KC Filmmakers Tee Up Documentary on Black Golfers Drive for Inclusion

Published July 8th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

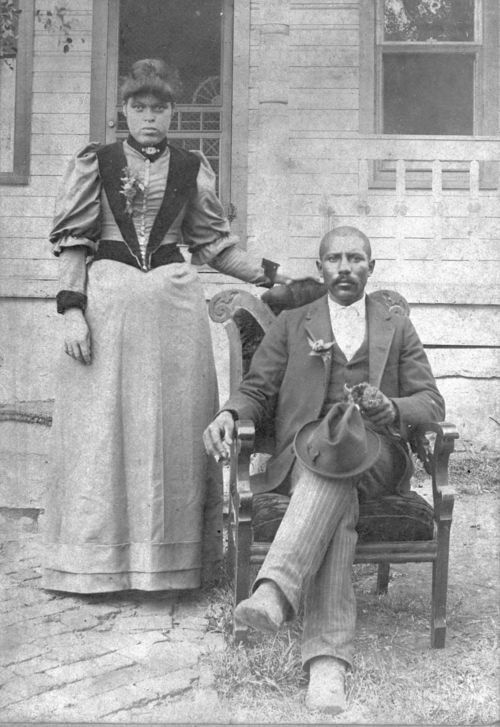

Above image credit: George and Sylvester “Pat” Johnson, Reuben Benton and Leroy Doty came to be known as “The Foursome.”In March 1950, four Black men placed their fees on the counter of the whites-only Swope Memorial Golf Course and left to tee off.

Slashed tires, broken windows and a decade-long battle to assert the right for equal play on Kansas City’s golf courses ensued.

Those four men, George and Sylvester “Pat” Johnson, Reuben Benton and Leroy Doty, came to be known as “The Foursome.” In 2014, their act of civil disobedience landed them all a spot in Kansas City’s Golf Hall of Fame.

This is one of many stories that will be explored in an upcoming documentary about the history of Black golfers by the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City and local production company Reel Images.

Reel Images is owned and operated by filmmakers and childhood friends Rodney Thompson and Stinson McClendon.

“To me, their pushback was monumental to the history of desegregation in Kansas City,” Thompson said. “It speaks to our tenacity as African Americans that we’re not taking no for an answer.”

Thompson also noted that the event of pushing back against racism in public spaces is bigger than Kansas City – it’s an American story.

The Foursome’s famous round of golf came four years before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. De jure segregation still ruled Kansas City, and the documentary will explore the impacts of that on the golf course both locally and nationwide.

Kansas City’s golf craze was in full swing in the 1920s. At the time, Black golfers played on a course near Edwardsville that farmer Junius George Groves (known as the “Potato King of the World”) carved out of his land.

Black Archives ombudsman and documentary co-producer James Watts kindly described the course as “rustic.”

From this golf course came the Heart of America Golf Club, an association for Black golfers.

Around the same time, the United Golfers Association was founded by a group of Black businessmen who wanted to open up the game to Black Americans. The UGA hosted golf tournaments in cities around the country, including Kansas City.

“A golf tournament was similar to an HBCU homecoming,” Watts said.

UGA tournaments tended to draw out huge names like boxer Joe Louis and jazz legend Count Basie, and were enjoyed by more than just men.

“When you get into the history, a lot of women got tired of their husbands being gone all the time and wanted to see what they were doing,” Watts said.

Despite the growing scene for Black golfers, records show that players were suffering from segregation in more ways than one.

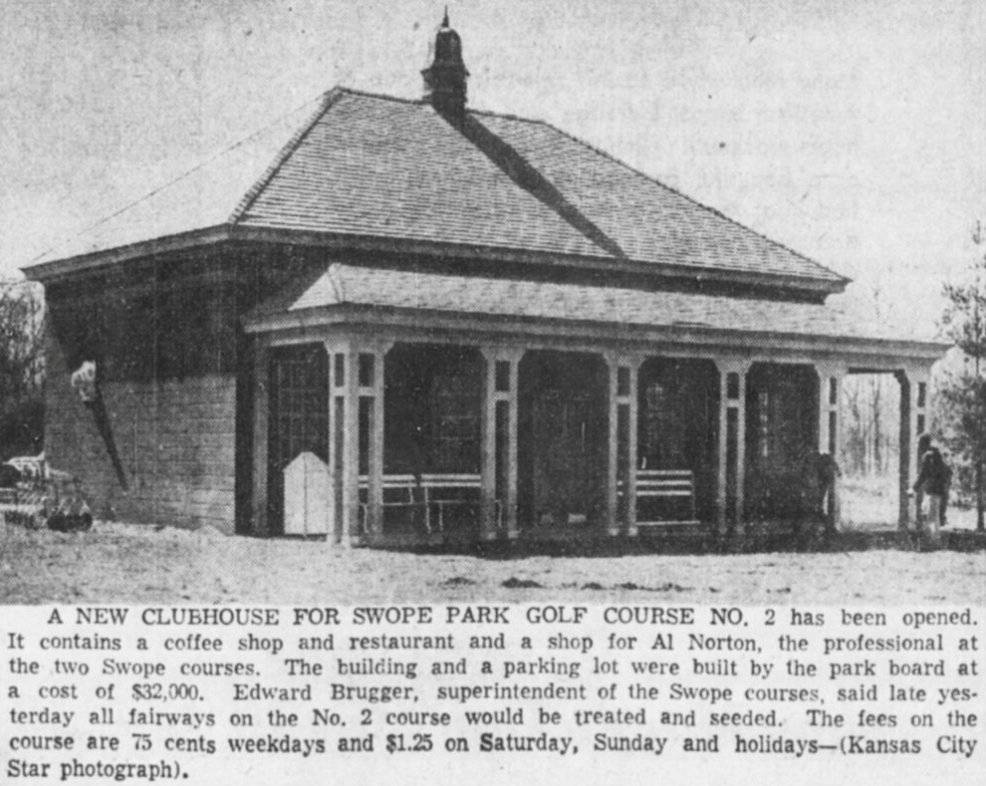

By the 1930s, some Black men were able to play on Swope Park’s lesser golf course, but only on Mondays and Tuesdays. In 1938, the Heart of America Golf Club sued the city for the right to play on golf courses that their taxes funded.

Records at that time also showed that Kansas City’s Black golfers were getting beat in local tournaments due to their lack of opportunities to practice on adequate courses.

Those that were good enough to do well in tournaments knew that their career could only get so far.

“I think it was very rewarding but painful,” Watts said. “The reward was winning, but the pain was knowing you could win a tour on the UGA but not play in the PGA”

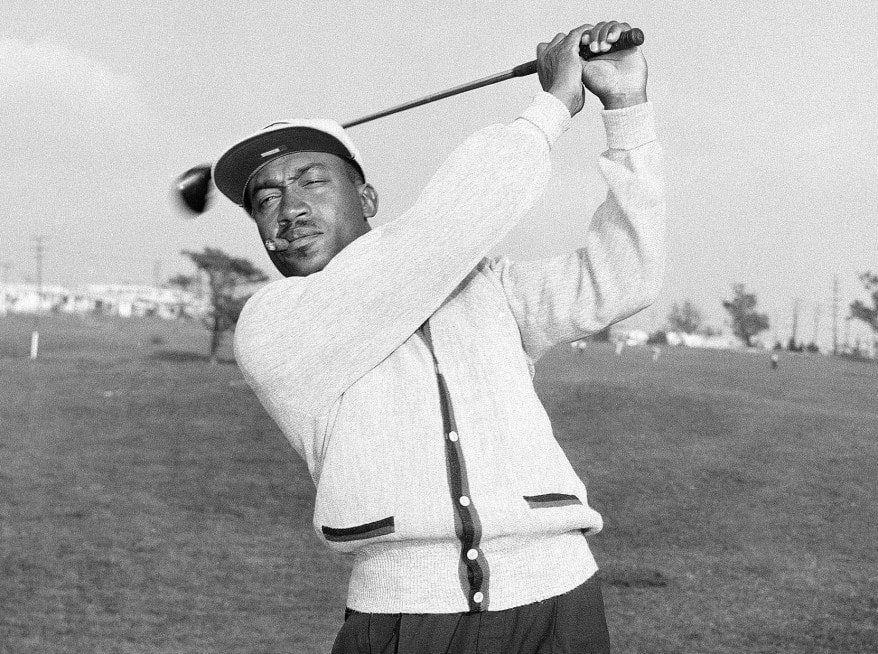

The Professional Golfers’ Association of America removed the “Caucasian-only” clause from their by-laws in 1961. Shortly after, Althea Gibson became the first African American woman to join the Ladies Professional Golf Association 1963. The following year, Pete Brown became the first African American to win an official PGA tour event.

Some folks hold on to the belief that integration or the rise of Tiger Woods signaled the end of racism in golf, but insiders know that that isn’t the case. According to Watts and many others, it’s still very difficult for Black people to break into golf.

“You need a sponsor,” he said. “It’s more than just being good.”

Exorbitant startup costs and lingering racism still make the sport challenging, but Thompson hopes that the film will inspire younger Black people to make a place for themselves.

“It’s relevant today for young people to build on the foundation that those people presented us with,” he said. “They showed us how to push back.”

A title for the film hasn’t been announced, but Watts is considering “The 19th Hole.”

“The 19th hole was the parking lot under a shaded tree with a beer because they weren’t allowed in the club,” Watts said.

Interviews for the documentary began recently, and the release date is to be determined.

Catherine Hoffman covers community affairs and culture for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.