Drought Sapping Fisheries and Marshes in Missouri and Kansas 'It All Comes Down to Mother Nature. We Need Rain.'

Published August 3rd, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Cheyenne Bottoms, a nationally known wetlands area in central Kansas, was high and dry in late May. It has recovered somewhat after rains in June and July, but it is still thirsting for water. (Brent Frazee | Flatland)Johnny Everhart gets a stark reminder of the ongoing drought every time he walks to the banks of a creek that meanders through his land in west-central Missouri.

In good years, Honey Creek is deep enough to support crappies, channel catfish and even a few big blue cats. But after months of dry weather and blistering heat, there are only a few puddles in places.

“It’s just depressing,” said Everhart, who has fished the creek for 58 years. “This is the driest I’ve ever seen it.”

Even a few recent rains haven’t changed the situation. It’s just “bone-dry,” as he puts it, in his part of Missouri.

“We might get a half-inch of rain or so,” he said. “But the next day, you can kick up dust.”

And the worst might not be over.

Everhart relies on small creeks to fill his duck marshes each fall in anticipation of the waterfowl hunting seasons. But he and many others need much more rain to buoy their hopes.

Many others in Missouri and Kansas share Everhart’s pain.

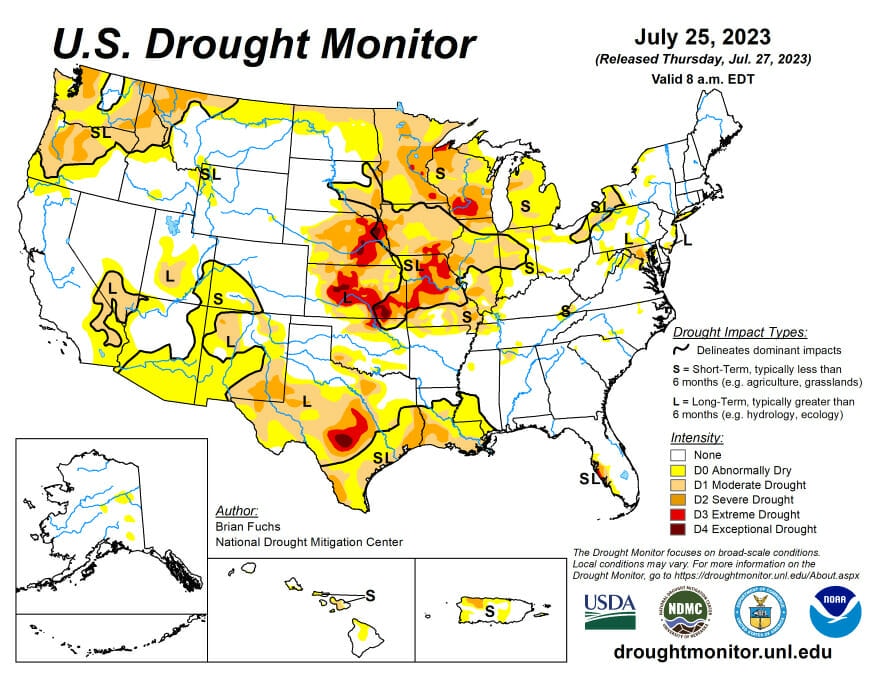

In the second year of a relentless drought, the Mo-Kan area is among the driest places in the nation. Look at the latest U.S. Drought Monitor, and you’ll see a splash of color in Missouri and Kansas. That’s not good. The areas shaded in brown, red, orange and yellow show the spots hardest hit by the drought. And there are plenty of them in the two states.

While farmers and ranchers fret about the drought’s effects on crops and livestock, anglers and hunters in some spots are also watching outdoor recreation literally dry up.

Small bodies of water such as farm ponds or state fishing lakes have either gone dry or are critically low. Parched, crack soil is prevalent at famous waterfowl marshes such as Cheyenne Bottoms in central Kansas. Boat ramps are unusable at many small reservoirs in western Kansas. And wildlife such as pheasants are struggling after poor nesting conditions in the spring.

Luckily, those conditions aren’t statewide in either Missouri or Kansas. Timely rains in June and July recharged small bodies of water and improved public waterfowl marshes thirsting for water in some parts of the states.

But it’s been strikingly spotty. Rainfall amounts can vary drastically even within the same county, wildlife officials say.

Even in the areas where the rain provided limited relief, much more is needed. The Drought Monitor shows that much of the two-state area is still rated from abnormally dry to exceptional drought.

“The drought is taking its toll,” said Monte Manbeck, manager of the Neosho Wildlife Area, a well-known waterfowl area in southeast Kansas. “In the month of July, we’ve had a little more than an inch of rain. That’s not much, but it’s more than we’ve had in some time.

“We just need more.”

Disappearing Fisheries

Ford State Fishing Lake near Dodge City, Kansas, might well be the poster child for the drought of 2022-2023.

Before the drought set in, fisheries biologists with the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks surveyed the small body of water in southwest Kansas and found an impressive population of bass.

“Ford had water for five or six years since the last time it went dry and the largemouth population just boomed,” said Lowell Aberson of Wildlife and Parks. “We had a bunch of bass in the 5- to 6-pound range, and we sampled one that was over 7 pounds.

“It had to be the best small-water public lake for bass in the state.”

Then the drought set in. The 48-acre reservoir steadily shrank, a blue-green algae outbreak occurred and a major bass die-off followed.

“Most of those big bass died,” Aberson said. “It was depressing as heck.”

Aberson has learned to expect such drastic swings in southwest Kansas, where he serves as the fisheries biologist for Wildlife and Parks.

The arid region doesn’t have many public fishing sites to start with. When a prolonged drought sets in, the few fishing lakes tend to suffer.

“I’ve been out here in western Kansas for almost 30 years, and I’ve seen times when some of these small bodies of water have been bone dry,” he said. “We’re not there yet, but we’re hurting.

“Who knows what they will look like by the end of summer?”

Suffering Waterfowl Marshes

In the spring, the Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area in central Kansas looked like a giant desert.

Amid a second year of drought, the largest inland wetland in the United States was completely dry, save for a few scattered puddles.

The situation has improved somewhat since then, thanks to several rains in July. But the situation is still dire, with more hot and dry weather predicted.

With no pumping capabilities, the bottoms are reliant on runoff from area rivers and creeks. When they suffer, the wetlands suffer.

“We didn’t have any water to speak of in our marshes for almost a year,” said Jason Wagner, manager of Cheyenne Bottoms, a Wildlife and Parks public wetlands. “We went dry the end of June last year and didn’t get water back until late May of this year.”

After unexpected rains in June and July, there is limited water in some of the wetlands. But much more is needed before the fall migration begins.

“When it gets to 100 degrees and the wind blows, we can lose from a half-inch to an inch of water a day to evaporation,” Wagner said. “So, we still need a lot more rain.”

This isn’t the first time Cheyenne Bottoms has been struck by a major drought.

“We’ve been in what seems like a 10-year cycle,” Wagner said.

But the area always bounces back, bigger and better than ever. That’s why Wagner remains cautiously optimistic.

“In 2018, we had been dry for a long time, then we got some heavy rain on Labor Day weekend,” Wagner said. “It changed conditions almost overnight.

“We had water in our pools, and we got a lot of ducks migrating in. We need something like that to happen this year.”

Drought Waiting Game

Manbeck at the Neosho Wildlife Area is similarly hopeful that things will turn around.

Neosho’s wetlands also have been severely affected by the drought. But recent rains have raised water levels in the Neosho River to the point where Manbeck and his staff have been able to pump water into the marshes again.

That pumping has been mostly to irrigate moist-soil plants — key food for migrating ducks — that have sprouted in the dry basins.

But Manbeck hopes that more rain will arrive in time for wildlife area workers to pump water into the marshes before the fall waterfowl migration takes place.

“I’m still worried that we’ll have enough water in the river to pump this fall,” he said. “We need some more timely rain.”

The situation is getting better.

Only two swatches of Kansas counties — one in west-central, the other in the southeast — remain in “exceptional drought,” according to the latest Drought Monitor.

In Missouri, the situation in central Missouri, which was in the “exceptional drought” category, has improved, though it and other regions are still in “extreme drought.”

Still, there’s no denying that the dry weather has taken its toll. Many landowners have lost their ponds to the extended dry conditions.

Everhart sees the results in his part of the world.

“The dozers have been busy around here,” he said. “Landowners are either digging their ponds that went dry deeper or building new ones.

“But when it’s this dry, it all comes down to Mother Nature. We need rain.”

Brent Frazee is an award-winning writer and photographer who served as the outdoors editor of The Kansas City Star for 36 years before retiring in 2016. He lives in Parkville with his wife Jana and his two Labrador retrievers, Millie and Maggie.