The Cost of Churn: Evictions Hinder Classroom Progress for Kids

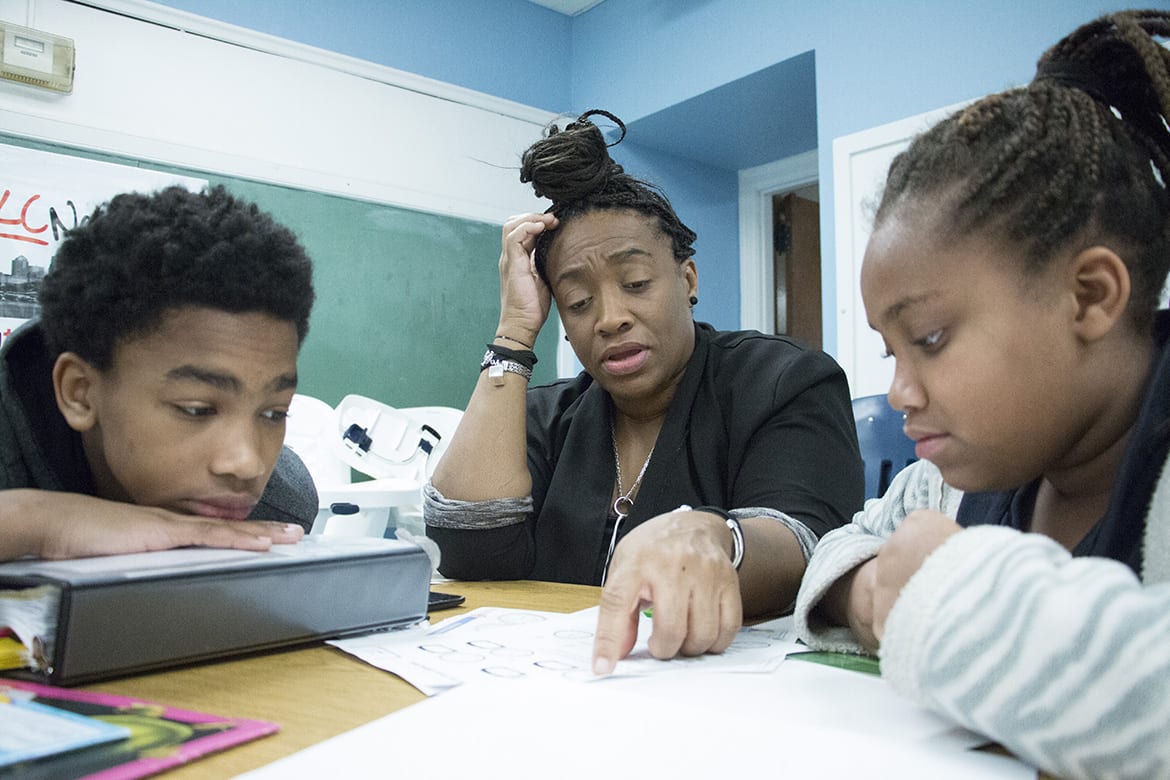

Tameko Davison helps her second-grade daughter, Baustyn Looney, with her homework on telling time in the dining room of City Union Mission's family center. Davison's son, Khiiro Azaire, looks on. (Mike Sherry | Flatland/Video: Emily Woodring and Cody Boston)

Tameko Davison helps her second-grade daughter, Baustyn Looney, with her homework on telling time in the dining room of City Union Mission's family center. Davison's son, Khiiro Azaire, looks on. (Mike Sherry | Flatland/Video: Emily Woodring and Cody Boston)

Published January 29th, 2018 at 1:49 PM

Tameko Davison’s children were well into the routine of a school year when turmoil intervened in the form of an eviction notice.

Davison fell behind on payments, and the gas was shut off to her government-subsidized apartment in Kansas City. That violated a Kansas City Housing Authority rule and caused her to lose her rent voucher. Her landlord went to court to have her removed.

“They gave me 10 days to get out,” Davison said. “I was just calling around to all of the shelters. Everywhere I called they had no bed or anywhere for me and my kids to go.”

Finally, a space opened up at the City Union Mission’s family shelter. After a month there, Davison said she was receiving invaluable counseling and life skills training, and was more optimistic about her prospects. But the displacement disrupted her children’s school life.

Both her daughter, Baustyn, a second-grader; and son, Khiiro, in seventh grade, missed two weeks of classes because of the eviction and move. They returned to the Kansas City schools they’d been attending since August. But their new, temporary address means longer rides to and from school and more uncertainty in young lives that have never been predictable. Davison is contemplating transferring both students to other buildings.

If that happens, Baustyn and Khiiro would join a tribe of school-age nomads throughout the metropolitan area.

“The day we got back from winter break I had five phone calls from people who were getting evicted,” — Heather Schoonover, community liaison, Olathe Public Schools.

Students change schools because their parents lose jobs or find jobs. Or someone in the household is on the run from an abusive partner, a landlord or bill collectors. They move because a new management company took over their home and raised the rent. Or the basement flooded, or the furnace doesn’t work. Sometimes they move because they’ve found a better place.

Whatever the reasons, frequent moves in and out of classrooms are becoming a leading concern of educators in the Kansas City area. And conversations about student mobility — or churn, as it is often called — frequently overlap with the broadening discussion about the Kansas City area’s unstable rental market and high rate of evictions.

“It’s staggering to me to think of how many formalized evictions there are and how many more are not formalized,” said Nicole Sequeira, family services coordinator at the Independence School District.

Sequeira was referencing numbers from an academic study that has caught the eye of educators and others. Tara Raghuveer, a Shawnee Mission East High School graduate who attended Harvard University, studied evictions in the Kansas City region for a university thesis. Through that research and subsequent work, she found that landlords in Jackson County filed an average of 42 eviction petitions on every business day in the period from 1999 to 2016. In 2016, judges handed down 25 eviction decrees per business day.

The numbers add up to dozens of households — many with children — set adrift every week in Jackson County, and more in Wyandotte, Clay, Platte and even Johnson County.

“The day we got back from winter break I had five phone calls from people who were getting evicted,” said Heather Schoonover, community liaison for the Olathe Public Schools.

As workers in schools and shelters know only too well, an eviction is an express ramp to homelessness. It is an ugly splotch on a renter’s record that causes would-be landlords and property owners to disconnect phone calls and slam doors.

“Right now I have nine families, and seven are here because of evictions,” Cathy Asher, manager of the Salvation Army’s Crossroads Shelter in Independence, said one day in December.

Unable to rent decent housing, evicted families cycle in and out of shelters and homes of relatives. Some end up renting hotel rooms for weeks on end, or sleeping in vehicles or abandoned houses.

“I believe it delays (the students), because they are constantly starting over.” — Melissa Douglas, office of students in transition, Kansas City Public Schools.

Suyin Diemer, who was staying at the City Union Mission in December, blamed an eviction several years ago for launching her family into a cycle of transience and rental horrors.

“With an eviction, you’re high-risk, and there’s nothing suitable for you and your kids that you can really get,” she said. “I have to just deal with the landlords who will have me, the slumlord types.”

The last house she lived in had sewage drainage in the basement and no furnace, Diemer said. “When I brought these things to (the landlord’s) attention, that’s when he came down on me and asked us to leave. He didn’t go as far as an eviction, but he had the utilities shut off. I found places for my daughters to stay, and I stayed for almost two weeks in that cold house.”

Two of Diemer’s four daughters were with her in the shelter. One was with a sister, and another was staying with a friend. Diemer figures her family has moved five or six times in as many years, and she’s lost track of all the schools her children have attended.

“It affects them really bad,” she said. “We had to do those moves, and we ended up in places like this, you know, shelters and stuff. My daughters were rebelling against me because they have to be here. Our living situation has a terrible impact on their schooling.”

Research

That is the case universally. Research has found that frequent moves, especially traumatic ones like Diemer and her daughters have endured, cause students to miss school, fall behind their classmates academically and be less likely to graduate.

A study completed a few years ago by the Kansas City Area Education Research Consortium found that 1 in 5 students on the Missouri side of the Kansas City metropolitan area moved at least once during the 2015 school year. Those students in general had poorer attendance and lower test scores than their peers who stayed put. Prospects were even worse for the more than 6,000 children in the study who moved two or more times while classes were in session.

A recent analysis of second-graders in Kansas City Public Schools showed that students who had attended the same school since kindergarten had a better chance of meeting grade-level proficiency measures in reading and math than students who had switched schools.

Studies from elsewhere suggest that students lose three months of academic growth in math and reading with every transfer during the school year, and students who move three or four times before sixth grade may be a full year behind their peers academically.

Melissa Douglas, who runs the office of students in transition for Kansas City Public Schools, sees the toll that housing instability and frequent school transfers exact on children.

“I believe it delays them, because they are constantly starting over,” Douglas said. “It puts them at a disadvantage academically. We also see a lot of discipline problems that come with that.”

Classroom churn is hard on others besides the kids who move. Teachers throughout the metro area tell stories of children who simply disappear from classrooms, leaving their school supplies behind and their friends to wonder what became of them. On the flip side, frequent arrivals of new students during the school year consume teachers’ time and interrupt classroom dynamics.

Schools aren’t required to keep data on the role of evictions in creating student churn. But informal record-keeping indicates it is significant.

Douglas, whose office has worked with more than 800 students so far this school year, says her staff estimates that evictions are a factor in almost a third of their caseload.

In the Independence School District, surveys indicate that about 1 in 5 families who seek services available to homeless students have been evicted, Sequeira said.

Leslie Washington, student services specialist for the Hickman Mills School District in south Kansas City, said more than 300 students had qualified for services so far this school year under a federal law requiring schools to assist homeless or transient children. Of that number, at least 35 students had been affected by evictions.

A federal law, the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, seeks to guarantee educational access and stability for children who qualify as homeless. Though largely an unfunded mandate for school districts, it helps some families avoid moves. In most cases, districts provide transportation from shelters or temporary housing arrangements so that students can remain in the same school through the academic year.

But creating new bus routes or funding cab rides for uprooted students is an expensive remedy, and one that often still requires students to transfer to different schools at the start of a new school year.

Prevention

Around the area, some school districts are joining forces with social service and community groups to try to keep families from becoming homeless in the first place.

The Shawnee Mission School District, which works with about 425 homeless students a year, has enlisted churches and other community partners to raise money for back rent and overdue utility bills. So far this school year the partnerships have kept 20 families from becoming homeless, said David Aramovich, the district’s McKinney-Vento social worker.

One of those families was Dawn Myers and her three children, two of whom are students in the district. Myers said she got into a jam due to a disruption in the child support payments she receives. Though her rental history was good up until then, the manager of the house she was renting evicted her.

That launched Myers, who works at Catholic Charities, into the same fix as many of the agency’s clients. Even though she had gotten her child support situation straightened out and started working a second job, no one would rent to her.

“If you have anything other than a stellar record you’re not going to find housing in Johnson County,” she said.

With few options, Myers and her children moved into an extended-stay hotel for six weeks. She was surprised to learn how many other guests were renting rooms because of housing difficulties.

It was Myers’ son, a high school student, who approached Aramovich. “He was on it right away,” Myers said.

The school district partnership helped pay a portion of the hotel bill, adopted the family for Christmas and made sure they had food and household essentials. Aramovich was researching housing options for Myers when her family found a two-bedroom apartment. She pays $1,200 a month in rent.

“You think you understand challenges, but when you’re in a situation there’s so much more to it,” Myers said.

Aramovich said Shawnee Mission schools are seeing the effects of a rental housing market that is becoming prohibitively expensive for lower-income families. Johnson County has few homeless shelters, so most displaced families move in with relatives and friends — a circumstance known as “doubling up.”

“It’s getting less likely that you’ll find second-chance landlords,” agreed Valorie Carson, community planning director of United Community Services of Johnson County. “Households who have one eviction notice will find it hard to re-establish housing in Johnson County.”

The Johnson County Sheriff’s Department handled about 2,100 evictions in 2017, records show.

“If we can stop an eviction from happening, the kids will never have to move.” — Bruce Bailey, a vice president, Community Services League, Independence, Missouri

Olathe Public Schools also works with an extensive network of faith and social service groups, alumni, retired employees and others.

“A lot of my time is spent keeping people out of the McKinney-Vento program,” Schoonover said.

But that isn’t always possible. Olathe Public Schools worked with 413 homeless or transient students in the 2016-17 school year and is already up to 320 this school year. Of that number, almost 80 percent are temporarily doubled up with family and friends.

“They’re couch surfing,” Schoonover said. “A family might live in one room in a basement because they got evicted and they have no place else to go. There’s not enough shelters and not enough affordable housing.”

The links between housing instability, evictions, student mobility and academic performance seem obvious, but it’s taken a long time to connect them in the local conversation. This year marked the first time that a Kansas City Public Schools superintendent cited moves in and out of classrooms during the school year as a factor in a disappointing accreditation report.

People who work directly with struggling families see the connection clearly.

“Our first priority is to keep kids in school. That’s usually done by keeping mom and dad in their home,” said Bruce Bailey, a vice president at the Community Services League in Independence.

Bailey and his agency participate in the Family Stability Initiative, a national effort funded by the Siemer Institute for Family Stability in Columbus, Ohio. With funding channeled through the United Way of Greater Kansas City, the Community Services League and Metropolitan Lutheran Ministries provide extensive counseling and support for at-risk families with the aim of preventing school moves.

“If we can stop an eviction from happening, the kids will never have to move,” Bailey said.

He and others at his agency work with 30 to 40 families at a time. They might help with overdue rent or utility bills, but their goal is to arm parents with the knowledge and tools to avoid the kinds of jams that lead to eviction.

“Keeping kids stable and enrolled in school so they can advance academically is going to make a huge difference in their lives and their chances of escaping generational poverty,” said Lynn Rose, senior vice president at the Community Services League.

But the resources available to help at-risk families remain in their homes are a drop in a very large bucket. Keeping more children in classrooms will require the kind of broad-lens look at policies around evictions and affordable housing that is only now getting started.

Ongoing Problem

Meanwhile, the dislocation continues.

Terry Megli, family ministries director at the City Union Mission, said at least half of the parents who come with their children to the emergency shelter have evictions, either as the cause of their immediate dislocation or in their past. The staff can sometimes persuade a landlord to accept a partial payment to erase an evictions judgment, Megli said. But often the hole is too deep to escape.

That 50 percent includes Davison, who laments that her children have changed schools frequently. Baustyn, the second-grader, is at her third school already.

Davison herself had a transient childhood. Her father drove trucks, and the family moved around the country. “I loved to travel, but I didn’t like the instability,” Davison said. “I wanted the kind of life where I had a house and a good friend in the neighborhood. I didn’t have that. It left me kind of lost.”

Though she hasn’t benefited from a stable life, Davison has a picture of what one looks like. It revolves around a house, a family and a school. “I would like to give my kids that,” she said. “But so far it hasn’t worked out.”

—Barbara Shelly is a veteran journalist and writer based in Kansas City. Follow Flatland @FlatlandKC.

Kansas City PBS and its digital magazine, Flatland, are gathering in-depth reporting and engagement around affordable housing in the metro, including this story on how evictions affect education. Watch for resources, ways to get involved, and more reporting at our project main page,

Kansas City PBS and its digital magazine, Flatland, are gathering in-depth reporting and engagement around affordable housing in the metro, including this story on how evictions affect education. Watch for resources, ways to get involved, and more reporting at our project main page,