Getting Off the Grid, Living as Our ‘Best Selves’ A Community in Rural Missouri Seeks A More Sustainable Future

Published October 19th, 2022 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: John Bambrick-Rust tries to include his children in as many tasks on the homestead as possible. (Cami Koons | Flatland)ADAIR COUNTY, Missouri – “Get up girls,” Regina Bambrick-Rust called and then clicked with her mouth.

Her two horses resumed their march as Bambrick-Rust continued feeding laundry through her old school washing machines.

It’s a common household chore, but few families choose to do their laundry with actual horsepower.

It’s just one of the ways the Bambrick-Rust family tries to be sustainable on their homestead in northeast Missouri.

Together with several other families, they make up the Bear Creek Community Land Trust, an off-grid community designed for a lasting planet.

Flatland on YouTube

What is Off-Grid Living?

An off-grid lifestyle prioritizes self sufficiency, so homesteads are not connected to traditional utilities (the grid) such as electricity and water.

Many homesteads generate electricity for small household appliances, or things like an electric chicken fence, via solar panels.

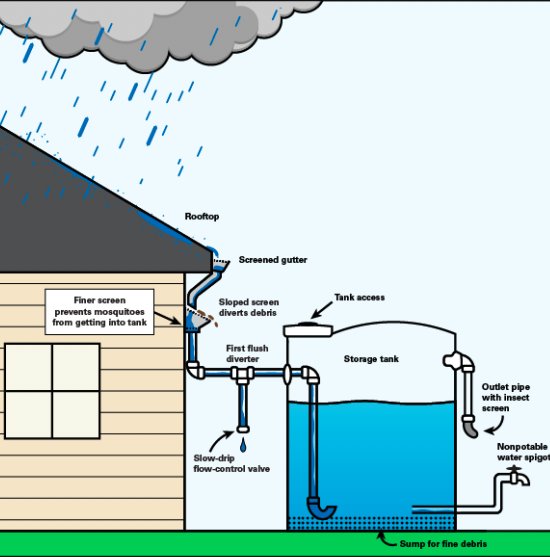

Their water comes from a cistern, which holds rainwater harvested from the roof.

Conservation is also a big component of an off-grid home.

Kelly Pott is a Bear Creek leaseholder, who is still in the process of transitioning her family from St. Louis to living full time at the homestead.

The Pott household is currently connected to county water, but they use it sparingly. She hasn’t paid more than $20 on a monthly water bill at the house.

They use a composting toilet, an outdoor shower in the summer months and take cup baths in the winter.

“It’s real cold,” Pott laughed. “But it works. You get clean.”

Most cooking is done in wood stoves or propane camping burners.

There’s a lot to get done on a homestead.

“We use machines,” Bambrick-Rust explained. “But I enjoy working with the horses more.”

Holistically, she likes using hand tools and doing things without machinery. But it’s not feasible to do it all that way.

“You can’t do everything,” Bambrick-Rust said. “You have to choose which things you’re going to take on, or which things are really important to you.

“Sometimes we’re adopting technologies that hopefully, in some future generation, we can get off of,” she said and smiled at 8-year-old Johanna standing next to her.

In addition to conserving resources, the homesteads try to grow as much of their own food as possible.

Most houses have a flourishing garden, fruit trees throughout the property, trails for mushroom foraging and a chicken coop.

The Bear Creek Community Land Trust is small in numbers now, but hopes to soon grow large enough to graze livestock.

The folks at Bear Creek aren’t pursuing their dreams in isolation. According to 2020 research by Big Rentz, an estimated 250,000 people live off the grid in the United States.

More narrowly, the Center for CLT Innovation currently lists 302 community land trusts in the U.S., nearly double the number in 2006. In 2018, Grounded Solutions Network estimated that there were about 12,000 homeownership units in community land trusts nationwide.

Tracking Community Land Trusts

Origins of the Land Trust

Members of the 184-acre Bear Creek community southeast of Kirksville lease their land, for the span of a lifetime, from the land trust in an effort to prioritize stewardship of the land over ownership.

Julia Jack-Scott bought her land more than a decade ago, prior to the formation of the land trust.

She, like many of the founding members, came out to the area because of the nearby Possibility Alliance, which has since closed.

The Possibility Alliance, started by Ethan and Sarah Hughes, was described in a 2011 article in Mother Earth News as an education homestead. It was open to all who wanted to come and learn about this type of lifestyle.

The alliance drew visitors from all over, and some started buying the nearby land. They wanted to live with the same off-grid and self-sustaining practices.

“They were all just good neighbors at that point,” Jack-Scott said.

As folks started to leave and others wanted to move into the community, it became clear that some sort of structure was needed. Until that point, Jack-Scott said, it was a lot of handshake agreements and unclear property lines.

They drew inspiration for the land trust from the group’s sister community, Red Earth Farms in Rutledge, Missouri, which had already created a lot of the documents and community guidelines that Bear Creek employs.

“We’re in some ways borrowing from them and changing it a little bit to also allow for some communally owned land and structures within Bear Creek,” Jack-Scott said.

The Bear Creek Community Land Trust has four leaseholders, several more for sale and designated community land. It hosts visitors interested in learning, needing a place to stay or seeking a digital detox.

A formal structure allows the community to host visitors and function properly, but John Bambrick-Rust said managing the structure is just a small small part of what they do.

“It (the land trust) is trying to lead us away from personal ownership, that it’s not our land,” he said. “I believe it’s God’s land and we’re called to be a good steward of it. … The land trust structure helps you lean in that direction a little more.

“This is land, we’re here and we’re going to steward it. But we’re stewarding it to pass it on to the next generation with sustainable practices.”

Why Live On the Land?

It’s easy to romanticize the lifestyle.

But living off the grid, while it fosters a deep connection to nature and between community members, is not without struggles.

The Jack-Scott family lives in a beautiful home constructed around walls of straw bales. It took her four years of sleeping in a tent, clearing trees and mixing natural plaster from Missouri clay and sand to complete her dream home.

She has a closer connection to the structure than most people do with their houses, but it can also be frustrating.

For example, the pipes running from her cistern into the house will freeze in the winter. The wood frame swells in the warm summer months, and this summer she lost several chickens to a hungry raccoon.

“There just isn’t that convenience (or) comfort,” Jack-Scott said. “Hit a switch or call somebody to make this work. When it breaks it’s more of a complex system that we have to be participants in.”

Even after 11 years of living on the land, Jack-Scott is still learning new skills.

“I enjoy that process,” Jack-Scott said. “The constant learning curve there is to living out here.”

“It’s been very nice to have a space where we can unplug. Electronics are still a part of their lives … but they don’t reach for them as much here … they reach for each other.”

Kelly Pott, a Bear Creek Community Land Trust leaseholder

Despite the hardships they choose to live under, each family noted that they find themselves more at peace, and more connected to the tasks at hand.

Pott described how simple chores like dishes or laundry become moments of quiet meditation, or quality conversation if her teenage boys are helping her.

Electronics aren’t outlawed, but Pott said they end up on the shelves when the family is out at the land trust. Rather than separate or sit around a TV, Pott said most days end with a board game or seated around the table as family.

“It’s been very nice to have a space where we can unplug,” Pott said. “Electronics are still a part of their lives … but they don’t reach for them as much here … they reach for each other.”

Away from modern distractions, community members try to be intentional about how they spend their time.

John Bambrick-Rust said outdoors is where most of them feel like they are living to be their “best selves,” so they built outdoor kitchens and dining areas.

“At our deepest, best self, that’s what we’re trying to do,” John said. “It’s our attempt to try and find that better world for ourselves and for our children.”

Dominic, Bambrick-Rust’s 2 1/2-year-old son, munched on a green pepper he had silently picked while his dad walked about the garden.

John Bambrick-Rust smiled at the sight. He grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. At 2 years old, he had no idea how to garden or forage for his own food, but here he sees his children grow up with these skills.

He sees it as a sign that the next generation will be even better stewards of the land.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.