English Language Learners: How Your State Is Doing

Published February 25th, 2017 at 6:00 AM

About 1 out of every 10 public school students in the United States right now is learning to speak English. They’re called ELLs, for “English Language Learners.”

There are nearly 5 million of them, and educating them — in English and all the other subjects and skills they’ll need — is one of the biggest challenges in U.S. public education today.

As part of our reporting project, 5 Million Voices, we set out to gather up all the data and information we could find about who these students are and how they’re being taught. Here’s our snapshot:

The vast majority — some 3.8 million ELL students — speak Spanish. But there are lots of other languages too, including Chinese (Cantonese and Mandarin), Arabic and Vietnamese.

Most ELLs were born in the United States, and are U.S. citizens.

The state with the most ELL students is California — which has 29 percent of all ELLs nationwide. Texas has 18 percent, followed by Florida with 5 percent and New York with 4 percent.

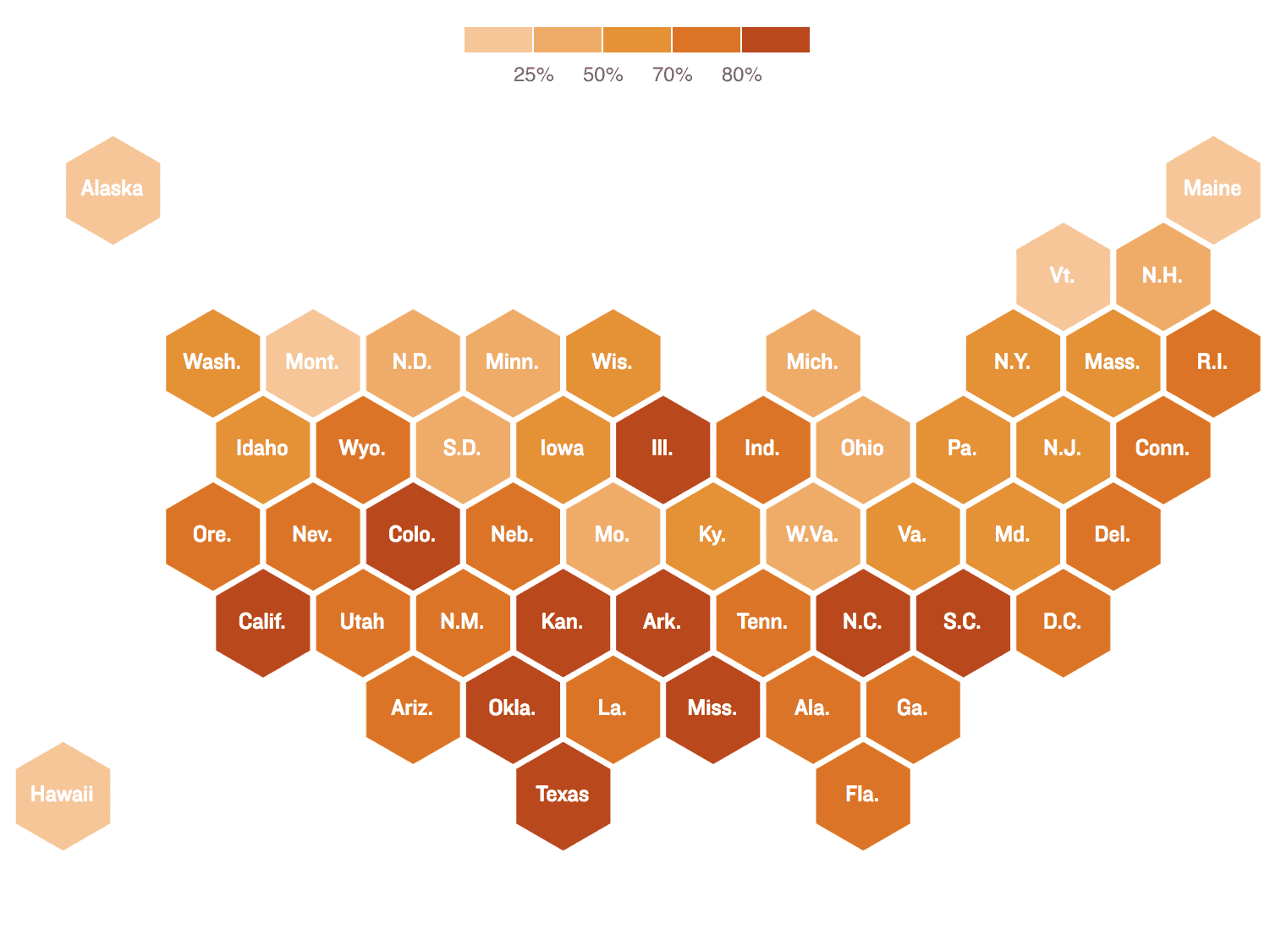

From 2000 to 2014, the growth of the ELL population was greatest in Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina.

Based on the most recent data available, NPR found that no matter where they go to school, most ELLs are struggling because they have little or no access to quality instruction tailored to their needs. Although 90 percent of these kids are enrolled in designated ELL programs, at least one recent study argues that the quality of these programs is suspect.

Funding for ELL programs comes almost entirely from local and state sources. That’s because federal education funding on average represents about 11 percent of what local school districts spend overall.

Still, the U.S. Education Department does focus on how ELLs are treated. The department’s Office of Civil Rights has singled out 121 school districts in which not a single student is even enrolled in an ELL program. Overall, as many as half a million do not receive any special instruction to learn English.

Identifying ELL students

Identifying and screening ELLs is tricky. In most states, school districts use the simplest and lowest-cost method: a take-home survey. An overview of how the screening differs state-to-state can be found here.

In districts with large ELL populations, schools typically test students to determine how much English they speak, read and write. This allows teachers to pinpoint their needs.

Take, for example, a 12-year-old who still can’t read in English. Rather than placing that student into a first- or second-grade class with much younger kids who are learning to read, that 12-year old is placed with her peers in sixth or seventh grade, but is pulled out for intense English instruction.

Another option is transitional bilingual instruction. In this model, a teacher who is fluent in both English and the student’s native language builds on that child’s language for at least 2-3 years. The goal is having the student become fluent in both English while retaining a native language.

A third option is “dual-language immersion,” which requires that a classroom be made up of both ELLs and native English speakers. In this approach, all subjects are taught in two languages during the school day. English speakers learn a second language and ELLs learn English. The demand for dual language immersion has grown significantly in recent years.

Achievement

As a whole, English language learners still lag behind in terms of academic achievement.

Most are not making the transition to English quickly enough. Many ELLs remain stuck in academically segregated programs where they fall behind in basic subjects.

Only 63 percent of ELLs graduate from high school, compared with the overall national rate of 82 percent.

In New York State, for example, the overall high school graduation rate is about 78 percent. But for ELLs, it’s 37 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Of those who do graduate, only 1.4 percent take college entrance exams like the SAT and ACT.

Teacher shortages

ELLs are often concentrated in low-performing schools with untrained or poorly trained teachers. The shortage of teachers who can work with this population is a big problem in a growing number of states.

Gifted ELLs

Only 2 percent of ELLs are enrolled in gifted programs, compared with 7.3 percent of gifted non-ELL students.

According to the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), a gifted ELL student is likely to know much of the curriculum content on the very first day of school. But NAGC researchers have found that most gifted ELLs are not on anybody’s radar.

Researchers say that, even when ELL students are identified as gifted, the impulse is often to keep them out of accelerated programs despite evidence that they would benefit from more challenging work while they’re learning English.

In his book, Failing Our Brightest Kids: The Global Challenge of Educating High-Ability Students, Chester E. Finn Jr. argues that school policies for identifying gifted ELLs are inadequate. Finn, a former assistant secretary of education, says schools need to train teachers to be more like talent scouts, so that they can spot gifted ELLs.

Otherwise, says Finn, “We’re losing talented kids from immigrant families who don’t know their way around the American system.”

9(MDA1MjcyMDE0MDEyNzUzOTU1NTMzNmE5NQ010))