Rural and Hungry Beyond the Urban Core, Kids Struggle For Meals When School’s Out

Published August 6th, 2018 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Kristen Hanks, who works in the Fire Prairie Upper Elementary School cafeteria, hands out lunches at Susquehanna Baptist Church in Independence, Missouri, a government-funded summer meal site. For children in the Kansas City metro area, food insecurity rises in the summer, but food sites like these are rare in rural areas. (Lindsay Huth | Flatland)The rush hits at noon. That’s when kids start pouring into the gym at Susquehanna Baptist Church. On a scorching Wednesday last month, they lined up to choose their lunches: pizza, subs or PB&J. Most picked pizza.

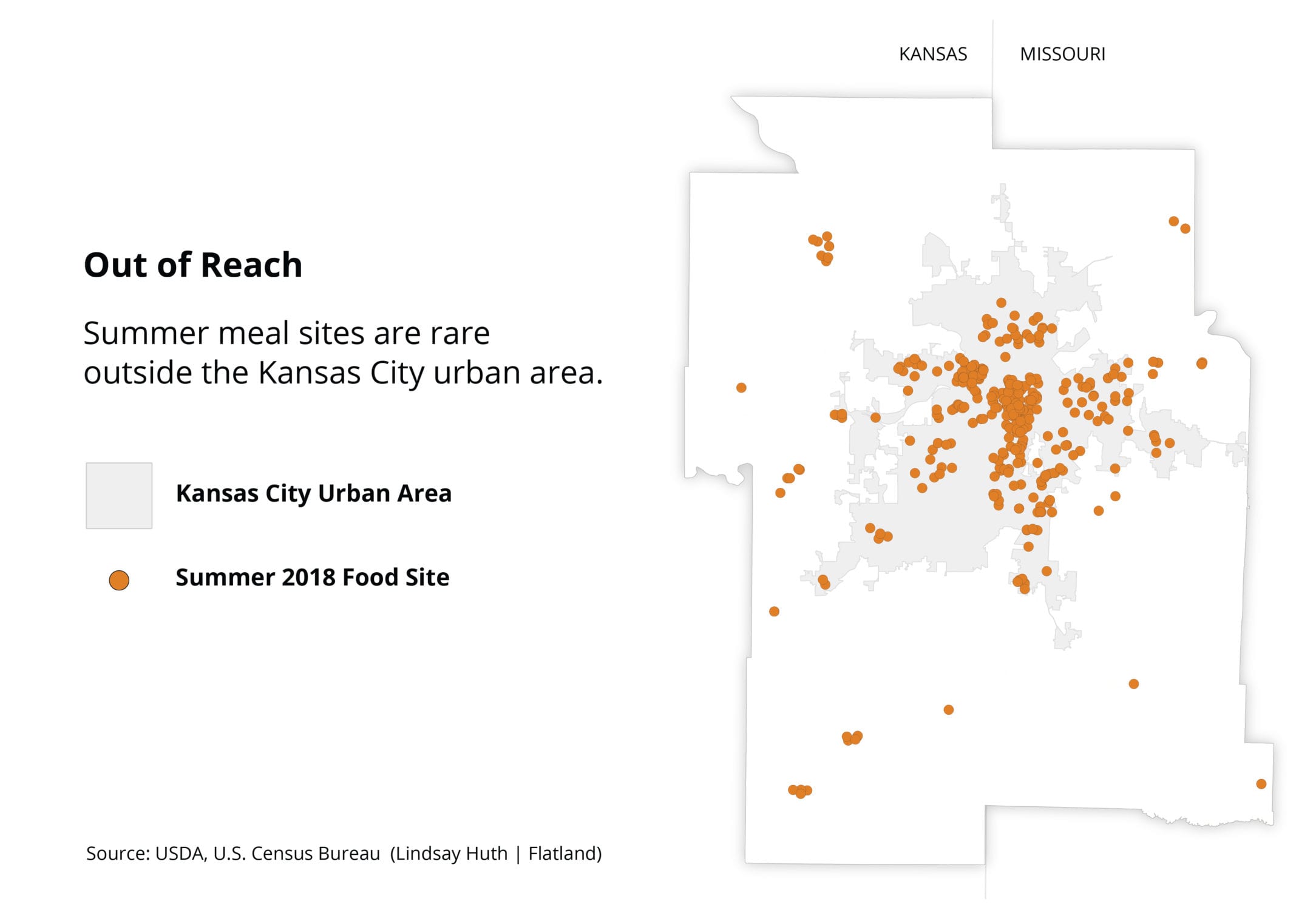

The Independence, Missouri, church is one of more than 350 summer food sites around Kansas City that provides meals to kids who rely on free or reduced-price lunch during the school year. But not all kids can get to a food site.

“Summer is the time when food insecurity and hunger spike for families because they lose access to free and reduced-price lunches and breakfasts during the school year,” said Crystal FitzSimons, director of school and out-of-school time programs for the Food Research & Action Center.

Two government-funded food programs work to feed low-income kids over the summer. But they require kids to travel to sites daily for meals, making it difficult for kids in rural areas. And federal regulations limiting where food sites can operate leave wide stretches of those rural areas ineligible to serve meals.

The majority of sites in our eight-county region — comprising Johnson, Leavenworth, Miami and Wyandotte counties in Kansas and Cass, Clay, Jackson and Platte counties in Missouri — are currently focused on the urban core. A mere 13 percent of sites serve kids outside of that densely packed metropolitan center.

That’s just one site for every 100 square miles in rural areas, compared with 45 sites per 100 square miles in urban areas.

The sites might not exist, but the need does.

FitzSimons said getting meals to every kid during the summer is unrealistic. But last year, Missouri and Kansas served summer meals to fewer than 1 in 10 kids who received free or reduced-price lunch during the school year.

“Kansas and Missouri are pretty rural states, and so they do struggle with transportation to the sites,” FitzSimons said. “But at the same time, rural kids need to have care during the summer.”

Rural and Out of Luck

No summer food sites operate in the Platte County R-3 School District, which encompasses Platte City, Ferrelview and Hampton, Missouri. But the district has hungry kids: It serves free or reduced-price lunch to a quarter of its students during the school year, said Jen Beutel, executive director for pupil services.

“Would I love to be able to feed kiddos all year? Yeah, I would,” Beutel said.

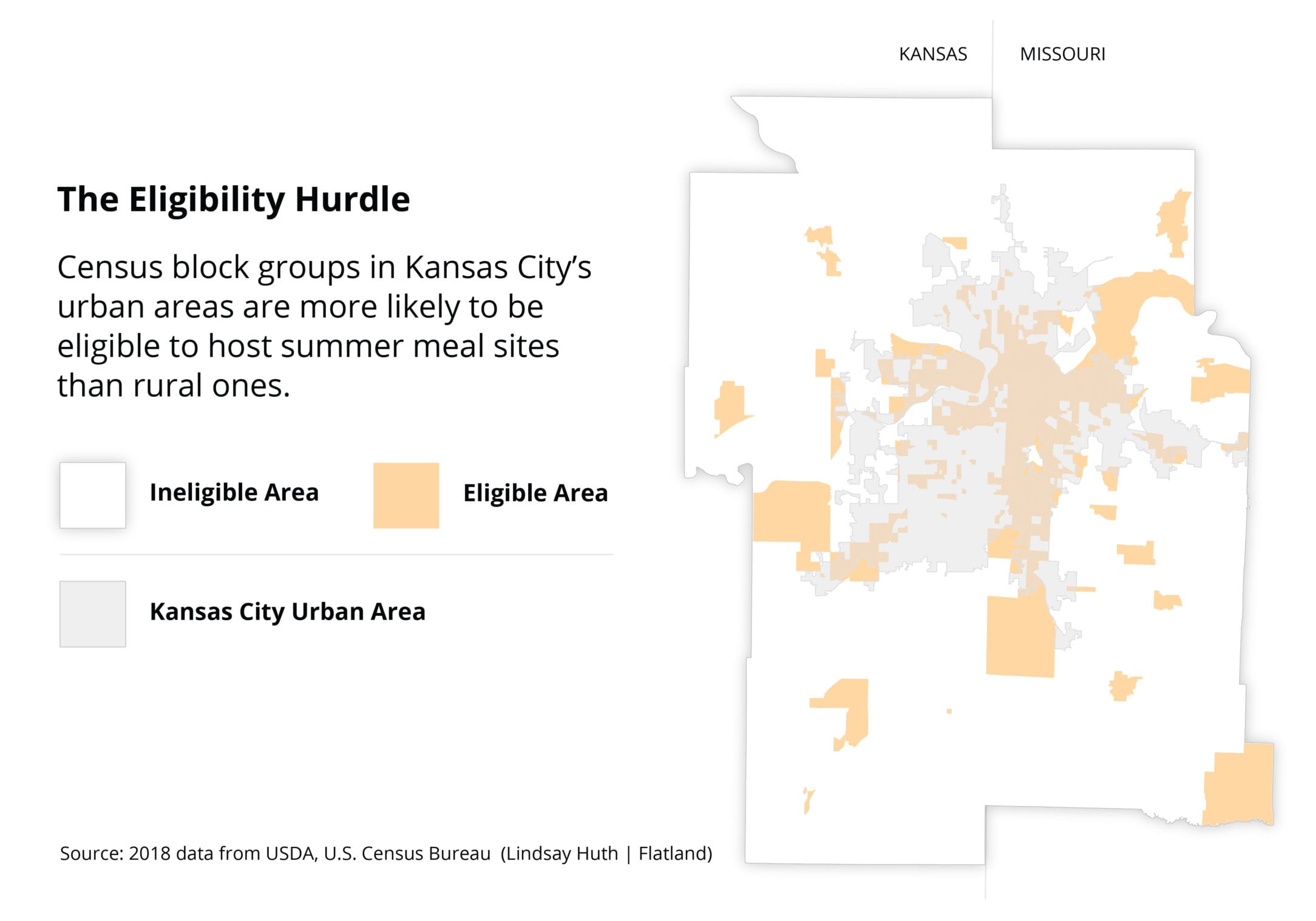

Nearly all of Beutel’s district is ineligible to host food sites.

The two government programs, the Summer Food Service Program and the National School Lunch Program’s Seamless Summer Option, qualify sites through need.

One of the most common ways for a site to demonstrate need is to be located in a census block group — a government-defined area containing 600 to 3,000 people — where at least half of the kids are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch during the school year.

Yet that cutoff means, in the Kansas City region, nearly 3,200 square miles of our 3,850 square miles are ineligible to host sites.

Sites are also eligible to serve summer meals if they are located in the attendance area of a school where half of the students enrolled during the regular school year can receive free or reduced-price lunch.

Sometimes states can even be flexible about which month’s school lunch data they use, said Kevin Gorsage, director of school nutrition programs at the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

The other ways to be qualified are less straightforward. Sites can average several contiguous census block groups to meet the threshold or use data from a specific program, like a summer camp, to show need.

“If there’s a community that feels that, ‘Hey, we really have identified this pocket of poverty in our community,’ there are ways to work to get the sites qualified,” said Kelly Chanay, assistant director for child nutrition and wellness at the Kansas State Department of Education.

Across the region, 1 in 4 kids eligible for free or reduced-price lunch during the school year lives in an area unable to serve summer meals.

Data show that just 6 percent of ineligible areas used alternative criteria to host a site this year.

Angela Currey, assistant superintendent of special programs in the Kearney School District, understands the challenge that ineligibility presents.

“It’s hard when you don’t meet that percentage of free and reduced lunch to qualify for the additional food programs,” Currey said.

Currey’s district is located in Clay County, centered in a town of less than 10,000. Nowhere in the district is eligible to serve summer meals. But in one of its census block groups, 47.6 percent of kids are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, just shy of the 50 percent threshold.

Currey said Harvesters’ BackSnack program distributed more than 500 packs of food in her district last school year, and the homeless population in her district has grown tremendously in the last three years. For now, the school district directs families to the Kearney Food Pantry.

“We know that there’s a need,” she said.

How should needy kids living in ineligible areas get food? Tanya Harvey, summer food service program manager for Missouri, said there is “not a good answer for that at this time.”

Both summer food programs are federally authorized and funded; the state agencies simply implement those plans.

“Right now we can only do what USDA allows us to do,” she said.

‘A Grand Experiment’

The USDA acknowledged in a 2011 report that its summer food programs leave large segments of the country without access to meals.

In 2011, the department began piloting Summer EBT for Children, one of the largest-ever tests conducted to evaluate a new model for reducing childhood hunger, according to a departmental report. Kansas City belonged to the original cohort of cities testing the program.

About 1,500 households were randomly selected from three participating school districts: Kansas City, Center and Hickman Mills. Rather than distributing meals from predetermined sites, the program offers families additional food stamp benefits, which they can redeem during their regular grocery shopping.

“The idea is to distribute it in places where there’s limited access to summer food sites,” said FitzSimons, the Food Research & Action Center director.

Kansas City has operated the program each year since, except 2014, when the number of participating cities was scaled back due to lack of funding. In Kansas City and other participating Missouri locations, families redeemed more than 90 percent of their benefits each year. Kimberley Sprenger, who oversees the program for the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, said the state has “an extremely high redemption rate.”

She said the state reapplies to the USDA annually for grants to conduct its test locations, so the future of the program in Missouri is unclear.

USDA reports show that the program decreased the frequency of severe food insecurity among participating children by more than a third when compared to a control group. It also improved kids’ nutrition, increasing their intake of fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

Though the local school districts testing the program are all urban, the USDA has since begun piloting the program in rural Missouri, including Mississippi, Shannon, New Madrid and Pemiscot counties.

For rural kids struggling to reach existing summer food sites, Summer EBT for Children is a “really effective and efficient way to overcome that problem,” said Jonathan Barry, director of No Kid Hungry Missouri.

“I am hopeful that that model will be adopted nationwide as a way to more efficiently provide families with resources during the summer,” he said.

“In some ways, it was a grand experiment back in 2011,” said Brent Schondelmeyer, deputy director for community engagement at Kansas City’s Local Investment Commission, which administers the program locally. “And the results came back strong and favorably, and the question is: Is there the capacity — political capacity, political will, fiscal will — to sort of expand this and make this available?”

— Lindsay Huth is a data reporting intern for Flatland and a journalism master’s student at the University of Maryland, College Park. Previously, she studied visual communication design and psychology at the University of Notre Dame.