The Resonant Legacy of Pipe Organs in Lawrence, Kansas The College Town is Prominent on the Map of the Organ World

Published April 5th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: Most organs require regular tuning and occasional rebuilds. Plaques between the rows of keys display information about the organ's construction. (Cami Koons | Flatland)LAWRENCE, Kansas — As a teenager, Dan Abrahamson would turn pages for his sister as she played the organ.

From where he stood, to the right of the bench, he could feel the air expelled from one of the pipes each time its note was played — like a living, breathing thing.

“The organ was alive so to speak,” Abrahamson said. “So that’s when I decided I wanted to go to school and learn to play the organ correctly.”

Like many who get involved with the instrument, it became an enduring love.

He went on to play the organ for most of his life, dedicate a career to building the instrument and renovate the organ at the First United Methodist Church in downtown Lawrence to be the largest pipe organ in Kansas.

But that’s just one organ claim-to-fame in the college town.

It’s also home to Reuter Organ Co., which hand-crafted more than 2,000 organs across the country during its 105 years in service. And the University of Kansas houses one of the largest organ departments in the country, which is regularly visited by world renowned organists.

Craftsmanship

Abrahamson moved to Lawrence in 1961 to work at the Reuter Organ Co.

Reuter (pronounced: roy-ter) was already established in Lawrence at the time. Formed in 1917 in Trenton, Illinois, Reuter relocated to Kansas in 1919 to capitalize on easy access to rail transport, and a less saturated market.

From its location downtown, the company produced organs for churches and concert halls nationwide, including the then 44-rank organ at the First United Methodist church in Lawrence.

In 1963, when Abrahamson was asked to fill in as an organist at the church, the instrument built in 1938 was in disrepair.

“You’d turn the organ on, and it would sound like Niagara Falls … (and) it was so out of tune it sounded like Halloween,” Abrahamson said with a laugh.

He convinced the church to invest in repairs, and he struck up a deal with the foreman at Reuter to sell him discarded pieces (which were otherwise melted down) at a steal of $25 a rank.

“Whenever I lucked into a set of pipes, I’d put them in,” Abrahamson said.

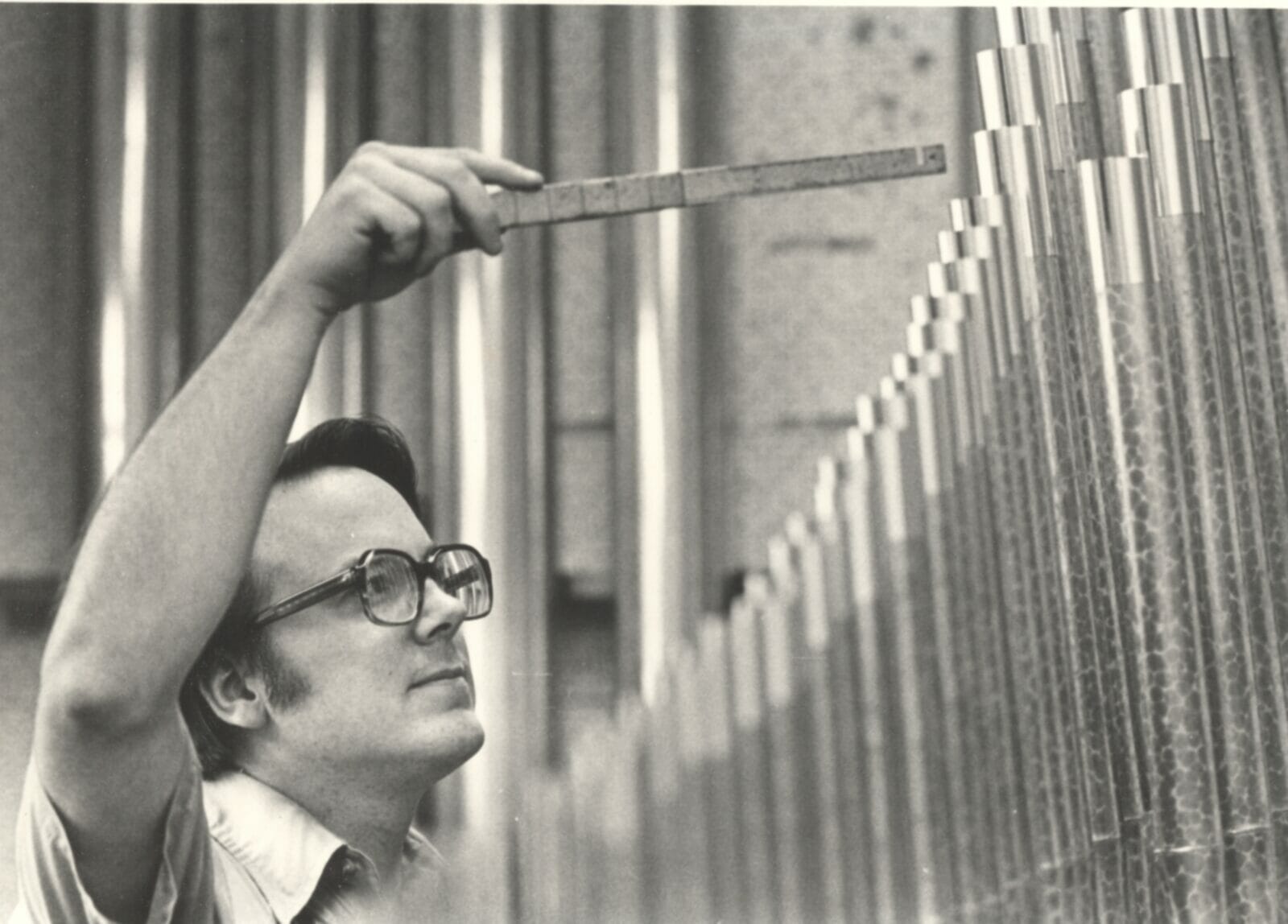

He continued expanding the church’s organ for decades, stopping as he retired from Reuter in 2001. Today the organ has 123 ranks, totaling over 7,000 pipes, more than the huge organ at the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts.

Abrahamson enjoyed tinkering with and improving the sound of the organ, as did most of the skilled employees at Reuter.

Max Mayse also worked at Reuter, and in retirement has become a Reuter historian with an office full of archive materials and a book in progress.

Like Abrahamson, he became infatuated with the instrument at a young age.

“It’s one of those things — it’s just so fascinating that once you get bitten by the bug, you just stay with it,” Mayse said.

In the fashion of a true historian, Mayse veered off the Reuter history timeline while speaking with Flatland to share some of the interesting facts he’d learned over the years. He noted that the first Reuter Organ, housed at Trinity Episcopal Church in Mattoon, Illinois, was the second organ made by the company. The first was destroyed by a storm that hit the factory. Another Reuter organ in Oregon has a complete digital version, with an audio sample from each of its 3,094 pipes.

When it started in 1917, Reuter employed just six people. But the company grew to employ 125 and had order backlogs approaching two years during its peak in the 1960s.

The company’s promotional film, “Making A Sound Decision,” from the 1960s detailed the process of building a Reuter Organ. From selecting raw materials, to shaping the pipes and hand “nicking” them for a uniform sound, employees were highly skilled craftspeople.

Musical Manufacturing

Reuter organs were fully assembled and tested in the shop, then taken apart and shipped to the installation site. Employees would travel to help assemble the instrument, and voicers, like Mayse and Abrahamson, would ensure the instrument was tuned and tweaked to be just right for the space.

“Reuter built everything,” Mayse said. “All of the pieces, all of the pipes. The keyboards were built by one guy for 50 years — his name was Gilbert.”

While there were many organ builders across the country, Mayse said maybe half a dozen of them did it all as Reuter did. Other builders sourced their materials and components from other companies.

“It’s a fascinating instrument, because they’re worse than fingerprints — there’s absolutely no two alike anywhere in the world,” Mayse said.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, Mayse said many organ companies went out of business. Reuter itself struggled as production and orders dropped significantly, but it managed to rebound and keep up its quality.

The organ can be understood by thinking of a keyboard or a synthesizer. The “principal” sound on a keyboard would be a piano. On an organ it’s the big pipe sound a-la “Here Comes the Bride.” But, like a keyboard, with the push of a button, or the pull of a stop, the instrument can sound like a set of strings, a flute, a trumpet or a bell.

When Reuter designed church organs, which accounted for about 90% of sales, it kept three principles in mind.

First, it had to be able to play hymns and accompany the congregation as it sang. Second, it had to be able to accompany soloists and choirs.

And the third priority was to play literature, the classical organ music. Certain organs are best suited for certain literature (German, French, English etc.) but Mayse said Reuter built in an “eclectic style.”

“We tried to design our organs to not perfectly play everything, but adequately,” Mayse said. “So you can play French literature on a Reuter, and you can also play German literature on a Reuter.”

Pop Culture Moment

In 2001, the company moved to a new location west of Lawrence, where it continued for another 20 years. Just last year, J.R. Neutel, the current owner and president of Reuter announced the company would scale back its operations and focus on servicing existing Reuter organs through their remaining warranties.

“Very, very few companies make it past the 100-year mark, Reuter made 105,” Mayse said.

The Greater Kansas City Area chapter of the American Guild of Organists is hosting an event later this month honoring Reuter’s heritage.

Crimson and Bales

Up the hill, the organ department at the University of Kansas boasts an even longer history.

It started in 1867, just one year after the university opened its doors, and persists as a leading program with a capacity of 20 students in the major, masters and doctoral programs.

“We have very, very gifted students,” James Higdon, director of the Division of Organ and Church Music at the university, said with pride. “We always have very gifted students.”

When Higdon arrived at the University of Kansas in 1980 to teach, he believed the department needed a better recital hall. Backed by the dean, he looked for funding and met Dane and Polly Bales.

Prior to the opening of Allen Fieldhouse, the Jayhawk basketball team practiced in Hoch Auditorium — which was also home to the school’s organ. Polly Bales remembered practicing organ at the university, with a cage around the organ console to protect musicians from any stray balls during basketball practice.

When Higdon approached the Bales about building an organ concert hall, Polly Bales was enthused.

The Dane and Polly Bales Organ Recital Hall opened in 1996 as one of the finest organ facilities in the country and has since housed countless recitals and talented organists. The hall is a regular recital site for Olivier Latry, an organist at Notre Dame de Paris and professor of organ at the Conservatoire de Paris, who spends a week at the university each semester.

“It’s really perfect for organ research study,” Higdon said. “It’s just ideal, not because I say so, but because others do.”

Higdon describes the 65-rank Hellmuth Wolff, Opus 40 as an “eclectic organ with a French flavor.” The Bales Recital Hall was built entirely to specification with the organ and features 2-foot-thick concrete walls and a controlled temperature to keep the materials from degrading.

Including the crème-de-la-crème at Bales, students in the organ department have eight pipe organs across campus to practice on, a big advantage for the program. Students also have no trouble finding part-time work at Lawrence, Topeka and Kansas City churches.

Access to rehearsal space is a key element for organ students. That and the Bales Recital Hall are what compelled Andrew Morris to pursue his undergraduate, masters and a doctorate in organ performance at the university.

“It has great facilities which are really not rivaled elsewhere in the country,” Morris said. “If you play the organ, it’s like a paradise there.”

Now, at the Conservatoire de Paris, Morris studies in the same place as famous composers with students from all over the world, yet many there are familiar with KU’s program and the Bales Recital Hall.

Future Ranks

The organ is a deeply complicated instrument. Not only is the music difficult to read and play, with three or more lines to read at a time, but an organist must also learn each organ, as they’re all different.

It’s not the instrument of choice for everyone. But Morris, who hopes to teach in the future, has no fear that students will always be drawn to the instrument.

“I don’t think that will ever really be a problem, because those that come to the organ, they’ve sought it out for some reason, and they’re really invested,” Morris said. “And the skill always seems to be getting higher and higher.”

Higdon echoed the sentiment, saying undergraduate students of late have entered the program already skilled on the organ, when prior classes did not.

It’s true that folks have been “bitten by the bug” for centuries (the organ dates back before 300 B.C.), but the culture around the instrument has changed.

There are more churches closing than opening, and many have turned from traditional services to modern services favoring drum sets and keyboards. Concert halls and university auditoriums are still built with organs, but the demand is nothing like it once was for the custom and pricy instruments.

In her years of study, Tandy Reussner, an organist in Lawrence with a doctorate from KU, learned to play traditional literature such as Bach and Mozart. She loved and appreciated the pieces, but never felt they were accessible to today’s culture.

“I just thought when I got out, I wanted the organ to be relevant to people,” Reussner said.

So, she mixes things up, by arranging modern, recognizable tunes to fit the organ, or creating shorter, more digestible versions of established organ pieces.

“I get a lot of flak for ‘cheapening’ it, but I really try very hard that whatever I play has to be top quality,” Reussner said.

Reussner has, for 26 years, hosted a yearly Christmas concert for the community and used it to raise money for local charities. But this year she decided to take it a step further, scheduling a series of four concerts, each with a different theme and benefiting a different local charity.

“It was to figure out how can I reach different types of populations who may not have ever wanted to step foot, one in a church (or) two in a concert hall to hear a pipe organ for an hour,” Reussner said.

The first installment of the concert series was around Halloween with macabre sounding Bach, and an opera piece transcribed to the organ and featuring an electric guitar.

The second installment featured Christmas tunes like “Sleigh Ride,” and accompanied pieces with the Lawrence Children’s Choir. To kick off March Madness, Reussner had a Kansas-themed concert with the Lawrence Bar Band and Kansas classics from the “Wizard of Oz” to “Home on the Range.”

Over the Rainbow

“It’s been relegated to not relevant. I don’t want to hear it, that’s for old people,” Reussner said of the instrument. “It is such an incredible masterpiece of engineering and art that I really want to make it accessible to other people and want them to hear what it can do.”

The concerts have been hosted at the First United Methodist Church, where Reussner is the organist. Between songs, she shared facts about the organ, its uses, or a video of the pipes and chests tucked behind walls so the packed sanctuary can learn a little more.

The last installment of the Pull Out All the Stops series is slated for July 2, and set to feature patriotic tunes. Proceeds will support Family Promise of Douglas County.

Reussner’s motivations are twofold — to get folks interested in the organ so it doesn’t die out, and to bring the community together around music.

“It’s not in our culture. So even though I can’t change the culture, I can do my little bit here, and hopefully we can get a little bit of enthusiasm for it,” Reussner said.

Disclosure: Cami Koons is a member of the First United Methodist Church in Lawrence.

This post has been updated from an earlier version to correct the spelling of a name.

Cami Koons covers rural affairs for Kansas City PBS in cooperation with Report for America. The work of our Report for America corps members is made possible, in part, through the generous support of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

My father worked for The Estey Organ Co., in Brattleboro, Vt. from the age of 13 in 1912, and stayed with them until they went out of business in 1958. I have his voicing tools, and other tools. Would like to find a new “home” for them. Please, contact me

My father was employed by The Estey Organ Co., from the age of 13 in 1912 until they went out of business in 1958. I have his voicing tools, and other tools of his. I would like to find a “new home: for them. Many he made. Please, contact me at my email address.

Wonderful article. But if the organ has become irrelevant it is because the quality of music popular to the culture has deteriorated. What they purport to be culturally relevant music now is largely frivolous in lyrics, violent, and ugly. Modern music is not worthy of the music of the organ, and this is a good measure of a dying society when the organ disappears. But…the organ will be back–when civilization is.