Turn O’ the Century Kansas City Amusement You Asked, and We Went Back in Time

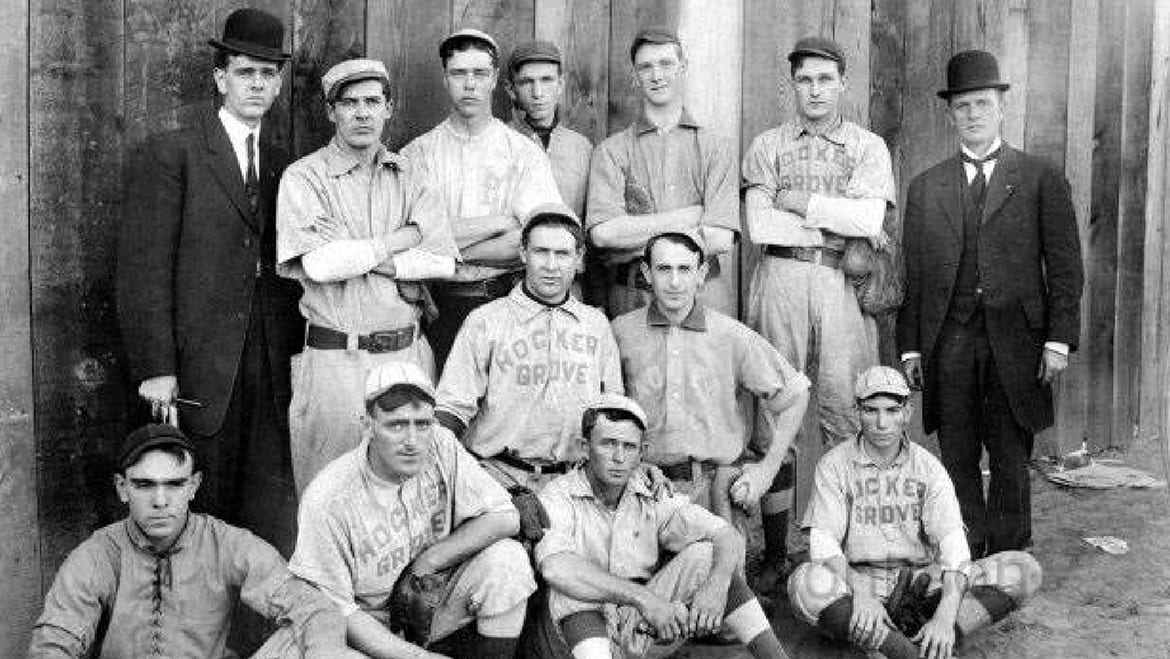

The Hocker Grove Baseball team poses at the baseball field in Hocker Grove Park in 1908. (Contributed | Johnson County Museum)

The Hocker Grove Baseball team poses at the baseball field in Hocker Grove Park in 1908. (Contributed | Johnson County Museum)

Published August 6th, 2018 at 6:05 AM

Nowadays, if you want entertainment, you don’t even have to leave your couch — seasons of “Friends” are just a Netflix log-in away. The more adventurous types can head to First Fridays or take a ride on the Mamba roller coaster at Worlds of Fun.

But what about a hundred years ago? What the shuttlecock did people do for fun?

Two Kansas Citians asked us about a couple prominent areas that existed to entertain and amuse during the turn of the century. Ruth Moore asked curiousKC, “What happened to the amusement park that was in Merriam, Kansas, around the turn of the century?” And Sally Firestone asked, “I have heard that Valentine Road was part of a racetrack, which would account for its curve. Is that true?”

Racetracks and amusement parks were all the rage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not unlike today. So, since you asked, we investigated, and read enough super-old, dramatic newspaper clippings for a lifetime.

While investigating Moore’s question, we discovered not one, but two pleasure parks that existed around the turn of the century.

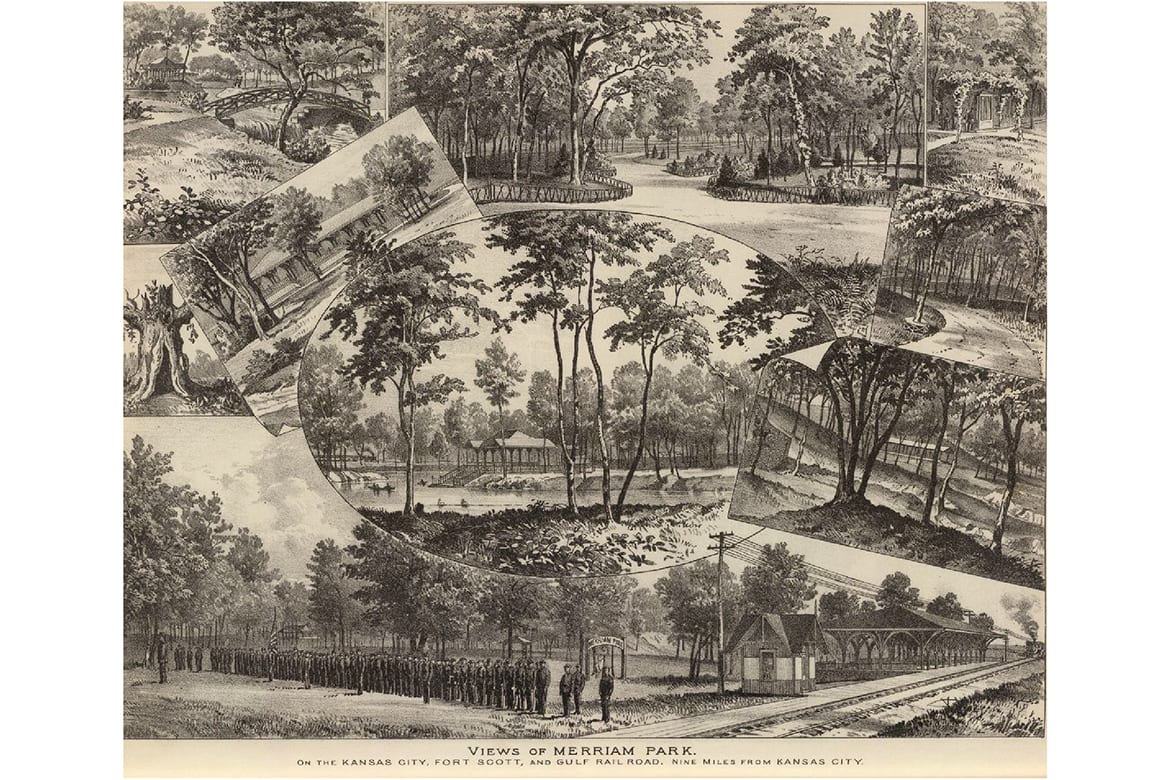

Merriam Park was established in 1880 within a “naturally beautiful grove” (The Olathe Mirror, March 18, 1880) off of the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Gulf Railroad line, eight miles from Kansas City. Like the city of Merriam, it was named after Boston native and treasurer of the railroad line, Charles Merriam.

Merriam Park was an uber popular place to picnic. Area committees, church groups and families visited often during the warmer months. Newspapers gushed over the park and its amenities.

“The Park is one of beauty, and a beautiful temple is erected on the grounds that will accommodate hundreds if not thousands. Plenty of water and shade, in fact everything necessary to make the visitor feel perfectly at home.” (The Olathe Mirror, June 24, 1880)

Former President Grant was on hand July 2, 1880, to help celebrate the park’s dedication. The event organizers were expecting a crowd of thousands in anticipation of what was sure to be “the grandest picnic gathering Kansas has ever seen” (Fort Scott Daily Monitor, June 27, 1880).

But that was all well before the rain came. A major thunderstorm turned dirt pathways to muddy waterways, and strong winds left “houses blown down…buildings unroofed and lumber yards demoralized” (The Topeka Daily Capital, July 5, 1880). Those who were able make it by train trudged a quarter mile through the mud just to reach Grant’s stand.

Almost every newspaper, even those from hundreds of miles away, reported on this occasion. Some barely mentioned the deluge, while others reported extensively on the inter-state drama that ensued during Grant’s visit.

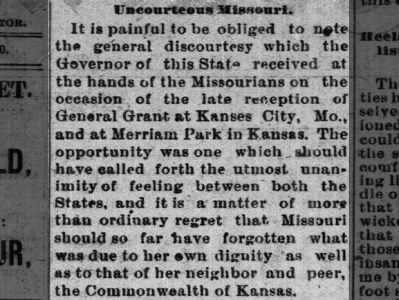

The governor of Kansas at the time, John St. John, was upset with how he was treated by Missourians. For one thing, he had to wait a few hours to meet Grant. And, a carriage was provided for the Missouri men, but not for St. John and his party. Kansas newspaper after Kansas newspaper criticized the Missouri party, illustrating that the ‘border war’ was still seething at the time.

The July 5, 1880, edition of the Topeka State Journal recounts animosity between Kansas Gov. John St. John and Missourians at Merriam Park.

(Kansas Historical Society | Newspapers.com)

Following the publicity (and drama) from Grant’s visit, Merriam Park’s 40 acres continued to add more and more entertainment. For 25 cents, you could visit the park’s zoo and see bears, a lion, monkeys and other animals, ride the horse-drawn merry-go-round, boat or skate on the pond, or play at the baseball diamond, tennis courts or croquet grounds.

The park closed in 1900 amidst competition from other entertainment options in Kansas City. But, Merriam wasn’t out of amusement or a local picnicking place for long.

In 1908, real estate developers Richard Weaver Hocker and O.M. Blankenship built Hocker Grove Park along the Hocker Grove Electric Trolley Line that ran through Merriam to and from Kansas City.

“This amusement park featured roller-skating, dancing under a large pavilion with a Wurlitzer automatic band organ (the pavilion doubled as a basketball gym), and was the site of balloon ascensions, professional boxing matches, and picnics. Families rode the Hocker Line from Kansas City to enjoy picnics in the natural setting,” according to a blog post from the Johnson County Museum.

Like Merriam Park, the 40-acre Hocker Grove Park also came with its own dose of drama. Law enforcement often arrested people who were either selling whiskey from Kansas City or drunk. A 14-year-old girl and her father were found living in a “hut” in the park. She was sent to juvenile court, convicted as “incorrigible” and sent to an industrial school, according to the Topeka Daily Capital on August 21, 1908.

Attendance dwindled as ridership on the trolley line diminished, the park closed shortly after the death of Hocker in 1919.

In 1919, Hocker Grove Park closed to become a residential area that still bears the park’s name. Use our juxtaposition tool from the Knight Lab to compare the renderings from 1922 to what it looks like today. (Johnson County Museum, Google Maps | Knight Lab)

During the turn of the century, Kansas Citians across the state line had their own amusement parks, too, but with a little something different: horse racing.

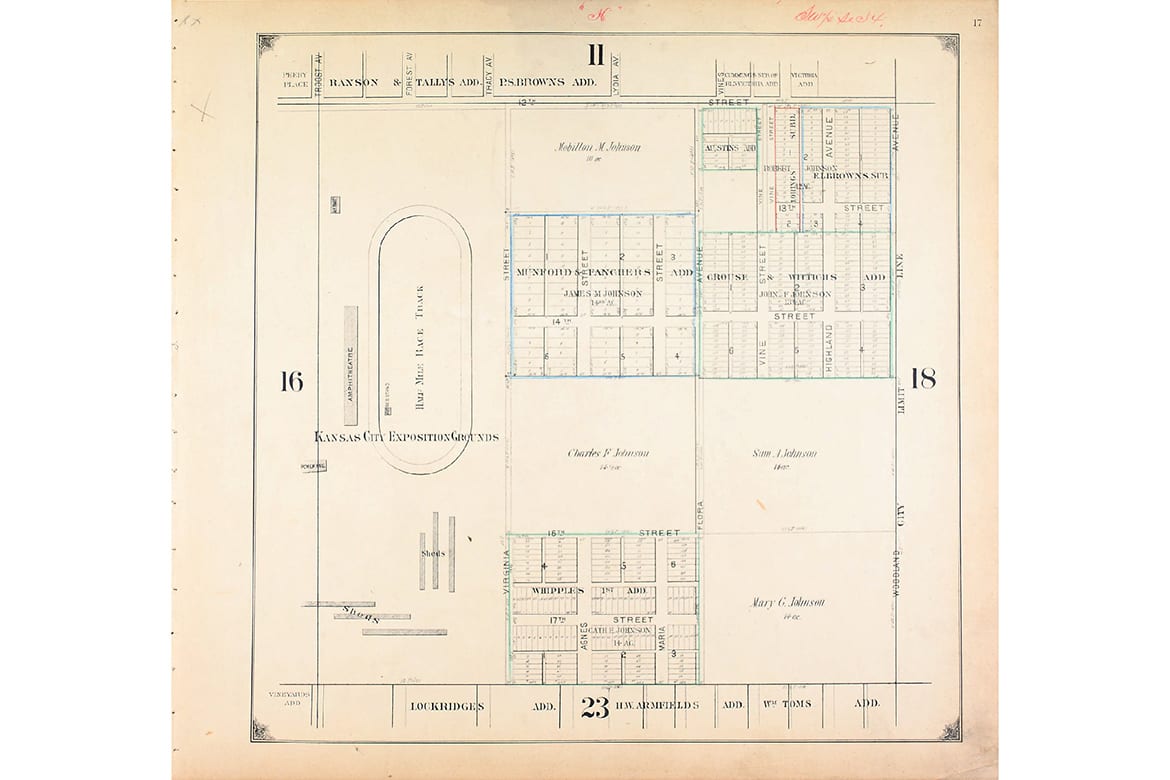

The Kansas City Interstate Fair and Exposition attracted thousands in the 1880s, and existed in the area near Roanoke Park where the residences of Valentine Road are today. The most infamous part of the Exposition’s existence was its racetrack.

“The half-mile racetrack stretched from what is now Valentine Road south to 38th between the west side of Pennsylvania and Summit Streets,” the Midtown KC Post said in an article.

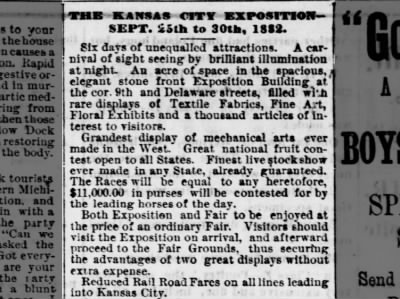

The Sept. 14, 1882, edition of the Osage County Chronicle promotes the upcoming Kansas City Exposition. (Kansas Historical Society | Newspapers.com)

The Kansas City Interstate Fair and Exposition wasn’t Kansas City’s first fairground. Kansas City’s initial expositions featured artists, manufacturing and industrial devices, and horse racing. Jesse James and his band of masked men infamously robbed the second exposition in 1872, stealing $978 from the ticket booth.

The Kansas City Interstate Fair and Exposition grounds gradually gave way to residences in the late 1880s. The annual fair and exposition wasn’t lost however, and was relocated between 12th and 15th streets.

—

Special thanks to Amanda Wahlmeier, Local History Librarian at Johnson County Library, and Andrew R. Gustafson, Curator of Interpretation at Johnson County Museum Arts & Heritage Center, for all of their help to answer Sally and Ruth’s questions.

Rachel Thomas is a summer engagement intern for Kansas City PBS. She’s studying convergence journalism at the University of Missouri.