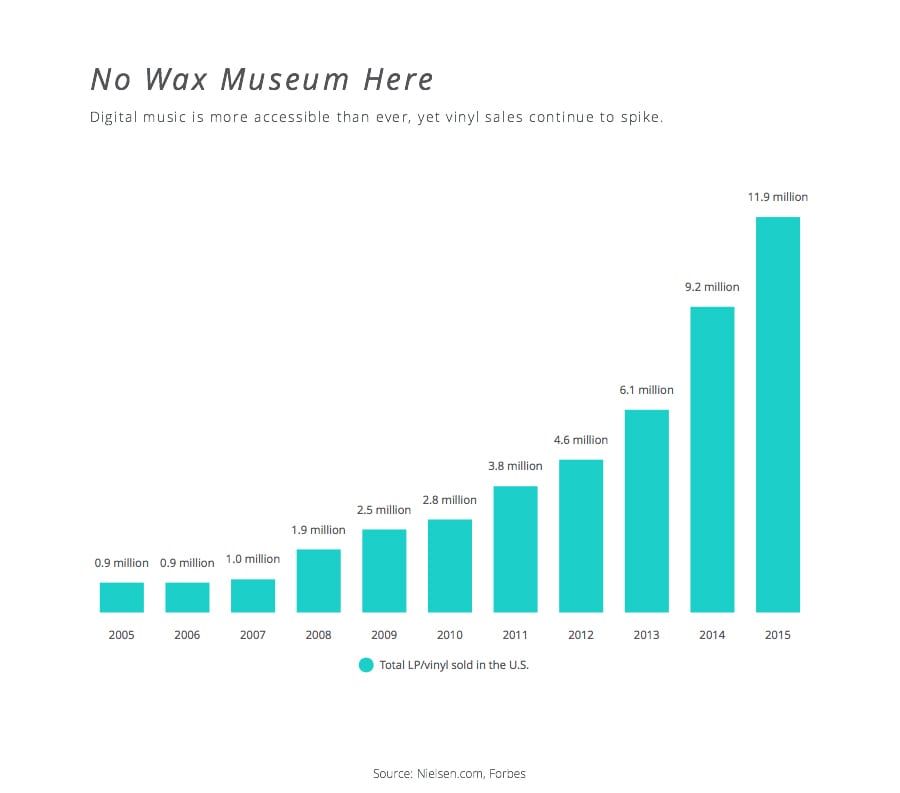

Sympathetic Vibrations | It’s A Groove Thing Despite a momentous shift toward digital music, vinyl sales have enjoyed ten straight years of growth. Why?

(Illustration: Quincy Quagraine for Flatland)

(Illustration: Quincy Quagraine for Flatland)

Published January 21st, 2016 at 2:55 PM

We are currently living in a music consumer utopia.

Services like, Tidal, Apple Music, Spotify, and Google Play offer more than 30 million tracks, available on-demand and anywhere you have a data connection – all in exchange for a monthly subscription price that is less than what you would have paid for a single album 15 years ago. With a smart phone, you can basically fit the entire history of music in your pocket.

The rise of digital subscription services is a product of the MP3 movement of the 2000s, which reduced the once mighty market value of the physical album to pile of rubbled Sam Goodys. And at the time, the public’s light-speed adoption of digital music seemed to indicate that consumers wanted their tunes cheap, convenient, and portable.

Yet, in 2005, a mere two years after Apple’s iTunes Store threw open its digital doorway, sales of vinyl records began to spike. And for ten years straight, those sales have continued to grow.

According to Nielsen Music, the 11.9 million vinyl records sold in 2015 caps off a 1,222 percent increase in vinyl sales over the last decade. In fact, vinyl is the only format that experienced any growth in 2015. CDs and digital downloads faltered, with 10 percent and 3 percent respective decreases in sales last year, while vinyl enjoyed a whopping 29.8 percent increase in sales over the same period.

Lest we fool ourselves, CDs still hold the largest piece of the pie, accounting for nearly 52 percent of all album sales last year. By contrast, despite having the most growth, vinyl sales only accounted for a meager 5 percent of the total albums sold.

Still, despite being a rather small drop in music industry’s bucket, the ever-growing rise of vinyl is an anomaly. Why now? Why, when music consumption is cheaper, more convenient, and more accessible than ever before, is the industry’s most inconvenient, crusty-old-grandpa format enjoying a year-after-year resurgence?

There are many theories. The sucker pick is to put this all on Millenials and their uncanny ability to be unpredictable. But according to Christian Labeau, manager and buyer for Josey Records in the Crossroads, the clientele in his store is as diverse as the collections in the bins.

“We have everything from 13-year-olds coming in here buying their first turntables to 60-year-old guys with audiophile equipment looking for $200 records. At this point, it’s all over the place. It’s not as niche as it used to be,” Labeau said.

Another commonly supported theory is that the music-buying public has a renewed interest in sound quality and that records are the best format out there. It’s not uncommon to hear avid collectors scoff at MP3s and then praise the sound of vinyl using words like “warmth” and “character”.

Sure, to audiophiles used to listening to 200 gram vinyl records through a $10,000 McIntosh stereo system, pretty much everything else out there is going to sound like someone farting into a lead pipe. But to the majority of the music listening public, the difference in audio quality between MP3s and vinyl ranges from miniscule to non-existent, so that theory is out.

One promising possibility is the rediscovery of the value of tangible music. There has been very little discussion about the psychological effect of not really owning your music collection. MP3s and streaming services are avenues built to transfer groups of data that are decoded by your computer or phone to create sound. How can anyone claim ownership of that?

With vinyl, the music is in the actual grooves. You can feel it. And the idea of holding something physical makes the music somehow more real and, therefore, more valuable. According to Mike Russo, co-founder of local independent label, The Record Machine, physical formats will never really go away.

“When I really like a record and put it on for friends, I want to take it out of something and put it on something,” Russo said. “I think there will always be a physical need for music. [Vinyl is] just the one that hasn’t died.”

Perhaps the strongest theory for the rise of vinyl is the experience, which is ultimately an exercise in deliberate action. With a record, you have to seek it out. You have to go through the bins, flip through the records, and find something that excites you in the exact moment. Your choice is obviously affected by your taste, but it may also be affected in your mood at the time. That’s far more personal than using a search engine and hitting “download”. With vinyl you have to commit to your music.

Then when you get it home, you get to engage in the process. Judy Mills, owner of Mills Records in Westport, thinks that experience can’t be replicated.

“There’s nothing like opening up a new record. You’re the first person who’s opened it up and the first person to put the needle on it,” Mills said.

Mills also appreciates that the format forces listeners to hear an entire album in sequential order – something that had been ignored, if not forgotten, as MP3s rose in popularity and making playlists or shuffling tracks became commonplace.

“I’m not a fan of playlists,” Mills said. “Just listening to all the hits keeps you in a certain mental state. It’s not the same as listening to a record and hearing how that music should fit from one song to the next in an album, as the artist intended.”

In the end, it could be any one of these theories or a combination of all of them. And only time will tell whether this decade-long spike in vinyl sales is a silly trend or a serious shift in the industry. Either way, vinyl’s revival signifies a dedication to the value of the creative works of the artists. And if the trend continues, the recording industry could find that its forgotten, crusty-old-grandpa format may be the very thing it needed all along.

— Find Dan Calderon at pdancalderon@gmail.com, or on Twitter @dansascity.