- Home | News & Issues |

- Missouri Farmers Embrace Practices to Protect Waterways

Missouri Farmers Embrace Practices to Protect Waterways Sustainable Methods Are Good For the Farmer and the Planet

Published June 20th, 2023 at 1:37 PM

Above image credit: Kent Wamsley describes the protected Dunn Ranch Prairie, like a "quilted tapestry" because of the various height and color of the plants. (Contributed | The Nature Conservancy)From his home on Dunn Ranch Prairie in northern Missouri, Kent Wamsley is witness to a thriving grassland.

Buffalo graze, butterflies and pollinators buzz about, birds and small animals burrow in the coverage of tall native plants, and below the surface deep roots instigate soil health and prevent runoff into nearby waterways.

Dunn Ranch Prairie is an area of more than 3,000 acres of grasslands protected by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), which has worked to preserve the area for the past two decades.

In addition to reviving Missouri’s prairie ecosystem, Dunn Ranch Prairie serves as a concentrated example of the conservation efforts promoted by TNC and other entities.

Incentive programs and education around regenerative farming practices like efficient nutrient management, rotational grazing, cover crops and buffer zones have increased in the past couple of years. Increasingly, producers are willing to adopt these practices because they help both the environment and their profits.

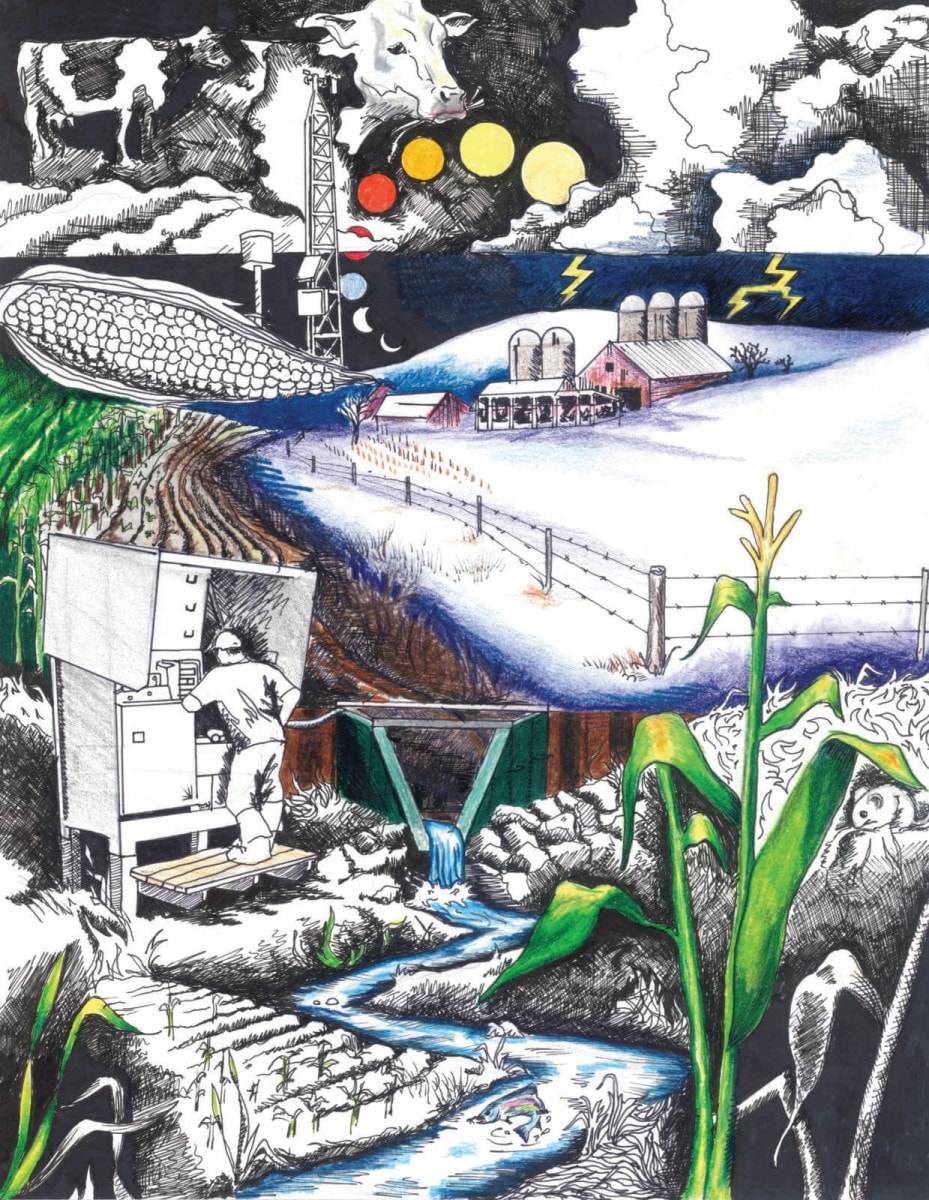

In addition to increasing soil health, these practices help to mitigate nutrient runoff and water pollution.

According to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources 2020 Integrated Water Quality Report, 28% of assessed lakes were impaired for their designated uses. The report showed urban and agricultural runoff as “major pollutant sources.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that agriculture, which applies 12 million tons of nitrogen, and 4 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer annually, is the leading cause of water quality impacts on rivers and streams.

Nutrient Management

Wamsley is the grasslands and sustainable agriculture manager for the Missouri chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

The Nature Conservancy, since its start in 1915 (originally as the Ecological Society of America), has protected lands and waterways by buying parcels of endangered land and promoting conservation practices.

As a key element of its protection of waterways, TNC helped to create the “4R” nutrient management program. It encourages farmers to apply nutrients (fertilizer) at the right rate, the right time, from the right source and the right place.

Common Sense

The four Rs of a specific field are determined by frequent soil tests.

The soil test will show the nutrients in the soil and clue farmers in on the nutrients that need boosting for each crop.

TNC, along with partnering organizations the Missouri Fertilizer Control Board, Missouri Agribusiness Association, Missouri Corn Merchandising Council and Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council, support and educate Missouri farmers who adopt the program.

“I think the biggest thing is just educating people on the decisions that they make,” Wamsley said.

The goal of the 4R protocol is to give the soil what it will be able to sponge up, when it’s most absorbent. Nutrients taken up by the soil won’t get washed downstream.

The crop and pastureland, when fed and able to absorb the proper amount of nutrient, are more productive. Farmers also spend less on costly fertilizers.

It’s really a win-win situation. So why doesn’t everyone follow these practices?

There are a variety of reasons: lack of knowledge about the practices, reluctance to change, or fear of an unproductive season.

Landry Jones is the conservation grazing specialist for MFA, a Missouri-based farm supply and marketing cooperative.

Jones said the biggest part of his job is convincing producers to think “outside of the box” on their management practices.

“So many times, producers get into the habit of managing their operation like their father or grandfather, whether they want to or not,” Jones said.

MFA has a program, similar to 4R, called Nutri-Track, which uses soil sampling to “spoon feed” nutrients where they are most needed.

Other Practices

Jones, who collaborates with several organizations, including the Missouri Department of Conservation, promotes other conservation practices, like rotational grazing

In Missouri, the majority of pasture is Kentucky 31 fescue, a grass that can be easily overgrazed and comes back each season. Jones advocates for livestock producers to rotate herds through more diverse grazing pastures, often with the introduction of native plants.

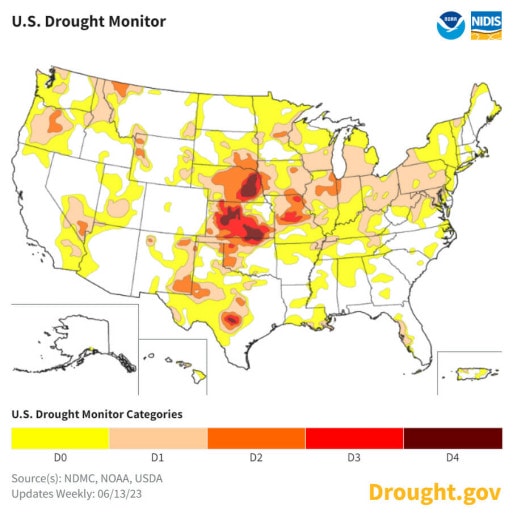

These native prairie grasses are more drought tolerant than fescue, which is a huge advantage.

Rotational grazing works with diversified pasture in that different grasses are most productive during different seasons.

Fescue, for example, is best grazed during the spring and fall. Native warm season grasses are best in the summertime, meaning the two could complement each other in a livestock operation.

“That’s kind of where and why native plants have their fit, because they grow when fescue isn’t growing, but they typically need to be in separate fields from fescue,” Jones said.

Fescue also has its highest toxicity in the summer months, so it’s beneficial for the livestock to have a different feed.

MFA holds a strong principle of stewardship, which informs Jones’ position and the co-op’s conservation strategies.

“We want to make sure we’re doing the right things on the land, to the land, in a way that is going to maintain the health of the land that it’s there for future generations,” Jones said.

Jones began promoting native forages in 2019. Adoption started slowly, but has picked up significantly in the past several years. Recent drought conditions have sent producers searching for more resistant vegetation.

Compounding Benefits

Lucas Miller and his cousins Cordell and Michael Dunlop farm close to 7,300 acres in Linn County, Kansas.

The century family farm rotates corn and soybeans. About 10 years ago, before Dunlop’s father retired, the family started to implement the Nutri-Track and soil sampling programs through MFA.

“It’s good for the environment and it saves us money,” Cordell Dunlop said.

The family originally justified the soil sampling cost with a desire to regulate the PH of their soil. After realizing the effectiveness of the process, they used it to calibrate their application of potassium, phosphorus and later nitrogen.

“It helps you be more efficient with your fertilizer,” Cordell Dunlop said.

This style of application, as opposed to a blanket application of the same amount of a nutrient over an entire field, saves on fertilizer costs, but also ends up being better for the crop itself.

“Where it’s probably made us the most money is where you’re focusing on your best spots,” Lucas Miller said.

Via soil sampling, the Nutri-Track program looks at 2.5-acre grids across a farm and determines what nutrients each section needs. That data goes to technology in the trucks, which distribute the nutrients at the necessary variable rate.

This system also considers the amount of nutrient lost on the land, based on its production rates, and adjusts its calculations accordingly.

Under the program, the family has seen an increase in crop production.

Cordell Dunlop said for his father and other older generations of farmers, the transition to Nutri-Track systems of nitrogen application has helped streamline practices and make them safer.

Before this, the family would haul anhydrous (ammonium nitrate) out to the fields to spray. The process was not only very time-consuming, but also dangerous as the chemical can cause respiratory issues.

Now, the Dunlop operation uses a type of liquid nitrogen that can be sprayed in the same way they would apply an herbicide, which saves them a step.

“It’s just an easy way to change things up and not add steps to what you’re doing,” Michael Dunlop said.

Soon, the family hopes to implement some buffer zones to complement their no-till and spot nutrient efforts in preventing runoff.

Wamsley sees this often. Once a producer integrates one practice, they are more likely to adopt other sustainable practices.

“The whole idea of having those soil tests in place and doing something through the 4R work is just coming alongside the producers and helping them be better stewards of the land and the resource that is so valuable to them,” Wamsley said.

Right now, he said it’s the “perfect storm” for a producer to begin implementing these practices, due to the wealth of available funding. Wamsley hopes folks will decide to implement 4R, as well as other practices.

“The 4R is not the end all be all silver bullet,” Wamsley said. “It’s a piece of the puzzle that can help lessen the financial impact for producers who are trying to do the right thing and who want to do the right thing, but might not have all the resources to make those things happen.”

Last fall the University of Missouri Center for Regenerative Agriculture was awarded a $25 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Climate-Smart Commodities program.

The funding will give incentives to Missouri producers who implement climate-smart practices.

Joseph LaRose, an advisor for the Missouri Climate-Smart program, said incentives should be made available later this summer, and the department expects applications from thousands of Missouri producers.

Planting cover crops is the most common practice. But other climate-smart practices include nutrient management, rotational grazing, implementing native forages and planting trees on the edges of pastures, among other practices.

These practices lead to better overall soil health, which in turn grows healthier plants, and keeps nutrients and soil in the ground — not in the waterways.

“These days most of the fertilizer farmers put on field runs off,” LaRose explained. “Crops are only capturing a small percentage of that, and if it doesn’t get captured by something, that just goes into the water and then eventually it gets into drinking water.”

Small and underserved farms are candidates for the “climate-smart fieldscapes,” a section of funding for these farms to implement at least three climate-smart practices.

LaRose said the conservation efforts of these practices multiply when implemented together.

“If you if you have a perennial buffer, and you do no-till … and you’re doing cover crops, you can knock erosion down by 90% or more,” LaRose said. “When it’s one of those individual practices, it’s not going to get all the way there.”

LaRose said education, in addition to funding, is vital to the adoption of these climate-smart practices. To that end, the Center for Regenerative Agriculture will host workshops and provide resources to producers.

Increasingly, Wamsley sees farmers adopting these practices. It’s in part out of their commitment to stewardship, but also because of market demands. As prices for materials rise and drought or flood become more common, producers are looking to maximize their efficiency and make sure their land can continue to produce for years to come.

Some states have mandated the implementation of these practices.

In Missouri, the adoption of cover crops, informed nutrient application, buffer zones, rotational grazing and similar practices is elective, and Wamsley sees it growing in popularity.

“I applaud the ranchers and the farmers in Missouri for jumping in on these things,” Wamsley said. “They are willing to do what’s right, and I’m glad that we’re getting plenty enough dollars and resources to come alongside and help them to achieve their goals that they have for that land.”

This article has been updated from a previous version.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

Tags: agriculture • Climate Smart Practices • Cover crops • Drought • Native Plants • Regenerative Agriculture • Report for America • Rotational Grazing • Sustainability • The Nature Conseravancy

Like what you are reading?

Discover more unheard stories about Kansas City, every Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!

Check your inbox, you should see something from us.

Ready to read next

Art in the Loop Kicks Off 10th Year in Downtown

Read StoryRelated Stories

A ‘Green Glacier’ is Burying Prairies, Threatening Ranchers and Wildlife

A juggernaut unleashed by humans is grinding slowly across the Great Plains, burying some of the most threatened habitat on the planet beneath dense junipers and shrubland.

by Celia Llopis-Jepsen, Kansas News Service | 04-23-2024