Reducing Kansas City’s Violent Crime Toilet Paper, Shampoo Illustrate Changing Police Tactics

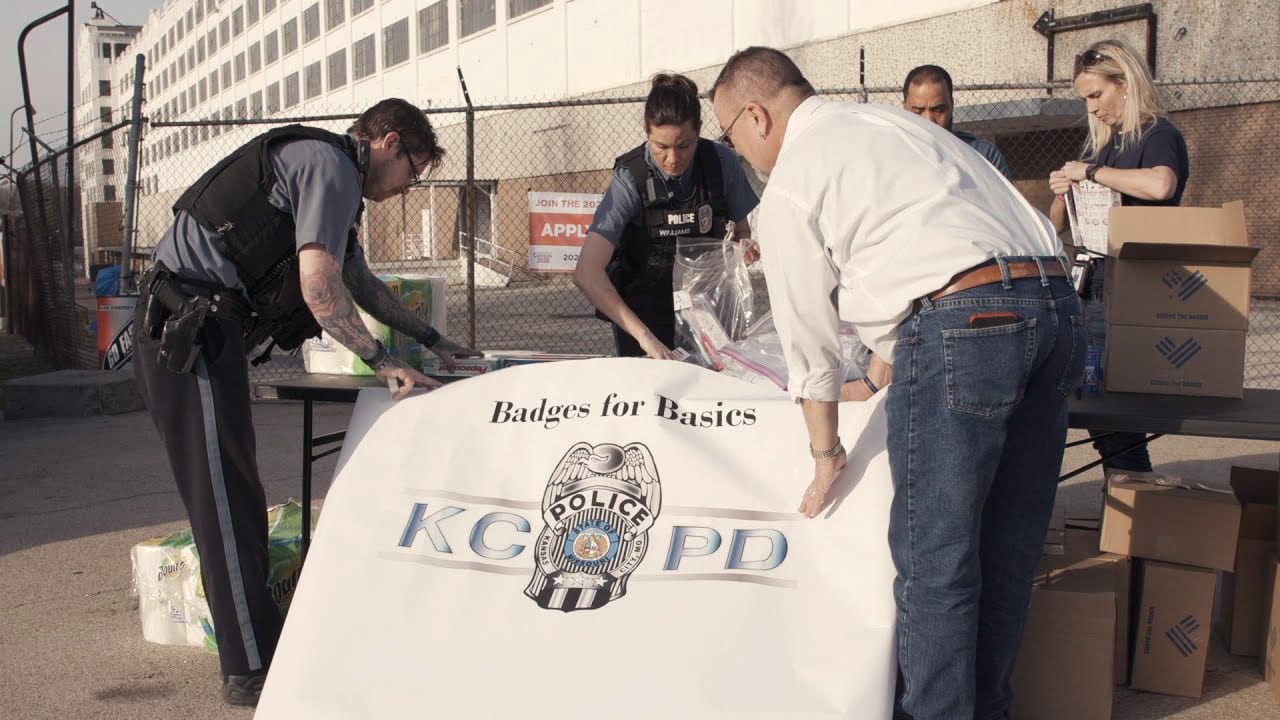

Personnel with the Kansas City, Missouri, Police Department set up for a hygiene-product giveaway in a high-crime part of the city. (Cody Boston | Flatland)

Personnel with the Kansas City, Missouri, Police Department set up for a hygiene-product giveaway in a high-crime part of the city. (Cody Boston | Flatland)

Published April 30th, 2019 at 12:20 PM

This time, Danelle Williams and Vito Mazzara arrived prepared.

The two Kansas City, Missouri, police officers didn’t want to be overwhelmed, like a previous evening last winter, when passersby at 35th Street and Prospect Avenue snapped up their inventory in less than 15 minutes.

On this evening, Williams and Mazzara stationed themselves on a corner in a high-crime area around Ninth Street and Benton Boulevard.

They parked their extended-cab pickup on the grass. It was loaded with more than 2,000 items: full-size bottles of shampoo, conditioner, bars of soap, toothbrushes and paste, body lotion, stick deodorant and toilet paper.

Not exactly a traditional law enforcement approach to countering crime in a city that has one of the highest violent crime rates in the country. But that’s the point.

Police in Kansas City, and elsewhere, are embracing the notion that they can’t arrest their way to a safer city.

The overarching term for this philosophy is called “community policing,” and it can take many forms, such as the hygiene product giveaways. The whole point is to link with the community to attack some of the root causes of crime — be it mental health issues, substance abuse problems or poverty — before they escalate.

Violent crime has, unsurprisingly, emerged as a key issue in this year’s races for mayor and City Council. And increasing the use of community policing is a favored strategy proposed by many candidates, including mayoral hopefuls Jolie Justus and Quinton Lucas.

In that respect, office-seekers are in tune with the leaders of Blue Valley and other neighborhoods in the far eastern portion of the city. These advocates desperately want police officers to better know the neighborhoods and residents they police, instead of racing through the streets from one crime to the next.

The big question moving forward is how will the candidates who emerge victorious after the June 18 election turn the rhetoric into policy. For instance, they will need to work through funding issues with Police Chief Rick Smith, who is a proponent of using social workers and community interaction officers.

Steady Flow Of Customers

Those discussions will come in time, but such policy debates were not the focus of Mazzara and Williams on that chilly Friday night. They had lined up several long folding tables on the sidewalk and arranged the hygiene products in rows. Soon, people started driving up, walking by, curious at first, and then eager for the toiletries.

“How many children do you have?” Williams asked a woman who replied, “four.”

“Here, take some extras,” Williams said as she began picking out lotions and soaps and placing them into a paper grocery sack for the mother, who offered her thanks.

A Somalian grandmother took her bag down the street and began counting the bottles, before sending her grandson back for more. He snagged some extra Kansas City Royals baseball trading cards on his trip back.

A man from Iguala, Mexico, a historic city in the state of Guerrero, wandered by a few times. The State Department is warning U.S. travelers not to visit there. Guerrero is known as one of the most dangerous states, beset with cartels jockeying for control of routes to carry drugs northward.

The man hadn’t found steady work in Kansas City for weeks. The cold weather and the recent snows had affected landscaping and roofing, he said. He gratefully accepted deodorant, shampoo and soap.

One man didn’t want anything from the table. Instead, he requested the phone number of Trena Miller, the social worker who often works with the two officers. He didn’t say why, and they didn’t press him for details. For a year now, each patrol division has been assigned a social worker.

The stock of donated toiletries was depleted in barely two hours. Time to pack up and go.

That night, it was all about being present. Upwards of 150 people, their children in tow, had a positive interaction with police.

The program is called Policing with Compassion and is supported by the nonprofit Giving the Basics, which helped supply the items.

“The need was always there,” Mazzara said. “We just never had anything for it.”

Policing with Compassion is just one way Mazzara and Williams work to deter crime.

Their main role is working as the Crime Free Multi-Housing Unit. The unit’s role is to head off problems that can arise in an area where many residents are renters — either from the approximately 80 apartment complexes within East Patrol’s boundaries or, too often, from absentee landlords who provide substandard housing.

Related Content

Mazzara and Williams sometimes intervene when a tenant is being illegally evicted, and they help property managers and owners deal with residents — or their guests — who might be causing problems for the whole complex.

In addition, they coordinate East Patrol’s Crisis Intervention Teams, officers who are specially trained to recognize and address mental health issues that might be contributing to a person’s erratic behavior. The lapel pins that these officers wear are sometimes recognized by community members in need of assistance.

The officers also advise businesses on how to reduce their vulnerability to crime, such as recommending that convenience stores add lighting and keep merchandise off the floor to deter everything from petty theft to robbery.

The advice is welcomed, even if businesspeople like to keep the cops at arm’s length.

The man behind the counter at a gas station in East Patrol, who identified himself as the owner, said having police around is bad for business, because some customers might have warrants out for their arrest. Nevertheless, the absence of advertising on the windows was evidence he had taken Mazzara’s suggestion to keep a clean line of sight to see who is coming and going.

Time to heal

The officers work 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays.

Because they are freed from answering endless streams of 911 calls, they can spend as much time as it takes at any location.

In one instance, for example, they encountered a wife who begged the officers to move her and her five young children away from an abusive husband. The couple was tight on finances and stressed with extended family also living in their rental home.

Mazzara and Williams encouraged the couple to talk out their issues. It took several hours. No interrupting was allowed. First one spouse could speak and then the other. By the time they were finished, the two thanked Williams and admitted that they’d never heard or experienced the concept of active listening.

A lack of communication skills is prevalent among the Kansas Citians they try to help.

“It’s yelling and screaming, but it’s also generational behavior,” Mazzara said. “We just can’t do policing for that in the same way, and jail is not the answer for everything.”

Williams has personal reasons for bringing a level of empathy and understanding to her work. She has battled post-traumatic stress disorder, partly the result of cumulative traumas during her years of policing.

She studies the psychological underpinnings and physiological reactions of the human body to stress, conditions that are so prevalent in poor communities it’s often termed “toxic.” She’s known to hand out journals to women, encouraging them to write out their feelings as an outlet. Or she’ll discuss meditation as a way to manage stress.

Some people will request Williams. She’s “the bird lady” because of the small black birds tattooed on her hand. She welcomes the trust. She’s happy that, in some cases, this indicates people are more willing than in the past to admit mental illness and their efforts to self-medicate.

“I don’t care if someone is on meth and they call,” Williams said. “You’re not going to jail for being high.”

Williams and Mazzara shrug off guff from fellow officers who think that attitude is merely coddling criminals. The pair never forgets the danger of the streets.

They assume everyone has a gun, because it’s so often true. They’re adept at looking for clues, like when one hem of a person’s baggy pants is about an inch longer than the other. It might be the weight of a gun, tugging the fabric downward.

Mazzara once approached a porch where a man pointed a toy gun, a Super Soaker, at him and threatened to “squirt” him and another officer. He told the man to drop it, and when Mazzara stepped on it, the plastic did not crack. A loaded sawed-off shotgun was inside.

More To The Story

Mary Sanchez is a nationally syndicated columnist with Tribune Content Agency. She has also been a metro columnist for The Kansas City Star and member of the Star’s editorial board, in addition to her years spent reporting on race, class, criminal justice and educational issues. Sanchez is a native of Kansas City.

This year’s municipal elections in Kansas City, Missouri, promise sweeping political changes in the metropolitan area’s largest city. A new mayor and a host of freshmen council members will emerge when the final votes are counted in June. Kansas City PBS will focus its election coverage on three topics that these new elected officials will face: affordable housing, violent crime and business tax incentives. We will tell our stories from some of Kansas City’s most hard-pressed neighborhoods. Keep tabs on our coverage by following us on social at #WhoWillLeadKC