curiousKC | How Mexican Communities Kept KC Boxcars Cold A window into “La Hielera,” a largely unknown and tight-knit community of laborers and their families from the 1930-40s

Published October 10th, 2022 at 5:37 PM

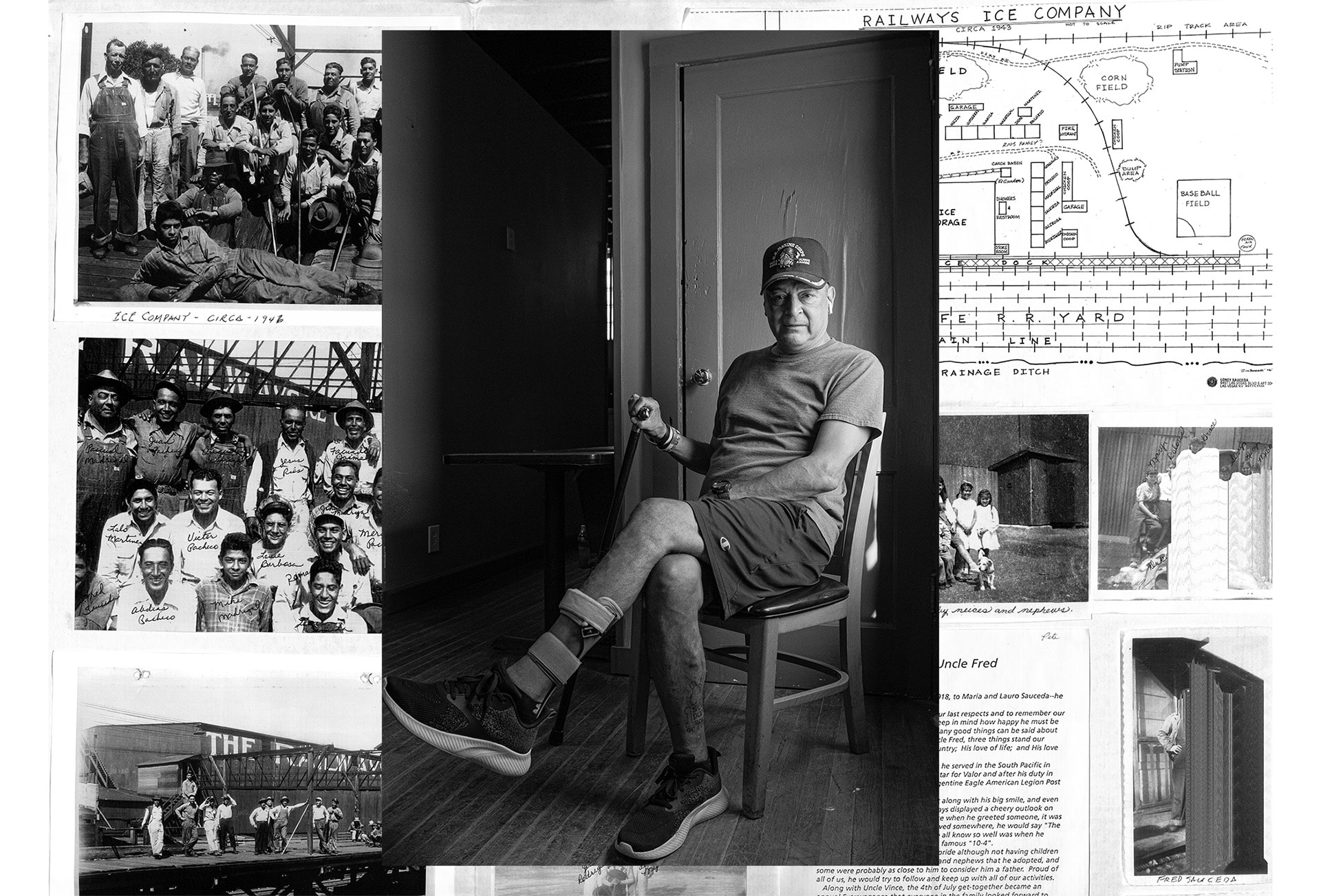

Kansas City native Gabriella “Gabby” Mendez is connected to a piece of regional history that isn’t well known.

Mendez has heard about it from her mom Helen, who turns 90 in December. Stories of a place called “La Hielera,” or the “Ice Plant.”

“She grew up in the ice plant. She talks about it a lot,” Mendez said. “But it is a mystery to me.”

Through curiousKC, she hopes to learn about the history of the plant and how the community her mother lived in came to be.

Helen had fun growing up in the L-shaped row of boxcars between the railroad tracks along the 42nd Street bridge in Kansas City, Kansas.

They called tar-covered shacks home and everything outside was their playground. She was around 5 years old then.

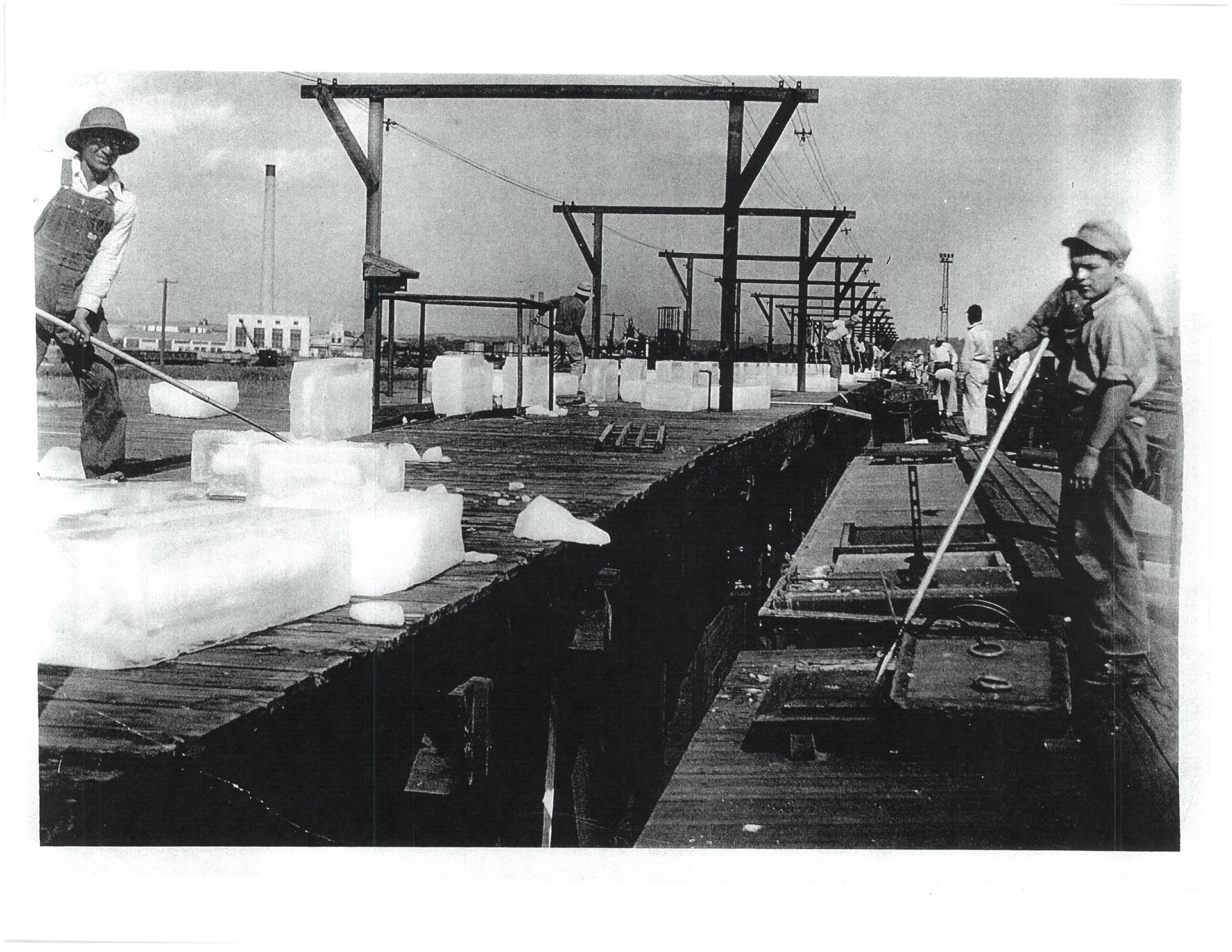

Her favorite memories include exploring the nearby ice plant with her friends and finding all the nooks and crannies of the makeshift neighborhood. One day they wandered inside the warehouse full of whirring machinery. She recalled seeing the ice blocks, as the machines shaved them into perfect rectangles.

“Well the shavings, we used to pick up and make those snow cones or ice cream,” Helen said with a giggle. “We weren’t supposed to be in there.”

Workers like Helen’s father were among the immigration waves otherwise known as chain migration, according to the Smithsonian Institution.

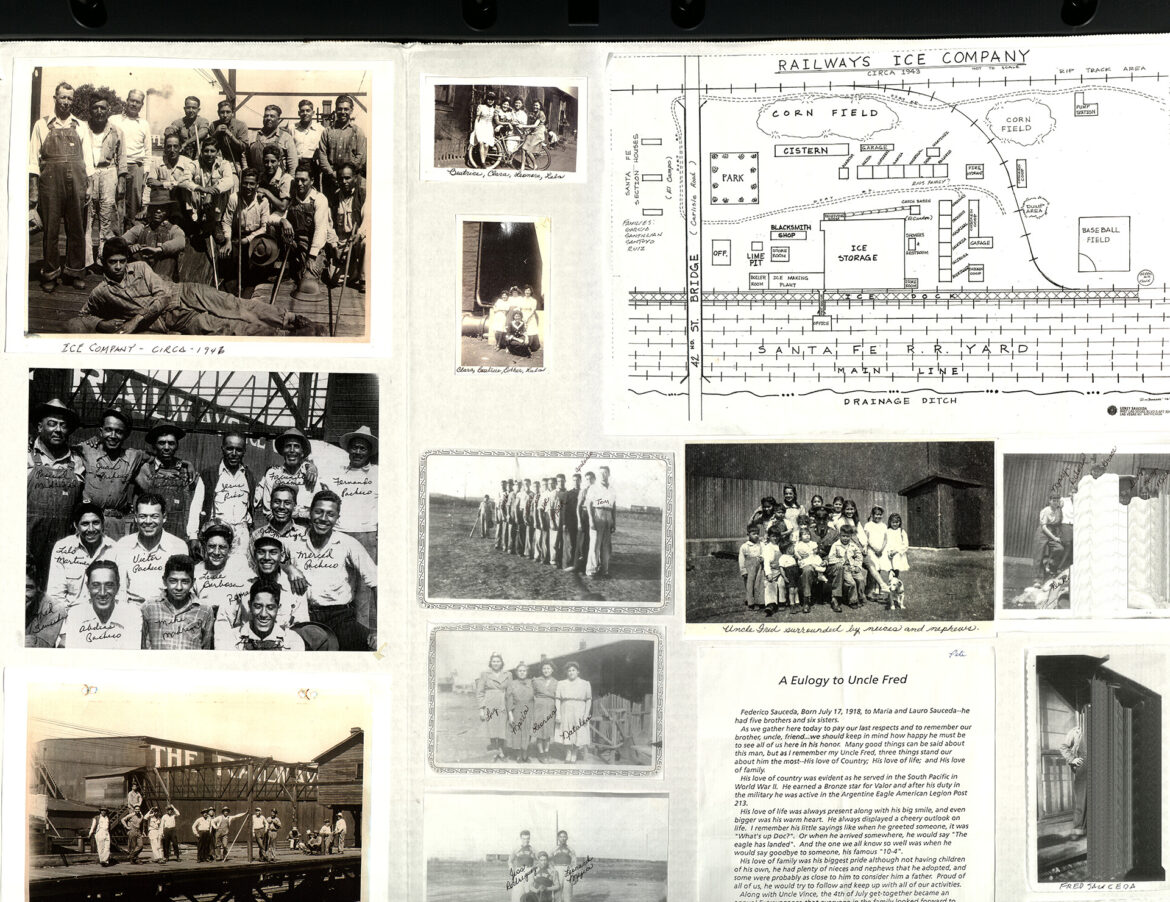

After scouring pages of archived KC Hispanic News articles, historical accounts, oral histories from people who lived there and research articles later, “La Hielera” residents’ stories came to life.

The real story behind why “La Hielera” came to be is, as it turns out, tied to the Midwest’s transportation industry.

The Labor (and Boxcar) Boom

First stop, the late 19th century.

At around that time, railroads began to overtake the Midwest. A booming industry meant new opportunities, but not without sacrifice.

Passed in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese laborers for a full decade from the U.S. During the Golden Age, Chinese workers had been integral to the expansion of the transcontinental railroad system.

So, an influx of Mexican laborers was prompted in part by demand created by discriminatory policies against another ethnic group.

At one point, Mexicans constituted almost two-thirds of the railroad track labor forces in the Southwest, Central Plains and Midwest, wrote the late historian Jeffrey Marcos Garcilazo. His book “Traqueros: Mexican Railroad Workers In The United States, 1870-1930” details their impact.

Research shows that boxcar communities were strewn across the U.S. in major rail hubs such as Los Angeles, Chicago and Kansas City.

During the Great Depression things changed, said Mireya Loza, a Georgetown University historian of Latinx Histories. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, as unemployment soared during the Great Depression, Mexican workers were hit particularly hard by deportation and repatriation.

Loza, who studied these communities as part of her research on Latinx history and labor history, is originally from the Midwest. She explained that Mexican laborers were an important part of the area’s transportation boom.

Though technically ice plant workers weren’t traqueros, those who immigrated and helped build the railroads, they followed closely in their footsteps.

“The people working in the ice plant would not necessarily be considered traqueros, but the reality is the traquero circuit is what most likely brought them to Kansas City, Missouri.”

“They really transform the labor landscape of these Midwestern cities,” she said.

Ice plant workers were a key part of the broader transportation system. Their work kept the produce cold and fresh during the cross-country trek.

“These tracks are pretty important because the tracks actually are not just the physical tracks that take them and transport them,” Loza said. “But they’re also the tracks that actually provide them their first sort of labor entry point.”

When a new wave of industrial development hit, Mexican laborers took up the slack. Employers also adopted a new recruitment incentive. Laborers could bring their families. The company would provide free housing.

“Agencies and employers placed Mexican migrants in temporary and low-paying jobs, often requiring them to live near their place of employment and on the terms of their employer,” wrote Bryan Winston, a historian of Mexican migration and creator of “Mapping the Mexican Midwest.”

Enter Kansas City’s boxcar community.

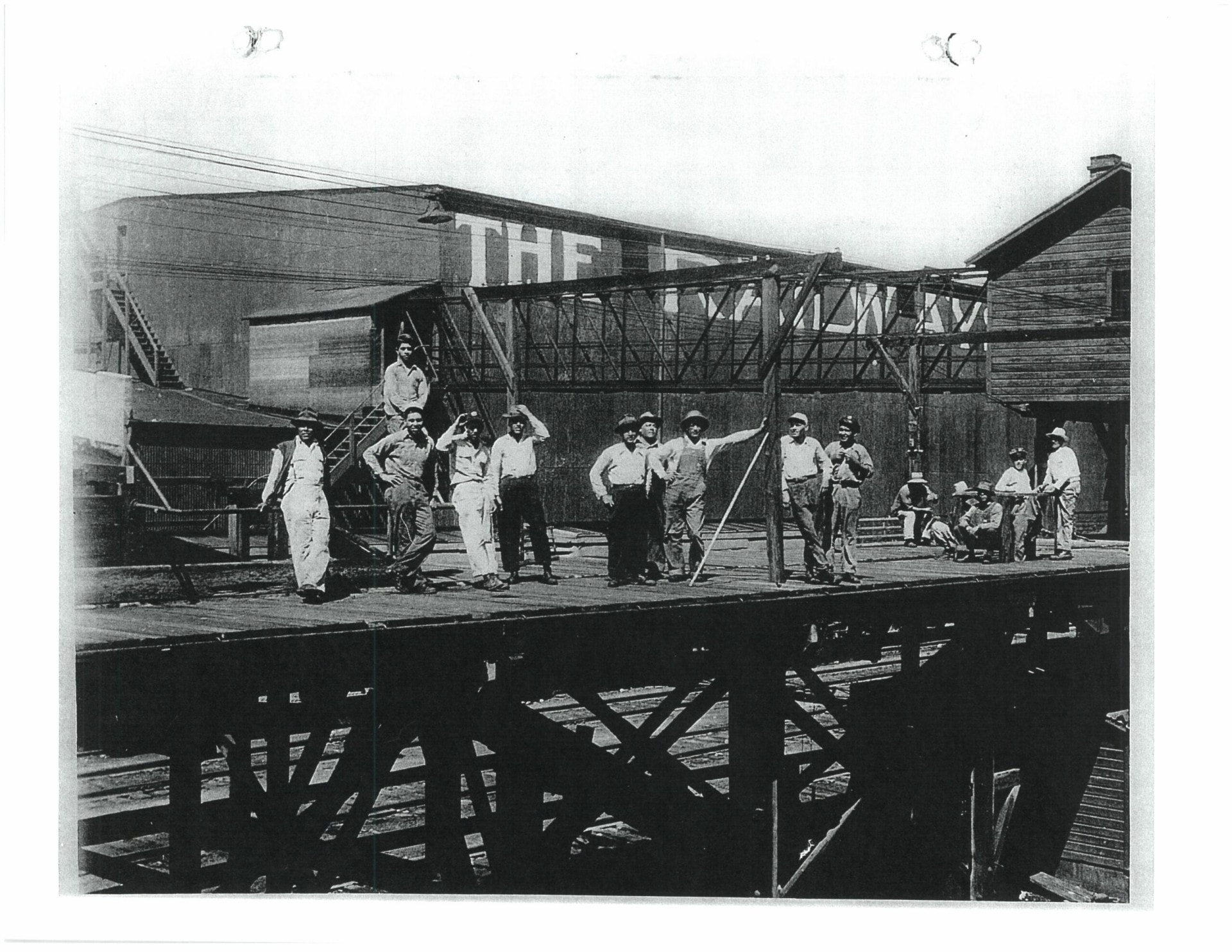

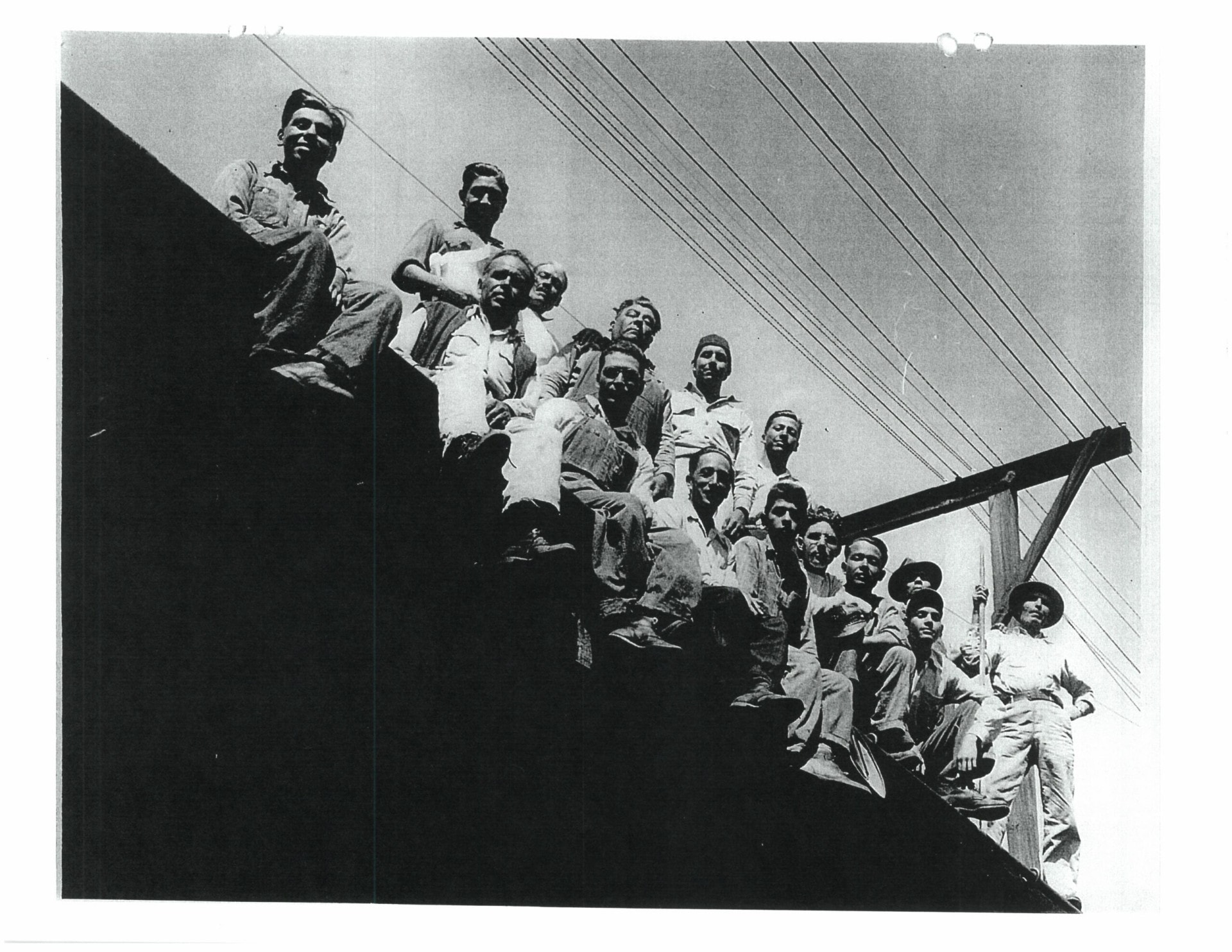

Along the 42nd Street bridge in Kansas City, Kansas, there once was a commune of living quarters and Ice Plant railroad tracks. People who worked for the railroad companies worked around the clock.

So, these laborers and their families built a community. Tin boxes, with no running water and a communal shower.

“Our (houses) were just shacks with black tar paper,” Helen Mendez recalled.

She was one of 10 children, so her house was “mostly beds.” Another “La Hielera” child, Tony Quiroga, a Marine veteran and former ice plant worker, called them cubicles.

Winters were cold and summers were hot, but that didn’t matter much to them.

Helen was content with her family, her friends and her routine. Sunday mass, when she’d dress to the nines in her Sunday best. In the summertime, buy vanilla ice cream from the friendly man driving a white truck.

But life outside of the plant was different.

On days they wanted to see a movie, they’d wander out to the Argentine neighborhood. She would learn that segregated Kansas City put people like her in boxes.

“You know how they do,” Helen explained. “Black (people) in a box and Mexicans in a box, and of course white, they were superior.”

Helen said it didn’t bother her much because she learned to keep to herself and stay in her community. But her brother struggled with rampant discrimination.

For entertainment, kids like Helen or Tony would go to the Park Theater on Strong Avenue in Argentine. That theater was one of the only that allowed Mexicans inside, with some restrictions.

“It was 10 cents and we were separated,” she said. “Mexicans went on the left side. The white people went on the right side.”

Historian Gene Chavez, who has been tracking Latino histories since the late 1960s, is also the son of an ice plant worker from Colorado. Chavez remembers the large tongs used to hoist the ice blocks.

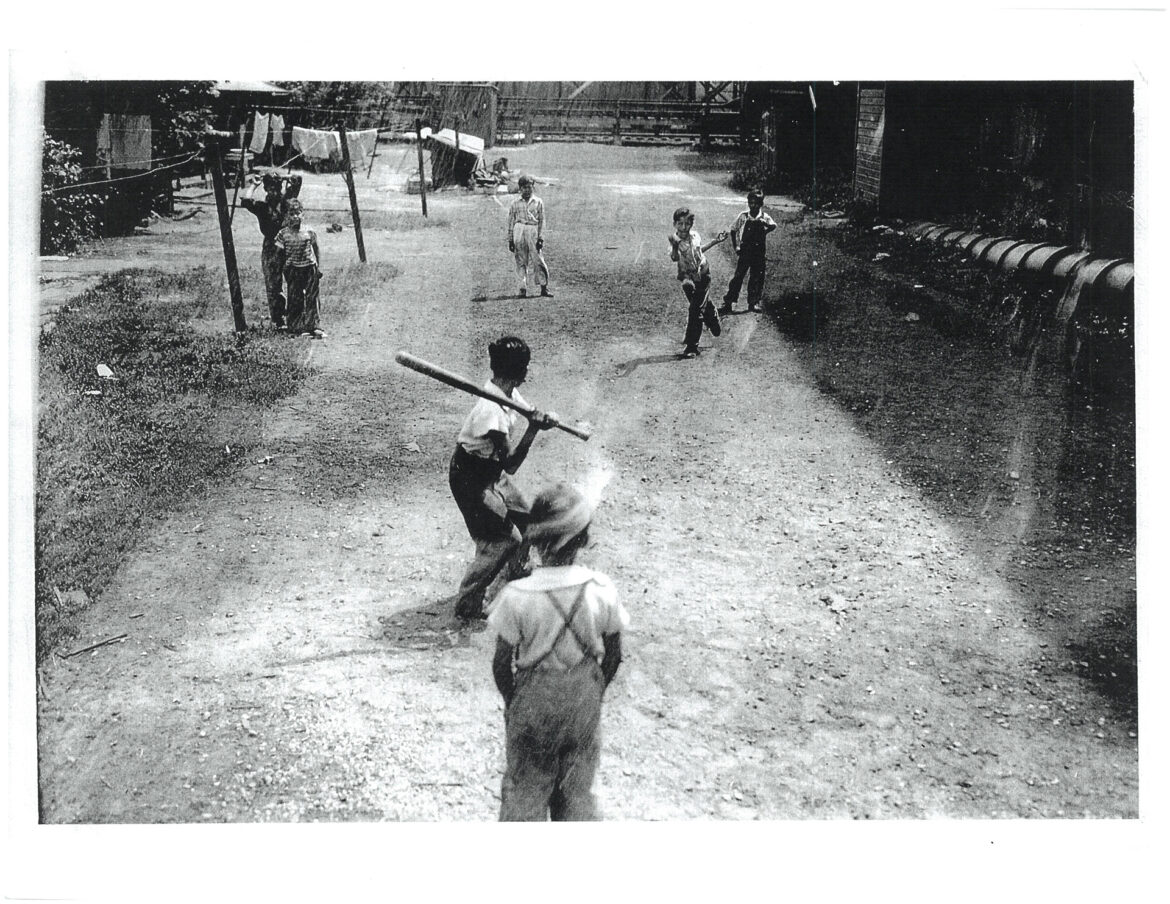

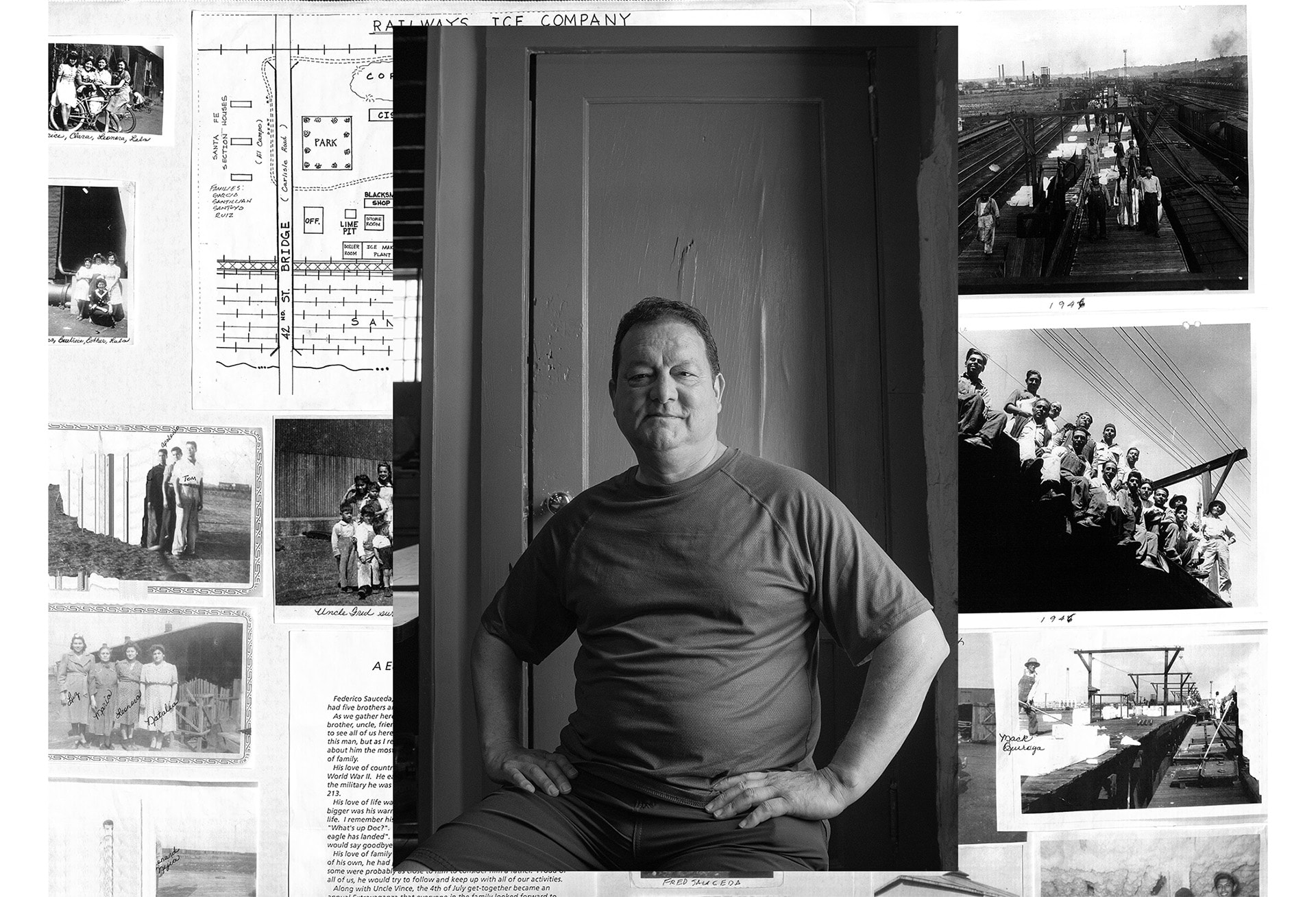

Places like “La Hielera” were micro-communities. Chavez is engrossed by the Eagles Nest community. Flipping through pages of images provided by Tony Quiroga, he begins to expound on the evolution of immigration, labor and military recruitment.

“When they were kids they worked at the ice plant, but then they went to the war,” Chavez said, pointing to a photo of ice plant workers.

Learning these histories is integral to understanding the world today, Chavez said, and he’s dedicated to making sure they aren’t forgotten. Previously, he worked on a traveling Smithsonian exhibit on Mexican baseball teams that began when soldiers returned from the war.

One story cannot be told without the other. Each piece of this history is interconnected, from the rail yards to the baseball fields.

The second stop, inside the ice plant.

An Ice Worker’s Story

The American Legion Post #213 in Kansas City, Kansas, was built for Mexican veterans.

The post, called The Eagles Nest, is cater-cornered to a rail line, a physical representation of Mexican migration and community building in the metro.

It’s a convivial hub for folks like Tony Quiroga, who grew up in the tiny community nestled behind the 42nd Street Bridge and Santa Fe Railroad main line. Quiroga recounted the days he watched his father haul ice. Cumbias play to the backdrop of clinking glasses.

“Our dads worked there. This was during the ‘40s, during the war,” Quiroga said.

Quiroga, a Kansas City veteran, not only lived at “La Hielera.” He was born there, inside a small tar shack. In those days, doctors would do home visits, he explained.

Now in his 80s, he sips a beer and reminisces with fellow vets, their kids and friends.

“La Hielera” – the Ice Plant – was unique. It included 17 families in 17 small shacks.

There was a park. A chicken coop. A baseball field.

“We had to live there 24 hours a day,” Quiroga said. “We couldn’t go anywhere.”

The trains, hauling produce from California or New Mexico, would come and go all hours of the day, he said.

Part of that had to do with the nature of the other. Another was the social climate and ways in which racial groups were segregated around the metro.

He laughs it off now, laser-focused on the photos of his teen father smiling on the dock. One photo in particular shows a group of workers, picks in hand.

Quiroga trailed off about the heavy blocks of his ice his strong father pushed and cut.

“They lugged 300-pound blocks of ice,” Quiroga recalled, his hands mimicking holding the tools he’d later use.

This industry was passed down from one generation to the next. As a young adult, Quiroga took up the tongs as his son looked on.

Families like Quiroga’s and Mendez’s migrated from Mexico. They were first-generation children in Kansas City. It was a small, isolated world, one that’s still felt in the sprawled Kansas City metropolitan area.

“La Hielera” is more than the story of how Mexican laborers kept Kansas City’s produce cold. It’s the story of the people who kept the transportation hub running, growing and thriving.

For people like Helen and Quiroga who grew up — and worked — between the railroad tracks, their stories were part of what built Kansas City’s thriving Mexican community.

“I don’t want this history to be lost,” she said. “It was a good time.”

Vicky Diaz-Camacho covers community affairs for Kansas City PBS.