‘Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City’: New Book Offers a History of Kansas City Eats A Feast of Local Food Heritage

Published July 6th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

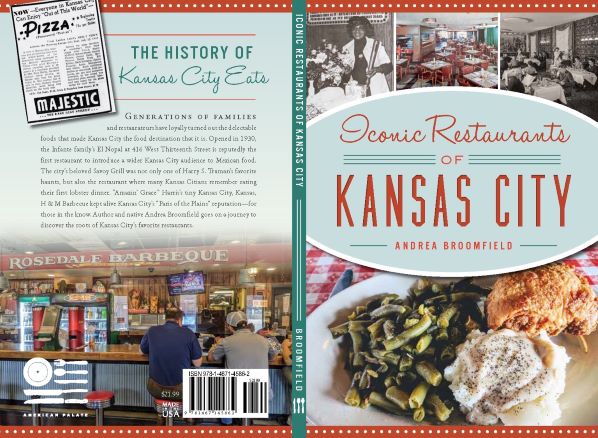

Above image credit: A postcard depicting Putsch’s 210, circa the early 1950s. (Courtesy | Andrea Broomfield)Arthur Bryant’s Barbeque stands today as one of Kansas City’s most iconic eateries, but our culinary claim to fame extends far beyond our famed “grease houses.”

A ghostly array of long-shuttered taverns, roadhouses, cafeterias, lunch counters, burger shacks, diners and steak houses have played a role in shaping our collective taste buds. These “lost” restaurants were independently owned eateries that existed for at least three or four generations.

“You build a cuisine — a food heritage — by religiously making the same foods to the same standards over and over,” says author Andrea Broomfield, an English professor at Johnson County Community College and the author of “Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City” (History Press).

A sampling of iconic restaurants includes:

The Green Parrot Inn, located at 52nd Street and State Line Road in Shawnee Mission, Kansas. The inn had its run from 1929 to 1955. The menu featured scratch home cooking by Tena May Dowd, whose most popular dish was fried chicken. Dowd was also a prominent supporter of “dry Kansas.”

“If Kansas City sometimes claims the fried chicken dinner as its own contribution to American good eats, that claim rests largely with Dowd’s efforts and her definition of wholesome food made better with a tall glass of iced tea,” Broomfield writes.

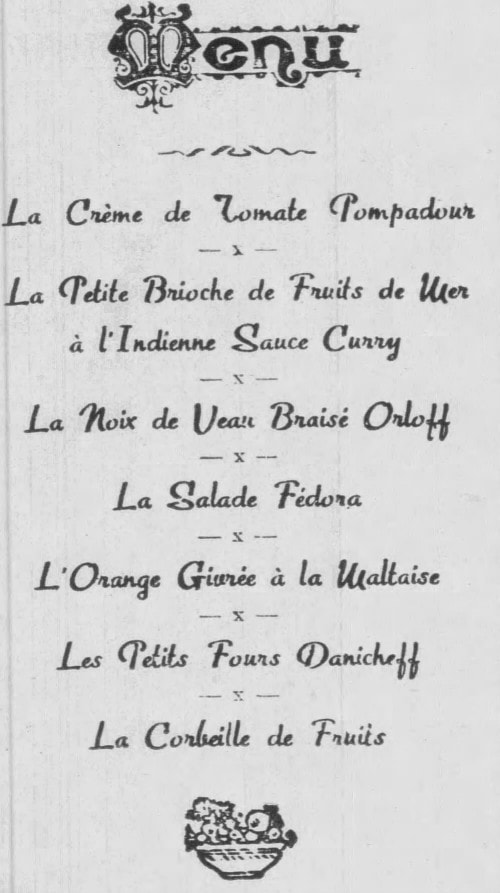

Putsch’s 210, which opened in 1946, “epitomized fine dining on the (Country Club) Plaza. Its service, lighting, soft live music and tableside cooking were carried out with graceful exactitude,” Broomfield writes.

“Although the restaurant closed in 1973, Putsch’s 210, with dress code, strolling violinist and tableside cooking, signified for Kansas Citians the passing of an era that they would reminisce about for the rest of their lives.”

El Nopal, 416 W. 13th St., was run by the Infante family from 1930-1966 and considered “the area’s first restaurant to consciously introduce a wider Kansas City audience to Mexican food,” Broomfield writes.

“While it would be impossible to pinpoint how the ‘Kansas City’ taco came to be, folding seasoned ground meat into corn tortillas, tooth-picking them shut, and deep frying them, that was precisely how the Infante family prepare their tacos,” according to Suzanne Infante Lozano, who is the daughter of the owners.

Ruby’s Café (1506 Brooklyn Ave. 1952-2001) and Maxine’s Fine Food’s (3041 Benton Ave., 1962-2003). Both owners were known for soul food and their contribution to race relations through segregation and beyond.

“There was a lot out there about Ruby (Watson McIntyre), but there was a lot of contradictory information. Piecing together her story was really interesting,” Broomfield says during an interview with Flatland. “Also, Maxine Byrd of Maxine’s Fine Foods … Both have a lot to do with race relationships … (and operated places) where people could come and talk about issues of race over hotcakes.”

Picking and choosing which restaurants to highlight was tricky.

“Restaurants are loved, until they are gone,” says Broomfield, who is a Kansas City native. “While they are there, no one is thinking of archiving the menus. They’re too busy operating the business, so piecing together their stories can get really hard.”

History Run Amok

If it’s true that journalism is the first rough draft of history, Broomfield acknowledges her reliance on reporting by many local food writers (including this author). She even considered dedicating “Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City” to the late Charles Ferruzza, longtime restaurant critic for The Pitch.

“He never treated that job as just being a restaurant critic,” Broomfield says. “He was always trying to get some of the history: The importance of where a restaurant was located? What kind of neighborhood was Waldo? Who were the people who owned this restaurant before this family? He was always searching for those pieces of information, more so, I thought, than other food writers.”

Broomfield was especially fascinated by Ferruzza’s enthusiasm for the Bamboo Hut Restaurant & Lounge, which was open from 1942-2010 and “a crazy interesting story.”

The roadhouse “of questionable reputation” was located at 40 Highway and Pittman Road (now 10111 E. U.S. 40). When brawls broke out, jurisdiction was muddled between Kansas City, Missouri, and Independence law enforcement.

By 1980, the tiki interior had gone up in flames but gave way to a décor Ferruzza described in a review as “1960s rec room.” Still, Bamboo Hut continued to serve stiff drinks, added huge steaks, and remained a venue where “smoking and cholesterol have never gone out of style” until 2010.

Unfortunately, Bamboo Hut did not make the cut, but the complete story can be found on Broomfield’s blog (andreabroomfield.com).

Chasing Breadcrumbs

The COVID-19 pandemic initially thwarted Broomfield’s work on the manuscript. When libraries, research archives and restaurants shut down, she was forced to rely on ancestry.com and newspapers.com.

As she started to write, Broomfield ignored the 45,000-word count because she didn’t want to choose her entries based on length of the manuscript. She had many entries that did not ultimately make the cut, but she wound up convincing the publishers to give her 3,000 more words, at the expense of color photography.

“What matters to me is that we have an authoritative history of Kansas City restaurants,” Broomfield says. “People wanting to take a trip down memory lane, that’s fine, but I’m writing this book for people who can continue this work. Ideally, 20 years from now, there’s a much better history of Kansas City food than what I have done.”

Her most frustrating near miss?

Broomfield was eager to hunt down information about the reasons behind the closing of La Bonne Auberge, a French fine dining restaurant in a strip mall in the Northland that gained popularity in the 1970s through the mid-’80s.

The restaurant was founded by the late Swiss chef Augustine “Gus” Riedi, whose protegés included Susan Feniger of The Food Network’s “Too Hot Tamales” fame and Kent Rathbun, who grew up in Liberty, Missouri, and went on to own prestigious restaurants in Dallas.

When Broomfield couldn’t verify the circumstances of the restaurant’s closure, she chose to profile La Mediterranee, a premiere French restaurant of the 1990s, instead.

“One of the most important things I learned is when you have a restaurant, it’s like a part of your body,” Broomfield says. “It’s like an appendage, and when something goes bad with your restaurant, it hurts, and people don’t want to talk about it.”

Supporting Local

There is, of course, a chapter titled “Barbecue & Steakhouses.” But it was the fine dining chapter that captured the attention of a British food journal.

From the 1940s to 2000s, most fine dining occurred in hotels in the earliest days of Kansas City history. Over the past 20 years, stand-alone restaurants (including Bluestem in Westport, which closed during the pandemic but missed the manuscript deadline) have taken the lead.

“I think we have a lot of upscale dining in Kansas City, we’re just not dressed up for it. My guess is they may make a comeback because people are sick and tired of noise, talking over loud music, exposed walls,” Broomfield says.

“There is a place for a Putsch’s 210, and somebody is going to come along and do it. Meanwhile, we have a level of restaurants that have a high level of cuisine,” she adds.

Broomfield met to discuss her book at Revocup Town Center, noting that the locally owned coffee shop was tucked into a shopping center dominated by national name-brand chains.

“It strikes me as the biggest challenge and the biggest tension in recent restaurant history is: How do you maintain a distinctive food identity when you are encroached upon by these huge chains that soak up all the real estate?” she says.

Ultimately, Broomfield hopes Kansas City diners who read her book understand the importance of celebrating and supporting independently owned restaurants.

“I want people to have a conscious sense of what makes Kansas City food distinct. And ultimately, that (readers) stop and think about what it means to have a food city,” she says. “A lot of people are just not conscious of this issue, and why would they be … They like Bonefish Grill because it has a great vibe. But if you are supporting Bonefish Grill, then what are you not supporting?”

Jill Wendholt Silva is a James Beard award-winning food editor and freelance writer. You can follow Silva at @jillsilvafood.

I look forward to reading the restaurant history book. Not knowing if it is in the book, my memory is La Bonne Auberge was located in the 70s in a high rise Ramada Inn on 6th near Broadway. I don’t recall if it left before or at the time the building was torn down. Also it may be in the book but La Mediterranee was located on the Plaza at the location of todays O’Douds. La Mediterranee moved to a strip mall near 91st and Metcalf before it closed. It was pure old world elegance with great food and service while on the Plaza.