Study Finds Many ‘Maternity Deserts’ in Kansas and Missouri Both States Rank Below Average in Access to Obstetric Care

Published November 8th, 2022 at 6:05 AM

Above image credit: A new March of Dimes study concludes that both Kansas and Missouri are below the national average when it comes to the presence of "maternity deserts." (Creative Commons-Pixabay)Missouri Highlands Healthcare operates health clinics in seven counties in southeastern Missouri, four of which are considered maternity deserts.

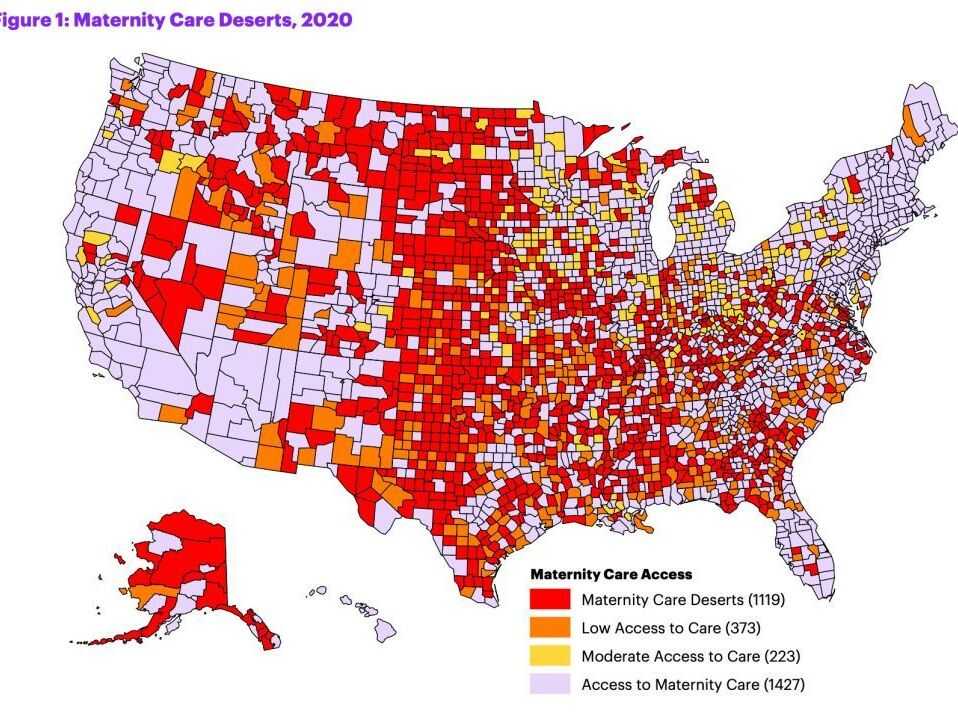

The term comes from the March of Dimes annual list, identifying counties that lack obstetric care. To qualify as a maternity desert, a county has no hospital obstetric care and no obstetricians or gynecologists (OB/GYNs).

About half of the women in these rural maternity deserts have to travel more than 30 minutes to reach a hospital with obstetric services (compared to just 7% in urban communities), according to the March of Dimes report. This lack of access contributes to a range of issues for mother and baby including increased risk of preterm birth and higher morbidity and mortality.

According to Karen White, CEO of Highlands, the landscape may be even more bleak. The nearest delivery sites that work with high-risk patients in White’s region are St. Louis and Cape Girardeau.

“It can be over an hour’s drive in many locations in our area to the nearest hospital (with obstetric services),” White said. “That can mean life or death when it comes to difficult pregnancies.”

Distance and Complications

In Missouri, 47% of counties are maternity deserts and another 22% have moderate to low access to OB/GYN care (which could mean as little as one OB/GYN or birthing center). Kansas is slightly higher, with 48% listed as deserts and 24% with low access.

Nationally, 36% of counties are considered maternity deserts, and they are home to a total of 2.2 million women of childbearing age. In the Kansas City area, local maternity deserts are Ray, Miami, Linn and Doniphan counties.

In addition to major pregnancy complications leading to death, living far from a health care provider or hospital with obstetric services can make a pregnancy challenging in many ways.

March of Dimes did some mapping across the country to determine the rates of chronic disease among women of maternal age. Where access is lower, women tend to have higher rates of chronic health conditions like asthma and hypertension, said Elizabeth Lewis, director for maternal and infant initiatives in Kansas and Western Missouri for March of Dimes. These conditions that complicate pregnancy are more likely to go unnoticed if someone misses prenatal appointments because of the drive.

Distance can also make it more difficult for women to get prenatal and postnatal services like the ones offered at AdventHealth in Overland Park. The hospital is the closest delivery site for women in the north part of Miami County. About 15% of the hospital’s births are from Miami County residents, said Jessica Mackie, leader of maternity services at the hospital. Advent offers on-site services including educational and birthing classes for expectant mothers and a lactation clinic for new moms.

Alison Williams, vice president of clinical quality improvement at the Missouri Hospital Association, said it’s just not feasible to drive an hour for prenatal appointments for many moms who are young, single, managing multiple children, have a full-time job or have no transportation.

“Because of those barriers we see they don’t get as much, or any, prenatal care and don’t get supports and interventions they might benefit from,” Williams said. “They come in and their blood pressure is already really high, which can create long-term health outcome issues.”

More intense problems during labor can lead to a mother needing care in an intensive care unit (ICU) or transfusions. Preterm babies may need care in a neonatal ICU. Many small hospitals in rural areas offer primary and emergency care or act as stabilization centers.

“In parts of Kansas, that can mean going two-and-a-half hours to three hours away for a hospital that can handle preterm labor,” said Mariah Chrans, project director of Cradle Kansas City, an initiative that addresses infant mortality in the metropolitan area. “They may have to drive for an hour in labor, which can be scary. And what if there is a problem? Do you stop driving or wait for an ambulance, which can take even longer?”

The March of Dimes also publishes report cards that grade each state on their premature birth outcomes. In 2021, Kansas received a C and Missouri received a D. According to the organization, in 2020 about 15% of women in Missouri lacked appropriate prenatal care, and 10% did in Kansas.

“Missouri consistently ranks in the nation among the highest maternal mortality in the country,” Lewis said.

Rural Majority

Though urban areas can suffer from a lack of OB/GYN services, many of the counties in both Kansas and Missouri dealing with this issue are rural. And many of these communities also suffer from a range of disparities that only exacerbate mothers’ and babies’ health challenges.

According to White, 80% of the pregnancies in southeastern Missouri are high risk (as opposed to about 20% among all pregnancies nationwide). Several factors contribute to that, including generational poverty and lack of education and transportation. Substance use is high, even among pregnant women. And patients have high rates of diabetes and hypertension

“In the middle of nowhere – which is where we are at – providers don’t have a ton of resources, but there are a lot of high-need patients,” White said. “Sometimes we look around and ask, ‘What third world country are we in?’ But no, it’s just rural Missouri.”

“In the middle of nowhere – which is where we are at – providers don’t have a ton of resources, but there are a lot of high-need patients. Sometimes we look around and ask, ‘What third world country are we in?’ But no, it’s just rural Missouri.”

Karen White, CEO of missouri Highlands healthcare

Because of the compounding health challenges in Highlands’ regions, White said their goal has been to focus on increased access for high-risk populations. To do so, they received a federal Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies grant.

Last year, during their first year of funding, Highlands implemented home visits for high-risk mothers, one-on-one nurse care manager visits, and a telehealth link to a maternity fetal medicine specialist in St. Louis from their Poplar Bluff location. They employed remote blood pressure monitoring for women with hypertension and trained area clinics on fetal monitoring. They also provided treatment for pregnant women with substance use disorder at five of their clinics.

“There’s been lots of learning as we go,” she said. “We’ve never done this, and it doesn’t have to look like anything in the past. We can take best practices and make educated and evidence-based changes in how care is delivered.”

On the other side of the state, Jeff Bloemker has a different plan for his maternity desert.

As the newly minted CEO of Ray County Memorial Hospital in Richmond, Missouri, his goal is to open a birthing center for the community, which has just over 23,000 people and is located about 30 minutes northeast of Kansas City.

“We should have that here. It’s one of the things people expect in a peri-urban community,” he said.

The county has no obstetric providers and the hospital doesn’t have OB/GYN services. There were 264 births in the county in 2020. Since 2019 there have been three emergent births at Ray County Memorial.

Because his county is different from White’s, his goal is to bring back basic OB/GYN services. There is a large Amish population in Ray and he said many families prefer midwifery care, he said. They could send high-risk pregnancies elsewhere, but he thinks a birthing center with a midwife could handle most of the county’s needs.

Though he is only two months into his job, he has already met with a certified nurse midwife to see what a birthing center might look like at Ray County Memorial. There are two buildings on the campus that are mainly vacant that he said would be well-suited for that purpose.

“We have the property, we have the number of births to support it here and in outlying areas, it’s just getting the state of Missouri to become more friendly with midwifery in an independent practice,” he said.

Missouri allows midwives to practice, but only under a doctor’s supervision. Legislation allowing midwives full practice authority, the ability to practice without a physician on site, was passed in Kansas in April.

Lewis said this was a win for the state but didn’t solve all of its issues. Kansas hasn’t passed Medicaid expansion, which could bring income for providers in rural communities, which tend to have higher Medicaid populations. And the amount Medicaid reimburses for midwife deliveries hasn’t changed in 20 years, she said.

Seeking Solutions

Increasing the use of nonphysician providers could also include training local primary care providers to perform prenatal care for low-risk pregnancies and training emergency medical service providers in emergency obstetrics.

March of Dimes has begun placing mobile health units in some areas across the country. Group prenatal education is also an option that allows a smaller number of providers to reach a larger number of patients. It can also create peer support for women in more isolated areas.

The number of maternity deserts is growing annually as rural hospitals close. A 2018 Health Affairs article found that 9% of rural counties lost all obstetric hospital services between 2004 and 2014. This is likely a combination of low reimbursement rates for providers and the high costs of anesthesia and malpractice insurance. Williams said obstetric units need to be equipped like an operating room, emergency room and an intensive medical unit.

For now, women in maternity deserts will have to rely on hospitals like Advent moving to the southern parts of suburbia for care. The hospital has eight labor and delivery rooms and expected about 30 births a month when it was built a year ago. They are already exceeding that, anticipating they will hit 40 monthly. They have room to build out and are planning to do so soon.

“Specialty access of all kinds is an issue in rural healthcare, but we are committed, as an organization, to making sure there are options for moms,” said Morgan Shandler, Advent’s media specialist. “We may not be able to have a birthing center in the county, but hopefully we can provide connection points and easily accessible care.”

Tammy Worth is a freelance journalist based in Blue Springs, Missouri.