In ‘Service,’ A Celebrated Photographer Turns His Lens On U.S. Troops

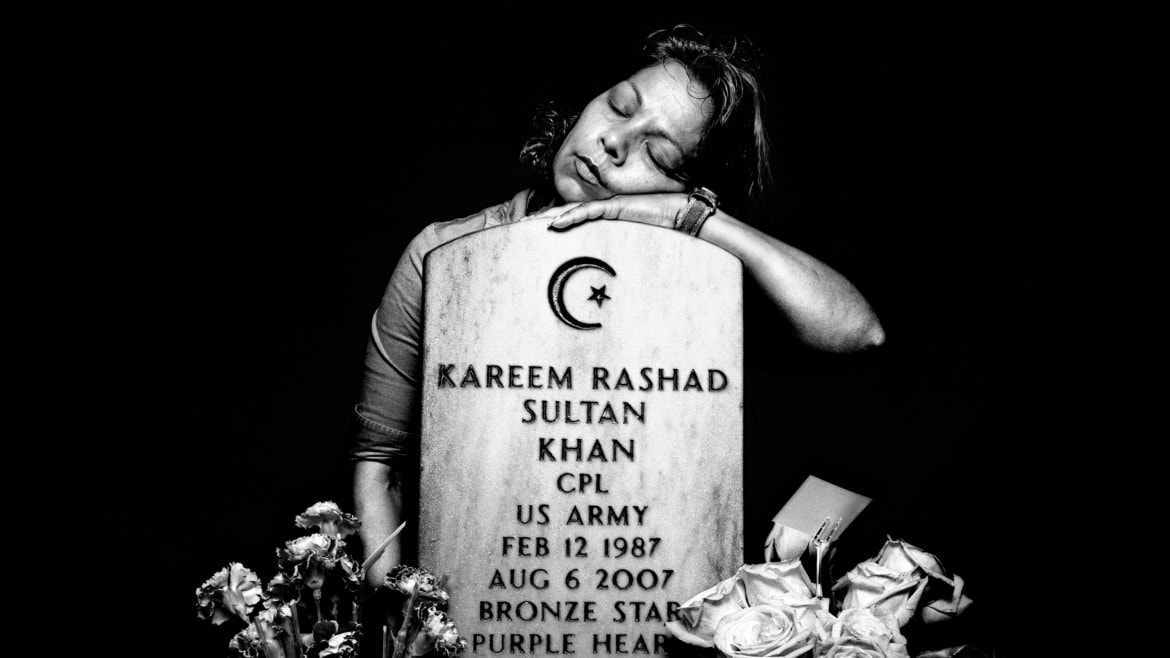

Elsheba Khan at the grave of her son, Spc. Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan, in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery, 2008. Spurred by the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, Khan, a Muslim, enlisted immediately after graduating from high school in 2005 and was sent to Iraq in July 2006. He was killed a year later.

Elsheba Khan at the grave of her son, Spc. Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan, in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery, 2008. Spurred by the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, Khan, a Muslim, enlisted immediately after graduating from high school in 2005 and was sent to Iraq in July 2006. He was killed a year later.

Published May 30th, 2016 at 9:54 PM

As a celebrated portrait photographer, Platon Antoniou (who goes professionally by his first name) is well-known for his close-up depictions of the powerful. He has aimed his camera at the faces of celebrities and world leaders ranging from Vladimir Putin and Moammar Gadhafi to Willie Nelson and Woody Allen.

“Sometimes,” he says, “you look in their eyes and you see angels. And sometimes you see demons.”

Platon’s 2011 book, Power, featured photos of more than 100 world leaders. In Service (Prestel Publishing), the British-born photographer turns his lens on U.S. military personnel and their loved ones.

“I have a rather strange perspective on the times we’re living in,” he says, “because I’ve had very intimate moments with heads of state, and yet I’ve also had these very powerful moments with the people who have to play out the policies that our leaders put forward. It leaves me as someone in the middle.”

The book results from a project that began back in 2008, an assignment Platon took on after he was appointed as Richard Avedon’s successor as staff photographer at the New Yorker. (He now dedicates much of his time to The People’s Portfolio, a nonprofit organization he founded to highlight underreported stories around the world.)

First, he spent time with troops while they trained in a simulated Iraqi village at the U.S. Army’s National Training Center at Fort Irwin in the Mojave Desert, before they were deployed. Then he waited for them to return. When it was possible, he photographed them again — or the loved ones who survived them.

“I had done so many portraits of leaders,” he says. “And what is great leadership? We have seen it being about confidence, charisma, strength, decision-making. We all know that side. But there’s another side that’s far more complicated — that’s the idea of service. I wanted to find out what happens when you’re asked to do something and you do it — and it’s very dangerous, and the sacrifices you make. This is where I learned about the other side of leadership, which is service.”

In the waning weeks of the 2008 presidential campaign, the New Yorker published several of Platon’s images. One, showing a grieving mother at Arlington Cemetery embracing the headstone of her son — a Muslim-American soldier killed in Iraq — caught the eye of former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who highlighted it as he announced his endorsement of Barack Obama, who he hoped would be a unifying figure as U.S. president.

“The picture of the mother is the big question of our time: What is it to be American, to be patriotic, to give good service?” Platon says. “Unfortunately, the reason why the [image of the] mother was so powerful — that terrain is even more heightened now. I’m left with this sadness. Did we learn nothing?”

What did you first set out to do in this project?

Platon’s ‘Service’.

We had an election coming, as we do now. We had this idea: How do we do a large-scale photo essay that provokes and stimulates respectful debate? I was interested in looking at poverty in America, but other issues came up and the U.S. military was one of them.

We focused on America’s role militarily, and slowly, it morphed into this idea of service — it became less about war and was more about the human story behind the war. We wanted to avoid politics. We had this idea not to photograph anyone famous. This is really about ordinary men and women and families who all give great service. It was certainly an emotional roller coaster and it pushed me so far.

Describe the training camp you spent time in.

It’s 100 square miles in California, in the desert, where they built Iraq. [The simulated Iraqi village] was called Medina Wasl. The soldiers called it “The Suck.” They were sent there for the last two weeks before deployment to really get their heads in the zone. There’s tanks tipped over on fire. All the signs are in Arabic. They had a Humvee which was exploded five times a day on routine patrols with IED explosives. It was more and more disfigured as the demonstrations continued.

You feel like you’re in Iraq; it’s 105 degrees. [The soldiers] are ambushed by role-playing terrorists; people are screaming. They use amputee role players coming out screaming, holding part of their foot.

I was allowed to photograph all this. I built a small studio and invited [people] in.

They called this street [at the camp] “Trauma Lane,” and that was the working title of the book for a long time. As the project shifted to the return home, I realized there was something more than just trauma here. There was tenderness, feelings, love and compassion. So it shifted to something more universal, which became Service.

The conditions sound challenging, not your usual studio photography.

It was a godforsaken place. I’ve never been to war; I’ve never experienced anything like that. I was suddenly put in this hellhole of a place, and that wasn’t even the real thing. It felt a bit like Apocalypse Now. Things start to get a bit warped. The Hasselblad, the camera I use, has this leather on the side glued onto the metal, and it was so hot, the glue was melting. All the casing started to come off.

We worked 15-hour days in the heat for four or five days. There was nowhere to shower. At night, you could hear explosions going off, but after awhile you’d fall asleep because you were exhausted.

You had a rude awakening one night, right?

I remember I felt this pressure between my eyes, and I woke up and there was a gun — I don’t know what kind of gun because I’m not a gun kind of guy — but it was one of these machine gun things pointing right between my eyes, with night vision. The guy looked like some version of Robocop — I nearly had a heart attack. He just whispers as he presses the barrel more and more into my flesh, “Don’t. Move.”

It was a [simulated] nighttime patrol mission. I just lay there. He steps over me and just carries on walking. I wanted to say, “But I’m a New Yorker photographer! I’m just here doing portraits!” But obviously you daren’t speak.

I actually found the guy who did it the next day. I wanted to show everyone what it felt like — “Would you help me do that?” He said sure. And he points the gun right at the camera. It’s not the same, because [originally] it was nighttime and I was half-asleep. But the feeling of that giant looming over you with perspective, the gun literally coming into your face, was the nearest I could get to it as a portrait photographer.

You met some of the soldiers when they returned.

Yes, they were deployed. Then they come back and it’s all different. I waited with the families. I waited with this young lady [Beth Pisarsky]. The Humvee pulls up, [Airman 1st Class Christopher Wilson] steps out, and when these guys come back, they are built like rock — not just physically, but emotionally.

[Pisarsky] charged at him like a team of wild horses and almost knocked him over. And it was almost like an attack of love. I remember having to tilt the camera because I wasn’t expecting it, it surprised me. It was the beginning of emotion — now I’m not just seeing a sense of bravado, I’m now seeing what did it take to be a good servant. What price did you have to pay? You know he’s come back different.

There’s another shot of a soldier hugging [a loved one] and there’s a tear rolling down his face that isn’t just happiness. It’s complicated. And from now on, it’s going to be really complicated. He’s seen things you can’t unsee. And she hasn’t. But she’s experienced that they had a relationship that’s now going to be fundamentally changed.

So it became really human. It stopped being about the military and war, and turned into this human story that I never really expected it to be. I ended up taking pictures of love in the second half of the book.

Tell me about the portraits you shot at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

I did a portrait of [Jacquelyne Kay] with her arms around [husband Sgt. Tim Johannsen] in a wheelchair. And it became what I saw as this transference of power. She’s his wife and saying, “I’ve got him home now, no one is going to hurt him anymore.” The picture is divided into two halves. I remember thinking consciously, do I show his legs cut off? Maybe I should be more sanitized about it. Then I thought, no. You have to acknowledge both — the love and tenderness, and the brutality, danger, pain and trauma that’s also there.

He closed his eyes in her embrace. It was the most powerful thing. For him to show a sense of vulnerability, it made him all the more tough for me.

You also photographed people grieving in Arlington Cemetery.

I was photographing many bereaved families I had appointments with. And I was dreading that day. I was worn down. I also read the weather reports and they said in D.C., there were going to be terrible thunderstorms and wind and rain. I use strobe lights, it’s a whole operation, and on top of that, I’m dealing with the most acute sensitivities you can imagine. I am literally treading on sacred ground here. I was really nervous.

As the rain faded away, I noticed at the far corner of the cemetery a woman I didn’t have an appointment with. She brings a foldout picnic chair and would sit and read [at her son’s grave] every day. It was such a powerful and tender thing to witness. The dialogue between mother and son continues even after his passing. I went over and asked permission to take her picture.

She puts the book at the bottom of the headstone and goes behind it and cuddles the headstone as if she is cuddling her son. And then she closed her eyes. I was standing on the wet ground, where her son is buried, and I was so aware of the delicacies of my body language, and I was really looking at her face and hands and her mannerisms. I had no extra attention left over to notice that the book was the Quran or that the name on the headstone was a Muslim name. I thanked her and asked her name and she said, “Elsheba Khan.” I still didn’t think.

I took the pictures back to the magazine. When we were doing the edits, it was [New Yorker Editor] David Remnick who said, “Look at that.” We thought, “Oh my goodness.” We ran it in the photo essay with all the other pictures [in September 2008].

And shortly thereafter, that photo came up when former Secretary of State Colin Powell endorsed Obama for president on Meet the Press. He warned against divisiveness and said, “I feel strongly about this particular point because of a picture I saw in a magazine.”

He went on to describe exactly my picture. I’m sitting there with my mouth open.

That picture was described as a game changer, but it was not [a photo] of anyone powerful. I had worked with all the power players. But it wasn’t any of those that shifted people’s hearts and minds. It was an ordinary person, dealing with the one thing we have in common — we all love and lose. We’re all united by that. I received a letter from [Powell] that said, thank you for showing me in a very painful way what America really is all about.

Unlike the celebrities and power players you’ve photographed, here you were dealing with people often in a state of vulnerability. How did you establish trust with them?

It’s the difficult question — how do you do that? I wish I had a gimmick; I wish I had a trick. Trust means you have to be courageous first, with all your emotions open and so respectful and humble that there’s no room for your ego in this space. I am your servant and I am here to tell the world what happened to you. I can’t do it alone. I need you to be courageous with me. And if you really mean it, if you’re 100 percent committed, you can’t bulls*** that. You can’t fake it. It’s called authenticity.

And of course, that’s very traumatic. It’s very traumatic for me. Before a shoot, I don’t have a storyboard. I don’t know whether this person will be angry at the world — or maybe at me — or if they will break, how to deal with vulnerability. You have to be ready for the whole human condition to play out. You go in so raw. You just have to make very quick emotional decisions.

And sometimes I get it wrong.

How so?

I went to a lady’s house. Her name is Jessica [Gray]. Her husband wrote an op-ed criticizing America’s policy. Shortly after that, he was killed in Iraq. They’d recently had a little girl.

I’m setting up my studio in her living room. I’m dealing with a woman’s pain and courage, facing a new life that’s going to be difficult. That becomes consuming. I saw the flag they’d draped over his coffin and I said, “Would you be prepared to hold the flag?” She said of course and took the flag out of the box.

I asked her, how would you feel wearing a piece of his clothing in tribute to him? She said, that’s a good idea. She had received a box of his clothing, it was at the base of the bed but she had not yet had the courage to open it. All his clothes, his Army T-shirts were in the box. She said, maybe now is the time to open it.

And then I thought, oh — what am I doing here?

She undid one latch. I undid the other. And as she lifted the lid, she burst into tears.

I felt so ashamed. I really blew it. I thought, for the sake of a photograph, you went too far. I said, “I feel so ashamed. I didn’t want to hurt you. Let’s not do this. This was a bad idea.”

She said, “You don’t know why I’m crying. I’ve just realized they washed his clothes and I wanted to smell him again.” She said, “The pain is there whether I open the box or not. Now the box is open and I think I would like to wear his T-shirt.”

This is not the look of a victim. This is the look of a woman trying to pull all her strength together to face the future.

Have you stayed in touch with Jessica Gray or any of the other people you photographed for this project?

Most were deployed; a few I did have some contact with. In putting together the book, in some cases, I found out some passed away or changed completely. I very rarely seek to have a friendship with the people I work with. Sometimes it happens accidentally. All my attention and affection goes into the work. And my subject knows that. When I’m actually taking the picture, that’s the moment. I know there’s a good chance I’ll never see this person again.

I’ve done some emotional projects before, but not at this relentless pace, day after day. The way I work is, I’m very subjective. I’m not the objective journalist who doesn’t get involved. I’m not the “observer.” How the hell can you be objective when you’re in a widow’s house and she’s standing there in front of you and she’s crying? You can’t. You’re in. You find yourself becoming part of the story in a weird way.

The picture is a complete collaboration between me and the sitter. There’s no stolen moment. It’s a discussion — a visual lesson they are teaching me about life, and I’m just learning it and recording my lessons on film.

This interview has been condensed and edited. Learn more about Platon’s work here: http://www.thepeoplesportfolio.org/

9(MDA1MjcyMDE0MDEyNzUzOTU1NTMzNmE5NQ010))