Missouri Offers ‘A Phenomenal Place to Homeschool’ COVID Prompted More People to Homeschool; KC is Here to Support It

Published December 13th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: McGhee's children do both online and in-person homeschooling. Here, her youngest works on a typing lesson. (Contributed)Few people can say they’re grateful for the COVID-19 pandemic.

But without the lockdown and change of pace, Tania Edwards would never have considered homeschooling her children.

She and her husband both worked full-time, and their two daughters went to a private school in Raytown, Missouri.

During the early months of the pandemic, Edwards found herself working from home while her daughters took their classes remotely.

Then, things started to open up and Edwards went back to her office as an administrator at Calvary University.

“My kids…got used to something that maybe they missed,” Edwards recalled. “I hate to use the word guilty, but that’s the best word I could think of at the time.”

Edwards and her husband crunched the numbers and realized most of her salary went to the kids’ private school tuition and gas to drive to and from her office. Financially, the family could support homeschooling.

“I could be at home,” Edwards remembered thinking. “And that’s where the journey happened. We said we’ll try it out for a year, and of course we need to be modest, but at least I’d be at home.”

Two years later and the family is still schooling from home.

“I’m so glad the COVID pandemic happened because it slowed you down,” Edwards said. “We had enough time to think about whatever we wanted to think about, and (homeschooling) was one that was a complete surprise.”

Edwards was one of the many families who reached this decision in the past two years.

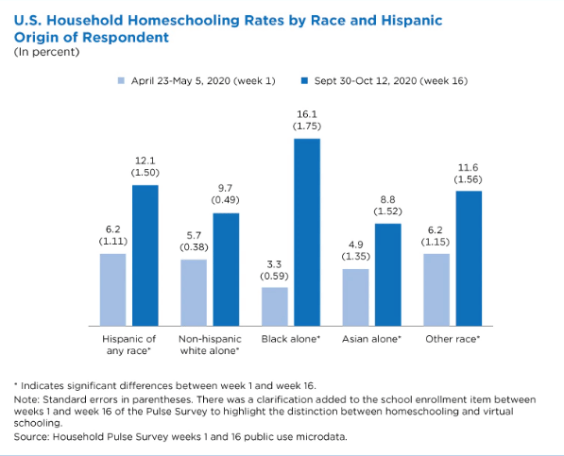

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, the percentage of U.S. households that homeschooled more than doubled from the 2019-2020 school year to the 2020-2021 school year.

Missouri saw a similar increase with 5.9% of the population homeschooling in 2019-2020 and 10.9% in 2020-2021.

A report by the National Home Education Research Institute estimates that the number of homeschooling households has decreased since the 2020-2021 school year, but remains higher than pre-pandemic years by significant levels. If such gains are sustained over time, homeschool could emerge as a genuine alternative that may affect traditional schools.

The Edwards family realized they could school alternatively – and that the Kansas City homeschooling community was full of opportunities.

The Kansas City region offers a wide variety of activities and support networks for homeschooling families. The goal of most in the network is to make homeschooling a reality for any family who wants to embark on the journey.

Homeschooling in Missouri

Danielle Dent-Breen is the Families for Home Education (FHE) director for the Kansas City region. She also has two children, one 15 and the other 12, whom she has homeschooled since they reached schooling age.

“Kansas City’s a phenomenal place to homeschool,” she said. “There are so many opportunities for kids. We have sports leagues, we have co-ops, we have so many things going on that you have to be a wise steward of your time.”

FHE exists to provide resources to homeschooling families, to help foster community connections and to explain the Missouri homeschool laws.

“It can be isolating if you don’t make connections,” she said. “That first year that you homeschool can be intimidating … so one of the things that we try to do is really help families make those connections in the area.”

In Missouri, the basic rules are to offer 1,000 hours of instruction (per year) during a child’s compulsory education ages from 7 to 17. Six hundred of these hours have to be in primary subjects (reading, English, math, science and social studies), and two-thirds of those core subject hours must be taught at the primary location, in most instances, the family home.

Dent-Breen said parents are also obligated to make note of these hours and keep examples of the child’s work in a portfolio. These portfolios can only be seen in the instance of a child neglect case, and are not required to be submitted to the state under normal instances.

Parents will often try to recreate the classroom setting when they start homeschooling, because it’s what they know. Dent-Breen said one of the benefits of homeschooling is that it doesn’t have to look like a chalkboard and desks.

“I had little school desks and had a little classroom that he (her son) ruined in a heartbeat, because that was not him,” Dent-Breen said of her early homeschooling journey.

Instead, she had her son bounce on a trampoline while he did his math, or dribble a ball to learn his spelling. At home, she was able to cater to his learning style in a way that wouldn’t work in a full classroom.

“That’s how I fell into homeschooling. I thought, this little wild thing is going to be eaten alive in a classroom with 30 kids,” Dent-Breen said. “I love him and he makes me crazy – I can’t imagine having him in the classroom.”

‘It Takes a Village’

Homeschooling is inherently personalized based on each family, and each child.

Dent-Breen said today folks from all walks of life are choosing to homeschool in Kansas City.

The most common families are single-income households where the mom stays home to teach. But sometimes, it’s a dad who stays at home and is the primary teacher, and some families have two working parents who fit lessons in after work and on the weekends.

“We’re seeing such an explosion of people of all ideological persuasions, all ethnic groups – it’s really been very exciting to see that,” Dent-Breen said.

Erin McGhee, Dent-Breen’s assistant director, said there are many reasons why folks are choosing to homeschool.

For some, it’s because their children are struggling with learning or social disabilities. Others see their children bored in a classroom that doesn’t move quickly enough. And some disagree with school politics, or have children with severe food allergies and health concerns who feel safer at home.

In the past, McGhee said homeschooling was for people who wanted to create their own idea of school. Today, she said people are seeking an escape from something they see as not working.

“Some of those people have fled to this new land of homeschooling and loved it, and have found great success with it,” McGhee said.

To McGhee, if someone wants to homeschool, there’s a way to make it happen.

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way,” McGhee said. “That might come at maybe moving into a smaller house, or a different neighborhood, or a different part of the country where there’s more things accessible.”

Homeschooling can look like a lot of things, so McGhee said parents can get creative to make it work if it’s something they really want to do.

Emily Dingley has been homeschooling her seven children for the past 12 years.

She started her homeschooling journey in California, where, at the time, the rules were fairly strict. Dingley had to get approval from the school district her children would have been enrolled in, then meet with an accredited teacher to go over the curriculum she planned to teach. On top of that, she had to log her children’s attendance and activities each week in an online portal.

“I feel like that actually deters a lot of families from homeschool,” Dingley said. “It’s this mountain of paperwork and if I don’t complete every little teeny tiny thing to the umpteenth degree… You feel like you’re gonna be in big, big trouble.”

Since starting to homeschool, the Dingleys have moved from California to Utah and finally to their current home in Peculiar, Missouri. Dingley said even in the smaller rural town she lives in there are plenty of homeschooling resources and community.

Because Missouri requires 400 hours of instruction each year to take place in the child’s home, co-ops can’t provide all of the teachable hours. But, it can help some parents get tasks done during the day if it’s a drop-off style co-op.

Dingley said co-ops are also great for extracurricular activities and specialized classes. Additionally, they allow parents to meet one another, swap curriculums, share their experiences and generally offer some support.

“I think a lot of families think that it’s this really unattainable thing financially,” she said. “It’s not, and it doesn’t have to be.”

Dingley said curriculum and activities can be found on free websites, at public libraries and from other parents.

Homeschool Regulations

Investopedia estimated in 2022 that the average annual cost to homeschool per student was between $700 and $1,800. The same article lists similar spending on supplies and extras for children in public school, and noted the average family spends upwards of $12,000 in private school tuition per child per year.

Even the most enthusiastic homeschooler is quick to clarify one point – it isn’t for every family.

“I don’t want it to come across like, ‘Oh my gosh, homeschooling is the only way,’ ” Dingley said. “I completely disagree. Every family has different dynamics going on, and some people are not able to do that, or they just simply don’t want to and that’s totally fine.”

The aspiration is that folks know the option to homeschool exists.

“My hope is that if your choice or your calling is to homeschool, don’t let your finances hold you back,” Dingley said.

Her family has made sacrifices because homeschooling is what they believed was best for them.

“You don’t need tons of money to do it,” she said. “You can still be really really successful, because it’s a super supportive community … There’s always something for everybody, especially here.”

Growing up in a homeschooling family, Keshia Villas said her family always had friends who wanted to homeschool, but were a two-income family and felt they didn’t have the means to do so.

This year, her mother, Rhonda McAfee, started the Homeschooler Education Network to help working families make homeschooling a reality.

“It’s more of that model of ‘It takes a village to raise a child,’ ” Villas said. “When it comes to homeschooling, just drawing from your community too, and drawing from resources and other people that you meet along the way.”

Learn more from KCUR 89.3 about McAfee and the rise of Black families in Kansas City who have adopted homeschooling.

Opportunity

Villas was homeschooled since she reached school age.

Now, as an adult, she’s grateful for the experience, though it wasn’t all that different from the traditional school experience. She was a cheerleader, competed in debate, played basketball and participated in plays through her church.

“There’s just so much available,” Villas said.

She started taking classes at Johnson County Community College while she was still in high school. The credits she earned there allowed her to later graduate from Kansas State University in just three years.

But what she really values from her homeschool education was the ability to be an independent learner.

“I feel like as a homeschooler, I was kind of prepared to know that I can do anything,” Villas said.

After college, she started her own language company, Bridge the Gap, which matches native Spanish speakers to folks wanting to learn the language. It’s not what she studied in college, but she knew she could develop the skills to make the company successful.

The freedom of homeschooling also allowed the Villas family to teach topics they found important such as African American history and literature by Black authors.

“My parents, and my mom made sure it was a priority to teach us that history correctly,” Villas said.

Her early education helped Villas to feel “confident in (her) uniqueness.”

“I feel like, if I had been in a public school setting, I would have blended in, if that makes sense,” Villas said. “Whereas now, because I was homeschooled, I feel empowerment to be who I am.”

Villas said she felt better prepared for adult life because of the support she had from her parents growing up.

This is what Edwards hopes to give her daughters as they become young women. She wants to teach them skills outside of the classroom, like cooking or gardening, and lead discussions with them about difficult subjects.

For example, while her girls were still in private school, Edwards said there were lots of kids who were watching pornography at school. Parents kept hearing of other sexual situations arising.

“If we did not have a choice to homeschool, we would just have to do the best we could … and just wish for the best,” Edwards said.

Now, Edwards gets to lead conversations with her girls around those topics. Often, she said they’ll watch movies and documentaries together and then discuss some of the more adult topics afterwards.

“We felt like we should be able to have those types of conversations, and we wanted it to be introduced in the right way,” Edwards said.

This spring, Edwards and her girls are packing up the car, choosing a direction and hitting the road.

“The great thing about it is they’re not missing school because they can work on their stuff while we’re in the car, and we’re also learning as we’re sightseeing, and seeing some of these monuments and whatever the place that we’re at has to offer.”

Edwards is excited for the opportunities her girls will have, like taking college classes at the community college while they’re still at home, but mostly she’s excited about the time she has with them.

“Hopefully the pictures, and all the memories that we will create from that will be something that they will cherish for a lifetime,” Edwards said.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.