiful.”

Others described the stress that often dissipates when they admire the Plaza’s towers framed by a changing sky.

“The light is extraordinary,” said Kate Marshall, president of the Plaza District Council, a nonprofit organization devoted to ensuring the Plaza area’s future viability.

Her residence, which includes a view from near Brush Creek’s south bank, often reminds Marshall of her years spent living in Europe.

She moved from the south of France to the Plaza in 1985.

“It reminded me of these very walkable, small, manageable and human-scaled spaces and places that I had just recently lived among,” Marshall said.

But the perspective from Marshall’s windows in recent years has been less comforting. The sidewalks somehow seemed less than bustling.

“I was beginning to hear from my neighbors,” Marshall said. “They were saying ‘Oh my God, the Plaza is dying, the Plaza is falling apart.’”

If some of that represented hyperbole, Marshall herself had noticed wear and tear. After becoming president of the South Plaza Neighborhood Association, she helped secure grant money to refurbish the Sisters Cities International Bridge, which crosses Brush Creek at Central Street.

She began to consider the Plaza from a new, problem-solving perspective.

And, as for problems, plenty of those seem to remain on the Plaza.

When asked to name their least favorite things about the Plaza, there also was little hesitation.

“One of my least favorite things about the Plaza is that I still think there’s a history to be reckoned with,” said Lucas. “The Plaza was not a place where my grandmother went, the Plaza was not a place where even my mother went as a child.”

Rosin described the “blandness” of the Plaza, referring to its retailers and restaurants.

“It’s felt like anywhere else, any other upscale shopping center in the country,” Rosin said. “I think it’s lost some of what was special about it.”

If the reasons behind that are complex, one issue is not complicated, according to Jay Nichols.

Since 1998, when Nichols Co. merged with Highwood Properties Inc., a North Carolina operator of office properties, the Plaza has not benefitted from local ownership, he said.

Miller Nichols, following the 1950 death of J.C. Nichols, his father, led the company until stepping down as chairman in 1988 and – in 1995 – stepping down again as a director on the Nichols board.

He died, at age 89, in 2000.

“I just think that since Miller passed away, there’s nobody who’s been in management of the Plaza who loves it,” said Nichols.

“And it would be really nice if they put somebody in charge who loved it. Because it needs a little love.”

‘Raw Land’

In December 1920, an observant member of the Star’s staff noticed something unusual near the north bank of Brush Creek.

Earlier in the year workers had demolished the Chandler Landscape & Floral Co. building.

The firm’s new home, completed by Thanksgiving, included an unexpected touch of panache – a visually pleasing smokestack.

“Instead of a disfigurement, a deft architectural treatment has produced a smoke tower that harmonizes with immediate surroundings,” the Star noted in a two-paragraph item buried at the bottom of the Sunday financial page.

“The new building is a Spanish type, and has a color scheme much-admired in the Pan-American building at Washington D.C.”

There was no mention of J.C. Nichols, who had been advertising properties in what he called the “Country Club District” since at least 1909. Nor was there any mention of the “Country Club Plaza,” which wouldn’t be announced until 16 months later.

Nichols’ idea for a shopping district rendered with a uniform architectural theme may first have arrived by way of personal epiphany, received while bicycling through the English countryside during a 1900 trip to Europe with a college friend, Wilkie Clock.

It was then, Nichols later wrote, “that the spark was struck that ultimately brought the Country Club District into being,” according to “Hare & Hare, Landscape Architects and City Planners,” published in 2019 by Carol Grove and Cydney Millstein.

Nichols’ Atlantic passage to England had not been a privileged one.

“He didn’t have any money,” Jay Nichols said of his grandfather.

“But his dad ran a cooperative grocery, and Jesse found out that he could get to Europe if he went on a cattle boat.”

Young J.C. watched the cattle and cleaned the stalls to earn his passage.

Upon arrival, Nichols and Clock biked to London and later traveled to Belgium, Holland, Germany and Switzerland.

“He appears to have wandered about Europe for a couple of months, doing odd jobs,” said William Worley, the Kansas City historian who in 1990 published “J.C. Nichols and the Shaping of Kansas City: Innovation in Planned Residential Communities.”

Nichols, Worley said, “would always credit what he had seen there as inspiring certain aspects of what he did.”

In England, Nichols had appreciated the passing landscape from a cyclist’s perspective.

“Biking through England, Nichols noted the charm, orderliness, and what he described as the ‘stability’ of its villages,” Grove and Millstein wrote in 2019.

If that’s true, several other things had to occur in the following 20 years before Nichols announced the Plaza, which he would describe as the “gateway” to his residential developments to the south of Brush Creek.

In 1902, after graduating from the University of Kansas, Nichols received a scholarship to Harvard University.

He attended lectures given by Oliver Mitchell Wentworth Sprague, an economist who believed the country’s industrialists would soon increase their investments in the country’s West and Midwest.

Nichols submitted a thesis on “the increase in value of raw land through development,” wrote Robert Pearson and Brad Pearson in “The J.C. Nichols Chronicle: The Authorized Story of the Man, His Company, and His Legacy, 1880-1994,” published in 1994.

In 1904, after returning to Kansas City, he began building homes in Kansas City, Kansas, financed in part by college fraternity friends.

Nichols soon thereafter moved his operations to the Missouri side, preparing lots to the southwest of the Rockhill district then being developed by William Rockhill Nelson, the Star’s publisher.

In 1907, Nichols began building his first retail strip, the Colonial Shops, at the northeast corner of 51st Street and Brookside Boulevard.

Nearby residents patronized a grocery and pharmacy there. Worley, in his biography, wrote that Nichols realized that retail revenues could “challenge the income he had made in the past from homebuilding and even from land sales.”

In 1908, Nichols began advertising his Missouri residential developments as being part of the “Country Club District,” a reference to the Kansas City Country Club, which began operating on acreage near 55th Street and Wornall Road in 1896, in what is now Kansas City’s Loose Park.

In 1912, Nichols met E. H. Bouton, a Kansas City native who in the 1890s had begun developing a residential district on the north side of Baltimore named Roland Park. The development included a small shopping district featuring a uniform architectural theme, in a style often called English Tudor.

Also in 1912, Nichols directed an associate to begin acquiring parcels near Brush Creek.

The previous year a separate developer, George F. Law, had filed plans for a subdivision called the “Country Club Plaza.”

Law had begun subdividing the acreage into 25-foot lots. But sales had been slow, at least among local buyers.

“He couldn’t sell much of it in Kansas City because people here were not dumb enough to buy in a floodplain or swamp,” Worley said.

But that had not stopped outside speculators.

Nichols directed an associate to travel the country, find those buyers and acquire their lots.

In 1915, Nichols began planning the Brookside shopping district near 63rd Street and Brookside Boulevard. Eight of the first stores’ exteriors would feature a Tudor style.

In 1920, two Missouri courts ordered the Lyle Brick Co. to cease operations. Nichols’ lawyers had argued that the company’s coal-fired kilns, which stood near Brush Creek and routinely belched black smoke, were no longer an appropriate land use for the residential neighborhoods surrounding it.

Nichols later would buy the property.

In 1922, the first section in the Crestwood shopping strip at 55th and Oak streets opened. Its stores – three groceries, two pharmacies, two dry cleaner’s shops, one bakery and one shoe repair shop – would serve the basic needs of nearby residents.

That April, Nichols grandly announced the Country Club Plaza in the Star.

One year later the Suydam Building opened at the northwest corner of West 47th Street and Mill Creek Parkway.

Other buildings quickly appeared, several of them assembled in a cluster around the corner along West 47th Street. Any patron who brought his or her “list of daily household necessities” could find them at two groceries, a pharmacy and a dry cleaner’s shop available there, according to a Star advertisement placed in December 1923.

But it wasn’t what customers could buy at these stores that was newsworthy.

It was what they saw from the sidewalk.

‘A Pleasing General Order’

Nichols had assembled his Plaza parcels on the down-low, investing more than $1 million.

“Nichols did the Walt Disney thing before Walt Disney,” Worley noted, referring to the entertainment magnate from Kansas City whose associates just as quietly had bought up Florida real estate to plan Walt Disney World, which opened in 1971.

But it wouldn’t be just the scale of Nichols’ plans that startled his peers.

It would be the Plaza’s dramatic architectural theme that would remind later generations of a theme park.

In the April 1922 Star article announcing the Plaza, Nichols noted that the buildings would “follow a general Spanish type of architecture.”

Nichols added how many American downtown business districts had been “developed haphazardly…with no effort made to create a pleasing general order in the laying out of the buildings and their heights.”

The Plaza, in contrast, would feature “uniform height and cornice lines to give the orderly effect so generally praised in Paris and certain other European cities.”

“We desire harmony in the design and color of our buildings,” Nichols said.

A separate article published weeks later, detailing plans for the Suydam Building, was specific as to just what “Spanish type” architecture would look like in Kansas City.

“The arches in the end pylons will have handmade mosaic tile designs set in the buff-colored stucco,” the article read.

“The broad horizontal band at the second floor level will be ornamented in greens, blues and yellows in glazed terra cotta and the overhand of the roof also will be gay with brilliant colors.”

Several associates, Nichols said, had been researching and planning the Plaza for three years.

They included George Kessler, who by 1892 had been consulting landscape architect on Kansas City’s parks and boulevard system. In 1906 Nichols engaged Kessler to work on his Sunset Hill residential district.

In 1913 Nichols contacted S. Herbert Hare who, with his father, Sidney, had founded the Kansas City landscape engineering firm three years before. Sidney trained under Kessler, and son Herbert helped plan Baltimore’s Roland Park district.

Kessler and Hare would collaborate on the Plaza’s layout and landscaping.

But there was another collaborator, whose name had been mentioned briefly in the Star’s 1920 smokestack scoop.

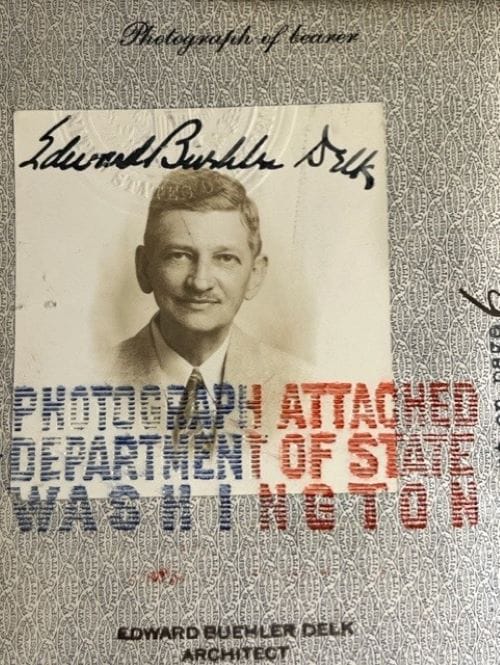

That, the Star noted, “was designed by E. B Delk.”

Edward Buehler Delk had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1907 and then left to tour Italy and Greece, studying architecture. Following World War I, he attended urban planning lectures at the University of London.

Nichols brought Delk to Kansas City in 1920 to design grand homes for buyers of his Country Club District’s larger lots.

Delk also traveled to Spain, as well as Mexico and South America.

Throughout the early 1920s, Delk designed the Suydam Building, the Tower Building, around the corner on West 47th Street, and the Triangle Building, just to the west, which featured a Piggly Wiggly grocery store.

While the design of the Plaza Theater, just across West 47th Street, is usually attributed to Edward Tanner, an architect who would have a long association with Nichols, a study of the theater can be found in a Delk archive held by the State Historical Society of Missouri-Kansas City Research Center. The theater opened in 1928.

Finally, there would be another building designed by Delk, located just behind the Suydam Building, with its own Mediterranean touches.

It was a parking garage.

Accommodating the Automobile

In 1907, Nichols built his Colonial Shops 250 feet away from a stop on the Country Club trolley line.

But that same year, some 20,000 Kansas City area car enthusiasts had attended the city’s first automobile show, held over several days at Convention Hall downtown. The following year Henry Ford introduced his Model T.

Four years later the Ford Motor Co. opened its first plant outside Michigan in the Sheffield district of eastern Kansas City.

With the advance of the assembly line, car prices dropped. In 1923 – when the Plaza’s first buildings opened – a new Ford cost only $269, approximately $4,841 in today’s money.

From 1914 through 1924, the number of privately owned cars in the Kansas City area spiked from around 8,600 to more than 89,000.

“By the early 1920s automobiles were much more perceived as viable, especially for the clientele he was aiming at, which was upper-middle class and up,” said Worley.

“He is projecting the Plaza as an automobile destination…always emphasizing free parking and more of it.”

In its early years Plaza patrons could top off their tanks at several filling stations, routinely designed with Mediterranean arches and tile roofs. During the 1930s, gas stations would provide Great Depression-proof revenues for the Nichols Co.

By the late 1930s, Nichols could not understand why downtown property owners refused to invest in free parking.

“In 1938 he went to a downtown meeting, and he told them they needed to put in free parking to keep the merchants,” Jay Nichols said.

“And they just laughed him out of the room. They said ‘J.C., we don’t need parking. We have the streetcar.’

“Well, how did that turn out?”

By the following year, 1939, what once had been 80% of people using mass transit to enter downtown had dwindled to 50%, according to “A Splendid Ride: The Streetcars of Kansas City, 1970-1957,” published in 2002 by Monroe Dodd.

Kansas City streetcars stopped running in 1957.

Nichols, however visionary he had been about the rise of the personal automobile, was not the best driver.

“My grandfather was such a great salesman,” said Nichols.

The problem was that when driving prospective tenants or buyers by properties, his grandfather didn’t always keep his eyes on the road.

So, at some point, Nichols hired a chauffeur.

The chauffeur would play a key role in an episode that helped his grandfather survive the Great Depression.

In the early 1930s, Nichols Co. received a call from Commerce Trust Co.

The bank long had been a crucial Nichols supporter. Commerce had been a source of loans that helped Nichols build high-quality residential streets, important to all new car buyers.

W. T. Kemper, the bank’s chairman, had appointed Nichols to the bank’s board of directors when Nichols was only 28, some 10 years younger than any other director.

But during the Depression, Nichols Co. had been unable to keep up with payments on its various land purchases, Worley wrote.

So one day the phone rang in the Nichols Co. offices.

“It was one of those ominous calls during the Depression,” Jay Nichols said. “You know, ‘Come on down, we’ve got to talk.’ “

At the time J.C. Nichols was traveling in South America, taking a doctor-ordered vacation to relieve his stress. After being informed of the Commerce phone call, Nichol hustled back to Kansas City.

Nichols went to Kemper’s office.

But he brought props, one of which was a heavy ring of keys, large enough to suggest the keys could unlock a lot of doors, like those on Plaza, perhaps.

“He goes into Kemper’s office and throws the ring of keys, saying ‘If you want the Plaza, you’ve got the Plaza,'” Worley said.

“And, of course, that scared Kemper, because Kemper didn’t want the Plaza, he wanted the money.

“So he starts backpedaling immediately.”

In the version of events detailed in “The J.C. Nichols Chronicle,” Kemper came in not only with the ring of keys, but an armful of company ledgers and dropped them on the banker’s desk, as well, achieving the desired reaction from Kemper.

The version as told by Jay Nichols, however, includes a dramatic reveal seen from a high distance.

His grandfather, Nichols said, had arranged to borrow a neighbor’s convertible. After pulling back the convertible top, Nichols filled its open seats with the ledgers.

Nichols then directed his chauffeur to drive downtown and park the convertible at a particular spot visible from Kemper’s Commerce Trust window.

And then, upon entering Kemper’s office, Nichols had called the banker over to that window.

The effect was sufficiently sobering, Jay Nichols said, that Kemper chose not to call any loans.

In whatever variation of the story, however, there had been nothing comic about the Nichols company’s financial issues.

“We were faced with real bankruptcy,” Miller Nichols said in “The J.C. Nichols Chronicle.”

The company, Miller Nichols added, couldn’t pay its bills “but we stayed in business because Dad convinced the bankers that they would be better off working with him by reducing the interest rate on outstanding loans.”

‘Sour Grapes’

When J.C. Nichols announced his Plaza plans in 1922, he was already secure among the ranks of Kansas City’s elite.

Following the conclusion of World War I in 1918, Kansas City leaders resolved to install a grand memorial honoring the community’s war dead.

Lumber titan R.A. Long was chosen to lead the effort, with Nichols named vice president. He also served as chair of the committee that selected the memorial’s location on the hill overlooking Union Station.

And yet – as Nichols went about building the Plaza – skepticism apparently began to circulate.

Much of it had to do with the entirely reasonable doubt about the wisdom of sinking so much time and money into retail stores near the southern edge of the city.

Beyond that, there apparently was a hog farm.

“There was a hog farm,” Jay Nichols said, “and it was swampy.”

In the early 1920s, many Americans smirked at stories involving “Florida swampland” that swindlers had been unloading on gullible buyers.

Nichols apparently seemed to be somebody who didn’t have to go all the way to Florida to sink money into swampy real estate.

All of it, Worley said, contributed to “a sense that what Nichols was doing was too speculative and experimental and almost certainly wouldn’t work in the long run. And certainly not on the scale he projected.”

And so, over time, the phrase “Nichols’ Folly” circulated – even while the Plaza had grown during the prosperous 1920s, survived the 1930s and – by 1947 – had landed a Sears department store.

“We got the first Sears store in a suburban shopping area in the United States,” said Jay Nichols.

“That was a terrific victory because it really meant that we had arrived.”

Further, store executives agreed the building’s exterior would mimic the district’s Spanish motifs with antique iron grills and other ornaments acquired personally by Nichols during a trip to Spain 10 years before.

Time magazine noted how the new store “looked like a citadel in Spain.”

By now St. Louis newspaper editors decided that Kansas City’s Plaza could not be ignored.

Visitors to the district, a St. Louis Post-Dispatch correspondent wrote that December, are “astonished to see a Sears Roebuck store which looks nothing like a Sears Roebuck store.”

In 1922, she added, “when (Nichols) announced his plans for a plaza which would ultimately cost five million dollars, Kansas City had a hearty laugh. People began to refer to the area south of the city as ‘Nichols’ Folly.’ “

She added further how they “are astonished when they see 300-year-old statues from France adorning a parking lot.”

But what Nichols had achieved, the correspondent continued, represented “the transformation of a hog lot into a model for city planners.”

Some of the sarcasm directed at Nichols may have been generated by authentic angst, according to Worley.

“I think it was an instance of wish fulfillment,” he said.

“That was particularly true with in regard to downtown merchants and even more so downtown property owners who wanted to maintain the high property values of the various stores downtown.”

But, Worley added, “as time goes on, you’re beginning to have downtown coming to the Plaza.”

In 1948, Helzberg, which had opened in 1915 in Kansas City, Kansas, opened a Plaza store.

In 1950, Emery, Bird, Thayer, which operated a huge merchandise house downtown on 11th Street, opened a Plaza location.

In 1954, Harzfeld’s, located at Main Street and Petticoat Lane since 1913, opened a Plaza store.

Smaller retailers joined the large retailers.

That included Fred Diebel, who had returned from World War II to become a partner in one of the many cigar stores that operated in downtown Kansas City.

The competition could be cut-throat, according to Fred’s son Curt, who today operates Diebel’s Sportsmens Gallery on the Plaza. Longtime customers sometimes would cross the street to a competitor to save a few cents on a cigar.

“There were a lot of cigar stores in downtown Kansas City,” Diebel said. “He wanted to break away from that.”

His father opened his first Plaza store in 1954.

By then, “Nichols’ Folly” had been revealed as a hollow playground taunt.

“It was sour grapes,” Jay Nichols said.

The Racial Divide

Growing up, Alvin Brooks and his friends knew to stay away from the Plaza.

“Don’t drive through the Plaza,” Brooks said, describing the street wisdom he and his peers learned, “because if you did you were more than likely going to get stopped, either by the police or Plaza security.

“I never did that. I pretty much listened to my folks. But others did and in most cases, they got stopped and harassed.

“So the word got around – you just didn’t go there.”

The Plaza is unique in Kansas City’s history in how it has served as a venue for litigating issues that may have only tangential connections to shopping centers and retail trends.

Examples include the issue of suburban sprawl and its role in directing Johnson County runoff into natural watersheds – contributing to the 1977 Plaza Flood. It has also been a flashpoint for planning issues involving high-rise residential or office towers and how such buildings might affect traffic congestion or property values, or even the quality of life.

Examples of the latter include the Sailors proposal of 1984, and the Polsinelli Shughart office tower proposal in 2010.

But the legacy of Kansas City’s racial divide, which many today believe J.C. Nichols profoundly contributed to through his use of restrictive covenants in his residential subdivisions, has manifested itself on the Plaza over many years.

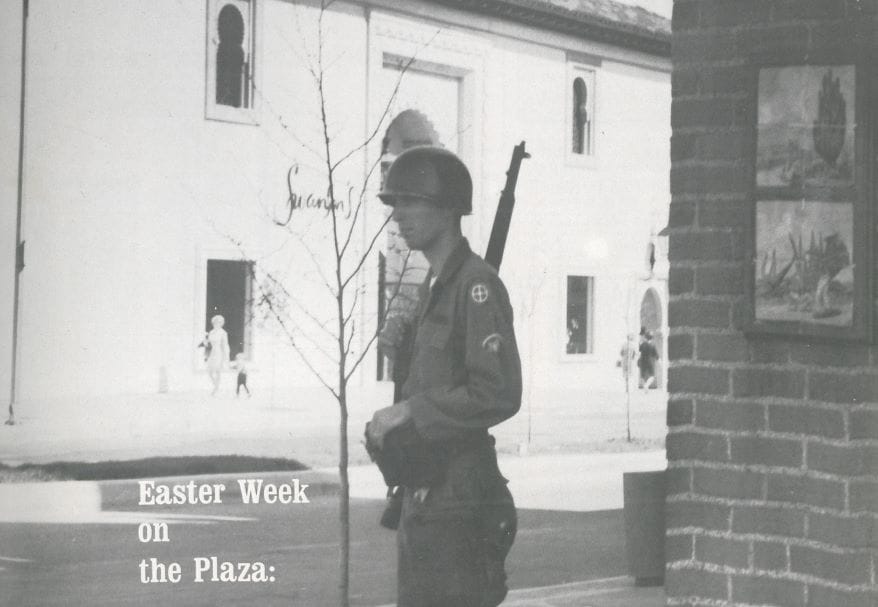

Examples include the significant deployment of Missouri National Guard troops to the Plaza during the civil unrest that followed the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., as well as the local government response to the issue of disruptive teenagers, many of them Black, on the Plaza in 2011.

During the 1920s and 1930s the Plaza had been segregated, like the rest of Kansas City.

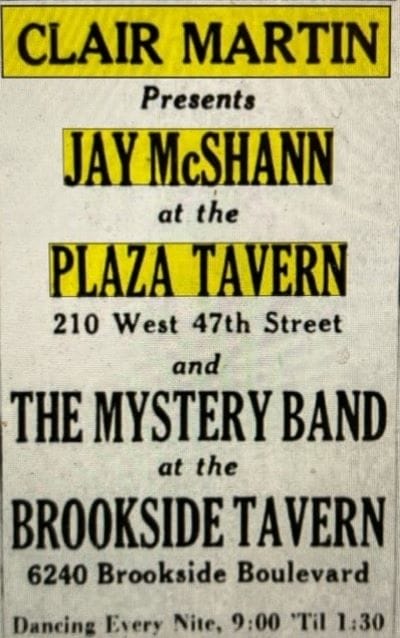

An exception in the later 1930s was driven by brilliant musicians.

Clair Martin, operator of clubs on the Plaza and in Brookside, hired some of Kansas City’s prominent Black jazz players to appear in his Plaza Tavern in the Triangle Building on West 47th Street.

In 1939, Martin placed Star advertisements announcing Plaza Tavern appearances by Kansas City jazz pianist Jay McShann.

But the Plaza Tavern seemed an outlier, as Kansas City would not stop enforcing some segregationist practices until the 1950s.

Many downtown Kansas City theaters had integrated in 1955, with many hotels soon following.

Restaurants remained an issue.

A survey by the Kansas City Commission on Human Relations reported that while 242 city restaurants served all patrons, 352 did not.

In 1957 those included the dining rooms of five downtown department stores: Peck’s, Kline’s, Macy’s, Jones Store and Emery, Bird, Thayer.

During the 1958 holiday shopping season, a Kansas City women’s club organized a sustained boycott of all five stores.

Protestors kept picket lines outside the stores through and after Christmas. In February store officials agreed to open the dining rooms to all.

But no similar social action occurred on the Plaza, and patronizing the Plaza stores was just not comfortable during those years, said Brooks.

“When you went to many of the stores, being Black, you were followed throughout the stores by either security, or off-duty police officers, or staff,” Brooks said.

“That was my experience as an adult.”

And, as a Black officer with the Kansas City Police Department in 1954 though 1964, Brooks would not receive assignments to patrol the Plaza.

“That was off limits for Black police officers.”

During the civil unrest that followed the April 4, 1968, assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Brooks was working for the Kansas City Board of Education, where in 1965 he had been appointed the coordinator of parents and student relations and community interpretation. Brooks also led the local Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter.

Brooks and others had tried – and failed – to convince Kansas City School District officials to close schools on April 9, the day of King’s memorial service. That morning, many students walked out of class and began to march. Violence followed over several days.

Five men and a teenager, all of them Black, died.

In late April, a city inspection team reported an estimated $915,000 in damage occurred in Kansas City from April 8 through April 14. While the report documented the damage had been concentrated on the city’s East Side, damage also occurred “at various places on the Country Club Plaza,” according to the Star.

From April 9 through April 17, members of the Missouri National Guard served in Kansas City.

On the afternoon of April 9 Guard units received word that the Kansas City police believed “shopping centers will be hit tonight over (a) wide area.”

An after-action report documented resources deployed to the Country Club Plaza by the evening of April 9, including 155 Guard members.

In comparison, 111 men rode along in Kansas City police cars, 20 men reported at a forward police command post at Linwood Avenue and the Paseo, and 60 men waited in reserve at 3620 Main St. armory.

“I recall that there were attempts by some of the folks who were engaging in the civil unrest to come to the Plaza,” said Gwendolyn Grant, president and CEO of the Urban League of Greater Kansas City.

Those attempts were not successful, said Grant, adding that the bulk of the unrest occurred at several locations on Kansas City’s East Side.

One of the police commanders, Brooks added, “assured the businesspeople at the Plaza that ‘We’ve got them contained down there, they won’t get out here.’

“There was certainly the feeling that all of the attention was given to the Plaza, but very little was given to the folks who lived east of Troost.

“And that was a fact.”

Brooks later became director of Kansas City’s Human Relations Department, the city’s first Black department head, and a Kansas City Council member and mayor pro tem. In 1977, he organized the Ad Hoc Group Against Crime. And in 1991, Miller Nichols, Nichols Co. chairman, would serve as fundraising co-chairman securing the $35,000 needed to buy a former Troost Avenue bank building for the group’s permanent headquarters.

Nichols also would join marches led by Brooks and others to protest crack houses.

But in 1968, Nichols was worried about the Plaza.

“Miller was thoroughly beside himself,” said Worley. “He got the governor to literally put tanks on the east edge of the Plaza.”

On this point the Guard after-action report is ambiguous.

A chronology for April 10 noted that at 8:31 p.m. Guard personnel delivered “APCs” to Linwood Avenue and the Paseo. The abbreviation in military context often stands for “armored personnel carrier,” which sometimes will present a silhouette like a tank, without the turret.

On April 10, 1968, Miller Nichols sent a memo to employees.

“These are certainly trying times for all of us in the metropolitan area of Kansas City,” Nichols wrote in the note contained in the J.C. Nichols Co. scrapbooks collection today maintained by the State Historical Society of Missouri-Kansas City Research Center.

Nichols thanked employees of the company’s carpentry maintenance department for repairing window damage in both the Plaza and the company’s Landing Shopping Center at 63rd Street and Troost Avenue, adding “I want to express general appreciation to everyone in the company who has shown such a great interest in the peculiar problems that are facing us just at this time.”

Protest Park

The legacy of unrest on the Plaza could be discerned while he was a high school student, said Sly James, Kansas City mayor from 2011 to 2019.

“Growing up in the sixties it (the Plaza) was a center of some controversy,” said James.

“There was always a little bit of racial issue in going to the Plaza, and being Black, and hanging out with some kids from my high school, who were all white – it kind of gave me a little bit of a pass.

“But it was always a little bit of a sub rosa feel that I had on the Plaza.”

James graduated from high school in 1969.

Three years later, Emanuel Cleaver, a 26-year-old activist, brought social action to Mill Creek Park.

As head of the Kansas City chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Cleaver organized a “Resurrection City,” or tent city like the temporary community built over several weeks along Washington D.C.’s Reflecting Pool following the 1968 killing of Martin Luther King Jr.

While the parks department declined to issue a permit for tents, the demonstration went forward regardless.

Its purpose, said Cleaver, was to dramatize the disparity between those shopping on the Plaza and those living just down the street from the Plaza who couldn’t afford to shop or eat there.

“So we drew a distinction,” Cleaver said.

“We also drew the FBI, undercover agents, and we drew a great deal of criticism from the Nichols company and their lawyers.”

The Kansas City community, over time, accepted Mill Creek Park as their free speech venue of choice.

Another racial issue presented itself on the Plaza in 2011, when Kansas City officials tried to respond to the concern of Plaza merchants about the behavior of teenagers.

“There were all kinds of inappropriate behavior on the part of teenagers who lacked other recreational options,” said Gwendolyn Grant of the Urban League.

“There had been calls from the Plaza merchants to have something done, a curfew of some sort, about the kids who were on the Plaza,” added Sly James, elected Kansas City mayor in 2011.

“Unfortunately, it was a very racially tinged conversation, as the kids they were complaining about were Black.”

James was in the Plaza one night in August 2011 when gunshots went off, leaving several teenagers injured.

Members of James’ security detail pushed him to the ground.

City officials soon instituted curfews in several Kansas City entertainment districts, the Plaza among them.

They also organized supervised activities for young people on the East Side. That proved effective, James said.

“First you have to understand that the Plaza was like a beacon for kids who lived on the East Side,” he said.

“There were no movie theaters on the East Side, there was no real shopping on the East Side.”

Shopping, however, would evolve in unexpected ways over the Plaza’s 100 years.

High Life, High Rises

The Plaza had started as a place for shoppers to secure essentials.

As a Nichols Co. 1923 holiday season newspaper ad pointed out, the Plaza included a pharmacy, two groceries – Wolferman’s and a Piggly Wiggly – and a dry cleaner’s shop.

But, as the same ad pointed out, it also offered shops that offered lingerie and “tea gowns,” and an interior furnishings firm, the Suydam Decorating Co.

So the Plaza could be, as the same advertisement point out, where patrons could bring their “list of daily household necessities,” but also find the “little luxuries you have been promising yourself…”

This dynamic had been noted by the editors of “The Merchants’ Journal” trade publication. Its coverage, in turn, was reprinted in a 1925 Kansas City Star advertisement bearing the headline “$300.00 Underwear – and 7 1/2 Cent Grapefruit,” placed by the self-service Piggly Wiggly chain.

“But the fact is that many of the Mission Hills aristocrats who wear the $300 underwear and live in houses furnished by Suydam come to the Piggly Wiggly in person and buy their groceries,” it read.

The Plaza kept its common touch for decades, perhaps best exemplified by the bowling alley.

The Plaza Bowl opened on Nichols Road in 1940. J.C. Nichols, according to the Star, had rolled a strike on its opening day.

The building, designed in the Spanish style by architect Edward Tanner, was a Plaza landmark for decades.

“I had some reprobate friends,” said Jay Nichols, “who would steal the bowling balls out of the bowling alley and then go up to the top of Wornall Hill, south of the Plaza, and let them roll down the hill.”

The bowling alley was still there in the mid-1970s when some wondered whether they could discern a subtle change.

The Sears store, so celebrated in 1947, had closed in 1975. The Nichols Co. bought the building at 500 Nichols Road and remodeled it, rebranding the location as Seville Square, which was a collection of restaurants and small specialty shops.

Seville Square opened in 1977 – the same year as the Plaza Flood.

The September flood was not exclusively a Plaza tragedy. The high water killed 25 people across the metro area, with victims recovered from Leavenworth to Leawood to Independence – and the Plaza.

The water that came out of Brush Creek damaged 77 of the Plaza’s 155 businesses – including what was by then the King Louie Plaza Bowl.

The annual Plaza Art Fair went forward, this time moved to the west.

But the bowling alley lease expired in 1978.

The former Sears automobile service center, just across Nichols Road, soon would be remodeled into a small retail strip christened the Court of the Penguins.

Gucci, the international leather goods retailer, opened a branch there in 1979.

Nearby, on the north side of Nichols Road, operators of Muehlebach Thriftway grocery received a lease termination notice in 1980.

They moved to a smaller location on Jefferson Street, and apparel retailer Brooks Brothers opened a branch in the remodeled grocery space later that same year.

Next to that would stand a new Saks Fifth Avenue.

That opened in 1982, occupying the same space where Woolworth’s five and dime had stood for years.

Many long-time Plaza residents, many without cars and used to walking for their necessities, began wondering if their patronage still mattered.

“You can’t buy a dishpan on the Plaza,” one Woolworth customer told a Star reporter on the store’s last day.

This was different from Nichols’ original plan, which primarily served nearby residents.

By the early 1930s, several apartment towers on the south bank of Brush Creek east of the Wornall Road bridge were in place.

“Apartments were extremely important in Nichols’ planning,” Worley said.

That didn’t seem true by the 1980s.

Continuing the Fifth Avenue theme, horse-drawn carriage rides – like those available in New York’s Central Park – became a routine sight on the Plaza.

A Nichols Co. spokesperson insisted that the district’s transition to high-dollar retail had nothing to do with the flood.

In fact, the trend represented nimble thinking on the part of the Nichols Co., said Vicki Noteis, president of Collins Noteis & Associates in Kansas City and a former assistant city manager and planning and development department director.

“While other downtowns were using high-end retail to revamp their downtowns and get people to come back, downtown Kansas City didn’t move fast enough and the Plaza jumped on that trend right away,” she said.

It made sense for such stores to locate there, said Jay Nichols.

“The Plaza is so unique,” Nichols said.

“There was nothing like it in America and it just naturally attracted blue-blood retailers.”

It also attracted high-rise office developers.

The ‘Bowl Concept’

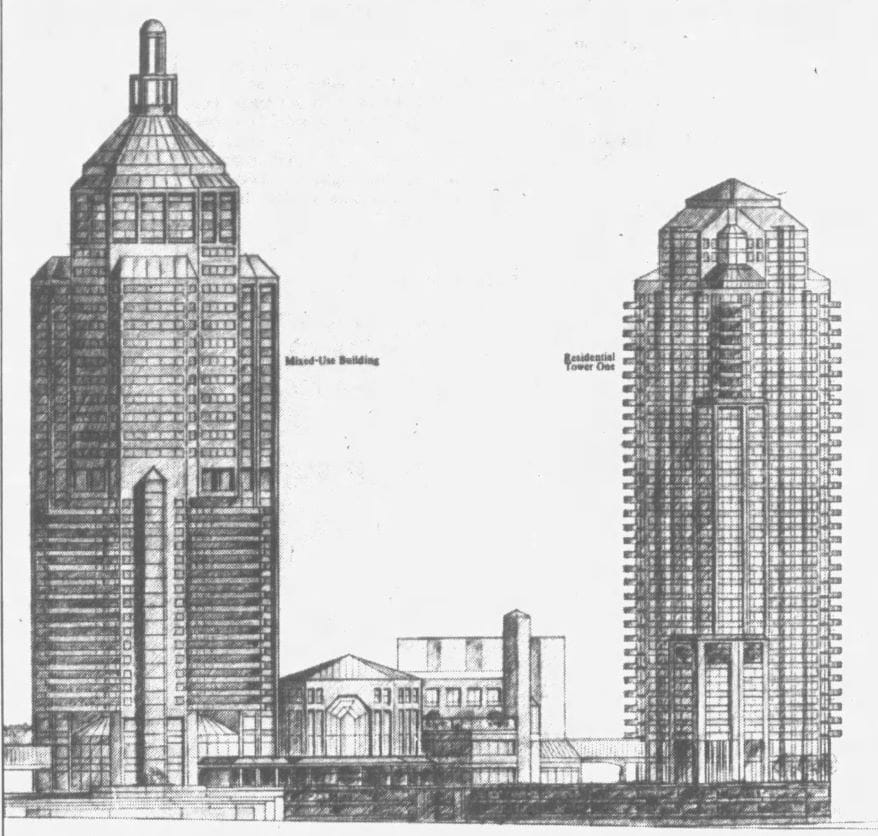

Since the 1980s, three principal planning battles – in 1984, 2010 and 2022 – have been fought over the scale of high-rise development in or near the Plaza.

What did J.C Nichols want in 1922?

Congestion, he told the Star that year, “has a direct relationship on the height of buildings.

“I believe one-story heights will not only serve traffic needs, but will add much to the comfort and convenience both of the patron and the merchant. Light, air and sunshine will be available to every shop window, thereby providing pleasant shopping conditions.”

That concept generally remained in place for the first 60 years of the Plaza’s existence, until a dynamic change prompted tension that continues to be fought over today. How can the Plaza’s historic charm be preserved in the face of developers who want to place high-rise buildings on a scale that they believe makes financial sense?

The first battle was over the Sailors project, proposed in 1984.

The $300 million business and residential complex, including six office and residential towers ranging in height from 11 to 53 stories tall, was to be built on the eastern edge of the Plaza, just southeast of Winstead’s restaurant.

Although it was not to be built inside the actual Plaza that Nichols had designed, critics found it profoundly out of touch with what Nichols had built.

“And, of course, the arguments were out of control,” said developer Ken Block.

“It was going to destroy the Plaza, it was going to destroy the whole world,” said Emanuel Cleaver, then a Kansas City Council member.

“Children would never eat again, and horses won’t run. It was a horror story.”

The plan met fierce resistance and was never built as originally announced. But it proved a valuable lesson, said Noteis.

“What that showed was that the Plaza was actually pretty vulnerable to major development that’s too big or too massive for an area,” she said.

Various neighborhood groups, Block added, banded together to fight it.

Part of the issue, Noteis added, was that the Plaza “was part of a neighborhood.” It wasn’t a place, like so many in Kansas City, where someone drove to park, walk around, shop and drive back to the suburbs.

“That’s partly why people felt strongly about it,” she said.

But one of the controversy’s legacies was the 1989 Plaza Urban Design and Development Plan, which called for taller buildings to be located on the perimeter of the Plaza in a “bowl concept” that would restrict the height of buildings in Nichols’ original development.

That plan, however, was only an advisory plan.

The planning debate flared again in 2010, this time involving the 1925 Balcony Building on West 47th Street.

This proposal submitted by Highwoods Properties, the North Carolina office developer which had acquired the Plaza in 1998, called for the demolishing of the Balcony Building – with its clay tile roof and terra cotta detail and two Spanish style decorative towers – to build an eight-story glass-dominated office tower that would be occupied by Polsinelli Shughart, a longtime Kansas City law firm.

Reaction was fierce.

Some 15,000 people signed a petition opposing the plan.

The law firm eventually moved into a separate building on the Plaza’s west end.

But that’s not half of it, Block said.

While visiting the Highwoods officials, he asked what other Plaza sites they were considering developing.

“And they said ‘Well, we have this one. We’re thinking about knocking down the Classic Cup.’

“I said ‘Uh, oh.’

“I said ‘That may be worse than the once you are proposing across the street.’

“That would have been like the sword in the throat. I think they just didn’t understand how many people believe the Plaza is theirs.”

In 2016, during Sly James’ term as mayor, the city adopted the Midtown/Plaza Area Plan. It further articulated the development recommendation known as the “Bowl Concept,” which held that low building heights should be maintained in the core of the Country Club Plaza, while the height of proposed office and residential buildings could increase as they were located farther away from that original shopping district.

In 2019, Kansas City officials approved a zoning overlay that would regulate the height of building projects considered part of the Plaza.

This past May, after months of controversy, the Kansas City Council approved a three-story restaurant project called Cocina47 on the site of the site of the Seventh Church of Christ, Scientist, on West 47th Street. The original proposal called for a nine-story restaurant and housing project with no on-site parking.

The church will be demolished for the project, projected to be completed by 2025.

It’s part of a continuing dialogue.

“It’s probably the most controversial issue we have dealt with in Kansas City – high-rise development at the Country Club Plaza,” Mayor Lucas said.

Ownership Turmoil

In 1998 Nichols Co. shareholders approved a $544 million merger between Nichols Co. and Highwoods Properties Inc., a North Carolina real estate operator of suburban office and industrial properties.

The vote, which included approval by the holders of more than three-quarters of Nichols Co. shares, ended more than 90 years of local ownership.

The vote also ended over three years of turmoil concerning the company’s future and that of the Country Club Plaza.

In 1988 longtime Nichols Co. executive Lynn McCarthy had assumed control of the company while Miller Nichols, who had headed the country since 1950, stepped down as chairman but remained as director.

At the time, the Nichols Co. established an employee stock ownership trust, or ESOT, to buy out the interests of the founding Nichols family.

The trust borrowed close to $100 million to finance the transaction. The debt was supposed to be repaid from tax-deductible contributions made by Nichols Co. to the trust.

But then the Nichols Co. sold its hotel division in 1989, reducing its payroll from 1,200 employees to 300.

That, in turn, reduced the contributions it could make, leaving the trust with a debt it was unable to pay.

In 1992 a McCarthy-led partnership stepped in and assumed the trust’s debt for a 65% ownership stake in the Nichols Co. without paying any money, according to news reports at the time.

Further, McCarthy never made any debt payments – but did collect close to $4 million in dividends on the Nichols Co. stock he had acquired.

In 1995 McCarthy was ousted as company chair amid claims of conflict of interest. Nichols resigned as a director several weeks later.

As part of a 1995 settlement approved by a federal judge, McCarthy gave back to Nichols Co. land and stock he obtained in transactions some shareholders contended had helped him at the company’s expense.

McCarthy pleaded guilty in 2001 to a count of racketeering conspiracy. He admitted he conspired to defraud the Nichols Co. of more than $150 million. He was later sentenced to five years’ probation. He died in 2019.

But the company’s various debts and losses incurred before and during the legal skirmishing likely contributed to the Nichols Co.’s decision to merge with Highwoods Properties, said Dan Margolies, a Kansas City journalist who covered the discord for the Kansas City Business Journal and the Kansas City Star.

“Long story short, all this eventually led to the acquisition of Nichols by an outside company,” said Margolies.

“The founding family was basically in control of the company until that settlement with the ESOT,” Margolies added.

“But after the settlement, the ESOT held the largest stake in the company and was able to determine what the company should do, and that is basically what happened.”

What might have been beneficial for Nichols Co. shareholders may not have been good for the Country Club Plaza, said Jay Nichols, a grandson of the company’s founder.

“While it was very advantageous to the family in the short run, I think it was a real mistake for the family to sell the Plaza,” Nichols said.

“Highwoods were not good owners. They were office building people with absolutely no feeling for retail.”

Uncertain Future

If Kansas City residents believe the Country Club Plaza is theirs, now – as they await that annual November display of holiday lights – would seem a suitable time for them to decide what the Plaza’s future should look like.

That discussion has already begun, in part due to someone from outside the community.

In 2019 Kansas City artist Chico Sierra sat down at his keyboard, logged onto an online petition site, and suggested that J.C. Nichols’ name be removed from what then was J.C. Nichols Parkway.

The act, he wrote, would reflect “our collective duty toward restitution and healing.”

Sierra made the proposal in context of the then-ongoing community dialogue regarding whether the Paseo should be renamed to honor Martin Luther King, Jr.

Many online residents responded favorably to Sierra’s idea.

Meanwhile, the Kansas City Council had voted to rename the Paseo after King, and signs had gone up before residents voted to restore the original name.

Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas then directed the parks board to engage the public as to how to best honor the civil rights leader. Over the next year the board held several public meetings and invited suggestions before choosing, in 2021, to rename a stretch of road incorporating Volker Boulevard, Blue Parkway and Swope Parkway in honor of King.

Today Sierra would welcome a similar public exercise to reframe and refocus the Plaza’s future going forward.

Having grown up in El Paso, Texas, before moving to Kansas City some 15 years ago, Sierra has studied the community’s history and wonders if the Plaza is part of an old order that is rapidly fading.

A successful future for the Plaza, Sierra said, would have stakeholders conferring on “a complete redefinition of the area – what it should be and what they want it to be.”

The Plaza’s operators, both current and future, he said, “need to be more community-oriented, and I don’t see that happening.”

The Plaza, added Gwendolyn Grant, is “still one of our gems. I hope we can write a different future.”

Whatever business entity directs the Plaza moving forward will need to attract a more diverse base of patrons, she added.

“My view of the world is of one that is becoming much more racially and ethnically diverse, and we need to embrace that diversity,” Grant said.

“Irrespective of your personal views on race or racism, it makes darn good sense to be inclusive, to welcome people from all walks of society, and create inviting spaces.”

Others expressed similar sentiments.

“It’s time for the Plaza to take off its tuxedo,” said Emanuel Cleaver.

“It needs to put on a hoodie,” added Chris Goode.

More seriously, Goode said, “It’s time for a new branding, an honesty check.”

In 2020, during the George Floyd demonstrations, he didn’t believe J.C. Nichols was a historic figure that should be honored by a public fountain or parkway.

“So, I drove that issue along. I voiced my concerns to my fellow board members, finally getting the approval of even his own family,” he said.

Cleaver believes the removal of Nichols’ name was an act of important civic symbolism.

“It’s an effort by the city to say that we are not the same city,” he said.

Stakeholders also should be discerning in how they may weigh Nichols in the balance and find him wanting, at least according to contemporary standards, said Sly James.

“J.C. Nichols built this really neat thing on the Plaza,” James said.

“I think you can have people who do good things and also do bad things. We can honor them for the good. I don’t think we need to honor them for the bad.”

The Plaza also needs to tell a more Kansas City story, added Elizabeth Rosin.

The district, she said, feels “not populated by Kansas Citians. There’s no draw for me. And that makes me sad.”

One believer in the appeal of local retail tenants is Tyler Enders, one of the founders of Made in Kansas City.

The firm works with more than 200 local artists and small business owners, and showcases local gifts and clothing at several locations, among them a Plaza store on West 47th Street.

“There’s a personability to local retailers that makes our community more vibrant and simply more pleasant,” Enders said.

“Of course, shoppers will want more of that at the Country Club Plaza. They aren’t going to the Plaza to buy things they can order online. They’re going for the one-of-a-kind experience with subtle surprise and delight moments around every corner.”

Enders is currently a member of the Kansas City Plan Commission, which will consider proposals for future development on the Plaza as new owners come into town, the streetcar extension is completed and other developers present plans nearby.

That seems timely to Vicki Noteis, who believes the Plaza needs an advocate.

“It needs an advocate at City Hall,” she added. “Everybody still talks about (the Plaza), so I don’t think that’s going to be a problem.

“It’s a big discussion.”

Finally, if Kansas Citians still feel the Plaza belongs to them, it follows that the Plaza should be considered a family heirloom and treated accordingly, said Jay Nichols.

“I know that the family still doesn’t own it,” Nichols said.

“But I feel that it’s our gift to Kansas City.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016. Emily Woodring is a multimedia producer at Kansas City PBS. Cody Boston, Julie Freijat and Dominick Williams contributed photos and visualizations.

More on Flatland

Country Club Plaza Backers See Silver Lining in Loan Default A loan default by the owners of the Country Club Plaza has lifted the hopes of Plaza advocates about the future of the venerable shopping district.

Texas Investors Eye Purchase of the Country Club Plaza A Texas firm that owns the luxury Highland Park Village shopping center in the Dallas area has a tentative agreement to acquire the Country Club Plaza.

Prospect of New Country Club Plaza Owners Sparks Optimism News that the owners of Highland Park Village in Dallas may buy the Country Club Plaza garnered generally positive reactions from Kansas City residents.

Tags: Country Club Plaza • development • J.C. Nichols • J.C. Nichols Co. • Kansas City • Nichols' Folly

Like what you are reading?

Discover more unheard stories about Kansas City, every Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!

Check your inbox, you should see something from us.

Ready to read next

Whew!