- Home | News & Issues |

- New Perspectives Emerge on Hyatt Regency Skywalks Collapse

New Perspectives Emerge on Hyatt Regency Skywalks Collapse Two New Books Take Differing Approaches to the Tragedy

Published May 25th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: The Skywalk Memorial Plaza is located in Hospital Hill Park at 22nd Street and Gillham Road. (Debra Skodack | Flatland)One day in 2015 R. Eli Paul, a Kansas City scholar with a long history of working with old papers, stared into a dark garage.

All he could say was wow.

What he saw, he later would write, resembled a “block-like mass of big boxes, plastic tubs, and rusty file cabinets” taking the space a Humvee could fill.

Historians sometimes write about the moment they, as if going forward holding a torch, come upon a previously undiscovered tomb of documents. The dusty papers Paul discovered — which would eventually fill 180 archival boxes — detailed the 1981 Hyatt Regency hotel skywalks collapse, which killed 114 people and injured more than 200 others.

The materials had been assembled by Kansas City attorney Robert Gordon, who as co-lead counsel for plaintiffs in a federal class action lawsuit, decades earlier had prepared to bring Hallmark Cards Inc., owner of the hotel, to court.

But a federal judge in early 1983 announced a settlement in the class action, and the trial Gordon had been preparing for never began. Deflated, the lawyer began what Paul described as the ”dismal process” of boxing up his case files and moving them to off-site storage. Gordon soon resolved to write the book he believed needed to be published, presenting a counter-narrative to what he felt had become an accepted version of events.

That never happened, either.

But the 180 boxes proved crucial to the recent publication of two books that today represent contributions to the community memory of the worst thing to ever happen in Kansas City.

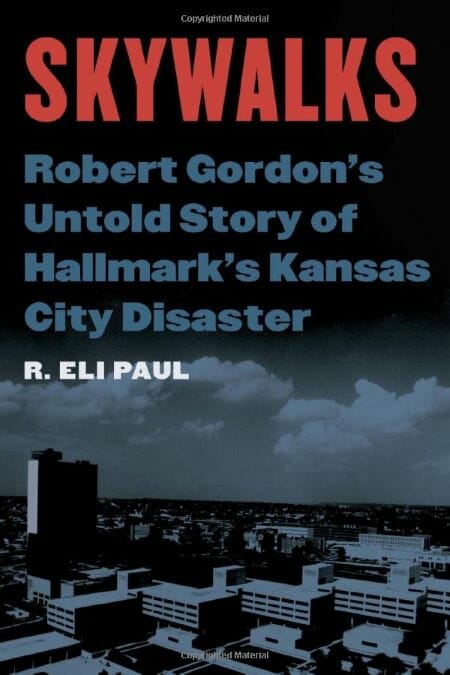

“Skywalks: Robert Gordon’s Untold Story of Hallmark’s Kansas City Disaster,” written by Paul and published this spring, unpacks the lawyer’s efforts to seek what he considered justice for his clients and then, failing that, author a book detailing his case and present it to the court of public opinion.

That included, Paul said recently, Gordon’s belief that Hallmark, “which as the owner made all of the important decisions regarding schedule and budget, should have realized that its hotel was unsafe.”

Gordon had died of colon cancer in 2008 and 10 years later Paul — retired director of Missouri Valley Special Collections, the Kansas City Public Library’s local history archive — resolved to write the story he would find in Gordon’s papers, donated to the library by Gordon’s family and including 22 chapters of the lawyer’s surviving manuscript.

As a scholar of the 19th century American West, Paul knew his way around untold stories. In 1997 he had served as editor of “The Autobiography of Red Cloud, War Leader of the Oglalas,” an “as-told-to” account which had sat for decades at the Nebraska State Historical Society.

“All it took was the courage to venture forth into the 20th century, unknown territory for me,” Paul said recently.

He also decided to focus almost entirely on Gordon and the story his papers told.

“This is Gordon’s view of the world,” he added. “I’ve tried to be very clear about differentiating between what Gordon stated, believed, conjectured, concluded, deduced and assumed, and what I ultimately conclude as the author.

“It’s his story.”

Another researcher, meanwhile, was circling the same story.

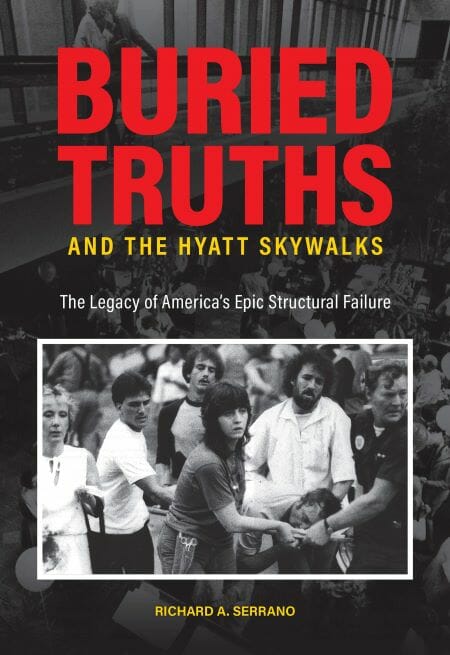

In 2021, upon the disaster’s 40th anniversary, Richard A. Serrano, a former Kansas City Times reporter who had helped cover the post-collapse investigations and litigation, published “Buried Truths and the Hyatt Skywalks: The Legacy of America’s Epic Structural Failure.”

That book, like Paul’s, describes Gordon’s efforts, frustrations and his ultimate personal decline following the 1993 cancellation of his book contract.

When Gordon’s Jaguar didn’t start one day, Serrano wrote, he simply let it sit — not in his garage but out on the driveway.

Near the end, Gordon often wouldn’t get out of bed.

His legal career ended, as did his marriage.

But Serrano widened his focus beyond Gordon. His book not only described how the disaster affected survivors but also how the collapse soon influenced policy and practices within the professional communities of engineers, architects, first responders and others.

“For me, the work morphed into a never-ending trip home again,” said Serrano, a Kansas City native who worked for the Times from 1972 through 1987.

After an initial trip in 2018 to the National Archives to examine materials generated by a federal standards bureau’s investigation into the disaster’s causes, Serrano drove from his suburban Washington home to Missouri.

There his stops included the Jackson County Courthouse in downtown Kansas City, where he retrieved papers from the many Hyatt-related lawsuits filed in state court.

In 1979 and 1980, he covered the courthouse for the Times.

“So, just walking back through the old Jackson County Courthouse doors immediately got my juices flowing,” he said, adding that “there was still a lot to be told about the Hyatt disaster, especially since there never was a trial and the public never fully learned what went wrong at that hotel.

“That is what I wanted to tell.”

The ‘Gordon Thesis’

Just after 7 p.m. on July 17, 1981, two elevated walkways known as “skywalks” fell to the Hyatt’s atrium below, where hundreds of guests had been enjoying a “Tea Dance,” a popular Friday evening promotion.

Seven months later National Bureau of Standards officials announced the findings of their investigation into the collapse.

They explained not only how the walkways’ original design had not met Kansas City building code requirements, but also how a later design change had “further aggravated an already critical situation.”

In an earlier design, the bureau reported, both the fourth- and second-floor walkways were to be suspended from a set of steel support rods.

As ultimately constructed, however, one set of rods suspended the upper walkway from the ceiling, while a separate set suspended the lower walkway from the upper one.

This change effectively doubled the stress on critical connections on the upper walkway, the bureau reported.

As a result, one connection — the center rod on the east side of the upper skywalk — likely failed first, sending both walkways crashing to the crowded hotel lobby below.

It was, the bureau said, “the most devastating structural collapse ever to take place in the United States.”

Gordon added those findings to the evidence he intended to present in court against defendant Hallmark Cards, developer of the hotel.

But in January 1983, U.S. District Court Judge Scott O. Wright announced that a proposed $10 million settlement had been reached. It included $6.5 million that Hallmark would donate to several area charities.

It meant there would be no trial, and Gordon would not present his case in court.

Three years later a Missouri state board revoked the licenses of two structural engineers employed on the project.

For many, Gordon believed, blame now had been placed at the feet of those two individuals, and the story ended there.

But that version of events, Gordon felt, left out a lot.

Gordon believed that an October 1979 collapse of a part of the hotel’s atrium roof had been downplayed dramatically by Hallmark. A company spokesperson initially had said that a single 16-foot steel beam had fallen.

It had been worse than that.

“Four 18-foot steel beams had come raging down, one weighing 12 tons,” Serrano would write. “Concrete smashed apart too, breaking a 200-foot hole in the terrace restaurant overlooking the atrium.”

Since the failure had occurred at about 6 a.m. on a Sunday, no workers were on site, so nobody had been injured.

Gordon further insisted the atrium collapse represented what Paul, in a presentation at the Central Library this spring, called the “reddest of red flags.” The project, Gordon believed, should have been paused.

But, in what became known as “Gordon’s thesis,” the lawyer believed Hallmark executives chose to push the project forward, prompted in part by the approximately 400,000 hotel reservations already booked.

This, according to Paul, persuaded Gordon that the hotel’s builders had sufficient motivation for cutting corners.

As Paul wrote in his book, Gordon believed that hotel “received a clear warning from the 1979 atrium roof collapse but did not heed that warning.

“The failure to deal correctly with the first collapse led to the second in 1981.”

Further, Paul said, Gordon believed the 1979 roof collapse “demanded someone, anyone, to speak up and ask whether other areas of the construction site were at risk and to halt work until a thorough, comprehensive inspection was made.”

Gordon also believed Hallmark declined to accept that a direct relationship existed between the two collapses.

“If so, it would have meant that the blame for the Hyatt disaster expanded from one of a single instance of faulty engineering to a toxic environment of bad project management,” Paul said, adding how “that meant shifting the blame from only a couple of structural engineers to many others, including the owner who set the schedule, wrote the checks, and supervised them all.”

But the class action lawsuit had been settled, and no jury would vet Gordon’s thesis.

The insurers of the Hyatt defendants ultimately paid out about $150 million to settle the case and compensate the victims, Paul said.

So Gordon then focused on making his case in hardcover.

He believed a “tell-all” expose could find an audience and the New York publishing industry agreed — at first. By 1985 Gordon was working with an agent and collaborator.

The first title proposed by Gordon signaled his regard for Hallmark. It was to be called “When They Didn’t Care Enough,” an unsubtle jab at a familiar Hallmark company slogan, “When You Care Enough to Send the Very Best.”

A later title was “House of Cards,” and Simon & Schuster later circulated a promotional piece announcing the pending book, which would tell the “shocking truth” of “the whole sordid tale of pride, greed and negligence…”

But it never appeared.

One problem, as documented by Paul, was how Gordon didn’t enjoy collaboration and soon alienated and exasperated several writers and editors. However sympathetic they might have been to the “Gordon thesis,” they found the lawyer himself impossible to please.

One writer who turned five Gordon chapters into two later discovered all his excised portions restored.

The writer, Paul said, “felt like he was writing in the sand on a beach.”

In this way, Gordon’s manuscript grew heavy with legal jargon and attitude.

“For the book to work,” Paul wrote, “this key insider and self-made expert needed to come across as a measured advocate, not as a snarky over-the-top, pitiful obsessive. Actually the former was to be found there on the page, and his collaborators tried to bring out the storyteller and not the litigator but never succeeded in preventing his darker side from haunting the manuscript.”

By the time Simon & Schuster dropped his book contract in 1993, Gordon’s surviving manuscript included 854 pages of narrative that were, Paul said recently, “350 more than his New York editors wanted.”

And that didn’t include Gordon’s lengthy footnotes.

For his book, Paul chose to focus on Gordon and not seek out the contemporary recollections of others.

“That might appear all narrow, but I approached the subject as a historian, not as a journalist,” Paul said.

“I worked with and depended on the documentary record produced at the time. I relied on the Gordon papers, a rich, untapped documentation of the time, as opposed to the added effort of soliciting modern opinions from people who have had 40 years to think about it and massage their response.

“That helped keep me — and I hope, the reader — grounded in the 1980s. As a historian, I’m trying to bring the past to life, and Kansas City in that distant decade is a faraway time and foreign country to us now.”

Arriving Unannounced

Serrano, meanwhile, tracked down 240 sources and, as he learned, the individual legacies of the skywalks collapse survivors’ legacies proved varied and idiosyncratic.

One survivor stayed inside every July 17.

Another lit a candle and had a drink.

Still another, who suffered a broken back in the collapse, bought a new mattress every three years to soften the ache.

Evelyn Gubar, whose husband Joe died while standing in line for drinks, told Serrano she continued to see him in her sleep, almost 40 years after the collapse.

“I dreamed of him just last week,” she said. “I see him in my dreams coming towards me and then it’s all over.

“I’m always left waiting for him.”

A 19-year-old Hyatt parking attendant who ran to the hotel lobby to help later received a $3,000 settlement and moved to New York. There, following the terrorist attacks of 2001, she sometimes found herself growing nervous whenever a subway train, stopped at a station, paused just a little bit longer than usual.

Other responders unable to avoid seeing the worst later noticed their responses to otherwise everyday stimuli.

A law school student who had married her husband, a Hyatt management trainee, just three weeks before the collapse — and who on July 17 joined her husband in banging on Hyatt hotel doors, instructing guests to leave — told Serrano she still could not consider eating any meat or poultry still attached to a bone.

In search of such deeply personal details, Serrano often arrived unannounced.

“I would go to neighborhoods and cold knock on doors,” Serrano said recently.

“I always was invited inside.”

If no one was home, Serrano would leave a note with his number in a mailbox. Sources routinely called him back.

“I will tell you this,” he said. “Every single time they all broke down in tears. Every one of them. Not just the victims but also firemen, police, paramedics, doctors, construction volunteers, lawyers, and on and on.”

After a while, Serrano said, he began packing folded Kleenex in his coat pocket.

Most of the individual Hyatt-related lawsuits were settled within about 18 months of the collapse and some of Serrano’s sources told him they regretted their decisions.

“It really was not a good deal,” Gubar told Serrano.

“But I didn’t care because I didn’t want to live then.”

And yet not every legacy of the skywalks collapse proved negative.

The Paola, Kansas, family of Jeff Durham, who was pinned underneath a skywalk and only was freed following the amputation of a leg with a chainsaw, took the settlement money and built an affordable housing development. It includes a community park at the intersection of Jeff Circle and Durham Drive.

Many of the nation’s engineering schools added courses on morals and accountability, Serrano learned.

The American Society of Civil Engineers, in hopes of avoiding confusion in future construction crises, approved a new “Manual of Professional Practice” mandating that a structural engineer serve as the ultimate accountable professional at any job site.

Never Moving On

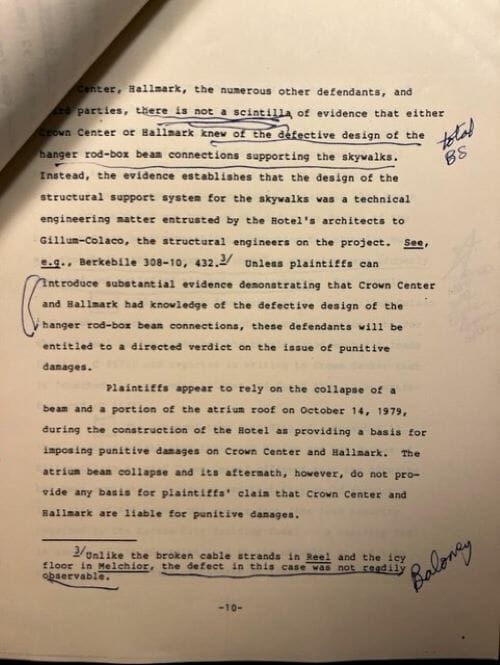

Gordon’s legal adversaries during the post-collapse litigation, Paul said, described him with adjectives ranging from “dogged” to “reckless,” “offensive,” “irrational” and, finally, “obsessive.”

While Gordon’s papers have yet to be formally cataloged and processed by Missouri Valley Special Collections, the lawyer’s materials are now open to researchers who request appointments in advance of their visits.

It’s not difficult to find in the material hints of the pitch at which Gordon operated.

In the margins of one pre-trial memorandum filed in federal court on behalf of Hallmark Cards, Gordon scribbled his own opinion of various assertions.

“Total BS,” one note reads.

“Baloney,” reads another.

When an investigation directed by Jackson County Prosecuting Attorney Albert Riederer into any possible criminal negligence in the skywalks’ design or construction ended in late 1983 because of what Riederer called “insufficient evidence,” Gordon wrote several angry letters to him, demanding he reopen the inquiry.

Disagreements with representatives of The Kansas City Star/Times prompted still other letters.

“Angry? You bet I am,” Serrano quotes one letter’s opening salvo.

Serrano, who served on a four-reporter Star/Times team assigned to the Hyatt story, often found himself on the receiving end of Gordon’s frustrations.

The newspapers, which were jointly owned but whose staffs competed, published many exclusives detailing the hotel’s design and construction. The Star/Times would receive a Pulitzer Prize the following year for “coverage of the Hyatt Regency Hotel disaster and identification of its causes.”

One Serrano story, appearing on the front page of the morning Times two weeks after the collapse, told how examination of daily mileage logs revealed Kansas City building inspectors had spent a total of 18 hours and 20 minutes in 37 on-site visits during the hotel’s 28-month construction.

That meant an average of less than nine minutes a week had been devoted to inspecting the building of the $50 million, 40-story structure.

Sometimes, the records showed, weeks went by with no visits at all. In October 1979, the month much of the atrium roof had fallen, records documented no inspector visits.

Despite such stories, Gordon, according to Paul, sometimes believed the newspapers pulled punches in deference to Hallmark, especially following the October 1982 death of company founder Joyce Hall.

That’s incorrect, said Serrano, who remembered one Hyatt story being held briefly after Hall’s death, but being published soon after.

Hallmark, he added, did not bear total responsibility for the collapse.

“Yes, Hallmark built and owned the hotel building,” Serrano said. “But they did not make the skywalk design change; they did not encourage the city inspectors to look the other way.”

Gordon, Serrano believed, in his efforts to represent his plaintiffs, lost needed perspective.

“I showed in my book that he was obsessed with blaming Hallmark and the Hall family for the Hyatt disaster and that his obsession eventually led to his later troubles, especially after his hoped-for book deal fell through,” he said.

“A good man, an able man, Gordon in hindsight seems misguided in believing Hallmark alone was responsible.”

After his book contract was canceled, according to Paul, Gordon would never practice law again.

Over time he began staying in bed and seemed to slip into what his family believed to be a depression that contributed to his decline.

He didn’t seek treatment for it.

As late as 2000, Paul wrote, Gordon sent his manuscript to one more editor, whose opinion merely mirrored those of other editors years before. The sheer amount of legal detail, the editor said, was “mind-numbing,” and the manuscript needed to be cut to 500 pages.

Gordon’s marriage had ended three years before.

“He would not move on,” Gordon’s former wife, Josie, later told Paul. “So, I moved on.”

What History Needs

More than 40 years after the disaster, Paul believes his book should not be the last word.

After Paul’s recent Central Library presentation, Bob Berkebile, chief Hyatt project architect, stood and said he considered much of what he understood to be “Gordon’s thesis,” was, in fact, “not consistent with the truth.

“Don Hall was not pressing to make this faster and cheaper, nor was Hallmark,” Berkebile added, calling the company “one of the most conservative, caring clients I’ve ever worked for.”

Further, Berkebile said, rather than ignoring red flags and pushing forward in a reckless way following the 1979 atrium roof collapse, project executives did not “accelerate the work and look for cuts and say, ‘We are not going to pay for this,’ they and we shut the project down entirely and asked our structural engineer to return.”

Two other engineers were brought in, Berkebile said, one of them a failure analysis forensics expert.

“And with no construction underway they spent two weeks following our directive, which Don Hall supported and repeated, and that was to examine every connection — steel-to-steel and steel-to-concrete — and give us a report on their integrity.”

It’s clear Gordon brought passion to his task, Berkebile said.

“But I think that he was on a path that was at least inconsistent with my experience, and I would argue the experience of the owner and others who invested a lot of their lives in this community facility.”

In response, Paul said he considered Berkebile’s remarks a welcome addition to what could be a continuing dialogue about the collapse, and that the architect should consider publishing his own book, preserving his perspective of the collapse.

“History needs this,” Paul told Berkebile. “We haven’t talked about this subject, probably, enough.”

Today Paul believes there is still a chance a future team of editors could make Gordon’s surviving manuscript viable.

It’s also possible, he added, that despite the 180 boxes of Gordon materials now on file at the Kansas City Public Library, more documents may still be held privately and could be made public in the future.

Perhaps, he said, such papers remain filed in the law offices of firms which represented both Hyatt plaintiffs and defendants.

“I’m an optimistic historian,” Paul said, “and all I can do is hope.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes served as a Kansas City Star reporter from 1978 through 2016.

More on Flatland

Finding A ‘Peaceful Place’ in the Long Shadow of the Hyatt Skywalk Tragedy The Skywalk Memorial Foundation, which helped create a memorial near the site of the Hyatt skywalk collapse, is winding down its affairs following the 40th anniversary of the disaster that killed 114 people in 1981.

Like what you are reading?

Discover more unheard stories about Kansas City, every Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!

Check your inbox, you should see something from us.

Ready to read next

I was waiting for my dinner date to pick me up on Saturday night when I learned he would not be coming.

He was in line at the bar when the skywalks collapsed and was killed instantly. His name was Sam Cottingham. I had been invited to join the group for the Tea Dance!

Fate works in strange ways.

A night I will never forget. Tragic.