Latino Community Rallies for Representation at City Hall Renewed Push for a Seat at the Political Table

Published March 22nd, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Crispin Read is one of two Latino candidates in a crowded 4th District at large City Council primary race in Kansas City. (Mary Sanchez | Flatland)Thirty years is a long time to wait for a seat at the proverbial political table.

But it’s been nearly that long since a Latino last held a City Council seat in Kansas City.

It’s been nearly 20 years since anyone even came close to joining the 13-member council, advancing past a primary.

Perhaps more astounding, only two Latinos have ever served on the City Council since Kansas City was incorporated in 1853.

One left office in shame, after a bribery scandal that stymied the aspirations of other potential Latino candidates who could have followed.

The other is former City Councilman Robert “Bobby” Hernandez.

Hernandez is clear on what has been lost for the Latino community since he served four terms, from 1975 to 1991.

“Everything,” Hernandez said.

He launches into a litany of examples, with many of the points echoed by others.

That snazzy new $1.5 billion terminal at Kansas City International Airport? It’s scant on Latino-owned vendors.

Nor is there signage in Spanish, even though Kansas City soon will host the FIFA World Cup, drawing thousands of travelers from Latin countries.

Without representation, there have been fewer chances of seeing Latinos become judges, heads of city departments, Latino-owned businesses tapped for contracts, and countless other large and small things influenced by local government.

At a basic level, a sense of belonging has also been undercut. The Latino community has lost the assurance that someone who intuitively understood their lives would be present when decisions were made on development, funding and the day-to-day functioning of Kansas City.

“Absolutely, you need people that are sensitive and understand the needs of the Latino community,” said Beto Lopez, president and CEO of Guadalupe Centers. “Without it, it’s like you have to, you know, beg and scratch and claw just to get peanuts.”

Instead, there has been a concentration on forming alliances and nonprofit leadership advocating on the community’s behalf issue by issue, but without an elected representative to carry concerns to the full council.

John Fierro, who ran for the 4th District seat in 2005 before losing to former state senator Jolie Justus, agreed.

“Because we haven’t had City Council members, or consistently, people on the Jackson County Legislature, or even a Missouri state representative, we have not received the resources that we have needed over time to address education, health care, economics, etc.,” said Fierro, President and CEO of the Mattie Rhodes Center.

The lack of Latino elected officials is noteworthy in a city where the demographic is nearly 11% of the population, or about 55,000 people, and with a rich history.

Those numbers are likely a low estimate, as Latinos are believed to be undercounted in Census figures.

Latinos locally represent a vast range of backgrounds and experiences, including new immigrants, those with multi-generational roots in Kansas City, many of Mexican descent, and a growing Central American population, in addition to Cuba and many South American countries.

Looming Elections

By summer, there’s hope that a watershed event in Latino political representation will occur in Kansas City.

Two Latino candidates are vying for the 4th District at-large City Council seat on the April 4 primary ballot.

Crispin Rea and Gresia “Grace” Cabrera are two of the five people in the crowded 4th District race. Katheryn Shields is finishing her second term in the seat.

Rea, who is a Jackson County prosecutor, has the backing of many in the civic, nonprofit and politically active circles among Latinos in the metro.

Rea grew up on the city’s East Side. He’s a former member of the Kansas City School Board and lives in the Valentine neighborhood with his wife and child.

He’s drawn the endorsement of Freedom Inc., Southland Progress and many local unions.

Cabrera, who immigrated from Cuba to Kansas City as a child, represents the ever-widening circle of local Latino diversity, beyond those of Mexican descent.

She lives with her parents in the city’s historic northeast area and recently joined Humana, helping customers connect with care. The Cabrera family was exiled after her father, a minister, was imprisoned. He chose Kansas City as a resettling point, having been enthralled with the idea of seeing the Missouri River and heartland fields by reading Mark Twain’s books.

While Latinos strive for representation on the City Council in Kansas City, they are making gains in other parts of the metropolitan area.

In November, Manny Abarca , a former member of Kansas City’s school board, became the first Latino on the Jackson County Legislature in nearly a decade.

There’s also a growing presence of Latinos serving in the region’s suburban cities, with Latinos serving on the city councils of Lee’s Summit, Overland Park and Lenexa.

Lopez, of Guadalupe Centers, is Lee’s Summit’s mayor pro tem.

In part, that reflects the fact that Latinos aren’t necessarily concentrated in one portion of the city — they live everywhere. Moreover, they hold a variety of political viewpoints.

Another experienced Latino candidate might be added soon to a suburban city’s government.

Theresa Garza is running for the Raytown Board of Alderman. She’s a former Jackson County legislator, holding office from 2006 to 2015. Garza, a Navy veteran, then ran for City Council after she served in the legislature, but withdrew before the primary.

Latinos have also served in other prominent roles, such as the Parks and Recreation Board of Commissioners.

But the Kansas City Council looms as the most prized political body that has been without a Latino representative for decades.

Many are backing Rea, hopeful that he’ll be one of the two candidates moving forward from the April primary to the general election on June 20.

Also seeking the at-large 4th District seat are Jess Blubaugh, Justin M. Short and John D. DiCapo.

Regardless of who prevails, plans are being formed to host a post-primary forum for the winners of the April ballot.

Latino civic leaders from nonprofits and the business community will take part.

The idea stems, in part, from when local business and philanthropic leader CiCi Rojas was president and CEO of the Greater Dallas Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. She is also president of The Latino Coalition, a national membership organization of U.S. Latino businesses advocating on public policy issues.

In Dallas, all candidates took part in discussions about their plans for Latino inclusion and the economic prosperity of the city.

“Yes, we want you to be the best advocate for the city, but we are also looking at this from the viewpoint of the Latino lack of representation,” said Rojas, partner and president of Tico Productions. “In the absence of that, how are you going to represent our community to make sure that we are not left behind?”

One Falls, A Community Hurts

Handpicked and groomed to represent the predominantly Mexican American population, Michael Hernandez won a coveted seat on the City Council in 1991.

Then, he disrespected himself, the leadership behind him and the hopes of an entire community.

Hernandez was indicted in a bribery scandal that ended his political career and shattered the community’s belief that they could be fairly represented in city government.

It was personal to many who had backed him.

They canvassed for him, raised funds for him, and of course, voted for him.

Hernandez was groomed to be the replacement, the successor to the seat that Bobby Hernandez had long held.

The men are not related. They simply share a common Hispanic surname.

But new rules, term limits, had removed Bobby Hernandez from office, a change that also affected a long-serving African American council member, the late Charles A. Hazley.

Michael Hernandez was indicted in 1995 and later pleaded guilty to accepting $70,000 in bribes from a developer, in exchange for reducing costs associated with planned housing development near Line Creek Parkway.

The developer who paid the bribes also served time.

Hernandez was sentenced to 15 months and later stayed out of the public eye, working in international education for college students.

“From my perspective, it just destroyed our credibility north of the river,” Bobby Hernandez said. “That is not reflective of our community. We’re not people that take advantage of the situation.”

The mid-90s saw other politicians also leave office in scandal. Several other council members were also indicted and convicted, Black and white.

Perhaps most notably, Bob Griffin, the longest-serving Missouri Speaker of the House, was forced from office with a conviction on bribery and mail fraud. Griffin died in 2021.

But within Latino circles, some felt their scandal tainted the community.

“Remember the world views and thinks in colored glasses,” said Bobby Hernandez. “They don’t see things like we see things. Mistakes from minorities appear brighter than mistakes from white people.”

In the ensuing years, there has also been a misplaced belief Latinos are politically monolithic, Fierro said, with the idea that all Latinos need to be behind one candidate.

As a result, any whiff of dissent or disagreement gets amplified in the broader community, as if race supersedes all other considerations.

“I think that … discourages individuals from running and then what ends up happening is you don’t get some broad support, because individuals are more fixated on, ‘Oh, not all of the Hispanic community is behind Juan Sanchez,’” Fierro said, using a made-up candidate name.

Redistricting — including the fact that Latinos aren’t necessarily concentrated in one part of the city, although the Westside and the Northeast have been strongholds for decades — also hurts.

Stepping Up

Others noted that older Latino generations might have been more hesitant to step up and ask for the type of donations that are necessary to launch a campaign today. It’s an aspect of culture, some said.

But that mindset is changing.

“You can always have allies, but that’s a different story than having, you know, an actual person who has connections in the community,” Garza said.

Like elsewhere in the U.S., Latinos here are continuing to increase numerically and diversify.

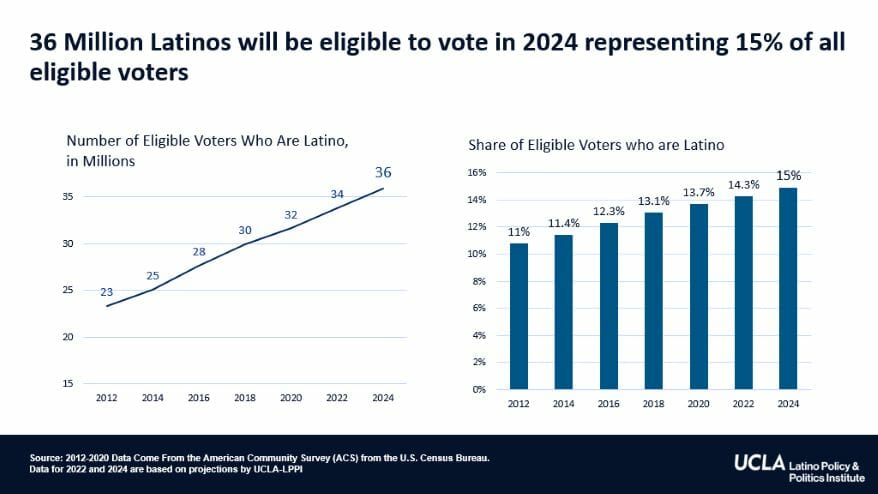

Guatemalans are the fastest-growing Latino group in both Missouri and Kansas, according to a 2022 study by UCLA’s Latino Politics and Policy Institute. Additionally, more than a million Latino citizens turn 18 every year in the U.S., indicating their potential power at the polls.

With the Kansas City primary approaching, there are more discussions about the earlier pioneers from the community who held office before the gap years of representation at City Hall and at the county legislature.

The names are often mentioned with reverence: I. Pat Rios, Paul Rojas, Carmen Xavier and the lesser-known faces who diligently worked the polls and went door-to-door, investing in those candidacies.

“The Latino population was much, much less significant back then and they got elected to state rolls,” Lopez noted of people like Rojas, who in 1972, became the first Latino elected as a state representative.

Rios (1973-78) and Xavier (1983-86) served on the Jackson County Legislature. Xavier now lives in Smithville and has continued to be active politically, running (unsuccessfully) for the school board, but then being appointed to the planning and zoning commission.

“My presentation politically when I lived back on the West Side was demonstrative. And the times, I think, demanded that,” Xavier said. “And up here, it’s more communication and cooperation with an eye toward positive change.”

Smithville is more conservative, she said.

“I’m a Hispanic first, who happens to be a trans woman,” she said, noting that she has no qualms with citing her former name, Fred Sanchez, which is how she was known as a county legislator.

Stories of mentoring, connections between past politicians and those running now, are common.

For years, Rafaela “Lali” Garcia, was known as the “Queen Bee,” a vital force behind the La Raza Political Club.

Garcia died in 2021.

Her impact is noted in conversations surmising about La Raza’s future and the type of sustained effort it will take to get more Latinos elected.

“We have a number of really strong leaders in business and nonprofits,” noted council candidate Rea. “But it has just been very challenging for folks from our community to get elected.

“You hear how much representation matters,” he continued. “I want representation for the Latino community to matter.”

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS.