Mending Our Broken Heart: With Region’s Health at Stake, Leaders Seek Downtown Rebirth

Published September 23rd, 2022 at 11:30 AM

“Downtown KC: Mending Our Broken Heart,” was a groundbreaking series originally published by The Kansas City Star 20 years ago this month.

It was written by former staffers Jeffrey Spivak, Kevin Collison and Steve Paul, with photographs by Rich Suggs. It was edited by former deputy national editor Keith Chrostowski.

CityScene KC thanks The Kansas City Star and Mike Fannin, its president and editor, for granting permission to republish this report.

While The Star retained the text of “Mending Our Broken Heart,” the original photos and graphics were unavailable. Photos of that missing material from a reprint of the series were used as much as possible.

Ask many urbanites or suburbanites whether downtown Kansas City still matters in their lives, and their answer is chilling: No.

Northland resident Ken Jenkins worked downtown for a decade, but now he can’t remember the last time he went there.

“I couldn’t care less about downtown,” the local native says.“There’s nothing to go there for. All the personality is gone.”

Likewise, when an opinion poll conducted for this story asked area residents for the first word that came to mind about downtown, the most common answers included “dead,”

“nothing” and “empty.”

Should this matter? That is, with the Country Club Plaza booming and many suburbs growing, why should we even care about downtown anymore?

Because downtown means more to our region than many of us realize.

Business leaders will point out, of course, it’s this region’s economic engine, with 107,000 jobs and one-third of the overall office market. And civic boosters will tell you it’s this region’s heart and soul, our historic center and our gleaming skyline. It’s our face to the world, giving tourists a first impression of how our entire metropolitan area is faring.

All true. But there’s more. Even if you live in Liberty, Lake Winnebago or Lenexa, downtown’s woeful present and precarious future are more than just a matter of civic pride or someone else’s job.

Downtown’s sickly state probably is taking money out of your pocket. Its failings may be limiting your job opportunities and hobbling our ability to maintain the culture and quality of life that once made us “one of the few livable cities left.”

A view of the South Loop area of downtown in June 2003 before the revitalization effort led by former Mayor Kay Barnes began. The chair sets in the middle of where the Sprint Center is now located, the buildings in the background along Grand were demolished to make way for the Power & Light District. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Bruning)

After all, we’ve ignored just about every significant downtown trend across the country. We didn’t build some sports palace. Or light rail. Or an entertainment complex – that one died when the plug was pulled on the Power & Light District.

Now we’re paying the price.

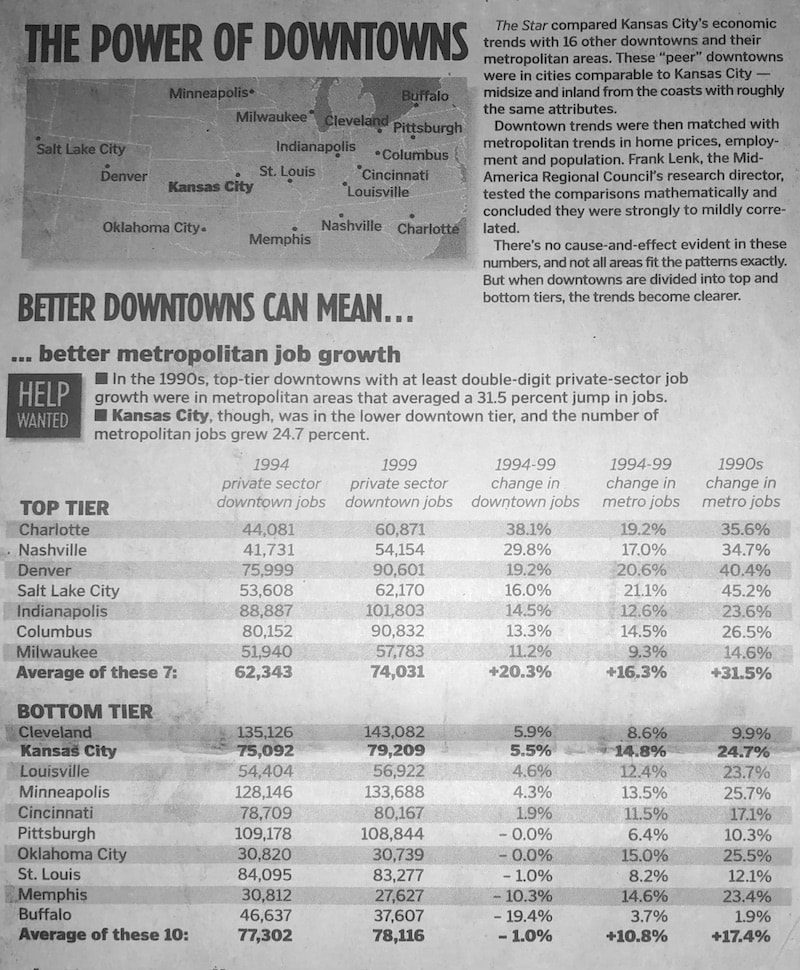

No experts have probed deeply enough into metropolitan relationships to prove that the well-being of suburbs depends on downtowns. So The Kansas City Star analyzed a raft of indicators from the downtowns and suburbs of 16 cities that compete with us for businesses and people – places considered our peers, such as Indianapolis, Louisville and Denver.

The newspaper’s research uncovered definite, and alarming, patterns:

Those cities with faster-rising downtown populations enjoyed, on average, faster-rising home values across the entire metropolitan area.

Those with stronger job growth downtown showed, in most cases, stronger areawide job growth and population growth.

And those with better downtown job growth tended to have better metropolitan economic growth, too.

All these indicators point in the same direction: A healthier downtown makes for a healthier metropolitan area. And in all the comparisons, Kansas City’s downtown lagged. So our suburbs did, too.

“Identities of cities and metropolitan areas have always been based around a center, a downtown,” says Thomas McDonnell, president of DST Systems Inc., a financial data services company downtown. “For this metro area to succeed, its center

must succeed.”

Yet the sad truth is downtown Kansas City in the past decade hit perhaps its lowest point.

Its residential population bottomed out.

Its share of the metropolitan office market has reached a new low. Its taxable private-sector property values are dropping, as measured by government tax assessments. This past summer, city voters wouldn’t approve a bond issue to start spiffing downtown back

up.

But if downtown is a patient with a ravaged heart, it still shows signs of vitality. DST has improved much of the west end. Union Station has reopened. New loft housing projects are

announced almost every month. The Crossroads district has emerged as a funky art enclave. And a performing arts center is on the drawing board.

Indeed, the time is right, civic and political leaders contend, to accelerate this recuperation. Downtown, they believe, has reached a turning point. So they’re considering a blur of ideas and plans. The emerging vision avoids replicating our grandparents’ downtown, dominated by the office and retail scenes, and instead calls for remaking it as a hip urban neighborhood.

Our leaders believe it needs more residents and more visitors, more job opportunities and more night life, plus simpler things like cleaner streets. It needs all these things, or more families could feel the heartache of a son or daughter leaving the Kansas City area because downtown doesn’t measure up.

Fans enjoying one of the bars in LoDo outside of Coors Field in downtown Denver.

Erin Wysong, for instance, grew up in suburban Johnson County and cherishes its family-friendly environment. After graduating from college, though, she moved to Denver – without even having a job.

“Denver seemed like there was a lot going on for younger people,” Wysong says. She now lives near the center of town, walks on a trail that winds past the skyline and often heads downtown for happy hour or a show or a game.

Kansas City’s downtown, she says, “is not a place for me in my 20s.”

For her parents, “That means our grandchildren will be out of town,” says her father, David, a former Johnson County commissioner. “And I know a lot of people like this.”

Nothing of interest

It’s easy to understand why young adults would feel the way. Erin Wysong does.

Downtown Kansas City, stretching from the Missouri River to 31st Street and the BMA Tower, has shrunk from 32,000 residents to 6,300 in the last half-century. During that time, too, it’s gone from having about 450 bars and restaurants to fewer than 150. It’s gone from roughly 175 hotels to 10. From 41 colleges or trade schools to five.

When The Star’s poll asked 608 residents in the five-county area about downtown, half of them said they didn’t go there more than once or twice a year. And when they were asked why, their top answer was: “nothing that interests me.”

Janice Vaca remembers growing up on the West Side in the late 1960s and her mother taking her downtown on Saturdays to a movie or to shop at Macy’s or the Jones Store or the Kresge dime store. Now, she’s a mother living in Lenexa and goes downtown just once a year, for a trade show at Bartle Hall.

“My husband grew up in the same area, and he and I, we talk about it all the time, all the things we used to do,” Vaca says. “Now there’s nothing to take you there anymore. It’s a shame.”

Without a doubt, our downtown doesn’t measure up.

Among our 16 peers, stretching from Charlotte to Salt Lake City, from Minneapolis to Oklahoma City, Kansas City’s downtown fell below average – ninth in private-sector jobs and 10th in population.

We fared even worse in other benchmarks of downtown life. We’re among the worst in office vacancies. We’re the only one without a sports stadium or modern arena downtown. And we’re one of a handful without a multipurpose performing arts center or even a popular nightclub district there.

The former Empire Theater was in tatters when this photo was taken in 2006, its exterior boarded up, its interior in ruins and trees growing from its roofop. The building was considered a prominent symbol of downtown’s decline. (Photo by Len Fohn)

When Ernst & Young recently brought a motivational speaker to its offices in the One Kansas City Place skyscraper, the speaker asked the assembled employees where everyone went after work on Fridays. Any special events? Any hot spots nearby? The employees stared back with blank faces.

“That’s because there’s nowhere to hang out, really,” says Richard Schapker, a technical writer for the firm. “There’s not a whole lot around this area.”

An areawide concern

But there should be, because downtown is the bellwether of our well-being.

The Star analyzed how downtown population and job growth related to areawide home values, population, job growth, even economic growth. This was done with our 16 peer cities – all inland, midsize metropolitan areas with roughly the same attributes.

Downtowns were defined by the downtown agency in each city. Kansas City’s downtown, for instance, generally followed boundaries adopted by the Downtown Council: from the river to 31st Street, with highways generally on the west and Troost Avenue on the east except at the north and south ends, where it’s Locust Street and Gillham Road respectively.

In examining our 16 peers, The Star found that wherever downtown employment surged, metropolitan employment and population typically surged, too, and so did the metropolitan

economy.

From 1994 through 1999, metropolitan areas with the best job growth downtown also added jobs overall at a better rate – 51 percent better. In those same areas, the overall economy grew one-third faster from 1991 to 1999, and the overall population grew three times faster during the entire decade.

Kansas City had one of the slower-growing downtowns. In all likelihood, that sluggishness was costly.

If Kansas City’s downtown had added jobs in the 1990s like Charlotte’s or Denver’s or other top performers’, metropolitan Kansas City could have produced an extra $5.4 billion in gross metropolitan product, a measure of economic output. Seen another way, metropolitan Kansas City could have added 53,400 more jobs – a full one-fourth more than actually were created in the 1990s.

Just this spring, Washington Mutual, a giant financial services company, was looking to consolidate loan offices in different regions. The competition for 220 jobs came down to Kansas City and Dallas. The company chose a Dallas suburb for several reasons. One of them was a “high quality of life,” including “access to arts and culture,” according to Stuart Miles, a Washington Mutual executive.

That, in corporate speak, means our downtown didn’t cut it.

“Arts and culture usually translates to an urban environment, and that’s why we need a vital downtown,” says Blake Schreck, who as president of the Lenexa Chamber of Commerce had a role in trying to recruit Washington Mutual. “Those kinds of things make a difference.”

In another bond between downtown and metropolitan progress, The Star found that home values typically rose faster in metropolitan areas whose downtowns had the highest residential densities. That also held for areas with downtowns that had the fastest-growing populations.

In the 1980s, housing appreciation in metropolitan areas with fast-growing downtowns rose at a 50 percent higher rate than in areas with slow-growing downtowns. In the 1990s, the difference was much greater, more than double. This indicates that the relationship between downtowns and metropolitan housing prices grew stronger.

In Kansas City during the 1980s and 1990s, downtown remained on the small side, and metropolitan home values grew slowly.

So if someone in the metropolitan area bought a $100,000 house in 1990 and sold it a decade later, the sales price probably would have been about $157,000 – not a bad profit and easily outpacing inflation. But with more people living downtown, data from other cities suggest, that price could have been $15,000 more.

“I think that’s significant, and that’s something people can understand,” says suburban Platte County Commissioner Michael Short.

Kansas City’s boosters often tout our housing affordability. But there’s another side to that. Typically, metropolitan areas with hot housing markets – like Denver, Salt Lake City, Portland and Minneapolis – also are places with hot downtowns and hot economies.

“A healthy downtown draws more people to a region, and that fuels demand for housing,” says Frank Lenk, research director for the Mid-America Regional Council, Kansas City’s metropolitan planning agency.

The connections between downtowns and their suburbs are complex. While numerous studies have found bonds between urban cores and their suburbs, narrowing the urban focus to just downtowns presents more difficulties, and academics haven’t yet put their arms around that statistical relationship. So The Star showed its research to several experts like Lenk across the country. They all agreed with the findings.

“It’s interesting new data,” says Robert Lang, director of the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech University. “There are definite parallels.”

Outside academia, however, few people accept that connection. In The Star’s poll, a majority of respondents felt downtown had no impact on their neighborhoods or livelihoods. After all, downtown Kansas City represents less than 1 percent of the metropolitan population and 10 percent of the metropolitan jobs.

Outside academia, however, few people accept that connection. In The Star’s poll, a majority of respondents felt downtown had no impact on their neighborhoods or livelihoods. After all, downtown Kansas City represents less than 1 percent of the metropolitan population and 10 percent of the metropolitan jobs.

Some contend that top-performing downtowns simply benefit from suburban prosperity. That’s what Johnson County Commissioner George Gross concludes: “There does not seem to be any evidence … that development in Kansas City’s downtown has more of an effect on the economic vitality of the suburbs than development in Overland Park or Spring Hill

does.”

Not everyone in suburbia agrees. Says Liberty Mayor Stephen Hawkins, who has worked downtown: “It is clearly a center of gravity. When you have such a concentration there, you can have other things elsewhere. You can have places like Liberty.

“You can’t have a metropolitan area unless you have a center.”

Cautionary tales

Downtown’s importance can be traced not only through numbers, but also through people – such as those who choose not to live here.

Aaron Ellison grew up in Kansas City’s historic Santa Fe neighborhood, graduated from Lincoln Prep and eventually from the University of Missouri’s medical school in Columbia. Last winter, as his residency approached, he weighed where to start his career.

Ellison wanted an urban environment, a place with eateries and clubs where African-Americans socialized. How about his hometown?

“What I was looking for,” he says, “I didn’t feel Kansas City offered.”

He chose Charlotte.

“They have a very vibrant night life downtown,” Ellison says. “Downtown is one of the places where people hang out.”

Such decisions are cautionary tales for Kansas City’s entire economy.

Consider the so-called new economy. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development found that 40 percent of high-tech jobs created in the middle to late 1990s went to the urban parts of the nation’s metropolitan areas. Urban Kansas City, though, landed just a quarter of new tech jobs created in the area.

When the tech boom began, some business analysts claimed cities were no longer important. Workers could hook up their laptops from anywhere, like home. But more recently, academics like Carnegie Mellon University’s Richard Florida are asserting that place still matters. In his view, “creative-class” workers, from software engineers to theater directors, are drawn to hip, eclectic environs with coffee shops, cafes, bike trails and lively streets.

So a more magnetic downtown could help recruit talent here – such as to health-tech giant Cerner Corp.’s campus just north of downtown.

“For the younger professional, we need to have places we can take them,” says Julie Wilson, director of strategic staffing at Cerner, which expects to add a couple of thousand jobs in the next few years. “Night life is important, the social aspects are important. It’s part of what candidates evaluate.

“There have been important improvements in the River Market, with all the lofts being built there. The more we do that as a city, the more attractive we’ll become to the kinds of talent we want to attract here.”

Not all businesses, however, recognize downtown’s allure.

Midland Loan Services, for instance, left downtown this year partly because it needed more parking. In the process, it lost one of its newest employees, 23-year- old credit analyst P.J. Ventola. He wanted to stay downtown, and rather than move with Midland to Johnson County, he moved away – to California.

“I love downtown,” Ventola said before leaving town, “but the opportunities for young people downtown are getting smaller and smaller. The businesses keep leaving.

“Downtown is really sad right now.”

Signs of change?

Ventola is far from the only one who feels that way. Downtown may matter to the metropolitan area, but it leaves a bad impression on many people.

That’s clear from The Star’s poll. When residents were asked for one word to describe downtown, their reaction was almost hostile: Negative images like “bleak,” “crummy,” “deserted” and “wasteland” outnumbered positive ones by a ratio of 8-to- 1.

On summer Saturdays, the bustling City Market, with its produce and knickknack vendors, stands out as a bright spot in Kansas City’s largely desolate downtown.

One word hardly captured the shame and contempt that some poll respondents felt. Listen to Skip Boyd from Gladstone:

“It makes me sick every time I go down there,” says the vending machine entrepreneur, who services machines downtown every week. “People like to walk down the streets and see activity and look in windows and see things. They like to be part of a crowd. But there is no crowd downtown.

“That’s why it’s a disaster.”

And it’s not just locals who feel that way.

This summer, Judy Brown arrived at the Kansas City Marriott Downtown on a Saturday night for a conference. She went out to find something to eat, but found all the restaurants closed. Themnext night, she walked for blocks around the hotel looking for a club, but couldn’t find one.

“Coming here, you’re thinking the conference is in a prime spot, downtown,” says Brown, who works in downtown Minneapolis. “But then you get here and you wonder, ‘How can this be an urban city?’

“It gives the impression the whole city’s dead.”

And that impression isn’t just made because there’s not much to do downtown. It’s also because of what visitors see while looking for places to eat and drink: Empty streets, vacant storefronts and boarded-up buildings – particularly in the area long shadowed by the ill-fated Power & Light District.

“The result is tragic,” says Phil Kirk, chairman of MC Real Estate Services Inc. and retired chairman of DST Realty. “It would be like carving out your front yard and living room and leaving them in terrible shape, then having guests over to your home. Of course they would have a bad experience.”

For those who venture outside downtown’s ailing heart, however, the experiences – and impressions – can be different.

Check out the Crossroads district every first Friday of the month, when new art exhibits open and crowds trek from gallery to gallery. Or wander the City Market on Saturday mornings, when thousands of shoppers roam aisles of produce and knickknack vendors. Then there’s Union Station, which has reclaimed its status as a community gathering place.

“Downtown isn’t dead,” contends R. Crosby Kemper III, the latest Kemper to lead UMB Bank. “Look at the Freight House; it has three great restaurants. Union Station is a destination. The River Market; lots of people are moving in down there. It’s a pretty hopping place.”

First Fridays trace their beginning to around 1999 when Crossroads gallery owners agreed to host a low-key joint open house, by 2019 the event had grown to attract 20,000 people.

There’s more happening:

Hundreds of new loft apartments are being built in the loop, and old skyscrapers like the twin-spired 911 Walnut are being considered for apartments, too. The President Hotel is being renovated. A few new music clubs have opened. The Star announced plans for a $200 million press plant.

And Mayor Kay Barnes is touting a “SoLo,” or south loop, cluster of housing, working, eating and shopping destinations for the area that was to have been the Power & Light District.

If even more were going on downtown, people would go there more. People like Michael Gallagher of Lee’s Summit. He grew up in Kansas City, then spent his career in other cities.

But when he retired, he came back, to be near family and because of our vaunted low cost of living. He’s single and goes out a lot – but not downtown. He only gets there every couple of months, to see shows at the Music Hall.

“I’d love to be able to come downtown more often,” Gallagher says. “If we want to compete with other cities and attract a national or international following, our downtown needs to be

vibrant. It needs to be alive.”

A new approach

It can be done.

Just look at some of Kansas City’s peers. Denver’s downtown came back from the dead and now is a hot neighborhood. Pittsburgh created a downtown cultural district even as the rest of the city and area withered. Milwaukee’s downtown businesses joined together to make improvements. Leaders in Memphis created a downtown development authority, just as Kansas City has done, and it helped spur investment there.

Kansas City is learning from them. Over the next several weeks, The Star will publish a series of reports exploring what other cities have done with their downtowns and what local leaders want to do with ours.

In the past, planners here pinned downtown’s hopes on grand edifices – an expanded convention center, an indoor mall, skyscrapers, hotels and museums. They turned out to be isolated fortresses, with gaps left between them.

Now Kansas City’s civic and political leaders are embracing a new approach. It’s designed to fill in the gaps downtown and build on the current momentum toward loft-style housing and a lively arts scene.

So it calls for thousands more people living downtown, to give the streets some life. It calls for more draws like a performing arts center and public festivals, to beef up the demand for restaurants and nightclubs.

It calls for sprucing up the streets and adding more parking, to relieve visitors’ greatest gripes.

And it calls for better downtown leadership, to get these things done.

Doing just one of these things won’t be enough. The ultimate goal is restoring that elusive element known as ambiance, and based on what’s happened in other successful downtowns, that goal requires all of the above and then some.

As out-of- towners Curtis Johnson and Neal Peirce urged in a recent Citistates report on Kansas City’s strengths and weaknesses: “It’s time to build a downtown that exhibits true soul – a place that is well-maintained and offers a welcoming spirit, scale, interest and true liveliness.”

Plenty of local people certainly feel that way, too. In The Star’s poll, an overwhelming 87 percent of metropolitan area respondents said downtown needed to be revived. That view is shared by local power brokers such as Mayor Barnes, whose administration has made downtown a priority, and the Civic

Council of top executives, which paid for the creation of a new downtown master plan.

“We have the vision now,” Barnes says. “We have a critical mass of people and organizations who are committed and…making momentum that perhaps hasn’t been there before.”

But plenty of people are losing patience. When The Star’s poll asked area residents whether political and civic leaders were doing enough to revive downtown, almost 80 percent of

respondents answered with a resounding “No.”

So Kansas City is at a crossroads. For decades now, it’s been losing ground in the ranks of great American cities. And today, more than ever, metropolitan areas are competing for momentum, for attention, for stature, for jobs and the people to fill those jobs. What cities are like as places makes a difference.

In metropolitan Kansas City, we don’t have oceans or mountains or eternally sunny skies to attract people. But we can fix our downtown.