Missouri Cattle Producers Slash Herds Amid Worsening Drought ‘All The Grass is Gone’

Published July 20th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Drought conditions in Missouri are making it near impossible for cattle producers to take care of their entire herd. (Cami Koons | Flatland)Bruce Mershon cupped a smartphone to his ear as he waited to get into his white pickup truck.

He was listening to a cattle auction online, hoping to hear that a friend’s cows were selling for a decent price.

Selling cows is part of the business. But worsening drought conditions in Missouri are forcing folks like Mershon to sell more than normal.

In a typical year, Mershon sells about 15% of his herd, usually older cows that end up at the supermarket meat counter. This year he expects he’ll have to liquidate nearly twice as much of his 2,200 head.

There’s a simple reason. The pasture where his herd grazes is drying up.

“Some (producers) are just selling everything,” Mershon said. “There’s nothing there. All their hay and all the grass is gone.”

As of July 11, 99% of Missouri was in “abnormally dry” or worse conditions, 58% had severe drought conditions and 25% faced extreme drought conditions.

Livestock producers in the state are most immediately affected by the drought conditions.

Scant spring showers yielded parched pastures. Producers have had to supplement their cattle’s diets with hay and other grains much sooner in the season than normal.

Many ranchers don’t have the resources to sustain this through the fall and are forced to make the tough decision to sell. Producers in drought regions are eligible for resources through the state and federal governments. But a substantial amount of rain is the only lasting solution.

No Forage, No Hay

Mershon and his wife, Tracey, operate on land that’s been in the family for more than a century. One of the barns on the property was built by Bruce Mershon’s great-grandfather.

In the 20 years since the Mershons started raising cattle, Bruce and Tracey have grown the operation from about 150 head to 2,200 cows.

The Mershons breed via artificial insemination, raise some calves to keep as breeding stock, and send the rest to feed lots to be finished and butchered for meat. They keep most of the heifers (female cows for breeding) to build the genetics of their herd.

So far into this dry season, the Mershons haven’t fared too poorly. They found a producer up north who wanted some younger cows for his herd and bought some of Mershon’s calves.

“The market is in such a position that I’m having to sell way cheaper than I anticipated,” Bruce Mershon said. “I thought they would be worth $600 or $700 more a head — if we’d had good, normal conditions today — than what I sold them for.”

Nationally, cattle inventory has declined by 15% since 2018. Those decisions down on the farm are sending ripples through the food chain that are ultimately felt in higher beef prices at the supermarket.

Sticker Shock at the Meat Counter

Thankfully for the Mershons, that means cows that are culled because they are too old or no longer producing continue to sell for a decent price.

They ranch outside of Buckner, Missouri, on leased land and on what Mershon called “daily lease” properties, where he pays a property owner to take care of his cattle. These are spread throughout the state, which has been both good and bad during this time.

“We have cattle (in) between 10 and 15 counties in the state all the time, and we’re diversified north to south, which makes our cost to produce higher… but it has at least afforded us some diversity with our forage production,” Bruce Mershon said.

Cattle they keep up in northwestern Missouri, are fine. The cattle they keep in places like Stockton, Missouri, which sits in an “extreme drought” area, are something of concern.

“Whether I owned it, or they own the land, it doesn’t matter. If there’s no forage, there’s no forage,” he said. “So we have to make hard, hard choices.”

All summer the Mershons have been rotating cattle to different grazing grounds and trying to wait out the weather.

It may be too late to save pasture this year. Even if he got a couple of inches of rain, the cool-season fescue on most pastures wouldn’t be able to grow in such hot temperatures.

“We needed to make lots of grass in May and early June,” Mershon explained. “You can’t really make up that ground right now.”

Farmers and ranchers are beholden to the weather. But what many don’t understand is the lasting effects of a bad summer drought.

Mershon Cattle will usually own its cows for 8-10 years, and it takes about 3-4 years before a calf has matured, carried and delivered a profit. Producers and consumers will likely feel the effects of this summer drought for that same 3-4 year timeline.

“When you’re raising mama cows in Missouri, it’s a really long time horizon that you’re working,” Mershon explained.

With each season, they improve the genetics of their herd, which is what makes it so difficult to just start over.

“You can’t just go buy the same genetics — that’s what you’ve been investing in,” Mershon said.

So, while he wants to keep them, he can’t. Mershon is having to sell and at a cheaper price per head.

This means when the Mershons want to bring the herd back, the overall inventory will be down, and the price of heifers will be up.

“You’re maybe selling it today for $1,800. It may cost you $3,000 to buy her back a year from now,” Mershon said. “Not only are you losing on the drought part of it, but (it’s) unfortunate timing for this.”

Next to a metal hoop barn where the Mershons kept freshly weaned cows, stands two arched structures, about half full of circular hay bales.

“We were already kind of behind on forage last year. We weren’t in a desperate drought situation in Missouri last year, but our hay production wasn’t very good,” he said.

So, Mershon started to think of other ways to supplement their cows’ diets by using the corn stalks and remnants left in his brothers’ fields after harvest. He also added distillers grain (a byproduct of ethanol production) as filler in the cattle diet. While these work to keep the cows fed, it comes at a higher cost than grazing on pasture.

This year he started without the usual reserves of hay. His hay harvests are about one-third the yield of a normal year. And the hay he bought was at an inflated price.

“We’ve got a ways to go,” Mershon said. “So we are liquidating some (cows), we’ll just kind of keep trying to purchase (hay) hopefully use more corn.”

But Didn’t It Just Rain?

A single line of thunderstorms doesn’t solve a drought.

“Individual precipitation events rarely make a difference,” said Curtis Riganti, a climatologist with the U.S. Drought Mitigation Center.

Each week, the U.S. Drought Mitigation Center, based at the University of Nebraska Lincoln, uploads a new drought map illustrating conditions down to the county level.

Just as droughts can’t be resolved with a single rainstorm, drought conditions don’t happen overnight.

Missouri’s currently dry state started this spring when the normal spring showers didn’t come. It was exacerbated by increasingly hot weather and a continued lack of precipitation.

Right now, the state is mostly experiencing short-term drought effects like dormant lawns, low lake/pond levels, agricultural impacts and increased use of groundwater sources.

A drought that persists longer than six months or so can lead to more long-term implications like depleted reservoirs and aquifers. These are issues plaguing Kansas, which has faced increasingly worse drought conditions since the summer of 2021.

Last month was the hottest June ever recorded on earth. High temperatures can cause increased evaporation and even dryer ground.

For drought conditions to improve, Missouri needs to see not only increased precipitation, but cooler temperatures.

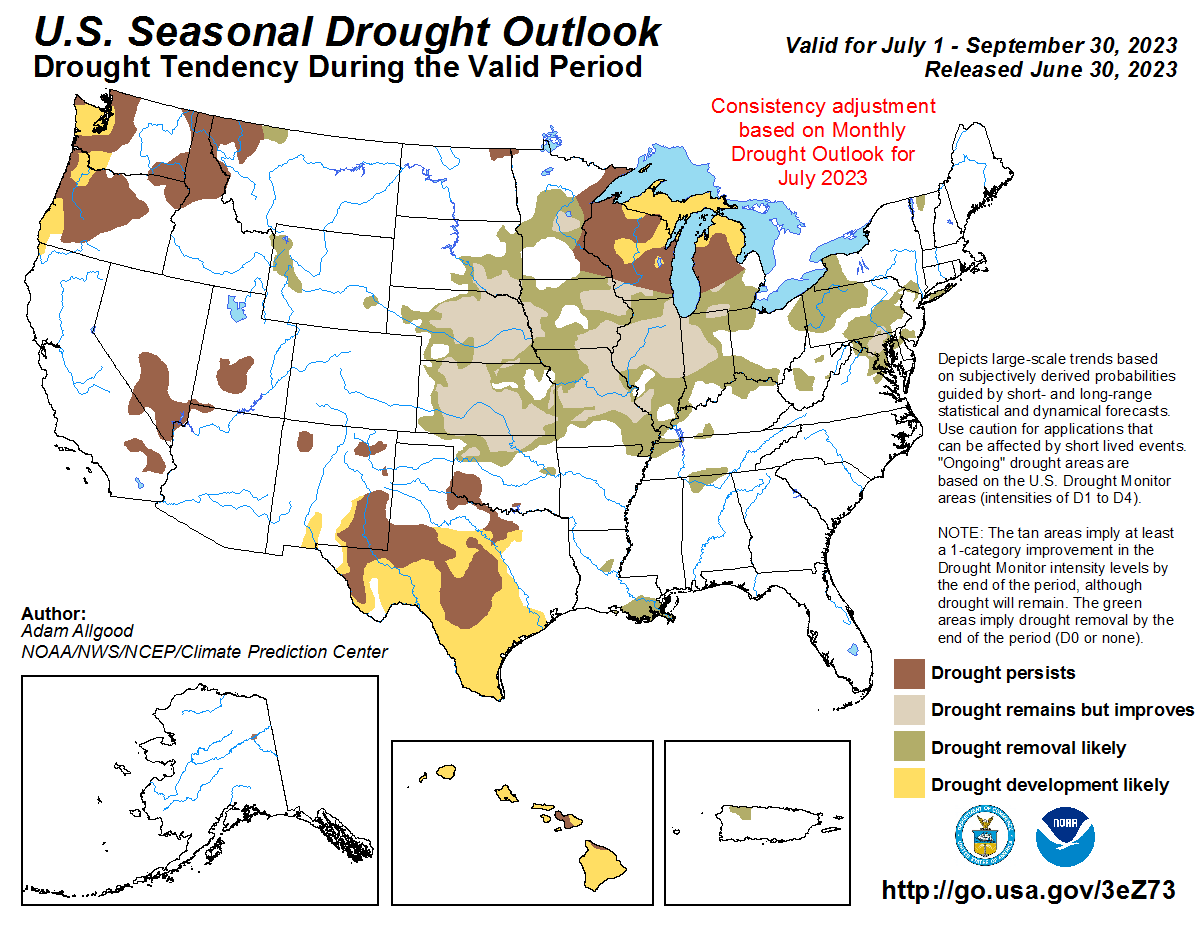

Unfortunately, the U.S. Drought Outlook map, prepared by the National Weather Service, predicts drought conditions in Missouri will persist, though slightly improve, through September.

Riganti encourages farmers and landowners to contribute to the Condition Monitoring Observer Reports. This gives folks at the Drought Mitigation Center on-the-ground feedback about the effects and spread of drought in certain areas.

The accuracy of the drought map is important because it’s used to determine a landowner’s eligibility for federal and state assistance programs.

Seeking Assistance

Elizabeth Kerby, an engineer with the water resources center in the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, has fielded a lot of calls in the past couple of months.

Most calls are from folks who live in counties that don’t have the proper drought recognition to receive help but find themselves very much in drought conditions.

“Our precipitation has been pretty scattered, so we’re really trying to get people to submit these conditions monitoring observation reports,” Kerby said.

Missouri was in a similar situation last fall. In October 2022, the entire state was in abnormally dry, or worse, conditions. This year, the dry months started in the spring, coinciding with the planting season.

At the end of May, Missouri Gov. Mike Parson issued an executive order declaring counties that were or would be labeled as “moderate drought” would be eligible for resources.

Missouri State Park land and Missouri Department of Conservation land were then opened to producers in drought conditions. Folks could call and request to harvest hay from some of this public land, or to pump water from boat ramps in the park to be used agriculturally.

When Flatland spoke with the Department of Natural Resources at the end of June, few had taken advantage of the program. The resource map this week shows that most of the haying opportunities have been reserved.

These resources were part of the department’s drought mitigation plan, which was updated this year from its 2002 version.

“This is kind of our test year for the document,” Kerby said. “We’re really trying to make it a living document — so what works, what doesn’t work, we’re going to edit the docs, so that it can be a working plan.”

Compare: Missouri Cattle and Hay Areas in Drought.

The Department of Agriculture is working closely with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and the Department of Conservation on their drought assistance protocols. Director Chris Chinn said the best resource from the Department of Agriculture right now is its hay directory, where folks who have hay for sale can advertise to producers.

“Normally this time of year, we have green grass in our pastures and the cattle are grazing on that grass,” Chinn said. “This year, the grass has not grown, it’s not green anymore, so they’re having to use their winter feed supply, which is that hay, to supplement their cattle diets right now.”

Chinn also warned of hay scams, which have been abundant this year.

Moving forward, the department encourages farmers to work with their University of Missouri Extension offices to learn about regenerative practices like rotational grazing or the implementation of warm-season grasses, which are more tolerant to drought.

Additionally, Chinn encourages Missouri producers to take advantage of the Agristress Helpline if they are feeling stressed during these conditions.

“What makes this stress line unique is that the people on the other end of the phone understand agriculture and farming, and so they’ll be able to relate with the farmers and ranchers who are calling in,” Chinn said.

While the drought affects farmers and ranchers most, everyone can help by conserving water during this time.

“If we don’t get some rain pretty soon, we’re really going to start running into a shortage of water,” Chinn said. “So anything that people can do to (conserve) water and a time like now is going to be very important.

“Really, we need to pray for rain, because that’s going to be the only thing that gets us out of this.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has several programs to help alleviate some of the extra costs that come during a drought. Folks in eligible drought conditions (severe drought or worse) are eligible for the Livestock Forage Disaster Program and the Emergency Assistance for Livestock.

Mike Deering, the executive vice president of Missouri Cattlemen, said these programs help, but no amount of aid makes up for a season like this.

“It is the worst spring I’ve seen in my lifetime,” Deering said. “I think some of the older cattle producers and farmers, ranchers will tell you the same thing.”

Deering referenced the drought map. The places in Missouri with the most severe drought coincide with the biggest regions for cattle production in the state.

“Livestock markets throughout the state are having mass liquidations of cows come through their barns, people are giving up and selling out because there’s really no relief in sight,” Deering said.

“There are some cattle producers in the state who haven’t stopped feeding hay since the winter, just because it’s been that dry,” Deering said.

Deering also fears that the drought conditions will affect the passage of land to newer generations of cattle producers.

“People give up and they sell that land, or it gets tilled up into crop production and seldom does it ever go back into livestock production,” Deering said. “At the end of the day, that’s what sustainability is all about — being able to leave that land to the next generation, and preserve land and resources for that generation.”

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.