‘Talking Scripture’ explores sacred text and meaning through interfaith dialogue

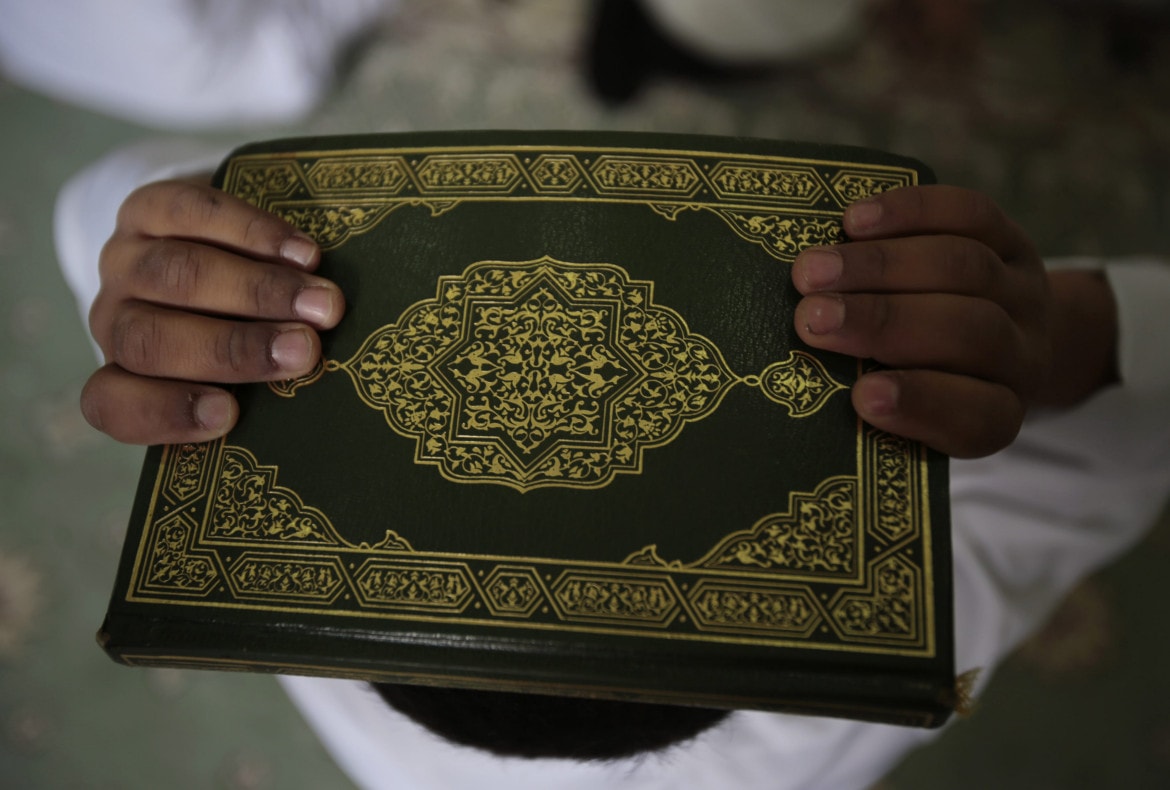

The Quran, Islam's holy book (Photo: Hasan Jamali| AP)

The Quran, Islam's holy book (Photo: Hasan Jamali| AP)

Published October 27th, 2015 at 4:07 PM

Two pastors, a pair of religious scholars, a Muslim, and a Baha’i lawyer sat down on the stage of a UMKC auditorium recently to chat. And no, this is not the set-up of a joke: It is the actual panel of interfaith leaders that led a thoughtful discussion on scripture and its meanings in our culture last Thursday.

Hosted by American Public Square, the panel was made up of academics and local religious leaders, including University of Kansas religious studies professor Molly Zahn; acclaimed Vanderbilt divinity school Judaism scholar Amy-Jill Levine; University of Nebraska law professor Brian Lepard, who also serves as a Baha’i specialist for the United Nations; Al-Haqq Islamic Center Imam Sulaiman Z. Salaam; and Metropolitan Missionary Baptist Church’s Rev. Wallace Hartsfield II. Presbyterian pastor Brian Ellison, executive eirector of the Covenant Network of Presbyterians, moderated the discussion.

Most of the conversation was spent on a deceptively simple story: the parable of the good samaritan. Many of us know the Luke 10:25 verse about neighbors. The scriptural passage appears to have a very digestible message.

In the hands of these religious scholars, however, the story exploded into a network of meanings.

If you don’t know the passage, here’s a quick summary: Robbers attack a traveling man, leaving him severely beaten, and two individuals walk right past him before a third offers him assistance and appears to save his life.

Cue the “do unto others” challenge. Insert the golden rule here.

Clear cut, right?

“I’m struck by the setting in which the story is placed,” Hartsfield told the gathering of about 150 at UMKC’s Pierson Auditorium. “It’s in this space of liminality, in between Jericho and Jerusalem. … It takes place in this area that seems to be in this difficult and challenged area, but you have this neighbor that appears in this setting.”

Hartsfield’s congregation, located near the intersection of Linwood Boulevard and Prospect Avenue, serves an area of KCMO that’s likely to garner an ungenerous set of assumptions.

“My neighborhood is often referred to as ‘the ‘hood,’” he said. “It’s interesting that one takes the ‘neighbor’ off the ‘hood’ and it just becomes ‘the hood.’”

Hartsfield wasn’t just playing with words. The evening’s discussion focused on scripture and textual — religious forces inherently composed of language.

“Here you have a parable that challenges where a neighbor is most needed,” said Hartsfield. “Really where the demonstration of where neighborliness takes place is in those areas where it has just become ‘hood.’”

“I would offer that the activity of a neighbor is most demonstrated in those challenged areas that are just ‘hoods,’ in between,” he said. “You need a neighbor in order to make it a neighborhood.”

Imam Sulaiman Z. Salaam offered a saying about Islam’s sacred texts, which could be applied to all scripture: “Each verse of the Quran, it’s like an onion … with multiple layers.”

It’s more than just an analogy. Salaam said Muslim tenets include commandments to study the New and Old Testaments, and in fact many of the same key stories from the Bible, like that of Cain and Abel, appear in the Quran.

Salaam offered a comparison between the Muslim text and the Jewish sacred texts’ original form. That led the conversation into an exploration of a sacred book’s relationship to divine speech, and, more broadly, a believer’s relationship to a book, all of which is mediated by language and meaning.

“It’s basically saying this is someone’s interpretation of it,” said Salaam. “You may be right, and you may not always be completely wrong, but God guides.”

The stakes are high in scriptural interpretation and the religious consequences of the meanings gleaned. Zahn spoke about the deep rifts that the issue of slavery caused 19th Century Protestant communities, specifically because of the religious justifications that it did or did not have, depending on who you asked.

“You have people essentially quoting the Bible at one another, saying, ‘Slavery is antithetical to the Christian faith’ … and you have other people on the other side saying the Bible supports the institution of slavery,” Zahn said.

“The foreignness of that debate to us now shows how people’s perspectives inevitably change, and how the scripture does involve human viewpoints that change over time,” she said. “That means there will continue to be debate as culture changes and society evolves … about the proper interpretation of some of these issues.”

“Now, my personal opinion about believers and members of a faith tradition, we have to be willing to … argue with God and say, ‘I don’t think that’s right,’” Zahn said.

There is a not-dismissable part of religion itself that’s a sort of snow globe, a small thing pretending to be a large thing, or maybe everything. It’s a thing busy with activity wildly spinning in a small space, pretending to be large and more total than it is.

Ellison said the dialogue on the stage Thursday night bore consequence to some of those questions of ultimate significance.

There is a not-dismissable part of religion itself that’s a sort of snow globe, a small thing pretending to be a large thing or maybe everything.

“To a degree, all religions try to answer questions of importance, the meaning of life, and the meaning of death,” Ellison said. “I think what we believe about scripture is going to have an impact on what we think about those things.”

In other words, whatever the scholarship or whatever the teachings are, it’s about the individual and their assertion of the truth of a belief through their lives and actions.

Seen this way, the act of belief is a creative act, as well an intellectual and spiritual one.

“From my perspective as an informed, Protestant, Presbyterian, Christian,” said Ellison, “what we are certain of is that God creates humanity to be in relationship (with him).”

“That is, we don’t exist unto ourselves,” he said. “We exist in community with God.”