Driving While High: Difficult to Measure, Harder to Enforce When it Comes to Marijuana, There Are Cracks in the Legal System

Published November 3rd, 2022 at 6:00 AM

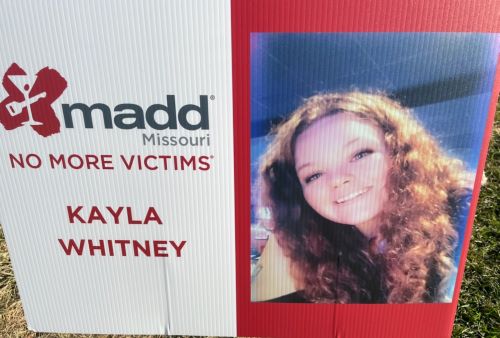

Above image credit: Passenger Kayla Whitney died when this 1996 Mustang slammed into a light pole on Oct. 11, 2021. (Contributed)Fear lingered on her deceased daughter’s face.

Anna Hixon tried to touch up her “baby girl’s” makeup before the funeral. She wanted her skin tone to appear natural, the ivory hue of Kayla Whitney before she died at 22.

On Oct. 11, 2021, the car her daughter was riding in slammed into a light pole in Kansas City.

“She was scared,” Hixon said of her final memories of her daughter’s expression. “That’s how her face looked.”

The now 19-year-old driver was her daughter’s boyfriend.

Witnesses told police that he desperately tried to revive Kayla. He was later treated at a hospital for a bruised lung and abrasions.

Medical records subpoenaed by Kansas City police also showed that he tested positive for cannabinoids when he arrived at the hospital.

But that alone, despite the devastation of the crash, doesn’t necessarily prove impairment as a cause of Whitney’s death.

Alcohol, its effects on the body and its role in driving impairment have been thoroughly studied.

That’s not true for cannabis.

Further, THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana that makes people feel high, is much more complicated in how it interacts with the body, in part because it is fat soluble and remains detectable by blood tests for far longer.

None of this is soothing to Hixon, who simply wants the driver to be held accountable for her daughter’s death.

“We were told in the beginning that they were going to charge him with a DUI, with vehicular involuntary manslaughter and now he’s not,” Hixon said. “He’s getting a misdemeanor and that could be argued to a nonmoving violation.”

Landen M. Lewis, of Independence, has been charged with “operating a motor vehicle in a careless and imprudent manner, involving an accident.”

“It just makes me sick to my stomach,” Hixon said. “He could walk away from this.”

To Hixon, the lack of a felony charge says that her daughter wasn’t high profile enough to deserve accountability.

Two families are grieving.

Lewis’ mother, Holly Plummer, believes that the crash was an accident, partly due to the rainy conditions that day.

“It was an accident and he hit a pothole,” she said. “This is something that my son has to live with for the rest of his life.”

Advocates against impaired driving say the death of Kayla Whitney illustrates what they fear as Missouri potentially follows other states in legalizing recreational marijuana.

Her story, they say, speaks to scientific shortcomings in understanding, let alone measuring, how cannabis affects the body, especially when it comes to driving.

Missouri voters will decide if recreational marijuana becomes legal on the Nov. 8 ballot.

If Amendment 3 is approved, Missouri will become the 20th state to approve marijuana for personal use for people 21 years and older.

Anna Riley, a court monitoring project specialist with MADD Missouri, is working with Kayla Whitney’s family.

Mothers Against Drunk Driving is not taking a position on the passage of Amendment 3 and noted in a statement that alcohol remains the leading cause of driving accidents.

But MADD advocates point out that public sentiment and awareness regarding marijuana usage doesn’t include the same precautions as with drunk driving. For example, people are less likely to seek designated drivers when they’re high.

Riley pushes prosecutors to be as transparent as possible with victims’ families, especially concerning current law and proving cases beyond a reasonable doubt when marijuana is involved.

“We see them (victim’s families) getting a lot of false hope,” Riley said. “I’d rather them be transparent and say, ‘Hey, it’s the law that is holding us back from being able to really hold people accountable.’ “

The Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office declined to comment on the pending case.

But Michael Mansur, director of communication, acknowledged one of the issues for the criminal justice system.

“We currently have no test that can tell us when cannabis was consumed,” Mansur said. “So we cannot charge based on that drug.”

Pinpointing when cannabis was consumed and correlating a level detected in testing to any signs of impairment is currently being studied.

Researchers, working with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to study cannabis and driving, argued in a recent paper that “the legal cart is currently significantly ahead of the scientific horse.”

They are concerned that the push to legalize cannabis calls for a public policy discussion about impairment enforcement. But the science that should underpin such decisions isn’t complete.

THC levels are not the same as blood alcohol content. In Missouri, being over the 0.08 legal blood alcohol limit is well understood by the general public.

National studies for NHTSA are ongoing to develop standardized best practices for field sobriety tests that are specific to marijuana.

Pictures of the mangled wreckage that was the red Mustang involved in Whitney’s death attest to the impact of the crash near East 23rd Street and Wheeling Avenue.

“Blunt force trauma” was listed as Whitney’s cause of death, according to a Kansas City Police Department probable cause statement.

The document also notes “a high rate of speed” by the driver, allegedly to beat a red light, and fishtailing, according to witnesses, before speeding off again. Rain and the wet roadway were also noted by police.

“It’s somebody’s fault,” Hixon said of her daughter’s death. “Her life mattered.”

Seeking ‘The Number’

“Everybody wants a number.”

It’s a mantra of sorts among local law enforcement officials focused on taking cannabis-impaired drivers off the road before they cause accidents.

Law enforcement officials and researchers acknowledge that juries and legislators will likely push for a clear-cut limit to THC levels in blood draws. Ideally, “the number” for THC would be something comparable to the 0.08 blood alcohol content that deems a person legally intoxicated by alcohol.

But many experts contend that’s not a good idea.

“We just don’t have enough research right now to say X amount of THC in your blood equals impairment,” said Ryan Hutton, a trainer with Extract-ED Training. “There isn’t currently a number that should be representing impairment itself.”

Rather, he said, other methods of determining impairment should be the focus.

Hutton trains law enforcement nationally through Extract-ED Training, which is based in Jefferson City, Missouri.

“A lot of officers don’t have a ton of training on the drugs side of it,” Hutton said. “They may not have as much confidence as they do in detecting impairment by alcohol.”

It’s problematic and could lead to officers assuming that someone admitting to smoking marijuana, which drivers often do, equals impairment.

A “green lab” will be part of the training that officers from Kansas, Missouri, Florida and Minnesota will undergo later this month at an Extract-ED Training session in St. Joseph.

During the training, subjects ingest marijuana in various doses and then go through a series of tests, helping officers to learn how to detect impairment by various methods.

Similar testing, but under more rigorous standards, is being used for the research being conducted by Godfrey D. Pearlson, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Yale University School of Medicine.

Pearlson is also director of Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut, where much of the testing is occurring.

“We get volunteers stoned with different strengths of cannabis and have them drive virtual inside an MRI scanner and look at what happens,” Pearlson said.

The difficulty is in finding the “behavioral fingerprints” of cannabis, he said.

“We’re just not there yet,” Pearlson said.

In the popular imagination, some people believe that they can drive under the influence of cannabis without impairment, or that they drive better under the influence. Neither is true.

“Everyone has a strong opinion about this and most of those opinions aren’t backed up by facts,” said Pearlson, who also authored the book, “Weed Science.”

“Everyone has a strong opinion about this and most of those opinions aren’t backed up by facts.”

Godfrey D. Pearlson, author of “Weed Science”

People often believe that they drive safer because their sense of time is distorted – it often slows.

It’s the same reason that jazz musicians say that using marijuana slows them, allowing them to “play between notes, helping with improvisation,” Pearlson said.

But that’s not akin to being safer, or unimpaired as a driver.

Pearlson is part of a team of researchers working to measure all types of variables. Those include whether or not an individual is a heavy or infrequent user of pot, if they consume edibles as opposed to smoking, and how long people remain impaired, as compared to when they believe they are safe to drive.

It is known that THC impairs cognitive and psychomotor skills that are used in driving.

Pearlson noted, however, that drinking alcohol and then driving is far riskier than smoking a joint and driving.

According to a September 2021 article co-authored by Pearlson and archived by the National Library of Medicine, “These topics are more complex to address than commonly assumed, and raise additional questions – not all of which have straightforward answers.”

“Aside from alcohol, cannabis is the primary drug detected in the U.S. drugged driving cases and fatal motor vehicle crashes. But as we explore later, this statistic may be misleading due to the very marked persistence of THC in the body after consumption that is not necessarily reflective of impairment.”

The researchers hope to help inform field sobriety tests for law enforcement. They’re also studying what happens when cannabis is taken in combination with other drugs, which is increasingly common, but far less studied.

A combination was involved when Kizzy Dickerson’s daughter was killed.

Dickerson recently drove from her home in St. Louis to attend a MADD event at Berkley Riverfront Park.

Gaining any help with her grief, and her frustration with the processes of the courts, has been difficult, Dickerson said.

She carried with her a poster of her 20-year-old daughter, Ty’ana Bryant.

Firefighters had to use the Jaws of Life to pry her daughter and her friend from the car after it crashed into a tree in the Detroit area in 2018. Both young women died. The then 20-year-old driver ran from the scene, but was later arrested.

Dickerson said that the preliminary breath test of 0.185 for his blood alcohol content helped keep his bond high and, eventually, contributed to his conviction. The family didn’t have to rely on proving that he was also impaired by marijuana, although he admitted it to police.

Armond Humes was convicted on two counts of operating while intoxicated causing death and two counts of failure to stop at the scene of the accident when at fault resulting in death. He is now serving a sentence totaling 17 years.

“This is the least that I can do for my baby,” Dickerson said of her participation in the MADD fundraiser, a walk.

Her daughter was in college, studying to be a veterinarian.

Dickerson still receives restitution from Humes for the cost of her daughter’s medical bills and funeral expenses.

What’s needed is far more public education, not to scare people about the effects of marijuana on driving, but to inform them as the science improves, Pearlson said.

“There will be more stoned drivers and accidents,” Pearlson said. “The question is how do you limit the damage?”

Mary Sanchez is senior reporter for Kansas City PBS. This story is part of ongoing midterm election coverage by members of the KC Media Collective.