curiousKC: Winning Access to Fairyland Park Popular Amusement Park Became Civil Rights Battleground

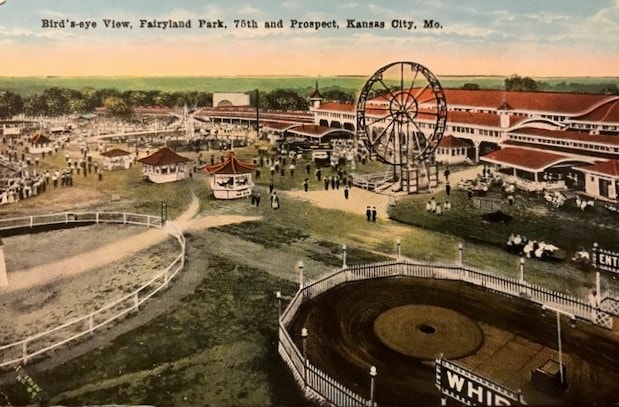

Postcard of Fairyland Park in Kansas City, undated. (Courtesy | Missouri Valley Room, Kansas City Public Library)

Postcard of Fairyland Park in Kansas City, undated. (Courtesy | Missouri Valley Room, Kansas City Public Library)

Published March 9th, 2020 at 6:00 AM

QUESTION: Did Fairyland Park, for decades a popular amusement park in rigidly segregated Kansas City, have a day, or days, set aside each year, around Labor Day, for African Americans to patronize it?

ANSWER: Yes – although the practice, which may have begun in 1932, evolved over time. By the early 1960s park operators were admitting black patrons as part of group events, especially school picnics – but not as individuals.

The public access policy at Fairyland Park, while hardly unique in a starkly segregated city, became a target of civil rights demonstrations the early 1960s.

The debate was ultimately resolved in 1964 when Kansas City voters approved a public accommodations ordinance mandating that taverns, swimming pools and other public facilities such as Fairyland become open to all.

Nearly 60 years later, Maria Brancato Accurso and her husband Vincent Accurso – daughter and son-in-law of the late Mario Brancato, who operated the amusement park for decades – do not recall one day being set aside for African Americans at the end of the summer season.

“There was not a specific day. It was never a hard-and-fast rule about the last day of the season,” said Vince Accurso.

More likely, added Maria Brancato Accurso, the idea evolved out of the popular practice of school picnics being scheduled every year.

“And if their picnic day was on a particular day, everybody with that group would come on that day,” Maria said.

While Kansas City’s public schools had been desegregated after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, they quickly had re-segregated as racially influenced housing policies steered black and white residents to different districts of the city.

Both Accursos say the park’s pre-1964 policies were not unique in Kansas City.

“To say that Fairyland Park was different from the rest of Kansas City would be wrong,” Vince Accurso said.

Segregation in 20th century Kansas City was documented as early as 1907, when black newspapers began to report that real estate agents were “increasingly reluctant” to sell or rent to black people in more desirable neighborhoods.

Notably, real estate developer J.C. Nichols deployed restrictive covenants that kept black buyers out of his developments, such as Armour Hills. The practice also was used by other developers.

By World War II the city’s African American population had been squeezed into an area largely north of 27th Street and east of Troost Avenue.

The war prompted early instances of civil rights activism in Kansas City.

When word spread that North American Aviation, then preparing to operate a bomber manufacturing plant in the Fairfax district of Kansas City, Kansas, would only hire African Americans to fill custodial roles, thousands filled the city’s Memorial Hall to hear several speakers denounce the policy.

That response, in context of the pending proposal of labor leader A. Philip Randolph that a summer March on Washington could showcase the issue, helped prompt President Franklin Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, prohibiting racial discrimination in the nation’s defense industries.

Still, much of Kansas City would remain segregated – including its amusement parks.

‘Clouds of Inferiority’

Kansas City residents long have patronized amusement parks.

Fairmount Park, which once boasted the largest roller coaster west of Chicago, operated in and near what is now Sugar Creek from the late 1890s to the early 1930s.

The “Electric Fountain” at Electric Park – which inspired a young Walt Disney – was among many attractions that attracted patrons from 1907 through 1925 to its location east of the Country Club Plaza.

There also had been a park built especially for black patrons – Lincoln Electric Park.

According to research recently submitted to the Black Archives of Mid-America, the park, which featured a swimming pool and several carnival rides, stood at 20th Street and Woodland Avenue, east of the 18th and Vine District.

Lincoln Electric Park operated from 1915 through 1917. Exactly when it shut down remains unclear.

Perhaps its brief success was one reason why, by 1932, operators of Fairyland decided to set aside several days at the end of the summer season for African American families.

This was, according to The Plaindealer, an African American newspaper in Kansas City, Kansas, “the first time” the amusement park would be open to African Americans “for six days.”

It’s unclear whether it represented the first time Fairyland set aside six days to serve this market, or it was the first time Fairyland management opened to African Americans.

Still, Fairyland took out an advertisement in the Sept. 2, 1932 issue of The Call, a Kansas City black newspaper.

The park announced a six-day schedule of events, some of them hosted by groups such as the Musicians Protective Union Local 627 and the Jackson County Colored Women’s Democratic Club.

Fairyland wasn’t the only park competing for this business.

The same issue of The Call included notice that Winnwood Park, which then operated between North Kansas City and Liberty, would be hosting the annual celebration of the Wayne Miner Post of the American Legion.

Formed in 1919, the post was named in honor of an African American soldier killed in action on Nov. 11, 1918, the last day of World War I.

By the early 1960s, Fairyland policy had evolved to where African Americans were admitted either as part of a group, or by prior arrangement.

Meanwhile, civil right activism was growing in Kansas City and across the country.

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at Kansas City’s St. Stephen Baptist Church in 1957, not long after the successful completion of the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott he had helped organize.

The following year Kansas City civil rights organizers picketed five downtown department stores, protesting the stores’ policy of not admitting African American patrons to its dining rooms.

By early 1959 the merchants allowed black patrons access to the restaurants.

In February 1960, four black students in Greensboro, North Carolina, sought to receive service at a local segregated lunch counter and helped launch a wave of protests against segregated facilities in several states across the South.

That same summer, members of the Kansas City branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sat down or lined up in several Kansas City area cafeterias and restaurants that did not serve African Americans. Some facilities, like the downtown Forum Cafeteria, soon agreed to allow equal access.

Then – in three separate events from 1961 through 1963 – protests focused on Fairyland amusement park and its popular spring school picnics.

In 1961 members of the local NAACP youth council began picketing the Kansas City Board of Education building. At an April meeting NAACP Kansas City chapter head Lee Vertis Swinton told board members they should end PTA picnics at Fairyland. While school officials were passing out picnic tickets to all students – black or white – black patrons were not allowed into the park after the picnic season, he said.

One school board member was more dismayed at the pickets outside the Board of Education.

“You should be picketing Fairyland,” he said

The next month police arrested 35 black protestors at Fairyland after their cars had blocked the park’s gates.

In 1962 police arrested about 25 NAACP youth council members who had stood at the park entrance for three hours while being refused admittance. Both times Fairyland’s manager repeated the facility’s policy — the park would admit African Americans only as part of groups, or for school picnics.

Some residents supported Fairyland’s policy. In 1962 members of a south Kansas City homes association told City Council members that they should not support integration at Fairyland, saying it was unfair to single out the facility for what they called “spot-zoning.”

But, for many, the segregation of amusement parks hurt in a unique way.

King, in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” published in 1963, explained the pain when “you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she cannot go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky…”

In August 1963, police arrested 16 members of the Kansas City chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) for entering Fairyland.

“For the record,” Police Chief (and future FBI director) Clarence Kelley said, “the demonstration tied up 12 patrolmen who could have been preventing crime while on patrol… I do not see what CORE can accomplish through this.”

About one month later, the Kansas City City Council adopted a broadened version of its 1960 public accommodations ordinance, this time including amusement parks, taverns, swimming pools and commercial golf courses, as well as business, technical and vocational schools.

Opponents responded by gathering a sufficient number of petition signatures to put the ordinance to a referendum vote.

In April 1964, Kansas City voters narrowly upheld the ordinance, approving it by 1,743 votes out of 89,209 votes cast.

‘Don’t Get Mad’

Fairyland continued to operate for more than a decade.

Worlds of Fun, which opened in 1973, presented new competition. Then a 1977 wind storm caused considerable damage to the park.

“The Ferris wheel had been toppled, bent completely over,” said Maria Brancato Accurso.

Park officials chose not to reopen the following spring.

While the site long stood largely unused, today the location has been transformed.

Some of the old Fairyland property is occupied by Alphapointe, a rehabilitation and advocacy organization for the blind and visually impaired, which opened a new facility in 2002.

Some of the old Fairyland property also is occupied by Paige Pointe, a townhome complex built by the Kansas City Neighborhood Alliance.

In 2002 alliances officials organized a bus ride to the new complex. Among the riders was the late Dorothy Stroud, an alliance board member and among those who had participated in the Fairyland protests of the 1960s.

The new uses of the old amusement park property represented appropriate reasons to revisit the site, she said.

“It feels real good,” Stroud said that morning. “I used to say, ‘Don’t get mad anybody, because one of these days, we will get there.’

“This is one of those days.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City-based writer.