Kansas Last in Nation on Mental Health Ranking Lack of Support for Services, Consequences of Pandemic

Published March 1st, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Cover photo from the 2023 State of Mental Health in America. (Courtesy | Mental Health America)For a few years, K. Johnson and her husband were able to cobble together behavioral health services for their daughter. After the young girl experienced trauma in fifth grade, therapy kept her relatively stable. But about three years ago, she went to Marillac for a mental health emergency and quickly ran out of options for care.

“My husband works for the county, so we have pretty good health insurance. But when I called to find out what resources were available (for inpatient treatment) Blue Cross said they don’t offer that benefit,” Johnson said.

The insurance company did inform her about state-funded waivers for Medicaid that pay for residential treatment and outpatient care for children who are seriously emotionally disturbed (SED waivers). After qualifying, their daughter has since spent time in facilities in Newton and Topeka.

“Those places are so expensive, when I asked about private pay, they said, ‘We don’t have anyone do that,’” she said. “They told me we’d have to take out a second mortgage on our house or use our 401(k).”

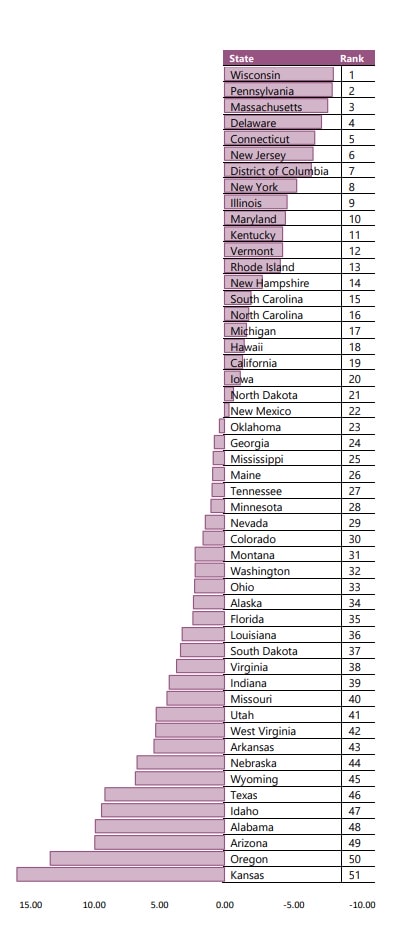

Although finding mental health care, whether inpatient or outpatient, is challenging anywhere, a recent report found that Kansas ranks lowest of all states for mental health care. (Missouri ranked 39th.)

The annual State of Mental Health in America report, released late last year, found that Kansas not only had a higher prevalence of who reported mental health issues, but the state ranked low on access to care for people needing treatment, particularly among youth with severe behavioral health challenges. A decade of low funding and a dearth of providers are the main culprits behind the state’s issues.

Why Kansas?

The report, released by Mental Health America, is based on data from 2019 and 2020, so it included data from early in the COVID-19 pandemic, said Maddy Reinert, senior director of population health at the organization. Fifteen measures are used, including youth and adults with substance use disorders, people with mental health conditions who did not receive treatment, workforce sufficiency and the number of people whose insurance doesn’t cover behavioral health care.

Reinert said several factors accounted for Kansas’ low ranking. The state ranked second-to-last in the prevalence of mental health conditions, and last for youth with a substance use disorder (9% vs. the national average of 6%). There are also a high number of adults reporting serious thoughts of suicide (6.44% vs. the national average of 4.84%).

Kansas also ranked low on access measures, particularly for youth with depressive disorder getting consistent treatment. Kansas ranked lowest in the nation here, with only 6.5% receiving needed care as opposed to the national average of 28%. Mental Health America equated consistent treatment with at least seven visits in a year.

Kansas is not alone in its demand for care and lack of access, but it still ranked lower than other states grappling with the same issues. Providers in the industry tend to point to Kansas’ large swaths of rural communities and difficulty attracting behavioral health providers to explain the low rankings.

But Eric Litwiller, director of development and communications at the Mental Health Association of South Central Kansas, said these are merely excuses.

“Kansas has been ranked low, at 46 or 47 for some time, and people say it’s because we are rural and have no practitioners,” he said. “People have to drive hours to get to a town with a therapist and we know that that’s true. But that happens in other states, too. Our spending per capita is low, but it is in other states, too. There are states with more of those issues than us and they ranked better. When you are last in the country, those excuses go out the window.”

Litwiller did acknowledge that, especially in rural areas, people don’t seek treatment because they think they just must “tough it out.” And in some areas of Western Kansas, there just aren’t any providers, even if people wanted to seek help.

Sarah Berens, executive director of Camber Children’s Mental Health in Hays, said there is a big rural population that struggles with the stigma of asking for help. Some of her clients in rural communities also have lower incomes or lack transportation, both barriers to getting help. Internet connections also may be unreliable, or they can’t afford service, meaning they can’t even access telehealth services.

“Also, if someone is extremely depressed, they may not even have the ability to get out of bed, so that factors in as well,” Berens said. “It’s a combination of so many different things to tackle because each of these factors can feel like they are very acute.”

Workforce Challenges

Litwiller said the single biggest issue in Kansas is lack of clinicians.

“If you call any mental health organization in the state for something as simple as an outpatient counseling appointment, you will more than likely get a three- to four-week lead time at a minimum,” he said. “That’s a clear sign that we don’t have clinicians available, and someone going through a crisis doesn’t have a month to wait to see a therapist.”

Litwiller’s organization has nearly 200 staff and serves about 10,000 people annually – substantial for a nonprofit behavioral health provider. Still, they don’t have sufficient local staff to care for all the youth in need of services. They contract with a pediatric mental health professional based in Hawaii for many clients.

“The fact was, the specialist in Hawaii was the closest and best we could find,” he said.

“There are states with more of those issues than us and they ranked better. When you are last in the country, those excuses go out the window.”

Eric Litwiller, director of development and communications at the Mental Health Association of South Central Kansas

High Plains Mental Health Center in Hays has been offering to help current staff with bachelor’s degrees get a master’s at Fort Hays State University, said Dave Anderson, High Plains’ director of clinical programs. They have five current staffers in the pipeline for a master’s, which is resource intensive. To help students get through the program, they perform students’ internships and allow them to use some of their normal 40 hours of work as practicum time.

“If we can find people that have a passion to do this work and already have roots here, we think we are going to be more likely to keep them as employees than trying to draw someone out of grad school to Northwest Kansas,” he said.

Funding has also been a challenge for staffing for much of the 2000s in Kansas.

“Community mental health centers have been underfunded for so long, and the pay was so poor, it’s been hard to attract people who are getting debt from grad school into a profession that didn’t pay well,” Anderson said.

Cuts to the public mental health system in Kansas began about 2012, according to Tim DeWeese, director of the Johnson County Mental Health Center. He said his organization has seen about a 70% reduction in state grants since then.

“We experienced almost a decade-long dismantling of the system, and we are now seeing the results of that,” he said.

His organization can serve about half of the existing needs in Johnson County. He said that about 2% of adults and 5% of kids have an emotional disturbance or substance use disorder in the county. That totals about 18,000 that could benefit from intensive community-based services, and they serve about 10,000 people a year.

Mental Health in America

Patchwork Service

Another major issue for mental health care, in general, is an incohesive private system.

“If you fall and break your ankle, you go to emergency care; and if it’s really bad, to the hospital,” Litwiller said. “And most people can list off three or four of those near their homes. In the case of a mental health emergency, even if people knew how to navigate the system, the facilities don’t exist.”

Johnson found this out when she was seeking care for her daughter. They had a private therapist for years and received therapy through the Olathe School District and Sunflower House. Some treatment was free, and some was paid before they needed the SED waiver for more intensive help.

“One of the biggest obstacles for our daughter was finding a therapist,” she said. “Everyone touted our EAP (employee assistance program). But you get eight free sessions and about 90% of the time the person doesn’t even take your insurance after that.”

They had a difficult time finding anyone who was reasonably close to home, took new clients, was available for after-school hours, accepted their insurance and charged a reasonable rate.

“It was very challenging to find someone who fit all of those buckets,” she said.

Ann D.’s daughter has been in therapy for emotional dysregulation for about eight years. She also said finding good therapists and psychiatrists in Johnson County has always been a challenge. During the pandemic, her daughter’s condition became more severe, resulting in calls to the police to help de-escalate the situation.

After one of these house calls, the officer told the family about services at Johnson County Mental Health and the SED waiver. Ann had assumed she and her husband made too much money to qualify. But finances aren’t the only factor accounted for in the application. Receiving the waiver opened a whole new world for them, she said.

Once in the public system, they received services they couldn’t in the private sector, including a case manager, respite care, a parent support specialist and a 24-hour crisis line that their daughter used when needed.

“Being on those services was a very, very empowering process for everyone,” she said. “The biggest difference was the coordination of care. Our daughter had a therapist, a psychiatrist and she had been in a few group situations, but none of those people were talking to each other.”

Moving the Needle

Providers in the state who understand their populations can use resources wisely to improve access.

Along with its long-term treatment, Camber is planning to add acute services. In smaller towns, community mental health centers are a main resource, but they, and local emergency rooms, aren’t equipped to handle someone in a behavioral health crisis, Berens said.

Their long-term facility houses 18 beds, and they’ll soon have 14 acute-care beds, where youth can stay five days to a week to stabilize and return home. They treat youth across the state but several of the new beds will be earmarked for people from western Kansas, where these services aren’t otherwise available.

“We’ve seen an increase in youth suicide attempts since the pandemic here and nationally,” she said. “We wanted to bring these kinds of beds here because we’ll be able to reach over 600 more clients a year.”

“We’ve seen an increase in youth suicide attempts since the pandemic here and nationally.”

Sarah Berens, executive director of Camber Children’s Mental Health in Hays, Kansas

DeWeese said alcohol misuse among youth has become more prevalent, as has the use of fentanyl, which he has seen double since the pandemic. They have an inpatient treatment facility, which always has a waiting list. But they also started an outpatient program for youth with substance use issues. It was there that they were seeing the greatest growth in recent years. They are adding 21 new staff positions to expand their services.

Aside from growth in kids in need, they created the program because most of the youth who ran away from their residential program were from Johnson County. It’s a lot easier for them to get back home or stay with friends than someone from Garden City or Great Bend.

“We hoped that an intensive outpatient treatment for Johnson County kids would help them stay in treatment longer,” he said.

Telehealth has also helped providers expand their services. Anderson said they are short of staff and have about 10 providers they contract with to provide telehealth services.

“Without access to that service we would really be struggling – more than we already are – to meet community needs,” he said.

The Mental Health Association of South Central Kansas offers a self-screening tool for depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. In 2020, the use of that tool skyrocketed 650% for people wondering about anxiety and 900% for depression, Litwiller said.

“People had the ability to find out if what they were feeling was normal or might point to a bigger issue that merited professional attention in the privacy of their own home,” he said.

Reinert said attacking the issue of behavioral health prevalence is challenging, but research points to ways to keep the condition from worsening.

Early intervention is one way. Increasing mental health services in schools helps reduce the stigma of seeking services and can help prevent the condition from reaching a point of crisis later in life, she said.

She also advocates for working to address social determinants of health – including people’s economic conditions, education access and living environment. For instance, she said income inequality at the state level is associated with high rates of depression. And factors that can affect suicide risk for adults include elevated levels of community violence, financial hardship and lack of access to health care.

Medicaid expansion also goes a long way to improving access to care because it is the largest payer of public mental health services, Reinert said. She said expansion reduces disparities for Black and Hispanic adults as well as the number of adults who delay care because of cost.

“This one indicator makes a big difference,” she said. “When we see states expand Medicaid, over time the number of adults with mental illness who are uninsured drops, and we see states moving up in our rankings pretty consistently.”

Even in Kansas, the pandemic highlighted the need for mental health services and the state responded. Since 2021, state funding has increased, and legislation was passed that should increase access.

“I was reading the (Mental Health America) report and thinking of the work the state has been doing in the past several years,” Anderson said. “And I have no doubt that when the new report comes out, Kansas will look more favorable in terms of the provisions that are offered.”

Tammy Worth is a freelance journalist based in Blue Springs, Missouri.