Memorial Honors Hundreds of Black People in Liberty’s Unmarked Graves Liberty African American Legacy Memorial to be Dedicated June 18

Published June 10th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

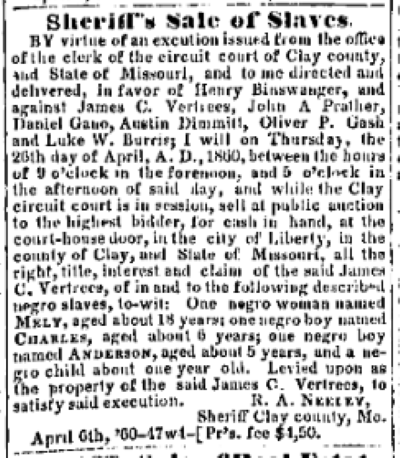

Above image credit: A series of posts, or bollards, marks the formerly segregated section of Fairview Cemetery in Liberty, where more than 750 individuals are believed to be buried, many of them in unmarked graves. (Brian Burnes | Flatland)Next week the long-invisible dead of Liberty, Missouri, will be rendered less so.

The Liberty African American Legacy Memorial, scheduled to be dedicated June 18 as part of the community’s Juneteenth celebration, is nearing completion.

It honors the lives of 761 Black individuals who have been confirmed to be interred, mostly in unmarked graves, in the formerly segregated sections of Fairview and New Hope cemeteries in Liberty.

In 1860 the 3,455 enslaved persons counted in Clay County during that year’s census represented more than 26% of the county’s population.

For anyone visiting Fairview Cemetery in recent years, that’s been hard to visualize.

While the bulk of the burying ground is crowded with obelisks, monuments and other grave markers, almost all of the memorials presumably placed within the approximately six-acre, once-segregated section near its eastern border have been lost to time.

The new memorial will mark that approximate spot, acknowledging those deceased residents whom organizers say – after enslaved persons in Missouri gained their emancipation in 1865 – went on to help build contemporary Liberty.

“We want everyone to know who these people were, people who helped create a community despite systemic racism,” said Cecelia Robinson, a former William Jewell College faculty member who has served as historian on the project.

The memorial has attracted financial support from corporate, nonprofit and government sponsors.

“We have done well on the fundraising and we now have the core part of the project completed,” said AJ Byrd, president of Clay County African American Legacy Inc., the Liberty nonprofit whose members have planned the memorial since 2018.

“This is about healing our community.”

Close to 500 individuals also have contributed, Byrd added.

Of those, three will be identified as “Reconciliation and Reparation Donors” on the memorial as having made financial contributions “In Memory Of All Persons Enslaved by Our Families Buried Here.”

The memorial has been planned in context of a larger, continuing dialogue regarding Liberty’s complex slavery legacy.

The status of a Confederate memorial located just a short walk from the new memorial continues to be debated by those who want to see it removed and relocated, and those who insist that it should stay. Meanwhile, students at William Jewell College, joined by a faculty member, recently have investigated the role of enslaved persons in the school’s founding and construction.

The school has formed a separate commission researching similar questions. William Jewell College is among the memorial’s donors, Byrd said.

The three individuals named on the new cemetery memorial, meanwhile, say they are pleased to support its construction as a unique opportunity to address their own families’ role in the community’s slavery past.

They are:

- Robert Withers II, a descendant of Abijah Withers, who arrived in Clay County from Kentucky in the 1830s and who owned enslaved persons.

- Thomas L. “Tad” Kelly, a descendant of O’Fallon Dougherty, a son of “Major” John Dougherty, a 19th century frontiersman who in 1860 owned 64 enslaved persons on his Clay County estate.

- Robert Weagley, a descendant of Elvira and Ephraim Murray of Liberty, who owned enslaved persons. In 1904, according to Weagley, Elvira participated in the dedication of the same Confederate memorial currently being debated.

“I think it is a positive and proactive step to have this new memorial built,” said Weagley, retired department chair of personal financial planning at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

“Racism is one of the biggest problems that exist in our country. Many people are afraid to talk about it. Most people want to ignore it. This memorial helps address some of those things in a positive way. Frankly, it stirs the pot in a little way, to get these things talked about.

“I also had the nagging fear that members of my own family actually might have owned some of those people before they were buried there.

“I don’t know that – but it would not be a surprise.”

While Weagley had known about his family’s slavery legacy for much of his life, Kelly only learned of his family’s involvement in 2019. That’s when an aunt asked him to edit a family history that referenced the enslaved persons once owned by family patriarch John Dougherty.

“My heart stopped,” said Kelly, a growth equity investor in Denver, Colorado.

“It was a turning point for me. It was clear my ancestors had lived a good life and that a lot of that had been based on the work on enslaved people.

“That obviously struck me as problematic – that’s the nicest possible word.”

Withers, meanwhile, came to confront his own family’s slavery legacy in a similar way. Years ago, while going through family papers, he came across a memoir written by his grandfather.

“This is personal to me,” said Withers, a retired film instructor and pharmaceutical advertising copywriter in New York City.

Withers cites a story included in his grandfather’s memoir, which collected accounts detailing life on the family’s Clay County property before, during and after the Civil War. One story concerns Noah, an enslaved person who was beaten after being accused of stealing chickens.

When Noah later chose to speak lightly of the incident, according to the memoir, the Withers family sold him.

“He made a joke of this to the master or missus and he was sold,” said Withers.

“I would have been the kind of guy who would make a joke about stealing chickens. And if I had been an enslaved person on the Withers farm, I would have been sold down the river.”

Making Amends

Kelly had not known of his family’s slavery legacy.

Nor had he known much about “Major” Dougherty, one of western Missouri’s most documented frontiersmen and builder of what often was called the grandest antebellum mansion in Clay County.

A Kentucky native who arrived in St. Louis as a teenager in 1809, Dougherty hired on with a fur company expedition to the upper Missouri River region.

While serving in the fur trade he became conversant in several American Indian languages. From about 1827 through 1839 he worked as a federal government Indian agent – earning the title of “Major” not because he served in the U.S. Army but because Indian agents, then working under the umbrella of the War Department, received the same $1,600 annual salary that an Army major earned.

As an Indian agent, Dougherty witnessed the 1836 negotiations between explorer and federal Indian Affairs Superintendent William Clark and representatives of several Indian nations over the land that became the Platte Purchase, which added more than 3,100 square miles to the northwest corner of Missouri.

Dougherty retired as an agent in 1839 and in 1840 was elected to a term in the Missouri General Assembly. After that he and a St. Louis partner supplied goods and livestock to U.S. Army forts.

Dougherty acquired his Clay County property in the 1830s and in 1855 completed building his mansion, located some seven miles northwest of Liberty and sometimes called the “Dougherty Brick,” for a reported $20,000.

Dougherty named his house “Multnomah,” a reference to Multnomah Falls in the Columbia River Gorge of Oregon.

Dougherty also owned enslaved persons.

“When he began to build this mansion, in 1853, bricks were burned by slave labor,” the Kansas City Star reported in 1963 after Dougherty’s home, by then long neglected, had burned.

Documents maintained by the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis include several bills of sale for enslaved persons.

A slave schedule from the 1860 census listed 64 enslaved persons owned by Dougherty, said Mark W. Kelly, a Kansas City area archaeologist and attorney who has explored much of the former Dougherty estate.

Kelly – no relation to Tad Kelly – first encountered the Dougherty property in 1995 when he surveyed portions of it for a proposed sewer line.

Items he came across included an iron wagon wheel hub handcrafted by a blacksmith and a top-heavy stone cutter’s hammer, used for extracting the limestone often used in frontier construction.

Development of the area – today in Kansas City, North – went forward.

But Kelly found himself fascinated with Dougherty, devoting many subsequent years to researching the frontiersman’s story. Having grown up in New Mexico a fan of fur trapper and Indian agent Kit Carson, Kelly was intrigued when he discovered that Carson and Dougherty had been acquaintances.

“I’ve always been an admirer of those ‘mountain men,’ ’’ said Kelly, who in 2013 published “Lost Voices on the Missouri: John Dougherty and the Indian Frontier.”

Joining colleagues with the Kansas City Archaeological Society, Kelly over three weekends examined the site of the old Dougherty mansion, excavating the southeast and northwest corners of the home’s stone foundation, as well as several Mother of Pearl buttons, recovered in the basement.

In separate investigations Kelly also found evidence of three cabin sites perhaps once occupied by enslaved persons. Two of them still survive, he said, on the approximately 54 acres that today remain undeveloped from the original Dougherty property, which once included just under 5,000 acres.

Last autumn he took Tad Kelly out to the site.

By then Tad Kelly had hired a genealogist, asking her to learn more about the enslaved persons once owned by Dougherty, as well as their descendants.

“I needed to dig in and learn more,” Kelly said.

“I needed to learn to what extent the role enslaved people had in building my ancestor’s prominence and wealth, building his house, and growing the agricultural products on his property.”

Kelly is a recent former trustee of the Denver Foundation, the city’s oldest and largest community foundation whose strategic plan, he said, focuses on racial equity. Also, as the former chair of the foundation’s investment committee, he helped bring a racial equity perspective to the foundation’s investment strategy.

Kelly has informed Clay County African American Legacy Inc. directors that he will be making annual contributions in support of the Liberty nonprofit’s projects and programming.

“So, supporting the memorial project became an important thing to do, especially given the near certainty that descendants of the people that my ancestors enslaved are buried there,” Kelly said.

One of the tenets of effective repair, Kelly added, is the role of testimony, “which involves shining a light on the current and historical racial injustices in our country.

“There is a broader issue here for folks like me, about getting educated about that history. Most of us take American history in high school, but we are simply not taught this history.

“But it’s out there – it’s definitely findable. And once you get the facts, you can never again see the world the same way, and you realize the need to acknowledge the harm that was done and then figure out how you are going to make amends.

“The learning never ends, but the making of amends is just beginning.”

As His Grandfather Remembered It

While Kelly’s November visit represented his first trip to Liberty, Robert Withers II grew up there and knew its history.

A grandmother, Ethel Massie Withers, founded the Clay County Historical Society and wrote the county’s centennial history in 1922.

Her husband, Robert Steele Withers, was a farmer who during World War I served as Clay County food administrator.

He was also a writer, contributing articles to the Missouri Historical Review and serving as a frequent source of historic vignettes to the Liberty Tribune, often under the headline of “Old Folk’s Tales.”

So the younger Withers knew the Clay County story. Still, he was startled when he came across a copy of his grandfather’s memoir, typed on onion skin paper and entitled “As I Remember It.”

It never had been published.

“I stumbled upon this while going through papers after my parents had died,” Withers said.

The volume detailed how patriarch Abijah Withers had arrived in Clay County from Kentucky in the 1830s, bringing with him an enslaved person named Merritt Withers. The two worked together to construct a log cabin for Abijah’s family as well as three cabins for Abijah’s enslaved persons, on property today located perhaps a mile south of Liberty.

Abijah then returned to Kentucky to bring back his wife Prudence and their children.

When they arrived back in Clay County perhaps a year later, Merritt Withers was still there, on the farm, waiting for them.

“I have often speculated what made Merritt hold down the Withers farm for a year when he was an enslaved person,” Withers said.

“Why didn’t he run away?”

Today Withers can only wonder about that and ponder his grandfather’s description of farm work before and after the Civil War.

“One thing I was struck by was how hard people worked – 10 to 12 hours a day out in the fields during the growing season, while working alongside enslaved persons,” Withers said.

“That was curious to me, because that was not what I had read about the slavery culture in the Deep South.

“I was just really interested in that.”

Whatever Merritt’s reasons for staying on the Withers farm in the 1830s, he went on to enlist in the U.S. Army following a November 1863 order approving the enlistment of able-bodied men of African descent in the Union army.

Merritt Withers (some government documents spell the name “Merrit”) was one of 67 Black men from Liberty who enlisted, and visitors to the memorial website can examine papers documenting Merritt’s 1864 decision to enlist.

He survived the Civil War and, according to the memoir, became a substantial citizen of Clay County after emancipation.

“He was a barbecue master at a time when barbecues were big community events, almost political events,” Withers said.

“He became a Republican. There is a story about him standing up at a town meeting and speaking. My grandfather described him as a large man, with blond hair, and dreadlocks.

“He was a fearless character in a way.”

Robert Withers II found other revelations while reading between the lines of his grandfather’s memoir.

“There was this kind of skewed picture in how my grandfather seemed to take some things for granted,” Withers said.

“It wasn’t white supremacy in the modern sense of that term. It was more about how he just assumed the right of white people to make decisions about African American people and their lives.

“For example, my grandfather wrote about how the families that held enslaved persons sometimes would try to arrange for certain younger enslaved persons to be kept together on the same farms.

“My family, in a weird and subliminal way, seemed to have been proud of owning enslaved persons in this ‘good’ way,” said Withers

“But slavery was a crime against humanity.”

Withers edited his grandfather’s manuscript, adding his own essay and publishing it himself underneath the title of “Monsters In Time.”

The project, he believes, helped him respond to his family’s slave-owning past.

“I tried to come to terms with that heritage,” he said.

Today the Withers name remains familiar around Liberty. While the last parcel of the original Withers family farm has recently been sold, Withers said, the Withers Branch of the Mid-Continent Public Library stands at 1665 S. Withers Road in Liberty.

The Liberty African American Legacy Memorial, Withers added, seemed a unique opportunity for him to address his family’s legacy.

”I am glad to go on record in supporting this project in the spirit of reconciliation and reparation,” he said.

Today researchers with the new memorial project have confirmed Merritt Withers as being among the 761 Black residents interred at or around the memorial site.

Robert Withers II’s grandparents – Robert and Ethel – also are buried at Fairview Cemetery.

‘A drop in the Bucket…’

While Robert Weagley had been aware of Clay County’s slavery past and his family’s role it, he had not known about the Legacy memorial project.

That changed during the 2020 COVID pandemic shutdown, when Weagley resolved to investigate more closely his family’s slavery legacy and what, if anything, he could do to reconcile himself with it.

After joining a Liberty history group on Facebook, he received a tour of Fairview and New Hope cemeteries and learned of the planned memorial.

He decided to help raise money for it.

“It’s a private statement of my support in honor of these men and women who helped build this city,” he said. “I have this odd sense of responsibility in that I am the only one in my family who can give back now.

“So, I am proud to be a part of this. Who wouldn’t be?”

To his own involvement in the new memorial, Robert Weagley brings unique Clay County bona fides.

His father, Robert Weagley, Jr, served a term as Liberty mayor in the mid-1970s.

A great-great grandmother, Elvira Murray, was well known among the county’s many Southern sympathizers for how she had fought her own Civil War during the 1860s.

According to family history, Union soldiers had threatened Elvira with hanging after some of them – who had stolen a cow from the Murray property and slaughtered it – grew ill after eating the meat that Elvira had ordered her enslaved persons to poison in retribution.

She escaped the hanging, Weagley said, only after a Union officer recognized her as the mother of “Plunk” Murray, a follower of “Bloody” Bill Anderson, the Southern-sympathizing guerrilla leader.

Plunk, apparently, had chosen to aid this same Union officer in a moment of need, prompting the officer’s own merciful act.

In 1904 builders of the Confederate monument in Fairview Cemetery invited his great-great grandmother to help dedicate it, Weagley said.

Since his retirement from teaching in 2016, Weagley said he has grown less reticent about detailing how the 19th century attitudes held by his ancestors could manifest themselves in the 20th century.

A member of Clay Countians for Inclusion, whose members believe the Confederate statue should be relocated from Fairview Cemetery, he described in a recent letter to the Liberty City Council how Elvira became the grandmother of Pearl Davidson who, by the middle the 20th century, was providing daycare for a young grandson – himself, the now-retired Robert Weagley.

Pearl, Weagley said, was an admirer of Elvira and shared many of her sentiments.

“She was always telling me to avoid Black people and not to touch them,” Weagley said.

In his letter to council members, Weagley described the family row that occurred in 1968 when he, then 16 years old, invited a Black high school friend to spend the night in the family guest room – the same room used by Pearl Davidson when she visited.

When his grandmother learned of this she confronted Weagley, threatening to disown him, prompting Weagley to tell her to go ahead.

When she died several weeks later, Weagley said, his mother accused him of hastening his grandmother’s death.

More than 50 years later, Weagley sponsored a matching grant for the new memorial that has since raised about $45,000.

Weagley takes mild exception to the word “reparation” in regards to his contributions.

“I don’t think this represents ‘reparation,’ ” he said.

“This is a drop in the bucket compared to the economic damage done to the African American population following the abolishment of slavery.”

But his contributions represent his attempt to do the right thing, he added.

“I have the means to help with this,” Weagley said.

“I have a desire, just as an individual, to try to move us forward as a species as best I can, in the little things I can do.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.