After Blowout Loss, How Can Stadium Issue Be Revisited? History Shows You Win Some, You Lose Some When it Comes to Stadium Proposals

Published April 11th, 2024 at 6:00 AM

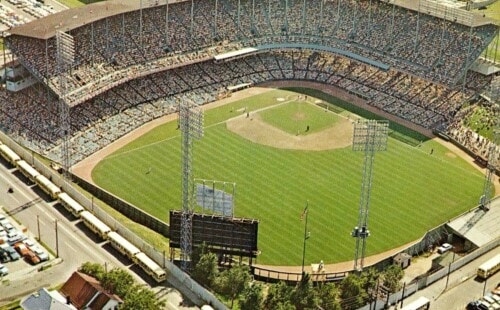

Above image credit: An aerial view of Truman Sports Complex, home of the Kansas City Royals and Kansas City Chiefs. (G. Newman Lowrance | via Associated Press)In football terms, it was at least a three-possession margin of defeat.

In baseball terms, it was like that moment when a utility infielder took the mound for the team losing 15-0 in the seventh inning.

In Kansas City area political terms, the April 2 voter rejection of the Jackson County stadium sales tax was a wince-worthy, the-voters-have-spoken defeat. The proposal failed overwhelmingly, with 58% opposed compared to 42% in favor.

The result, plus a growing skepticism nationwide for referendums authorizing public financing of stadiums used by privately owned sports franchises, makes it easy to wonder if last week’s election was a political game changer.

At least some veterans of similar Kansas City area stadium campaigns aren’t buying it.

“I don’t think see this as, ‘Oh my gosh, we are never going to be able to approve a vote ever again,’” said former Jackson County Executive Katheryn Shields, who in 2006 helped lead the successful campaign to authorize a three-eighths cent sales tax to renovate Kauffman and Arrowhead stadiums.

“I don’t think this in any way shows that the citizens of Jackson County are less willing to support their sports teams than they have been.”

The result does show, Shields added, that any similar ballot measure proposed in the future needs to be more clearly communicated to voters.

“It is just a statement that we need to take the time to have everything crystal clear so that the public can understand it and then say, ‘Yes, we want to support this.’”

In 2004, Ed Eilert, former Johnson County Board of Commissioners chair, served on the committee championing Bistate II, an attempt to replay the success of the original Bistate campaign that saved Union Station.

Bistate II would have established a quarter-cent sales tax to pay for $1.2 billion in Truman Sports Complex upgrades as well as arts programs in several Missouri and Kansas counties. The Chiefs and Royals each would have received $180 million in tax revenues to upgrade their stadiums at the Truman Sports Complex.

Voter approval was needed in Jackson and Clay counties in Missouri plus Johnson County in Kansas for the tax to take effect.

While voters in Jackson County approved the proposal, voters in Johnson and Clay counties rejected it, as well as voters in Platte and Wyandotte counties.

The measure failed, Eilert said this week, not necessarily because of any emerging national mistrust about the earmarking of taxpayer dollars for major league sports franchises.

It failed, he said, because of a specifically local issue.

The ballot measure, Eilert said, had included the provision that every county approving it would receive a seat of the Jackson County Sports Authority, the nonprofit entity that oversees the Truman Sports Complex.

The Missouri General Assembly established the authority in 1965.

“But for whatever reason the Missouri legislature refused to make the alteration in the membership of the sports authority, and that kind of killed it,” Eilert said.

Those opposed to the proposition made hay with that, Eilert added.

“Taxation without representation was a pretty easy sell.”

Pile of Rubble

Kansas City area voters have a long history of supporting stadium referendums that include public financing, going back to separate proposals in 1931, 1954 and 1967.

“For almost three generations voters have recognized the need in small markets like Kansas City to have public financing for stadiums,” said Jack Craft, a Kansas City lawyer who in 2004 served as chair of the Think Big Committee, the campaign backing Bistate II.

Over the past 20 years, if voter sentiment for the public financing for privately held sports franchises in the Kansas City area was charted like a publicly traded stock, it would resemble a buy-and-hold security, despite occasional volatility.

- In August 2004, Kansas City voters approved a ballot measure increasing hotel fees by up to $1.50 a day, and rental car fees by up to $4 per day, to help pay for a new downtown arena.

The proposal was different from the April 2 vote, which proposed extending an existing sales tax across Jackson County.

Also, there were no major league sports franchises listed as likely arena tenants – even though proponents believed the facility, when built, might attract one.

Voters approved the fees by a 57% to 43% margin. The T-Mobile Center (then Sprint Center) opened in 2007 and has operated as a concert venue and collegiate sports showcase – although there are still no major league teams in residence there.

- That November voters across several Kansas City area counties rejected the Bistate II proposal.

- But in 2006 Jackson County voters, while declining to approve a rolling roof at the sports complex, did approve a three-eighths cent sales tax designed to fund $450 million in upgrades for the stadiums. The Chiefs pledged an additional $100 million while the Royals offered $25 million. Voters approved that by almost 54% compared to about 46% against.

- Then, last week, Jackson County voters soundly rejected a continuation of that same tax beyond 2031.

Despite last week’s events, Shields still thinks a Jackson County stadium ballot measure could be viable.

“Given the right plan, the tax could be successful,” she said.

Shields recalled that Royals owner John Sherman asked for a meeting with her last year. Sherman, she added, “showed me a video and asked if I had any questions.”

She had two main concerns, the first of which concerned parking, or the lack of it.

“I said, ‘You don’t seem to be building any parking,’” Shields said. Sherman’s answer, she said, referenced the approximately 40,000 parking spaces often cited by proponents.

“And while that may be true, I think a lot of people had trouble envisioning that,” Shields said. “So that was a big open question.

“But the more basic question was ‘How would you pay for it?’”

Before the election, the Royals estimated the new stadium would cost about $1 billion to build, with the sales tax extension generating about $350 million of that.

That left a deficit, Shields said, of at least $650 million or perhaps more. Where, Shields said she asked, would that money come from?

“That was a question that never got addressed in any way,” she said. “And I think that was a huge question in the minds of the voters.”

That was, she said, in contrast to the detailed financials that were made available to the public during the 2006 county sales tax campaign.

“In 2006 we had fully negotiated leases that said that, if there were to be cost overruns, the team would cover those.

“We had a very clear program that the voters could look at and make a decision on. And that just wasn’t here in this election.”

Although members of the Jackson County Legislature also asked to meet with her last year, she had no official role in the campaign, Shields said.

Nor did Eilert, who said he wondered why sales tax proponents seemed to show far more haste in placing the proposal on the April ballot than they did in providing specific details to voters.

“I understand the benefits of having a downtown stadium,” he said. “If you look around at those Major League Baseball communities that have downtown stadiums, there is a lot of economic benefit to be gained.

“But in this particular case I wondered why they had to move so quickly to a vote where there were so many issues that were left unanswered. This should have been more clearly defined, with alternatives presented to those whose businesses would have been impacted.

“I don’t know whether that happened or not.”

Eilert also was uncomfortable, he said, with a post-election scenario that could leave at least one iconic Kansas City property without a tenant.

“How do you walk away from the significant public investment that has been made in Kauffman Stadium and in Arrowhead – and then turn Kauffman into a pile of rubble?”

Craft, meanwhile, believes a future proposal could find voter support if it was rolled out in a more orderly fashion.

“My impression is that the rejection had more to do with the process than it did with the idea,” said Craft, who also was not involved in the sales tax campaign.

“I have always thought the voters needed to know what they were voting for and, in this case, there were way too many ambiguities regarding the costs and the revenues.

“Voters didn’t have enough information.”

It’s Not Over

It’s not just Kansas City grappling with stadium financing. Across the country, the record of stadium ballot initiatives is rather mixed.

“There is a growing skepticism about public subsidies for stadiums,” said Timothy Kellison, associate professor of sport management at Florida State University.

While each case has its own specific context, Kellison added, last week’s Jackson County sales tax vote was notable in one specific way.

“There was this very well-mobilized opposition group that was really important in defeating the subsidy,” he said.

“Certainly, in other cities there has been opposition, with certain groups trying to unify. But this was one of those cases where a well-organized group was already in place.”

Over the past 40 years, voters have approved 60% of almost 50 propositions or referendums that have involved public funding, or a property rezoning requests for a major league sports facility, according to a recent study in Street & Smith’s Sports Business Journal.

But while many proposals have met defeat initially, teams often have secured public financing later.

“Generally, a defeat at the polls does not mean a team, or teams, will not end up getting public money in the long run.” Kellison said.

One option has been to avoid a public vote.

According to research conducted by Kellison and fellow scholars, most stadium projects across North America have received public financing without any citizen vote.

For example, two stadiums in the Kansas City area recently have been built without formal ballot referendums.

What is now Children’s Mercy Park, home to Sporting Kansas City of Major League Soccer, opened in 2011.

The stadium was part of a development deal that secured the construction of two office towers built by Cerner Corp., the health care technology firm, in western Wyandotte County. State and local officials agreed on a subsidy package that included $85 million in state tax credits and approximately $114 million in bonds.

Moreover, CPKC Stadium, the approximately $120 million home of the National Women’s Soccer League’s Kansas City Current, which opened last month at the east end of Berkley Riverfront Park, was almost entirely privately funded.

And yet the awarding of public subsidies without a vote can generate its own pushback among voters.

“A public vote at the ballot box is not always a panacea,” Kellison said.

“But certainly, it does resemble what most Americans think is a democratic process. And in cases where large amounts of public money are spent without the direct consent of the public, that could generate questions about local governments and the decision-making process.”

Meanwhile, in Kansas City, Kellison believes, it’s not over until it’s over.

“The outcome of the vote should inform policymakers and team ownership and give them a good sense of how the public feels about subsidies and should take them back to the drawing board to think about other ways of getting what they want.

“It will be interesting to see what the next move is from the Chiefs and the Royals.”

Surviving the Comments Section

One strategy might involve finding a way to neutralize the “billionaire” charge.

Some opposed to the downtown stadium proposal made frequent use of the pejorative, apparently to invoke the idea of an oblivious sports franchise owner threatening to bigfoot an arts and entertainment district developed over decades by individual risk-taking entrepreneurs.

The word often appeared in social media posts, sometimes prompting charged language.

“(Blank) the Kansas City Royals for life!” read one post.

“Beside your middle finger, anything valuable to show the world?” read a reply.

Craft shrugged off any larger social media impact on the election, saying the sales tax extension proposal’s lack of clarity sank it.

“It also mattered that there was some division at the county level – that contributed to it,” he added, in reference to Jackson County Executive Frank White’s opposition to the recent sales tax proposal.

Meanwhile, both Shields and Eilert believe future stadium proposals, if presented to voters in a transparent manner, and then vetted in good faith, could survive the comments section.

“Social media is always a hotbed of whatever,” Eilert said.

In the 2004 Bistate II campaign, it was the Missouri legislature’s refusal to authorize representation for the approving counties that halted momentum, he said.

The successful 2006 sales tax vote, meanwhile, prevailed despite the snark. After proponents adopted the catch phrase “Save Our Stadiums,” some opponents designed a mocking website accessed at “saveourowners.com.”

Derision is not a recent feature of hotly contested ballot measures, Shields said.

“This is nothing new,” she said, adding that the rhetoric of some opponents “often is merely grounded in insults and innuendo.

“I do think – and we are seeing this at all levels of government – the ability of any individual to spontaneously express anything and instantaneously send it out to the world has certainly lowered the quality of discourse.”

Beneath the noise, she added, legitimate issues with the sales tax extension were what mattered, and they were not addressed sufficiently.

“I do think the Royals, if they continue to believe they need a new downtown baseball stadium, need to make the case as to why, as opposed to making upgrades where they are.

“And to somehow pretend that Royals’ stadium is falling down while the Chiefs’ stadium is not?

“That doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016.

The problem was bullying and blackmail by the owners and top management. They need to find a good spokesman that talks to the people. And then keep their mouths shut. It may be the way to talk in big business but to people trying to pay for the necessities in life.

Just a few months before this vote Jackson County had slammed residents with horrendous increases in property tax. People are still losing their homes or facing dire cuts in medication and other essentials to stay in their homes. Rents are way up. Businesses have had to raise prices to cover the taxes. And then about the same time as the stadiums vote, the mortgage company sent me the bad news — my monthly payment went up 30% thanks to Jackson County. And then they ask us to stick ourselves with a sales tax increase (yes, 40 years is an increase). Maybe voting no was the only way to immediately get back at the Jackson County incompetent or conniving officials who screwed the citizenry. Every month we will be reminded what they did.