KC Researchers Say Zebrafish May Hold Clue To Reversing Deafness In Humans

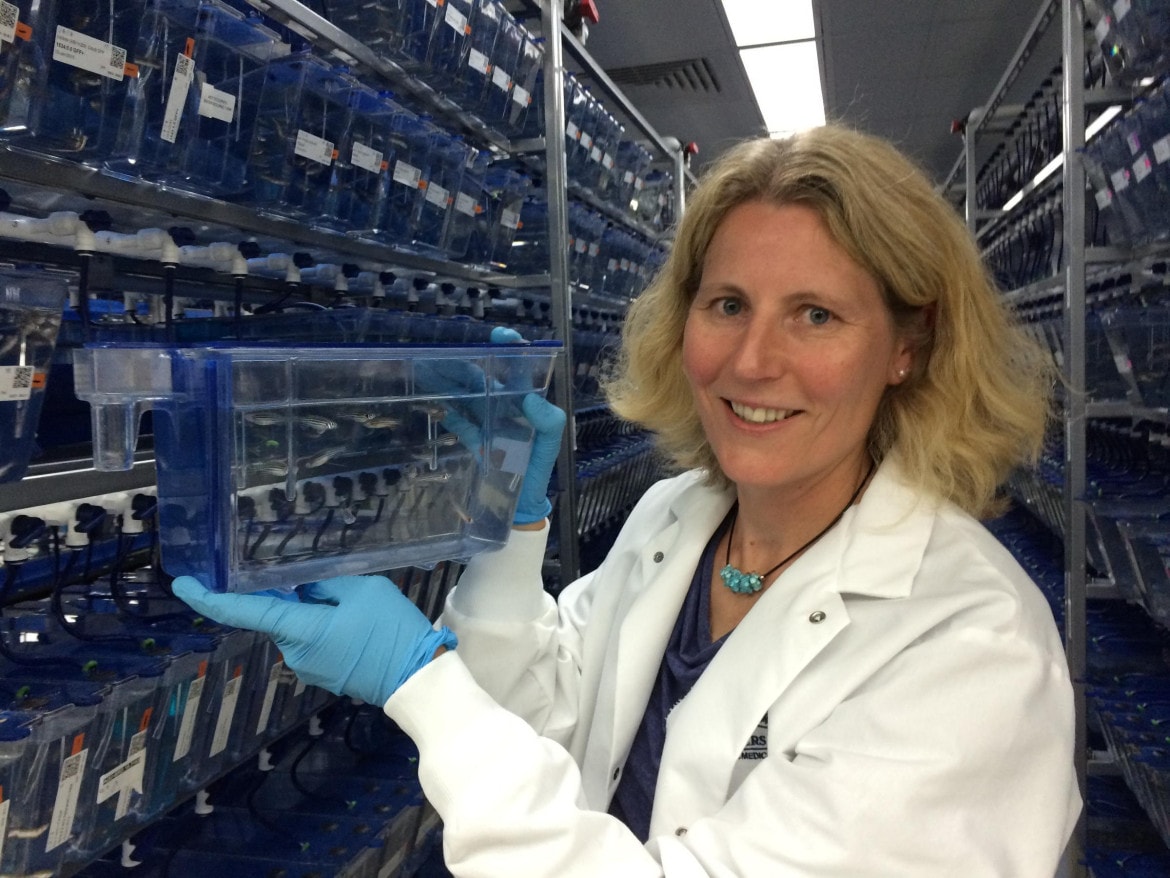

Dr. Tatjana Piostrowski's research focuses on links between the zebrafish and restoring human hearing loss. (Photo: Alex Smith | Heartland Health Monitor)

Dr. Tatjana Piostrowski's research focuses on links between the zebrafish and restoring human hearing loss. (Photo: Alex Smith | Heartland Health Monitor)

Published September 21st, 2015 at 7:00 AM

Early hearing loss was hard for Rob Jefferson to accept, even though it runs in his family.

“No, it couldn’t have been me,” he says. “It wasn’t my hearing. Everybody was mumbling.”

The 56-year-old resident of Belton, Missouri, started losing his hearing when he was 17 years old, the result of premature degeneration of the hair cells in his inner ear.

By the time he reached his mid-30s, everyday communication had become difficult, and Jefferson gradually retreated from social activities.

Rob Jefferson, of Belton, Missouri, began losing his hearing at the age of 17.

(Photo: Alex Smith | Heartland Health Monitor)

“It got worse and worse, to the point where I stopped answering telephones,” Jefferson says. “I stopped going out, because it was easier to stay home in an environment that I could control. So it becomes sort of a self-imposed loneliness.”

When humans lose their natural ability to hear, there’s usually little that can be done, short of resorting to hearing devices. Though it typically happens much later in life than was the case with Jefferson, sensorineural hearing loss – where the root cause lies in the inner ear – affects a quarter of people over age 65. And once the hearing hair cells in the inner ear are gone, they’re gone forever.

At least in the case of humans.

For many animals, however, it’s a different story. They’re able to regenerate lost hearing cells. And at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, researchers are examining how this process works.

Regenerating hair cells

The researchers are among a growing body of scientists who propose that, through the study of animal cell growth, they can learn how to activate similar regenerative abilities in humans and possibly reverse hearing loss.

Deep inside Stowers’ midtown complex, the zebrafish facility is home to about 30,000 tiny striped fish who live in rows of small, square aquariums.

Zebrafish are an ideal species to study, according to Stowers associate investigator Dr. Tatjana Piotrowski, because their embryos are transparent.

“There are really very beautiful organisms under the microscope, because you can see cells move and migrate, how they shape organs,” she says. “You can see the blood flow. You can see the heart pumping.”

Piotrowski recently co-authored an article in the journal Developmental Cell that describes the cellular communication process that occurs when hair cells die and are regenerated in zebrafish.

She explains that the zebrafish hair cells she studies, which grow on the side of the fishes’ bodies, are remarkably similar to human hair cells but aren’t used for hearing.

“Here it’s not sound waves, necessarily, that activate this motion, but it’s water motion,” Piotrowski, who grew up in Germany and speaks with a slight accent, says. “So fish swim in their environment, and there’s a fish next to them or there’s an object in the water – they can perceive that.”

Human hair cells, which number about 32,000 in infants, can be permanently damaged and eventually killed by exposure to loud noise, certain antibiotics and chemotherapy treatments, resulting in hearing loss and even deafness.

Gone but not gone

But in zebrafish, the support cells that surround hair cells have the ability to divide and transform when hair cells are lost.

Seen here are the sensory organs of a zebrafish embryo. (Credit: Tatjana Piotrowski |Stowers Institute for Medical Research)

“You can imagine that some of these support cells act like adult stem cells in the sense that they are like a reserve pool of cells that, when they are needed, they turn into a hair cell,” Piotrowski says.

Piotrowski’s research details which support cells turn into hair cells and describes how signals within the cells inhibit or promote hair cell regeneration.

The work of her lab has won the admiration of Dr. Edwin W. Rubel of the University of Washington, a pioneer in this area of research.

He calls the Developmental Cell article “a beautiful study.”

In the late ’80s, Rubel and fellow researchers working at the University of Virginia made an unexpected discovery while studying dead hearing cells in baby chicks.

“Cells that were dead and gone weren’t still gone,” he says. “They seemed to be there, which surprised us greatly. In fact, it took us repeating the study three times in order to believe it.”

Evolutionary trade-off

Researchers have since found that lots of animals can regrow these hair cells, but Rubel think this ability was given up by mammals as part of an evolutionary trade-off.

“We haven’t seen reasonable amount of regeneration in any mammal,” Rubel says. “I believe this is something that was lost along with the development of high frequency hearing.”

By studying how zebrafish and chicks regenerate hair cells, Rubel, Piotrowski and others hope to map out how humans’ regenerative abilities might be triggered with the help of drugs.

Those hopes have been bolstered by the discovery that mice embryos show some limited capacity for hair cell regrowth.

There are still lots of questions in the field about how the cell systems work. And it’s unknown at this stage to what extent hearing could be restored. But for Ed Rubel, the research is worth it.

Just as people can regenerate skin and fingernails, Rubel is convinced that regeneration of hearing is a human capacity that simply needs to be unlocked.

“This is a latent ability. There’s plenty of evidence that there’s cells in the neonatal cochlea and maybe cells in the adult cochlea, or vestibular organs, that can be induced to make new cells or regenerate or to transform into hair cells,” he says.

That’s good news for people like Rob Jefferson, who are eager to regain their lost hearing.

Jefferson actually regained his ability to hear when he was 55, with the help of cochlear implants.

After years of isolation and feeling out of touch, he says, getting his hearing back turned things around for him.

“I’ve got my life back,” Jefferson says. “And that’s what I needed.”

— Alex Smith is a reporter for KCUR, a partner in the Heartland Health Monitor team.