Making Connections for the Future of Farming Farmer Networks Prove to Be Increasingly Important for the Passage of Land and Knowledge

Published October 12th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

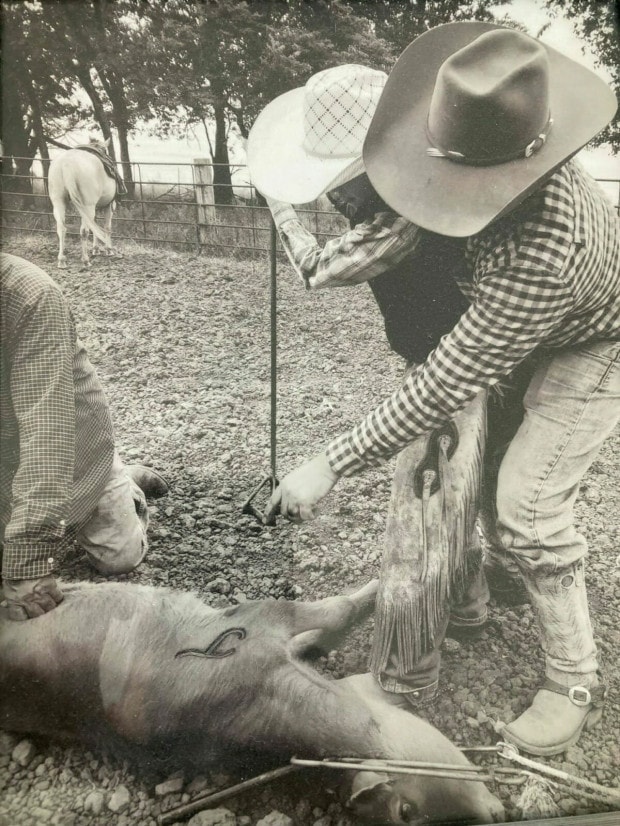

Above image credit: Farmers are more likely to implement a new practice if they can talk to a peer who has experience with it. (Contributed | Kansas Soil Alliance)Eddie Jaeger didn’t grow up on a ranch. But his first agriculture class in school inspired him to become a cowboy.

“I found that being a cowboy has nothing to do with rodeo, it’s about taking care of cows,” Jaeger said.

After college, he started working at feedlots, which drew him from his home in Illinois to Kansas.

“I got to be on a horse all day and take care of cows, and got paid for it,” Jaeger said.

As he started his own family, he saved up to start a small “grow yard” that nurtures high-risk calves before they head to a feedlot in north-central Kansas.

“My boy, he’s my right-hand man,” Jaeger said proudly. “Everything I do he’s right there.”

Jaeger’s son is only 14, but out among the cattle he’s an equal to Jaeger.

“I’m really hoping to build something up that I can give him when I’m gone, so that when he’s 30 years old he doesn’t have to fight for everything that he has,” Jaeger said.

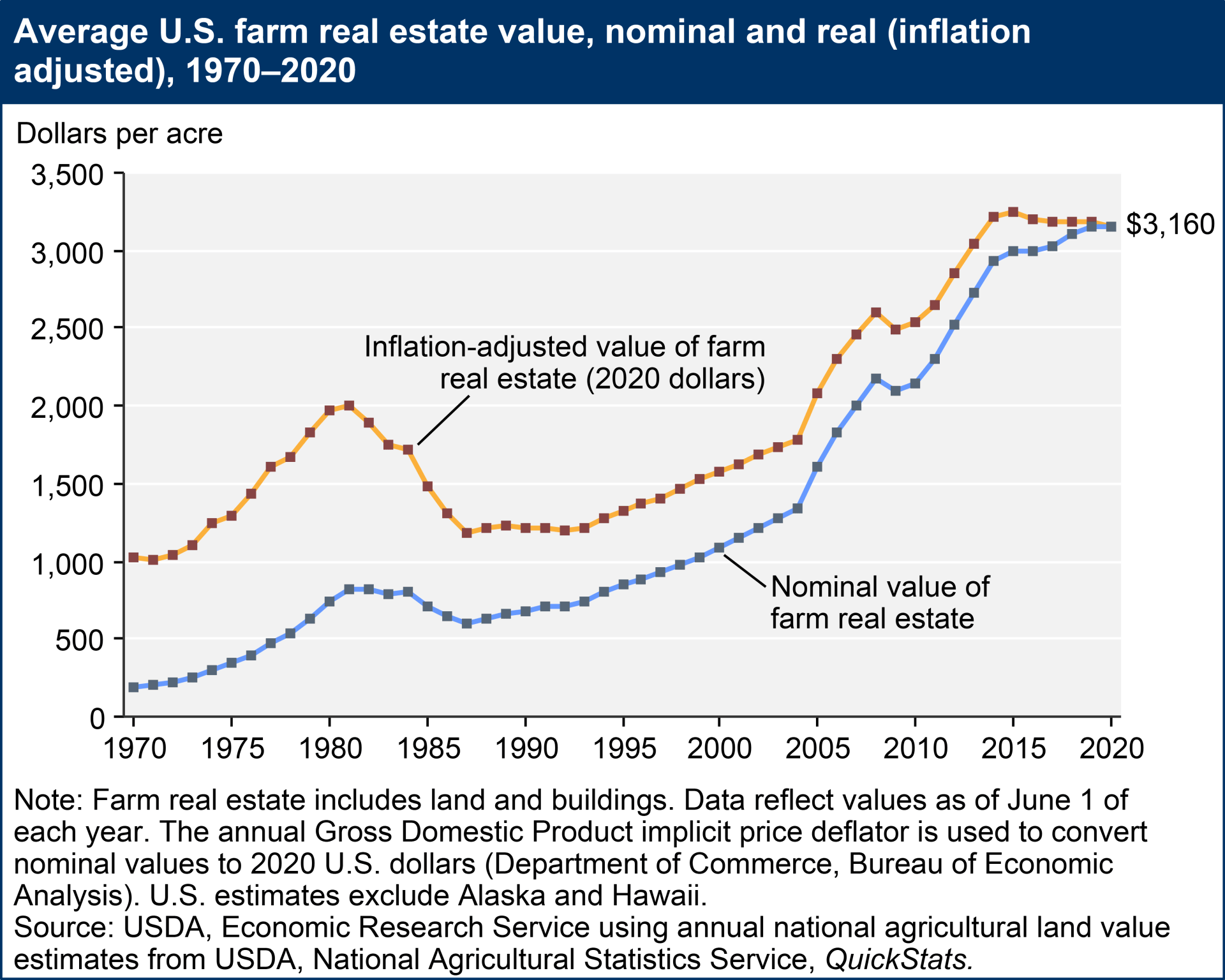

Buying farmland or pastureland today and starting a farm is significantly more expensive than it was for past generations.

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data, one-third of U.S. farmers are over the age of 65. About a quarter of U.S. farmers have farmed for 10 years or less.

As the younger generation of farmers looks to enter the business, it is vital they be connected to one another, and to their predecessors, to pass along knowledge and support.

Linking Up

Right now, Jaeger only has 22 acres and about 120 head of cattle. He still has a job in town to pay the bills.

That’s what led him to apply as a land seeker in the Land Link program through the Office of Farm and Ranch Transition at Kansas State University.

The program matches young farmers and ranchers with older landowners who are looking for a successor.

Jaeger has yet to be matched with a landowner, but his dream scenario is to have 500-600 acres of pasture that he can graze and pass on to his son.

“That would be more than I could ask for,” said Jaeger, who spent summers in his youth at his grandfather’s farm in Illinois. “What I have is not enough to pass on to him.”

Jaeger was drawn to the Land Link program because it gives small operators like him a chance to be seen by an older producer, who might otherwise sell that land to a bigger, already established operation.

“I know it’s going work for some people — I hope I’m one of them,” Jaeger said.

The K-State office started accepting applications for the program in July 2022 and so far has 18 landowner applications and 90 land seeker applications. Ashlee Westerhold, the director of the Office of Farm and Ranch Transition, said the process has been slow.

“We do not take this process lightly,” Westerhold said. “We want to make sure that the landowner feels comfortable moving forward.”

Some land seekers, like Jaeger, are already settled in one area and, while they’re interested in being matched, don’t want to move across the state for the pairing. Westerhold said many of the applicants are interested in cow-calf operations, while most of the landowners farm row crops.

Landowners who apply want to give a young family the opportunity to take care of their land, rather than sell it to a larger, established producer. Other farmers have their land in a trust for their children (who don’t come back to the farm), and they want to have a reliable, full-time farm manager to keep the land profitable.

“(Landowners) want to have farmers and ranchers in their town, and they really understand that it is truly almost impossible, unless you have inherited a large sum of money, to be able to get into farming. They want to provide that opportunity for someone to be able to do that,” Westerhold said.

Westerhold stays in contact with the landowners and land seekers long after they are linked, to make sure agreements are kept and a succession timeline is followed. This could mean the parties work together for several years before a land transfer happens.

“It’s not a you-get-matched-and-you’re-out-of-my-realm (process),” Westerhold said. “I will follow you through the end of my tenure… Transition planning is not a one-day event.”

So far, the program has only connected a couple of producers, who are still in the early stages of the process.

In Missouri, FCS Financial, a farm credit cooperative, started a similar program several years ago and ran into a comparable situation — more land seekers than landowners, and with misaligned interests.

“When it was down on paper, the program in theory was right, and for whatever reason, we just never could gain the traction,” said Kate Lambert, the co-op’s vice president of marketing.

Instead, FCS Financial has found success supporting succession planning and young farmers in a different program.

More Than Just the Land

In addition to reduced credit standards for younger producers, FCS Financial offers classes and programs to teach the business of farming and to have more of a “CEO mindset,” which Lambert said is necessary with the size of most ag operations today.

“One of the best things we can do is equip these young people to have access to this information and start developing some of this business acumen and financial skill sets,” Lambert said.

That way, when opportunities arise to buy land or to transition land from one generation to another, young producers are equipped for those conversations.

K-State offers similar education to families and young producers.

The Connect program also builds networks between young producers so they can support one another through the stressful and difficult industry that is farming.

“Farming is hard. It’s hard for the producers and their spouses and their families,” Lambert said. “So, putting those people together in a room and helping them to establish that network is super critical.”

Since the formation of the Connect program in 2015, Lambert said, more than 560 young producers have taken part. Those who qualify are 35 years old or younger or have less than 10 years of farming experience.

Farmer-to-farmer connections are important at all stages, but especially for young producers. Folks who are just starting their farms and are new to the industry will need a network of producers to get connected to vital resources and learn some of the skills.

Other young producers are returning to the farm and learning how to be in business with family members.

“For every farm family that I know … it is absolutely their goal that they preserve and maintain and improve that farm for people to pass it down in better condition than when they received it.”

-Kate Lambert, FCS Financial

“When you’re eating Thanksgiving dinner with your business partners, that’s just a very different dynamic than what many of us experience in the professional world,” Lambert said. “Being able to connect with other people who are having those same conversations with mom and dad and grandma and grandpa and those same frustrations, is just really important.”

FCS Financial also hosts an annual Connect Ag seminar to bring producers (co-op members or not) together to talk about succession planning and facilitating the right conversations. This year’s seminar will take place Dec. 6 in Maryville, Missouri.

“We can really get things ironed out when it comes to actually transitioning the real estate and the equipment,” Lambert said. “What we’re not so great about in the industry is passing on the business and the skillsets and the knowledge.”

Farm succession is not only land and documents and money, but it’s also equipping a new generation of producers to steward that farm.

“For every farm family that I know … it is absolutely their goal that they preserve and maintain and improve that farm for people to pass it down in better condition than when they received it,” Lambert said.

Farmer to Farmer

Peer networks are beneficial to producers at all stages. Farmers, as with folks in any industry, relate to more and trust other farmers when it comes to sharing knowledge.

This summer, Kansas Sen. Jerry Moran and New Mexico Sen. Ben Lujan introduced the Farmer to Farmer Education Act to expand farmer-led technical assistance in the Food Security Act.

A press release from American Farmland Trust about the bill notes that farmers are more likely to adopt conservation practices like cover crops or rotational grazing when they hear about it, and see the results, from a neighboring producer versus traditional USDA or extension outreach.

Facilitated farmer-to-farmer conversations can also empower first generation and minority farmers, who often don’t have the legacy knowledge or networks that others have.

Locally, the Kansas Soil Health Alliance has partnered with the Kansas Association of Conservation Districts to build these farmer networks and promote the principles of soil health.

Jennifer Simmelink, a coordinator with the Kansas Soil Health Alliance, said her involvement is intentionally minimal. Each month she reaches out to the conservation district managers to see if they’ve had any meetings. Sometimes she will suggest a topic to discuss, but really the meetings are organic and up to the producers attending.

“This isn’t meant to create a burden on anyone,” Simmelink said. “We recommended that the discussions do not take place in the USDA service centers, where it feels like a formal meeting or a recruitment tool… The intent is: let’s go out in public, let’s have these easy, relaxed discussions.”

Folks meet in coffee shops, bars or even in a pumpkin patch. It’s about creating a place where farmers can talk shop with one another and hear firsthand what worked and what didn’t.

“For them to get together and for someone to try (a new soil practice) and say, ‘Yeah, this worked’ or ‘This didn’t,’” Simmelink said. “I just think that’s where it’s needed because … farmers inherently will trust each other.”

Simmelink encourages farmers to get in touch with their conservation district managers and to check the alliance events page to get connected.

Jaeger speaks with admiration at his son’s commitment and knowledge of the cattle they raise.

“Hell, I can talk to him like he’s 30 years old,” he said.

Jaeger didn’t get to work with cattle until he was an adult. His son, on the other hand, has grown up around the cows.

“I feel like he’s cheating,” Jaeger joked. “I wish that I had this when I was growing up, and it’s overwhelming that I can give this lifestyle to my son.”

Jaeger has passed on his knowledge and skills. Now he just needs some land of his own to set up the next generation of Jaeger stewardship.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.