‘The Beverly Hillbillies’ Backstory New Book Illuminates Life of TV Pioneer from Independence

Published October 2nd, 2017 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Ruth and Paul Henning, along with their kids, wished friends a Merry Christmas from their home in Southern California with a card that included a similar family pose each year.Ruth Henning couldn’t find the one book she wanted to read.

So, like a lot of writers before her, she wrote the book herself.

That book, “The First Beverly Hillbilly: The Untold Story of the Creator of Rural TV Comedy,” is a newly published memoir of Henning’s husband, television producer Paul Henning, who grew up in Independence, Missouri, and moved away to find fortune, and maybe not quite an equal amount of fame, in California.

Published last week by the Jackson County Historical Society and the Mid-Continent Public Library, the book offers a little bit of everything: history, gossip, social commentary and a modern twist on our public libraries.

Most importantly, perhaps, the book serves as a catalyst to revisit the life of Henning, whose creative genius has been overshadowed by another local product of that time: Walt Disney. One scholar has even called Henning one of the most influential figures in television history.

Ruth Henning died in 2002; Paul Henning in 2005.

“Our mother always felt Daddy didn’t get nearly the appreciation he should have gotten,” Linda Henning, a daughter of Paul and Ruth, said during a recent interview from California.

“But even though my father was a self-made man, he always kind of played down what he did,” she added. “My father was introverted, very quiet and shy.”

Paul Henning was the creator of “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

That might not mean much to this generation of television viewers, though reruns of the show still run on cable stations in Kansas City, but it speaks volumes to the legions of people who still remember it as a smash hit from the 1960s.

“Hillbillies” ran for nine years. It became TV’s top-rated program after its 1962 debut and, through 1964, averaged 57 million viewers. It also inspired two similar successful comedies, “Petticoat Junction” and “Green Acres,” both set in the fictional Hooterville and featuring gentle send-ups of rural life.

Fans of “The Big Bang Theory” and “Modern Family” probably don’t realize it, but those programs might be considered contemporary variations on the situation comedy format Henning helped refine 55 years ago last month.

“Hillbillies” chronicled the adventures of the Clampett family, which moved to Southern California after patriarch Jed’s stray rifle shot uncorked a subsurface oil field on his rural hardscrabble property.

Comedy came in the subsequent collision of cultures.

The continuing down-home fascination the Clampetts had for the pool behind their Beverly Hills mansion — which they continually mistook as a “cee-ment pond” — comforted viewers during the upheaval of the 1960s, Linda Henning said.

What is still considered one of the most watched half-hour broadcasts in television history — in which Granny mistakes a kangaroo for a huge jackrabbit — appeared on Jan. 8, 1964, several weeks after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“I used to get fan letters from people who wished that their home was like ours,” said Linda Henning, who played Betty Jo Bradley on “Petticoat Junction” for that show’s almost seven-year run.

“Kids would come home from school and play ‘Petticoat Junction,’ portraying the different characters. These were people they felt a kinship with, and I think that was important, especially during the 1960s.”

Paul Henning and Ruth Barth — a 1930 graduate of Central High School — met at KMBC, where they wrote and acted in daily rural-themed serials known as “Happy Hollow” and “Life on the Red Horse Ranch.”

Ruth Barth in the 1930 yearbook from Central High School in Kansas City.

As detailed in the archives of the Arthur B. Church – KMBC Radio Collection, housed at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, the station’s writers, actors, singers and musicians found light drama and good-natured comedy in scenarios involving country folk.

“KMBC was an exciting, innovative place to work,” said Chuck Haddix, curator at UMKC’s Marr Sound Archives. “Radio was still in its infancy, and they were making it up as they went along.”

KMBC distributed the programs across the Midwest on the Columbia Broadcasting System — the radio predecessor of CBS, the television network that carried “Hillbillies.”

“Creative young people swarmed the studios at KMBC and it was a three-ring circus,” Ruth Henning wrote some 60 years later in her manuscript, which she began writing while in her late 70s. “As far as I was concerned, it was the answer to everything.”

The station occupied a rooftop complex at the Pickwick Hotel at Ninth and McGee streets in downtown Kansas City.

Paul Henning started at the station as a singer, submitting several scenarios that showcased his tenor.

After a producer told him that such shows needed paying sponsors, Henning found one. The Associated Grocers of Kansas City bankrolled “The Musical Grocers,” which featured Henning as a singing grocery clerk.

Barth, and then Henning, soon left Kansas City for Chicago to contribute to programs such as “Fibber McGee and Molly” and “Don Winslow of the Navy.”

They married in 1939 and moved to Los Angeles. Over the ensuing 20 years, Paul Henning rose in the California radio — and then television — industries, writing for programs featuring entertainers Joe E. Brown, Eddie Cantor and Rudy Vallee as well as George Burns and Gracie Allen.

A portrait of a young Ruth Barth

As Ruth Henning tells it, her husband in 1959 had finished producing a situation comedy for actor Bob Cummings when a film studio executive who needed more television programming asked him whether he had any ideas.

Henning had several from his own recollections, including encounters with hill folk during Boy Scout trips to the Ozarks as well as the time he and Ruth went to Kansas City’s Orpheum Theater to see a production of “Tobacco Road,” with its impoverished Georgia tenant farmers.

He ultimately pitched a story derived from his ponderings over occasional newspaper stories describing isolated rural families that still lived without modern conveniences. The twist in his proposal was that spectacular good fortune had displaced the Clampetts from their lives without modern conveniences and dropped them in a world devoted to them.

Critics did not overlook the fact that “Hillbillies” debuted just one year after Newton Minow, Federal Communications Commission chairman, had delivered his “vast wasteland” speech in which he criticized the nation’s commercial broadcasters for not doing more to serve the public interest.

“If television is a vast wasteland, this show is Death Valley,” was one critique quoted by Ruth Henning.

Linda Henning said her father put on a brave face, but she had no doubt that such comments bothered him.

Ruth Henning unloads, in her book’s initial pages, on the television critics who disparaged her husband’s breakthrough program, “twining pasta on their forks and wiping virgin olive oil from their chins.”

And, when the opportunity presented itself, Paul Henning exacted revenge on Time magazine for its snide treatment of “Hillbillies.”

When it changed its tune, and wanted to interview Paul Henning when the show hit No. 1, his daughter recalled that “Daddy told the secretary to tell them to — how can I put this in a nice way? — shove it, basically.”

Paul Henning often served as the main writer on “Hillbillies” episodes, which showcased the Clampetts’ gift for frustrating those allegedly more sophisticated. His favorite characters were con men, whose plans to sell the Tower of London or the Brooklyn Bridge to this presumably stupid backwater family, always ended up backfiring.

In its earliest years “Hillbillies” delivered potent commentary, said Anthony Harkins, author of “Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon” and an associate history professor at Western Kentucky University.

The program’s scripts routinely depicted how the Clampett family often seemed oblivious to the fabulous wealth their new neighbors so clearly coveted.

“Money doesn’t liberate them in any way; they don’t change in any way, and they don’t want to,” Harkins said.

“Hillbillies” debuted amid the heightened tensions in the Midwest’s industrial centers, between factory workers and the Southern whites who were migrating north for those steel and automaking jobs.

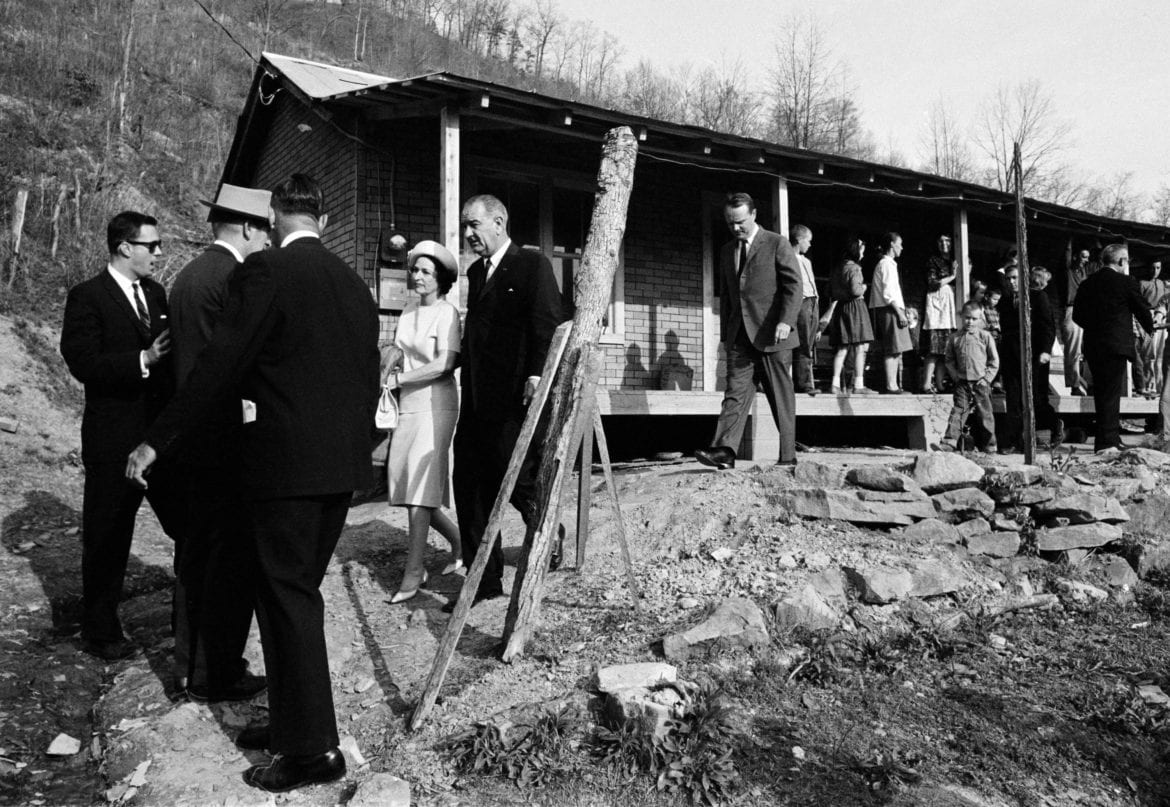

The show also aired against the backdrop of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, when the national media trailed the president to eastern Kentucky as he visited with families seeking economic stability in a region devoted to an increasingly automated coal industry.

Johnson made a point of visiting with white families, framing the scourge of want as ever-more urgent to those who may have assumed economic adversity was limited to blacks, Harkins said.

“I think it was a real shock to the American self-identity that we had large swaths of people living in poverty,” Harkins said.

In that context, programs like “Hillbillies” and “The Andy Griffith Show” served to comfort viewers, he said.

“These shows suggested that people living in the mountains and rural, small-town America were good folks who were choosing to live that life, so we didn’t really have to worry as much about the country’s economic system.”

It’s difficult to understand that “Hillbillies” once represented an apparent threat to the country’s culture, Harkins said.

Although he doubts that many millennials know “Hillbillies” today, they are likely to recognize the wilderness Jed Clampett emerged from.

“If you look at reality TV, there are probably 10 reality TV shows today that are set in the mountains, featuring men who are being men and not depending upon any kind of office culture or government handout.”

For “Petticoat Junction,” first broadcast in 1963, Paul Henning appropriated Ruth’s recollections of her grandparents’ small hotel in Eldon, in rural central Missouri.

The hotel stood within walking distance of a stop on the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. For “Petticoat Junction” the hotel became the Shady Rest, the train the Hooterville Cannonball.

That show also featured Uncle Joe, a character who often snoozed on the porch of the Shady Rest. “Happy Hollow,” a daily KMBC program that Henning both wrote for and acted in 40 years before, featured a similar character, Uncle Ezra Butternut, who lounged on the steps of the community’s general store.

In 1935, KMBC produced a nearly eight-minute film to promote its various radio shows to movie audiences in theaters around Kansas City. The clips below are portions of the film that included Ruth Barth in an episode of “Life on The Red Horse Ranch” and Paul Henning singing.

“Every time my father wrote a character, he wrote a biography of that person, so he would know that person well,” Linda Henning said. “His characters were so good because he made them real to himself.”

“Green Acres,” for which Henning served as executive producer, first aired in 1965.

“Hillbillies” still attracts an audience in context of a polarized political climate within which the definition of “hillbilly” continues to evolve.

The book “Hillbilly Elegy” sought to articulate contemporary Appalachian aspirations, prompting a variety of responses from both liberal and conservative pundits after it was published during the 2016 election season.

Paul Henning, meanwhile, always insisted his programs not be put in service of any political or religious agenda, Linda Henning said.

“He was adamant about that. There was one real skuzzy politician somewhere who was using the ‘Hillbillies’ theme in a horrible way. This man was a bigot.

“We tried to get ahold of him, but he lost the election and disappeared before we could find him.”

While the Henning home in Southern California included one living room wall stacked floor to ceiling with books devoted to the entertainment industry, none of those books concerned Henning.

That bothered Ruth Henning. Many entertainment industry veterans enjoyed steady employment because of Paul Henning, Ruth Henning believed.

“They lit candles to him in church,” she wrote.

As Ruth Henning writes, she confronted her husband about how any book about him would contain no random sex or violence. “How do you expect me to sell a book without any dirt to dish?” she asked him.

Paul Henning stood up and looked at his watch.

“‘I think if I start now I’ve just got time to go out and do something,’ he said. ‘What time is dinner?’”

Yet her book does indeed dish, in the inside-Hollywood way.

Raymond Bailey, who portrayed banker Milburn Drysdale on “Hillbillies,” had too much to drink on a flight to Kansas City where he was scheduled to make a celebrity appearance in Independence to promote a Noland Road bank — but sobered up sufficiently for showtime.

Producers cast young actress Sharon Tate to portray the blonde Billie Jo Bradley on “Petticoat Junction” — before someone discovered racy photos of her. The role then went to Jeannine Riley.

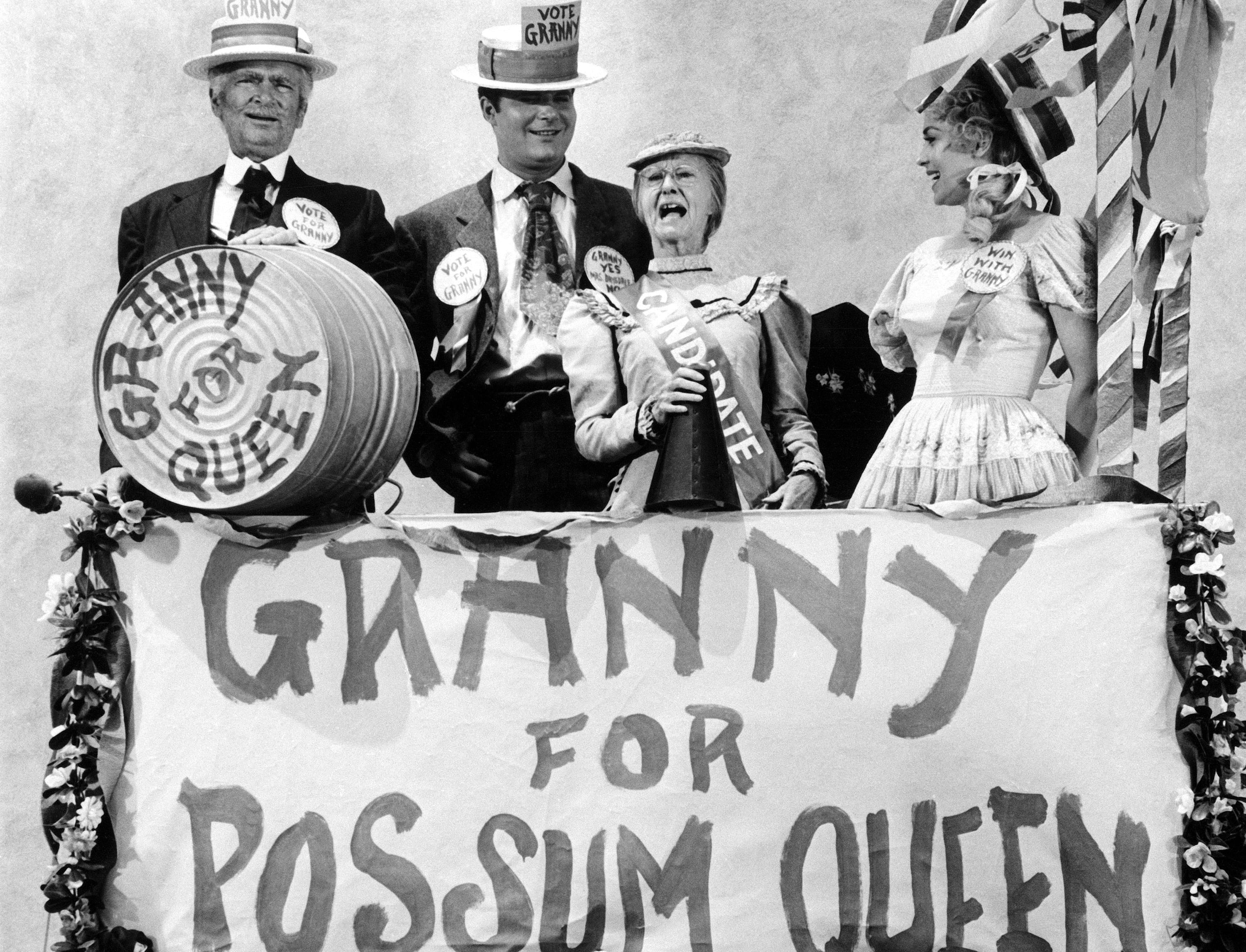

In a more poignant anecdote, Irene Ryan, whose career went back to 1920s vaudeville and who won the role of Granny on “Hillbillies” some 40 years later, once came to the Hennings’ home to thank them for her life-transforming opportunity.

“All my life I was small-time,” she told them, just before she went to New York to appear on Broadway. Not long after, she died from a brain tumor, and Paul Henning delivered the eulogy at her funeral.

Ruth Henning completed the manuscript in 1994. Although she never found a publisher, she apparently did forward a copy to Sue Gentry, a friend who was a longtime reporter, editor and columnist for the Examiner of Independence.

Gentry died in 2004 leaving no heirs.

Staff members of the Jackson County Historical Society later recovered the manuscript in one of the approximately two dozen boxes of papers Gentry donated to the society. Staff were convinced of its poignancy but had no way to get it into the public domain.

Opportunity to finally publish the manuscript arrived with the 2013 opening of the Woodneath branch of the Mid-Continent Public Library in the Shoal Creek district of Kansas City, North. The branch is the home of the Woodneath Story Center, a community publishing and storytelling initiative.

The center’s mission is to assist patrons in developing self-expression skills and writing personal and cultural histories. It also produces actual books.

The center’s Espresso Book Machine, a print-on-demand device that manufactures bound volumes, will produce paperback copies of “The First Beverly Hillbilly” to accompany an initial hardbound run published elsewhere.

The publication of the Ruth Henning manuscript demonstrates the unique role the Woodneath Story Center can serve, said Steve Potter, Mid-Continent Public Library director.

“Libraries can no longer be at the end of the production line when it comes to collecting stories,” Potter said.

Paul Henning continues to be contemporary. “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels,” a 1988 Steve Martin-Michael Caine remake of 1964 film “Bedtime Story,” co-written by Henning, opened as a musical on Broadway in 2005. A theatrical company producing the show toured England as recently as 2015.

A photo of actor Buddy Ebsen in character as Jed Clampett with the caption “What in Tarnation?” remains a popular social media meme.

Then there’s the restaurant chain whose name recalls Henning’s Hooterville.

Linda Henning said while she was uncertain of the term’s 1960s derivation, her father was not thinking of its more recent connotation.

“Daddy never would have used that if he had known what it would eventually signify today,” she said.

—To order a copy of “The First Beverly Hillbilly,” go to www.beverlyhillbilly.org.

—Brian Burnes is a freelance writer in Westwood, Kansas.

Archival materials used by permission of Linda Henning, Robin Blakely, the Jackson County Historical Society, the Missouri Valley Room, Kansas City Public Library; the University of Missouri-Kansas City Libraries, Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections and the Marr Sound Archives.