If at first your experiment gets blown up in a rocket, try, try again

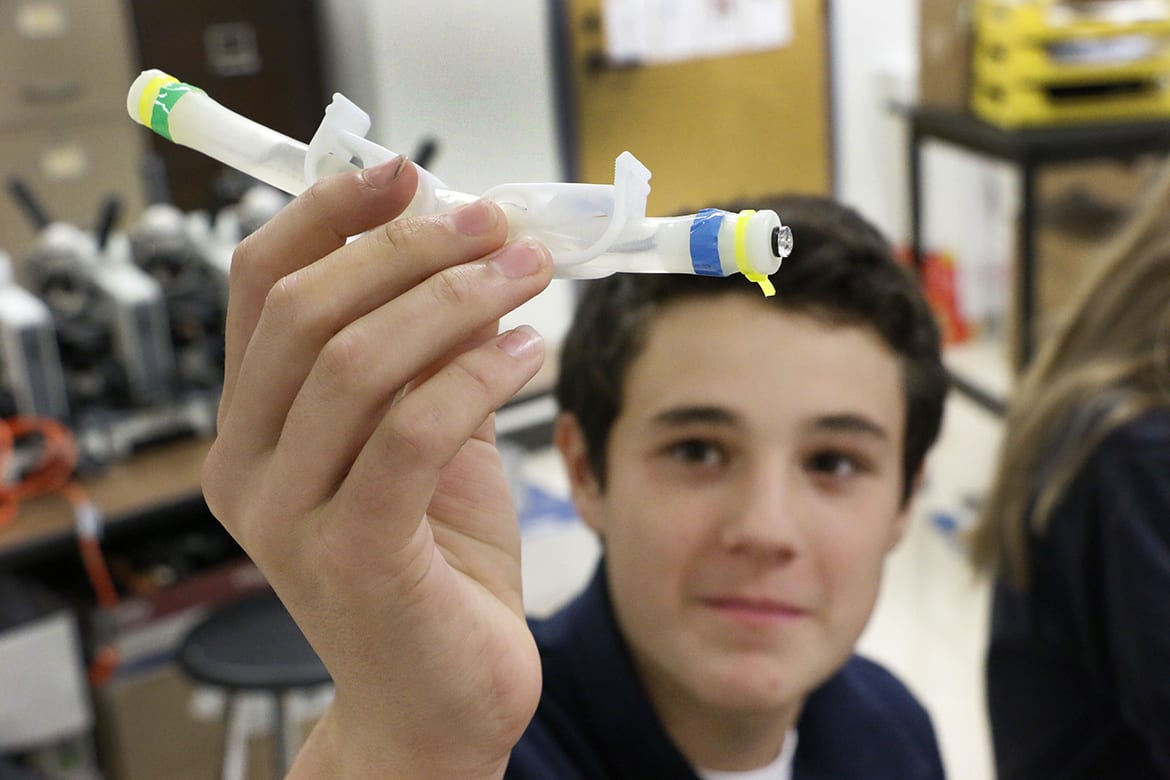

Holden O'Keefe holds up a finished Fluids Mixing Enclosure or FME that contains an experiment to measure the effectiveness of iodine in microgravity. (Photo by Lindsey Foat / The Hale Center for Journalism)

Holden O'Keefe holds up a finished Fluids Mixing Enclosure or FME that contains an experiment to measure the effectiveness of iodine in microgravity. (Photo by Lindsey Foat / The Hale Center for Journalism)

Published November 24th, 2014 at 10:56 AM

Sitting at a lab table over the lunch hour at St. Peter’s School in Kansas City, Missouri, a group of eighth graders are loading freeze dried E.coli bacteria into plastic tubes. It’s all part of a special package destined for the International Space Station.

And it’s not the first time students Holden O’Keefe, Eamon Shaw and Nicole Ficklin have tackled this process. Just three weeks ago, their work was lost when the unmanned rocket carrying 19 student experiments and 5,000 pounds of equipment for the ISS exploded just after liftoff.

These young scientists now have a second chance at testing bacteria growth in microgravity. It’s all part of the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program (SSEP).

“We were just kind of frozen in shock for a couple seconds and we just burst out talking, asking how and why did this happen,” said Ficklin of her teammates and others that had gathered across the street at Benjamin Banneker Charter Academy of Technology to watch the launch on Oct. 28, 2014.

“Of all of the things that could have gone wrong that was kind of the one thing that we weren’t expecting.”

St. Peter’s SSEP coordinator and science teacher Bob Jacobsen was also at Banneker and said it brought back memories of seeing the Challenger explosion as he watched with students 27 years ago. Many classrooms were watching that day in 1986, as it was the first flight involving NASA’s Teacher in Space Project, to which Jacobsen himself had applied.

“Fortunately [with this explosion] no one was hurt,” Jacobsen said. “But I was very, very disappointed because I know how much time and effort they had put into their research and putting together their lab.”

At the same time, Jacobsen said that the explosion also provided a lesson about real-life science, including the risks and setbacks.

Fortunately for the students, another launch, this time with the company SpaceX, is scheduled for December 16.

Using a flexible tube with clamps to create three compartments with different substances, the students’ experiment will test how E.coli responds to the antiseptic iodine in a microgravity environment.

Nicole Ficklin (left) and Eamon Shaw pipette Glutaraldehyde into one of the tube’s compartments. This liquid will “freeze” any bacteria growth before the experiment returns to earth from the ISS. (Photo by Lindsey Foat / The Hale Center for Journalism)

“We had to submit a real proposal with real restrictions,” Shaw said, “We have a tube that’s only 10 milliliters that we have to fit an entire experiment in, like that’s crazy!”

After the experiment arrives at the ISS, the astronauts will unclamp each compartment at a scheduled time so that the students can carry out the same steps on earth.

“That’s the great part about (SSEP) … you’re a real scientist when you’re doing this,” Shaw said.

The students say the results of the experiment could also have real impact on the astronauts.

“The United States uses liquid iodine to rid their water of bacteria on the ISS,” Ficklin said. “So if it eliminates less bacteria in space they might need to find a more effective antibacterial agent so that people won’t get sick.”

Shaw, O’Keefe and Ficklin began researching and creating an experiment proposal last spring.

The students are using three FME’s as part of the experiment. One will go to the ISS, while the other two will measure E.coli’s response to iodine on earth and E.coli growth without any iodine. (Photo by Lindsey Foat / The Hale Center for Journalism)

After their experiment was selected to go to the space station, they shared their proposal at a conference at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. last July.

“We presented on the same stage that Neil Armstrong and some presidents have presented on,” Shaw said.

In the year or so since schools in Kansas City became part of SSEP, more than 2000 area students have participated in the program, and three teams have had their experiments selected by NASA to go to space.

William Wells is the SSEP KC Program Director, and says that Kansas City’s community approach to the program is unique among the 99 communities that have participated since it was created by National Center for Earth and Space Science Education (NCESSE) and the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education in 2010.

In most communities, SSEP is coordinated within one school district, but students from eight different schools and backgrounds have the opportunity to compete and collaborate.

“It’s a program that’s built upon breaking down silos, so that the students learn and share with others,” Wells said. “If you are able to ask and explore with those who are different from you … it helps us find answers that serve everybody.”

While students in fifth through eighth grade propose experiments, those in first through eight grade are invited to design mission patches.

Local students also lost mission patch designs that were on the rocket that exploded on Oct. 28, 2014. (Images courtesy of William Wells)

Wells said three patches designed by local students were lost in the October 28 rocket explosion. The originals, of course, are gone, so photocopies of the designs will be sent to Houston as part of the relaunch.

Prior to FedExing their experiment to Houston so that it can be approved and loaded onto the rocket, the three young scientists huddled together.

“Touching space,” they each say, carefully passing around the small tube, and repeating: “Touching space.”