National WWI Museum and Memorial Curator’s Career in 10 Objects After close to 33 years as curator at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, some artifacts remain proven conversation pieces for Doran Cart.

Published December 22nd, 2022 at 6:00 AM

There are almost 500,000 objects held by the National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Retiring Senior Curator Doran Cart recently agreed to talk about 10 of them he found especially meaningful.

He started not with 10 but 9,000 – the number of silk poppy blossoms visible from the glass bridge that visitors cross to approach the museum’s main gallery from its lobby.

“The poppy field is the only exhibit in the museum that doesn’t have a label on it,” Cart said. “That’s because we always want this exhibit not to be just read about, but explained by a person about what it symbolizes.

“Each of the 9,000 silk poppies represent 1,000 dead directly from the war. So 9 million dead are represented here, and we want visitors to have a direct connection to those people.”

Cart, whose last day will be Dec. 31, represents an institutional memory that may be unique among Kansas City area museum professionals

He can articulate several ways in which the museum and memorial has grown and evolved since his arrival in 1990. He can explain how specific objects were sought and obtained, and detail how they arrived from a private collector in Russia, a representative of a women’s college in Massachusetts, or a distant relative of former German Field Marshal Paul Von Hindenburg, who one day called Cart’s office phone number from his home in Colorado.

But he’s also eager to point out how it’s not just any apparent scarcity or novelty that explain an object’s display. Instead, the emphasis is more on how the artifact can help visitors bridge more than 100 years since the object’s manufacture or deployment, and bring the distant war close.

“Everything that I have put into the museum deals with the humanity of the people in the war,” Cart said.

“So if it is not directly connected — if not to an individual but to a people or a country — then it really doesn’t have a full story. Everything has to be connected in some fashion for me to get satisfaction out of it.”

Instruct or Inspire

When Cart arrived in 1990, he and an archivist supervised the artifacts and documents the facility held and collected.

Today, the museum has about 50 staff members.

When he arrived, visitors to the Liberty Memorial could enter either Exhibit Hall to the west of the memorial tower or Memory Hall to the east, the latter enshrining the names of the 441 Kansas City residents lost during the war.

The two halls totaled about 5,000 square feet.

In 2004, when Congress designated the facility as the nation’s official World War I museum, construction began on a new 80,000-square-foot museum and research center underneath the Liberty Memorial.

Then there is the vast number of objects the museum holds, about one-third of which have come into the collection during Cart’s tenure.

Because of the reputation the museum has developed, possible donations keep being offered on an almost daily basis, Cart said

But the museum typically accepts only about 20% of what is offered.

“Since the museum has collected for more than 100 years, after a while you have all the bases covered,” he said.

About 99% of the objects the museum acquires are through donations, Cart said. The rest represent purchases made of materials to enhance the museum’s collection, Cart said, in areas where donations are not available.

“Of course we have to fundraise for that,” he said. “We have to ask for help from our donors and supporters.”

Cart’s collection of objects from around the world, assembled in a cumulative way over more than three decades, helped the museum emerge with clear credibility during the recent world-wide observance of the war’s 100th anniversary, Matthew Naylor, museum and memorial president and CEO, said recently.

“His unparalleled knowledge of WWI objects strengthened our work and drove us to new heights,” Naylor said.

Every object or collection of objects now on display, Cart added, is there to either instruct or inspire.

“So it is very hard for me to say I have favorites,” he said. “But I do have those I like to talk about.”

What follows are Cart’s descriptions of 10 of the museum’s most notable items:

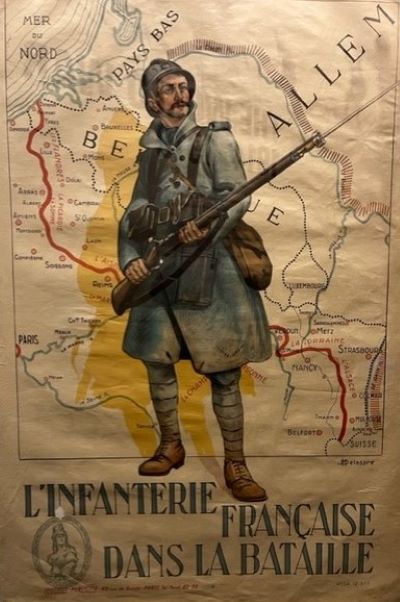

About 1,600 Posters

“Color lithography had been developed just before the war, and every country involved in the war produced posters representing what those countries were doing, if they were fundraising, recruiting or distributing propaganda.

“The museum probably has around 1,600 posters, and not all posters spread propaganda. Some were very truthful. This is a recruitment poster, seeking new members of the French infantry. You don’t see any representation of the enemy. It only showed the French soldier but also where the war was going on.

“English writer Martin Hardie stated in 1920 that the poster’s role during the war was to ‘waylay and hold the passersby and to impose their meaning upon them.’

“That’s what we want posters to do here at the museum.”

Paul von Hindenburg’s Field Jacket

“I was sitting at my desk and got a phone call from a fellow in Colorado.

“He said he was a distant relative of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the second most powerful man in Germany during World War I.

“He said he had one of his uniforms and asked if I would like it for the museum.

“I told him I could be in Colorado in about 15 minutes. He said ‘You don’t have to do that; I’ll bring it.’ And he and his family came to Kansas City and donated the uniform and the cap.

“Now, von Hindenburg probably had 30 or 40 uniforms, because he liked uniforms. But we do know that he actually wore this one, because when I was researching it I found a picture of him wearing it. And this is the one, because if you look at the collar, and you see how that collar is bent up there? It also is bent in the photograph.

“Plus, it has his tailor’s label, so it is the real deal.”

Russian Cossack Uniform

“Our exhibit of uniforms shows the global aspect of the world war, and one of the areas I have really concentrated on is collecting objects from the Russian part.

“Most museums, when addressing World War I, simply talk about the Western Front.

“But our focus is international, so we talk about Eastern Front.

“The Cossacks were mountain troops and were fairly independent. This uniform is from what was called the ‘Wild Division.’

“One challenge of Russian uniforms is that Russian soldiers were in the ‘World War’ for three years but then became part of their own war. There were four revolutions in 1918, and so to get objects still remaining from that time in Russia is pretty amazing, because that history was really pushed away when the other regimes came in and took over.

“So, to get a Cossack uniform is amazing, especially this one, which came in complete with its belt.

“This came from a private collector in Russia. Most of the Russian objects I have been able to acquire are part of the one percent of objects we have purchased.”

Imperial Russian Nurse’s Uniform

“When I started here, we had very few objects representing women’s roles in the war, because it had not been a collecting initiative before.

“This was a uniform worn by a Russian nurse. It is silk, with a cotton apron and head-scarf. The button right at the top was for the Russian Red Cross.

“The other interesting point are the chevrons on the sleeve, with the white, blue and red of the original Russian national flag, which is what they use today. If this nurse would have been caught with this on her uniform when the Bolsheviks took power, she would have been executed. She was with the ‘White’ Russian army.

“So, to have this uniform survive all that went on — and how it belonged to a woman who was active around the battlefields — and now to be here in the museum? That’s as good as it gets.

“It came from a private collector in Russia. What happened is — we think — is that people put these things in their trunks, kept them in their houses and didn’t bring them out again until recently. There aren’t any museums wanting this kind of stuff there, because they really go all the way back to the (early 19th century) Napoleonic Era, and then to the ‘Patriotic War,’ which was World War II.

“And so these uniforms were kind of ‘orphans’ and for us to get one of the ‘orphans’ here – you are not going to see this anyplace else.”

Signal Corps Women Telephone Operator’s Uniform

“During the war more than 300 American women went overseas to serve as telephone operators.

“They were members of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, working close to the front lines. Many of them had been recruited from telephone companies, and many also had been teachers who could speak French, with all of the communications necessary between the French and American forces.

“So they served in the Army, and they wore dark blue wool uniforms.

“The poignant thing about this uniform is that it was worn by a woman named Olive Shaw. Olive lived for a long time after the war and in 1977 she was among approximately 40 of these women telephone operators who were still alive. That year an attorney named Mark Hough had collected affidavits from these women because, even though they had been in the U.S. Army and had been under (Gen. John J.) Pershing’s command, they had never been awarded veterans benefits.

“And so Mark Hough gathered all of these affidavits, along with personal objects and documents from these women, and then went to Washington and argued before Congress that these women should be awarded veterans status. These women had not received anything for their service.

“He was successful, and one of the reasons he was successful was Olive Shaw. She testified before Congress, wearing this uniform.

“She said, ‘Of course I was in the Army. What are these buttons? These are U.S. Army buttons. I am wearing them.’

“She said, ‘If we weren’t in the Army, then no one was.’

“So Olive and the approximately 40 others still alive received veterans benefits from Congress. “Since only about 40 of the original 300 women were still alive, it was kind of a hollow victory, but it was still a victory. Mark Hough, who did all this work, donated all of his documents to the museum, along with Olive Shaw’s uniform.”

Harlem Rattlers Uniform

“During World War I African Americans serving in the U.S. Army served in segregated units, with white officers.

“The first African American regiment to go over to France was the 369th Infantry Regiment, from the 15th New York National Guard. They served under French command because the U.S. command structure didn’t trust African American soldiers to fight. They proved them wrong right off the bat.

“This is a uniform from that regiment, the Harlem Rattlers — that was the nickname they got. Because they were under French command, they wore a French helmet until the middle of 1918.

“It was a time of hate-filled segregation, but these men served admirably throughout. The most famous member of the 369th was Henry Johnson.”

‘America’s Entry Into the War and the 20th Century’

“I am extremely proud of the Kemper Horizon Theater film, which shows how America entered the war, but also gives the background,” Cart said.

“We worked on it with the movie production crew and the film is so purposeful, yet it doesn’t take any sides. It simply tells what was going on. It’s 14 minutes of really great information.

“We have never had a visitor who watched the movie and then said, ‘What did all that mean?’ They have always said, ‘I’m so glad you did this.’

“So, if I have to say one of the most interesting things in the museum that I have worked on, it’s this movie.

“You can also see the battlefield represented in the theater. … Everything in the museum has been important to me throughout my career here, and I am still learning about World War I and the people who were involved in it, as well as its lasting effect on the world. Just today I saw a picture of a trench in Ukraine, shown alongside a trench from World War I.

“It looked exactly the same. We still haven’t figured out how to get out of these wars.”

British de Havilland DH2 Reproduction Airplane

“My one real disappointment, in being here all these years, is that I was never able to acquire an original World War I airplane.

“The three airplanes here in the museum are great reproductions, but they are not original to the war. Most of the original airplanes did not survive.

“I don’t think it is a failing, because we tried. We tried for years to get one. And that search has not ended. I have connections and I talk to people all over the world, so I am going to keep that up even as curator emeritus.

“This airplane was considered a ‘pusher’ plane because the pilot sat just in front of the propeller. This type was mainly used in the desert, so it has the desert colors.

“This plane was placed here because – if we did ever find an original airplane – we could bring in the Belger Cartage heavy equipment to take the reproduction down and put the original airplane up.

“The other places in the museum where there are airplanes, they are above exhibits and you can’t reach them.

Doughboy’s Pack

“The American ‘Doughboys’ were called that because before the war the American infantry soldiers serving on the Mexican border would be covered by adobe brick dust. Then the cavalry would ride by and they would say, ‘Look at all the marching adobes.’

“That went from ‘adobes’ to ‘doughboys.’

“All this stuff would go into the ‘Doughboy’s’ pack. Everything from cracker boxes — and those still have original hardtack crackers in them, they’ve never been opened. Mess kits, emergency rations — that emergency ration there was a big, hard chocolate bar made in Kansas City — and an emergency medical kit, toilet paper, shaving powder and an extra shirt and undershirt, as well as an extra pair of underwear and wool socks.

“And then you have what they would have carried in their pockets. That was where they could have a personality, where they could have something that wasn’t ‘Army-ordered’ for them.

So dice, matches, or playing cards. And letters. And pieces of French cathedrals – they picked up glass from them. And coins. And the New Testament, and a Jewish prayer book.

“Any army we could have picked, we could have done the same thing with.”

Gen. Pershing’s Flag

“This is Gen. John J. Pershing’s headquarters flag. He was the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces and this flag flew over his headquarters in Chaumont, France.

“How we got the flag is a really important story.

“Pershing’s wife Frances — everybody called her ‘Frankie,’ — and her three daughters were killed in a fire at their house at the Presidio in San Francisco in 1915.

“They had just shellacked the floors and ashes fell out of one of the home’s stoves and the wooden house burned down. Their son Warren and the family nanny got out alive.

“Of course, Pershing had been devastated by this.

“Frankie had been a member of the Agora Society (a student group which discussed social welfare issues) at Wellesley College.

“So Pershing is in the middle of the world war, in France in 1918, and the Agora Society wrote him a letter, saying they were making him an honorary member.

“He was so touched by this that he had his aides take the flag down, pack it carefully and send it to the society at Wellesley as a small token of his appreciation.

“The flag was framed and hung in a hallway in the Wellesley College library for many years.

”Some years ago one of our trustees, who had gone to college at Wellesley and was visiting during an alumni event, saw this framed flag hanging in a dark hallway and asked a librarian about it.

“The librarian told our trustee the story, and also said the library was being renovated and that the flag was not expected to be exhibited in the new library.

“So our trustee asked whether she could speak to the curator and see if the flag could be transferred to the museum. And so Wellesley transferred the flag to us, as well as a copy of a letter that Pershing had included with the flag. We had a fine arts shipping company ship it to us, and I had it re-framed on acid-free backing board and put it on exhibit.

“I often think about the meaning of this flag, and I think it really is the meaning of all of the objects here in the museum. Because all of the individual objects represent someone who either made it, or wore it, or preserved it, or died with it.

“This flag encapsulates all of those emotions, all of those purposes. And here it is. This flag flew in France over Pershing’s headquarters; now it flies at the National WWI Museum and Memorial.

“It can’t get any better than that.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author. He is serving as president of the Jackson County Historical Society.