New Documentary Highlights Legal Immigrant Plight Backlogs Make 'Green Cards' Nearly Impossible for Immigrants from India

Published February 23rd, 2023 at 1:00 PM

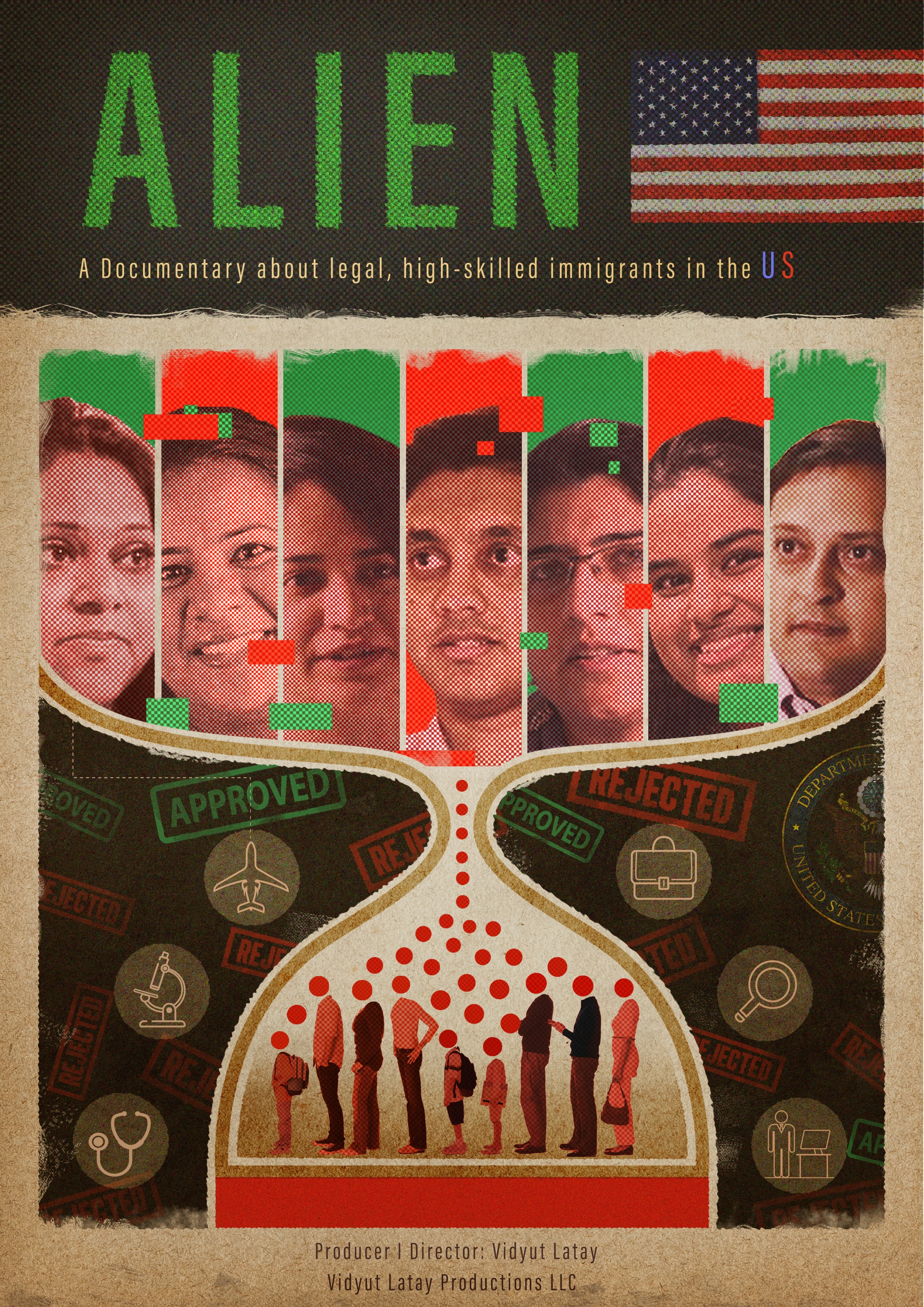

Above image credit: "Alien" is a documentary about legal, high-skilled immigrants. (Screenshot | "Alien" Trailer)Six years have passed since the initial grief and anguish of Sunayana Dumala consumed local and international headlines.

The first part of her story, a hate crime that took the life of her husband, will ring familiar to many in Kansas City.

She is the widow of Srinivas Kuchibhotla.

Her beloved “Srinu,” an engineer at Garmin, was shot and killed by a man who targeted him and his friend, both immigrants from India.

The two men were merely sitting together that February 2017 evening, having a beer after work as University of Kansas basketball played on the flatscreens at Austin’s Bar & Grill in Olathe.

The gunman, now serving three consecutive life sentences, poked Kuchibhotla in the chest and shouted, “Get out of my country!”

Adam W. Purinton had previously told other patrons that he thought the engineers were “terrorists.”

His ignorance highlighted anti-immigrant sentiment, gun violence and the bravery of another local man who also was shot trying to intervene. Kuchibhotla’s friend was also shot but survived.

Less known, is that “the incident,” as Dumala refers to that night, also underscored inequities in the U.S. immigration system.

“I can’t talk about my story without talking about immigration,” Dumala said.

The reason is that her legal status was tied to her husband’s employment at Garmin. Without him, she was susceptible to deportation.

This aspect of Dumala’s life is featured in a documentary premiering March 9 at Glenwood Arts Theatre, 3707 W. 95th St. in Overland Park.

Watch:

“Alien” by award-winning director Vidyut Latay, explores the nearly 100-year wait that many highly-skilled immigrants face to gain legal permanent status.

In layman’s terms, what they’re approved for, but now must wait more than a lifetime to gain, is a “green card.” It’s the last step before an immigrant can become a U.S. citizen, a process that takes another three to five years.

Dumala’s hope for the film’s screening and a panel discussion following, is to counter disinformation.

“We are only trying to expose people to what immigrants go through,” said Dumala, who has testified in Congress multiple times, advocating for reforms.

She likens her situation after the murder to dual victimization.

First, by the gunman. And then by decades-old caps on the number of green cards allowed per country for families brought to the U.S. by their expertise in technology, medicine, science and other important skills through an H-1B visa.

“Foreign workers find themselves trapped in a system that keeps them from being able to fully realize their dreams,” said Kansas City-based immigration attorney Rekha Sharma-Crawford. “For many, the dream has long turned into a nightmare plagued with stress and uncertainty.”

The rules, which only Congress can address, have created a nearly impossible situation for people from India, and to a lesser extent, people from China.

Sharma-Crawford, Dumala and Latay will take part in a panel discussion following the screening, which begins at 6:15 p.m.

The event is free. But people are asked to register to attend the screening and panel, “Fairness & Belonging: Discussing the State of the American Immigration System.”

The Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce, through its Welcoming KC plan, is also involved in the evening.

Native-born North Americans tend to see issues of immigration in segmented, sometimes conflicting snippets.

But a heavy focus on undocumented immigrants and the U.S.-Mexico border region dominates, in media and political circles. This leaves far less attention to the issues concerning immigrants who arrive legally through the sponsorship of the businesses that employ them.

“Year after year, administration after administration, Congress after Congress, no one seems to have any interest in finding workable solutions,” said Sharma-Crawford. “Can you imagine an Indian national who is in the tech industry is looking at roughly a 90-year wait for a green card. How can anyone think that is reasonable?”

Congressional inaction and the hate crime that took her husband’s life, launched a sense of activism in Dumala. She founded Forever Welcome, a nonprofit which seeks to generate empathy and understanding for immigrants to the U.S.

The screening is being held on what should have been her husband’s 39th birthday.

“This documentary is not just for Indians,” Dumala said. “It’s to raise awareness that not every immigrant story is the same.”

It took advocacy from two U.S. Congressmen, more than four years after the murder and ultimately an unexpected twist of fate of the pandemic to rectify her situation.

Dumala, who relocated to Florida last year, is now a lawful permanent resident. She plans on becoming a U.S. citizen in time to vote in the next presidential election.

Another estimated 1.4 million highly-skilled immigrants legally working in the U.S. haven’t been as lucky. They continue to wait.

Immigrants as ‘Aliens’

The film’s title, “Alien” comes from a sign that shocked the director when she arrived at a San Francisco airport and needed to pass through U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

There was the line for U.S. citizens reentering the country, and one for people like her, an immigrant from India.

Her line was titled, “Aliens.”

“I just froze,” Latay said. “I literally did. I was devastated. This was my first international travel from outside India.”

Her India-born husband, who had been hired on an H-1B to work in Silicon Valley, ushered her through the process.

The word “alien” is used often in immigration law. But it’s long been criticized for a double meaning, seeming to label immigrants as extraterrestrial beings.

The experience was only a small part of what Latay felt later, as a “dependent” on her husband’s work visa, unable to work herself in the U.S., despite having come from a flourishing career in media in her native land.

“It’s almost like that status of being a dependent, or being a temporary worker who is stuck in the green card backlog, overpowers every scope, every aspect of your life,” she said.

It’s a paradox that she explores in the film.

People can become tethered to their employers, because the job ensures their legality, with no room to shift until they can adjust to permanent legal status, which can mean a decades long wait.

Their families are also somewhat held, with possible gaps in legal status as attempts are made to shift from say an international student visa, to a work-related one.

Privileges such as the ability to have a driver’s license come into play. And sometimes, people aren’t allowed to leave the country, finding it impossible to return to their homelands to visit a sick relative.

Latay felt compelled to explain: “Why is the immigration system broken and how does it really impact families and individuals.”

To her, it seems like a disconnect when the U.S. is known to be a land that was largely built by immigrants.

“The reasons could be multiple,” Latay said. “But I do feel that there is no political will to fix the high-skilled immigration issues.”

In addition to Dumala, the film also features the plight of a pre-med student who faced what’s termed “self deportation” because she aged out, reaching 21 before her H-1B parents could receive their green cards.

Such college students don’t qualify for the temporary fixes that have been achieved for others, such as the DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. That’s an Obama-era program linked to the plight of the so-called DREAMERS, people who were brought to the country without authorization by their parents when they were young.

The children of parents on work-related visas are considered dependents and have legal status, but only if they are under 21.

The documentary also highlights the story of an oncologist, a cancer scientist, a psychologist and a couple who waited nearly 20 years for their green cards before eventually giving up and moving to Canada.

Green Cards Haven’t Always Been Green

Green cards initially were green. Then they became a salmon color, yellow, a purple-blue, but the name stuck in common usage. The design of the cards change with regular updates.

The majority that are available each year, 260,000, are allotted for immigrants who are joining close relatives like a parent or spouse– who already have a permanent status in the U.S.

There are backlogs there as well, simply based on demand.

For people in the country on work-related visas, there are 140,000 green cards available annually. But there is a 7% cap per country.

People are given priority dates once they are approved. And their wait begins.

An uptick in recent years of hiring people from India has meant that their line for gaining a green card continues to expand, said Sharvari (Shev) Dalal-Dheini, director of government relations with the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

“A Western European person will get their green card in maybe like two years,” Dalal-Dheini said. “And an Indian could wait decades, multiple decades.”

Employers must work with the U.S. Department of Labor to hire an immigrant on a specialty visa, like an H-1B. They must prove that there are no qualified and available U.S.-born citizens who can take the job.

It’s part of the protective clauses written into the law.

But increasingly, economists point to low unemployment rates and the baby boomer population retiring from the workforce as related issues.

There simply are not enough workers numerically in the U.S., which is causing some to argue that hiring more immigrants is imperative to a sound economy.

“It’s just not reflective of what our world is today,” said Dalal-Dheini. “And what the mobility is like–how easy it is for people to travel and move and want to work, and how global our workforce is now.”

There have been multiple efforts in last dozen years to pass legislation addressing the caps and backlogs. One holdup has been a fear that lifting caps will aid one set of immigrants, while extending the waits for others.

The proposed bills have gone by differing names. There was the EAGLE Act, (Equal Access to Green Cards for Legal Employment) and the Fairness For High-Skilled Immigrants Act. Neither passed into law.

Aman Kapoor, founder of the advocacy group Immigration Voice, believes that too many people benefit from the status quo.

Immigration attorneys profit from the fees they charge businesses to manage the complicated process of hiring under work visas, he said.

Democrats and Republicans accept political donations from high tech and other firms heavily dependent on the high-skilled immigrant labor. Those businesses want the immigrants to remain beholden to them, unable to leave for another job, or possibly start a competing firm.

Too often, Kapoor said, the human rights of the Indian immigrants themselves aren’t considered.

“The issue is that deliberately, the system is discriminatory,” Kapoor said.

Others said it is too early in the current legislative session to predict if any bills will gain traction.

After 15 years in the U.S., Dumala received her green card in August of 2021 due to shutdowns of foreign embassies during COVID. Those cards, meant for family reunification, couldn’t be processed during the year they were available, so they were shifted to those waiting through the employment side of immigration.

She believes significant reform can be achieved if Congress works to pass laws addressing specific issues for different categories of immigrants.

The needs of South Asians caught in decades long waits for a green card are just one area ripe for reform, she said.

Too often, politicians believe only a massive comprehensive fix will do.

“By taking this approach, Congress isn’t making anyone happy,” Dumala said. “They’re not fulfilling any of the people’s hardships and are putting everybody in limbo.”

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS.