Zero KC Wants to End Houselessness in Five Years But Will Require More Commitment from Leaders Prior to the action plan, advocates and nonprofits working with houslessness communities received minimal support from the city. They hope to see this change.

Published October 13th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Members of Kansas City Heroes, a local nonprofit, serving a free meal to unhoused individuals on Oct. 4. The organization hosts this dinner every Tuesday in Washington Square Park. (Zach Bauman | The Beacon)In her five years of helping people who struggle in Kansas City, Alina Heart has come to understand many of the factors contributing to a sharp rise in houselessness.

The end of COVID-19 relief funds and eviction moratoriums, in combination with rising inflation, has sent many people over the threshold, said Heart, who volunteers with Kansas City Heroes, which promotes “small acts of kindness” to vulnerable individuals and communities.

Simply put, need outpaces resources, she said, “like the vouchers for rent only go up once a year versus rent, which can go up monthly in this town.”

“Landlords are reluctant to provide housing to people without a credit or rental history, or to those using housing vouchers,” Heart said. And the housing that people on the margins can secure is often unsanitary, inaccessible and unsafe, especially for people who have had the traumatic experiences that can accompany houselessness.

“There needs to be an emphasis on housing that suits the needs of the traumatized people, too,” Heart said. “Putting somebody with social anxiety or PTSD in a large apartment complex probably isn’t the best solution for them.”

On Sept. 22, Kansas City leaders announced they would try to address the needs that Heart sees in her work with a five-year plan to end houselessness that they’re calling Zero KC. Some funding for the effort would come from a $50 million bond package that will go before the city’s voters on Nov. 8.

“The city didn’t really have a plan for addressing homelessness in the past,” said Ryana Parks-Shaw, the 5th District councilwoman and chair of the city’s houseless task force.

At least 711 persons are currently unhoused in Kansas City, according to Zero KC. This is a sharp uptick from the 408 known unhoused individuals in 2021. City officials and others attribute the rise to a critical lack of available and affordable housing units, shortages in service provider staffing and the long stretch of time it takes to get an individual or a family into permanent housing.

Zero KC lays out a strategic approach centered on five pillars to get people into housing. The plan was designed to be flexible and adjusted annually.

“We know that it’s not one size fits all, everybody has their own specific issues. And so the focus of this is really trying to meet those individuals where they are, then providing them with the services and resources that they need to help them be sustainable,” Parks-Shaw said.

The foundation of Zero KC comes from the Built for Zero program, a movement of more than 100 cities working to solve houselessness. It uses a metric called “functional zero,” meaning the number of people experiencing houselessness at any time is less than the number of people exiting houselessness and finding stable housing.

Kansas City has already been able to reach functional zero with its unhoused veteran population, Parks-Shaw said. Nonprofit groups have stepped up to provide shelter and services for veterans in recent years.

The Zero KC resolution approved by City Council calls on City Manager Brian Platt to draw up a detailed plan for the council to vote on again at a later date. Advocates and unhoused individuals, who have spent years urging the city to do more to provide housing and services, are watching to see if leaders are genuinely committed this time.

Renters Need Affordable Housing

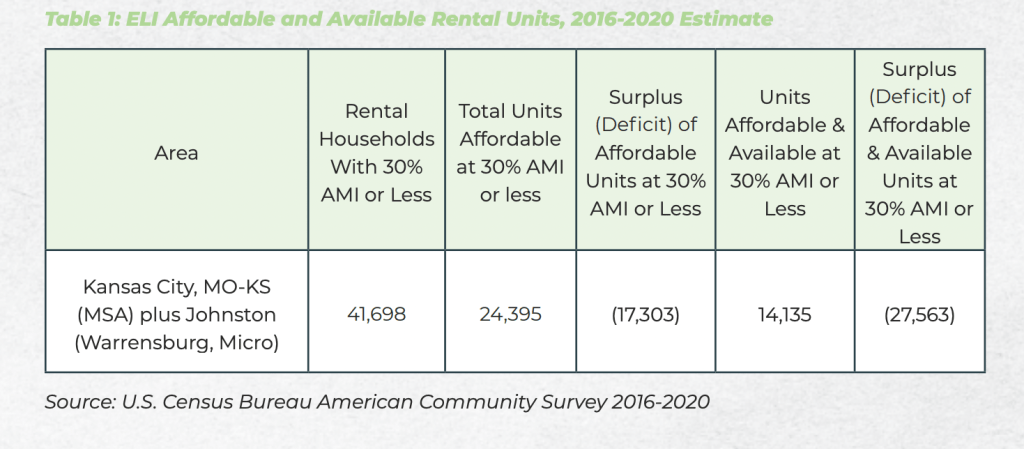

In Kansas City, more than 41,000 renters make 30% or less of the area median income, which is currently $96,800 for a four person household, but fewer than 25,000 units are affordable to families in that pay range, according to Zero KC. That amounts to a shortage of 17,303 extremely affordable units.

Additionally, service providers are short at least 75 emergency housing units and even more shelter beds.

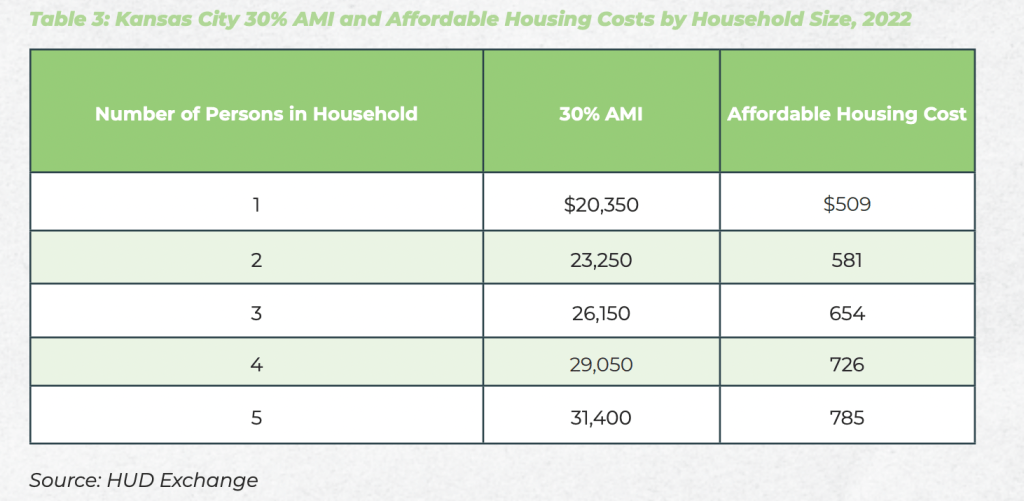

In a recent controversial move, Kansas City Council changed its affordable housing ordinance, getting rid of the requirement that developers who receive incentives must provide a minimum number of extremely affordable housing units. Instead, the city now requires that 20% of housing units be within reach for households making 60% of the area median income, or nearly $1,200 for a one-bedroom apartment.

Yet, households that pay more than 30% of their monthly income for housing are unlikely to have sufficient resources left for other necessities such as food, transportation and health care.

Extremely low-income households are so cost-burdened that they are at risk of homelessness from something as simple as an unexpected expense or a loss of working hours due to illness.

In response, Zero KC has committed to increasing affordable housing for vulnerable households by producing 300 extremely affordable units a year for the next three years.

These new developments will be funded by way of the Affordable Housing Trust Fund, which leaders hope voters will boost in November by approving the issuance of $50 million in general obligation bonds.

The city is also applying for federal applications and grants to fund affordable housing.

In years past, Kansas City has received $18 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for its Continuum of Care program, which distributes funds among different agencies and shelters assisting unhoused people. According to Parks-Shaw, it has not been enough.

Zero KC Calls for Collaboration

Volunteers who work with unhoused people often talk about a disconnect among the groups and institutions doing the work. They say that nonprofits and institutions work in isolation or in small groups with limited funding and support from the city.

“You’ve got all these volunteers that are doing all of this free work that the city needs to be helping with,” said Jennifer McCartney, the founder of KC Heroes. Her nonprofit does not receive any funding from the city to conduct its events, drives or dinners. Instead it relies on contributions from volunteers and donors. Currently the organization is accepting donations of blankets to support the unhoused through the winter.

McCartney said she is feeling the pressure of trying to assist thousands of people with limited resources.

“We’re regular people that are spending money out of our own pocket to do something our city needs to help with. We can’t do all of that, there’s thousands of people in the downtown and midtown area. We’re just one little nonprofit.”

Zero KC plans to emphasize collaboration among organizations that help the homeless.

“There’s a commitment from all of us to work together to really address the issue,” Parks-Shaw said.

The fragmentation of the city’s approach to houselessness has had consequences in the past.

In 2021, Kansas City invested $8.5 million in COVID relief funding for community organizations to provide housing, emergency shelter, outreach and other assistance to residents.

“We never saw any of that,” McCartney said. “It was for emergency stuff, but it never got used. To this day, we haven’t heard if it’s gotten used.”

Parks-Shaw admits that the city did not handle the funds properly.

“We didn’t really have a firm plan,” she said. “We were reactive in distributing funds, and probably could have been more efficient with the way that we spent those funds.”

Now, instead of funneling just enough money to organizations to help a small number of people, the city will focus on specific strategies that can impact more people, Parks-Shaw said.

“With an actual plan and strategy, we can be more focused and targeted on how the dollars are spent.”

More Caseworkers and Services are Needed

Another recognized need is for more staff at the city and organizational levels.

“It’s almost impossible to get housed without having a case manager, but like social service workers, there are very few of them,” McCartney said.

“We need more money put into caseworking programs,” she said.

Steave, a currently unhoused man who attends a weekly dinner in downtown Kansas City served by KC Heroes, said that different people have different needs and more caseworkers or counselors are needed to serve the large houseless community.

“Right now, you’re just putting Band-Aids on everything until you get down to the core problems, and that means a guidance counselor on an individual basis for each one of these people,” he said.

“Everybody’s got a different story. Most people just want their story heard.”

Even bigger organizations are confronting staffing shortages. City Union Mission, an evangelical ministry and one of the city’s biggest shelters for unhoused people, can currently serve up to 300 people. During the winter, it always reaches capacity and sometimes takes in even more people.

“That number will probably go up by another 50 to 100,” said Terry Megli, the CEO of City Union Mission.

“We would love to take an additional 50 more men during the winter, but that requires us to acquire more staff.”

City Union Mission is currently raising funds to support those increased operational costs.

Looking Towards the Future of Zero KC

The city’s work on Zero KC is taking place in the midst of other developments related to the unhoused population.

A bill signed over the summer by Missouri Gov. Mike Parson will ban homeless people from sleeping on state-owned property starting on Jan. 1, 2023. Cities that don’t enforce the ban risk being sued by the attorney general and losing funding for housing services.

Kansas City officials, including Mayor Quinton Lucas, have condemned the bill for criminalizing individuals who are without a fixed place to stay. The houseless task force has been working with the city’s legal counsel to break down the details of the law and its impacts on Kansas City, Parks-Shaw said.

Zero KC also details plans to restructure city operations to focus on housing, engage neighborhoods and businesses around solutions, and create low-barrier shelters with no religious-based expectations or other features that may deter people from staying.

Those most impacted, however, remain skeptical about the city’s commitment to the houseless community.

“They need to get out here to get face to face with people. Quit worrying about your prestige, quit worrying about your face on TV,” said Richard Johnson, who said he was unhoused for 13 years until just recently.

In Johnson’s opinion, the city spends too much time assessing needs instead of responding to them.

“Every time they try to do something they have to study. Every study takes three to four months,” he said.

“They need to be proactive on the street. Forget studying. Go sleep under a bridge, go sleep on a park bench. Stay one night and see what it feels like.”

Mili Mansaray is the housing and labor reporter at The Kansas City Beacon, where this story first appeared. The Beacon is a member of the KC Media Collective.