A Love Story: Football, the NFL, the Chiefs and Kansas City Chiefs Founder Lamar Hunt Would Be 'Over the Moon' About the NFL Draft

Published April 27th, 2023 at 6:00 AM

Above image credit: GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium will host what will likely be one of the coldest NFL games ever played in Saturday's AFC Wild Card game between the Chiefs and Dolphins. (Courtesy | Kansas City Chiefs)Lamar Hunt, who brought the Chiefs to Kansas City 60 years ago, started scrapbooking as a boy.

Cutting and pasting in the 1940s, he clipped articles from newspapers and photos from magazines, reassembling ephemera devoted to the football stars of his youth and completing a personalized version of a widely shared public passion.

Soon after moving the Dallas Texans football team to Kansas City in 1963, Hunt did something similar, but on a much grander scale.

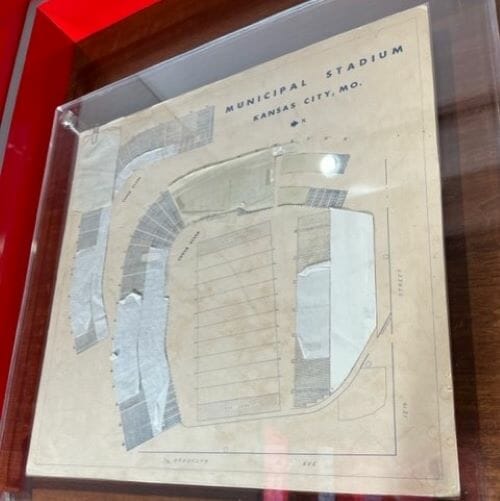

Taking a seating chart of Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium and using scissors, paste, paper clips and sheer paper, he moved this here and that there, re-configuring a community space that by then had hosted professional sports for 40 years and made it — as Kansas City fans enjoying singing before every game — the home of the Chiefs.

“This is something you would see a young boy do in the 1940s or 1950s,” said Bob Moore, Kansas City Chiefs historian emeritus.

“But he kept that same thought process his entire life. At his office in Dallas, he would move from table to table, filling up one, then leaving a note that said, ‘Don’t move anything,’ and then moving on to another.

“He would take things and try to make something out of them.”

The Stadium Experience

As multitudes gather this week for the NFL Draft, the stadium experience Lamar Hunt imagined for Kansas City will manifest again.

Only this time it will feature a 378-foot by 176-foot temporary stage at the south doors of Union Station that, together with the National WWI Museum and Memorial’s surrounding lawns, will resemble an immersive gridiron theme park.

But if Kansas City today shares the same intense fascination with pro football that Hunt did, it first had to work through its complicated relationship with the game itself.

Beginning in 1891, fans of the squads fielded by the universities of Kansas and Missouri gathered almost every fall In Kansas City through 1910 to watch the annual game between the two schools.

In contrast, some considered professional football the low pursuit of mercenaries.

Then there was the way the game sometime was played by college and high school students, with minimal protective gear or violent “flying wedge” formations that led to death and serious injuries across the country.

The game was so violent that Kansas City high school officials largely banned the sport from 1905 through 1918.

But, after many thousands of American men played on military teams while training for World War I, the sport’s image improved, with Kansas City’s first NFL franchise debuting in 1924.

When the team ceased operations two years later, voters nevertheless in 1931 approved a $750,000 bond issue to finance a new stadium.

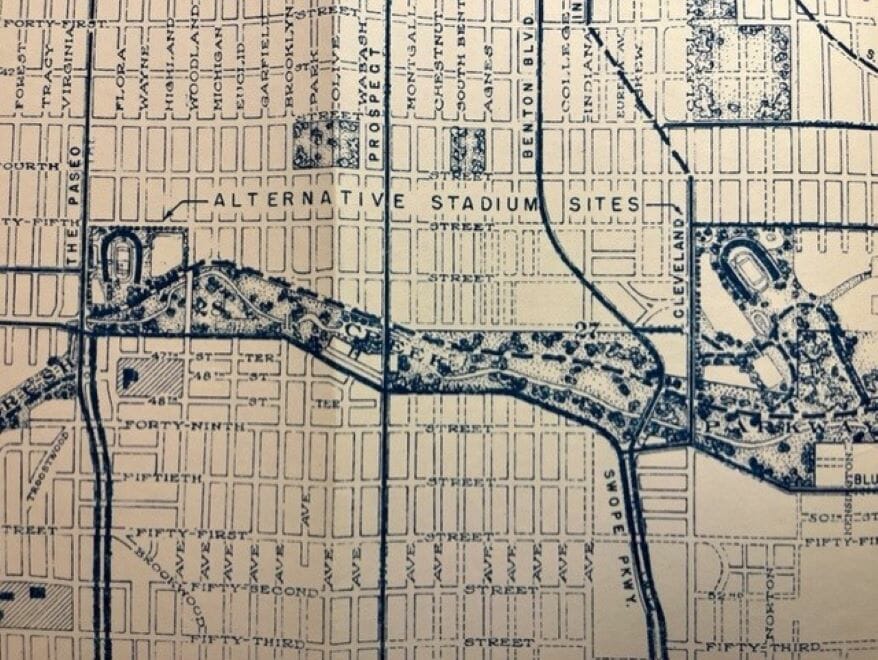

While city officials never built that facility, members of the Kansas City planning commission doubled down at the end of World War II, submitting a 1945 study promoting a new horseshoe-shaped stadium built with football in mind at one of two possible sites just north of Brush Creek.

Kansas City never built that stadium either.

But voters spoke in 1954, enticed by the possible sale of the Philadelphia Athletics to a new owner who made clear his intention to move the baseball franchise to Kansas City.

That August voters approved a $57.5 million bond improvement program. A $2 million measure included in the package crafted to acquire Blues Stadium received 78% approval.

The Kansas City Athletics debuted there in 1955 and Lamar Hunt first saw the expanded Municipal Stadium in 1957.

The Chiefs moved from Dallas to Kansas City six years later, and Hunt never stopped curating and fine-tuning the Kansas City stadium experience, said Michael MacCambridge, who published a biography of Hunt in 2012.

“It struck me how Lamar had been a son of arguably the richest man in the world at the time (oil tycoon H.L. Hunt),” MacCambridge said recently, “and how he had grown up in a family that was all about oil, and how he had been a dutiful son and had gotten a degree in geology at Southern Methodist University — but also how it had been clear that there was nothing about all that which captured his imagination.

“What had captivated him from early on was just the idea of sports, and the whole ritual surrounding sports.

“That included how people from all walks of life all could come together, where they could go for two to three hours not thinking about anything else — about how the job was going or if you were fighting with your girlfriend — and just focus on that moment.

“Without getting too armchair-psychological about it, stadiums for Lamar represented that sacred space.”

‘Boy-killing’ Sport

On Dec. 16, 1905, J.M. Greenwood, Kansas City superintendent of schools, introduced the following resolution to colleagues:

“Whereas, the killing on the gridiron during the last two months has been 25, injuring seriously more than 140 others, six being killed by concussion of the brain, four by body kicks and blows, three by injuries to the spine, one having his skull crushed, one having his back broken and 10 from other injuries…

“Resolved, that football, as now played is a boy-killing, an educational prostituting and gladiatorial sport that should not be tolerated in high and elementary schools…”

The officials voted in the resolution’s favor, 38 to 8.

The plague of death and serious injury in college and high school football had been biblical.

Fueling Greenwood’s exasperation had been the ordeal experienced on Thanksgiving Day in 1905 by Homer Gibson, a Manual High School student who suffered temporary paralysis and loss of speech after a blow to the head.

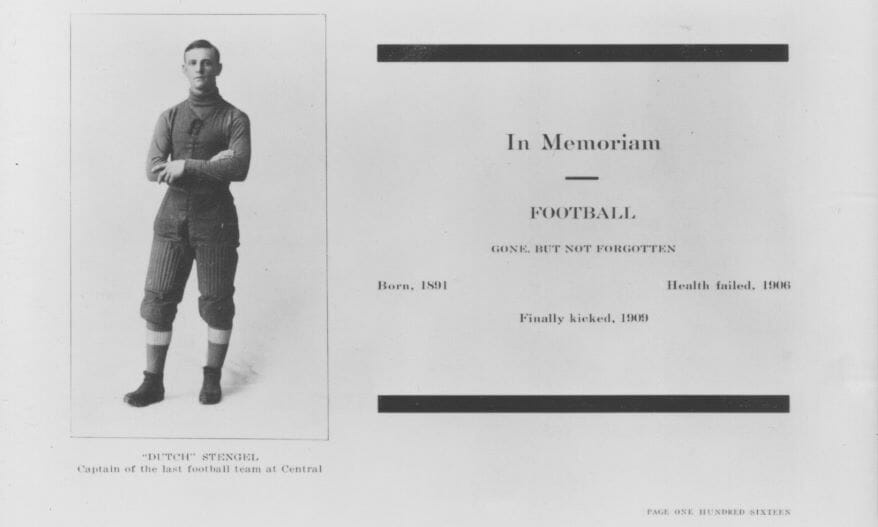

Greenwood’s actions proved unpopular among Central High School athletes who rallied in favor of playing unsanctioned football. They did compete in several approved matches in 1908 and 1909 before school administrators shut the game down for good.

Editors of the 1910 Central High yearbook included an “In Memoriam” page lamenting the death of football, the health of which had “failed” in 1905 and in 1909 had “finally kicked.”

It included the sad-faced photo of the school’s most prominent athlete, Charles “Dutch” Stengel, who some 55 years later — then known as “Casey” — would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Central, along with Manual, Northeast and Westport high schools, fielded football teams again in 1918.

Rule changes and upgraded safety equipment played a role.

So did World War I.

‘War on a Mimic Scale’

The vast international conflict contributed to advances in communication, aviation and related technologies, author Chris Serb told an audience at the National WWI Museum and Memorial last month.

But it also advanced the economic viability of spectator sports.

“World War I led directly to the birth of the NFL,” said Serb, who published “War Football: World War I and the Birth of the NFL,” in 2019. The war, Serb added, “ended up being one of the best things to happen to sports, at least in America, and football was the biggest benefactor.”

Walter Camp, the 1870s Yale College halfback and football innovator whom President Woodrow Wilson in 1917 named as the Navy’s athletic director, saw a connection between the fitness that football required and what doughboys soon would encounter in France.

“To Walter Camp, charging an enemy trench with a bayonet was a lot like plunging into the line with a football,” Serb said, adding that Camp pressed hard to incorporate the sport into the everyday recruit’s training regimen.

“Football is war on a mimic scale,” Camp once wrote, adding, “the same discipline, coordination and quick thinking which was required on the football field is demanded in the service…”

When the United States declared war against Germany, many college athletes enlisted. What the New York Times soon labelled “war football” suggested how their careers could extend beyond their college eligibility.

On Nov. 24, 1917, some 8,000 spectators watched in the snow as the 89th Division team, headquartered at Camp Funston, Kansas, defeated a squad from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, 7-0, at Kansas City’s Association Park, near Lydia and Independence avenues.

Camp Funston, some 120 miles west of Kansas City, was one of many temporary military garrisons or cantonments built in 1917.

Approximately 40,000 soldiers would be trained there.

“I would consider Funston to be the only camp in the Great Plains,” Serb said this week.

“You really had nothing west of Funston until you hit the West Coast, and so you had soldiers from this really broad expanse — Kansas, Missouri, Colorado, Nebraska — and some of them were really good football players.”

In the winter of 1919, to maintain morale among American troops stuck in France following the German surrender the previous November, John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Forces commander, announced a series of sports competitions.

That included a football tournament.

In the championship game in Paris, the 36th Division made up of units from the Texas and Oklahoma National Guard, lost to the Camp Funston 89th Division, 14-6, in what football historians sometimes describe as the first Super Bowl.

The winning athletes who received commemorative gold medals included George “Potsy” Clark, who coached the University of Kansas squad from 1921 through 1925, and Adrian Lindsey, who served as Jayhawks head football coach from 1932 through 1938.

A crowd of some 15,000 fans watched the game, Pershing among them,

By then, football promoters had noted how well-organized games could attract paying customers. A barnstorming tour of the Camp Sherman, Ohio, team, which played in eight stadiums across the state, raised about $150,000 for the war effort.

That likely influenced the football coaches and entrepreneurs who met in Canton, Ohio, in 1920 to form the American Professional Football Association, which two years later became the NFL.

More than 240 “war football” veterans would play or coach in the NFL’s earliest years, Serb said, lending legitimacy to the game that once had been considered the refuge of roughnecks and gamblers.

“Pro football went from being about 20% college players to 75% in less than two years,” said Serb.

In one instance, “war football” would have social ramifications no one could imagine in 1918.

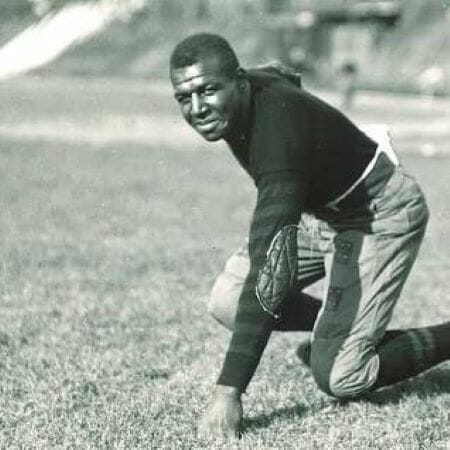

That year rural Missouri native Omar Bradley served as a starting tackle on the Army’s team at Camp Dodge, near Des Moines, Iowa. In his final game, Bradley lined up against Frederick Wayman “Duke” Slater, a University of Iowa star and one of the few Black players then playing major college football.

“A few plays were enough to convince anyone that the best of feelings existed between the pair,” wrote Walter Eckersall, a former football player who then covered the sport for the Chicago Tribune.

“On several occasions Major Bradley helped Slater to his feet when the latter was handled roughly.”

Thirty years later another rural Missouri native, President Harry Truman, directed Bradley — in 1948 U.S. Army chief of staff — to implement his Executive Order 9981, initiating the integration of the U.S. armed forces.

“He did this successfully,” Serb said.

“And I believe the foundations of Bradley’s efforts were laid on that November day in 1918, when he helped Duke Slater to his feet.”

No Room for the ‘Tramp Athlete’

The first NFL game in Kansas City was played not in 1963, when 5,721 fans watched the Chiefs beat the Buffalo Bills in an August preseason Municipal Stadium, but almost 40 years before in 1924 — at the same spot.

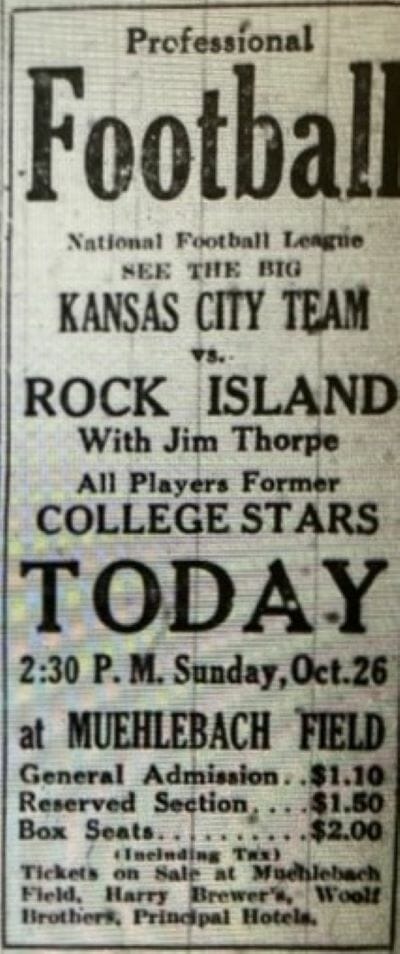

On Oct. 26, 1924, the Kansas City Blues, named after the local minor league baseball team, defeated the Rock Island Independents, 23-7.

A crowd estimated by the Kansas City Star at just under 2,000 paid $2, $1.50 or $1.10 for box, reserved or general admission seats at Muehlebach Field, home of the Blues.

The Independents’ roster on that day included, besides Slater, former Carlisle Indian Industrial School star Jim Thorpe.

But Kansas City didn’t need this variety of football, according to the newspaper column attributed to the “(Kansas City) Star’s Sports Editor,” most likely Clyde E. McBride, Sr., who served in that role from 1915 through 1950.

“Professional football makes a home for the tramp athlete, the alibi athlete, and the disgruntled or flunking high school and college athlete,” the column read.

“Kansas City has plenty of football in the fall, football of the right kind, the academic kind in which the players train to their finest and give to the utmost of their physical strength and courage.”

But the Blues would feature athletes from the universities of Oklahoma, Nebraska and Southern California.

Further, serving as president of the Kansas City Football Co., which operated the team, was Maurice R. Smith, who was both a World War I veteran, (a cadet at the U.S. Army Signal Corps balloon school in Omaha), as well as an Ivy Leaguer who had played at Yale.

Smith, with two partners, each put up $5,000 for the franchise which, Smith told the Star, had been “approved by the Chamber of Commerce.” The Blues, with a record of 2-7, finished 15th in an 18-team league.

In the season finale the Blues lost 17-6 to the Green Bay Packers, which would become one of the league’s most storied franchises.

In the game, a Green Bay player referred to in the Star as only “Lambeau” — doubtless Earl Louis “Curly” Lambeau, a founder of the Packers and for decades the team’s head coach — drop-kicked a 45-yard field goal in the first half and threw for a touchdown in the second.

Some 2,500 spectators paid to watch.

The team canceled its last three scheduled home games but re-branded the following year, playing as the Kansas City Cowboys, re-purposing the name of the city’s National League baseball team of the 1880s.

They spent the entire 1925 season on the road, ending with a 2-5-1 record, and finishing 13th in a 20-team league.

On Nov. 22, some 36,000 fans watched the Cowboys lose 9-3 to the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds. Before the game two of the Cowboys’ stars, Steve Owen and Joe Guyon — both of whom would be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame decades later — wore cowboy regalia while riding horses down Broadway.

“By 1926 the team was pretty good,” said Tom Busch, general counsel for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. That team went 8 and 3, winning both of its home games at Muehlebach Field.

The Cowboys finished fourth in what that year had been a 22-team league.

“But then the league contracted, going down to 12 teams, and Kansas City was dropped,” Busch said.

“It’s interesting that the team had been locally owned,” Busch added. “The history of locally owned Kansas City professional sports franchises is not very long.”

By 1926 editor McBride’s poor opinion of pro football had softened, conceding that the games were entertaining and competently staged.

“But Kansas City hasn’t the population to induce a good professional football team to bring high-priced teams from other cities here,” he wrote.

Still, in 1931 Kansas City voters approved by a four-to-one margin a public improvements package known as the Ten-Year Plan that included money set aside for a new outdoor stadium.

Segregation as a ‘Deal-breaker’

One stadium issue, apparently considered barely newsworthy at the time, was whether every athlete would be welcome to play in Kansas City.

Buried deep in a Kansas City Times story detailing the city’s first NFL game was a paragraph noting how the Rock Island team members believed they might have avoided defeat had Duke Slater been allowed to play.

“Kansas City officials protested before the contest and Slater did not put on a uniform,” the Times reported.

It was the only game that Slater — inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020 — would miss in a 10-year NFL career.

The Jim Crow policy that prevented Slater from playing in 1924 extended to the stands of Blues Stadium, which in the 1930s included signage indicating where Black patrons could sit.

While such policies were not enforced during games played by the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, they were during games of the minor league Kansas City Blues, said author Phil S. Dixon.

As described by Dixon in his 2022 book, “John ‘Buck’ O’Neil: The Rookie, His Words, His Voice,” the change may have been prompted by Ernest L. Brown, a sportswriter for The Kansas City Call, a Black weekly newspaper.

In 1938 Brown published a brief “thank you” to Jacob Ruppert, Blues owner, for removing the signs.

But in the item Brown also alerted Ruppert that Blues Stadium ushers, despite the removal of signage, still were directing Black patrons to the bleachers even after they bought grandstand tickets.

Meanwhile, no Black athletes appeared in NFL games between 1933 and 1946.

“If they were boxers or baseball players, there would be a place for them,” Dixon said.

“But usually there were no places for Black professional football players.”

In those years, accomplished Black athletes found opportunity where they could, Dixon added.

Halley Harding, a Wichita native who played for six Negro Leagues baseball teams between 1926 and 1937, the Monarchs among them, also played on Black semi-pro football teams as well as for the New York Rens, considered the first Black-owned professional basketball team in the 1920s.

By the 1950s one of the most informed individuals regarding segregation in public stadiums was Lamar Hunt.

When he began imagining the American Football League, the rival league eventually established by Hunt and other owners in 1959, he noted those communities which still enforced segregation policies in public facilities.

The Chiefs played its first preseason game on Aug. 9, 1963, the same day Kansas City City Council members hosted a contentious meeting on a public accommodations ordinance.

While council members approved the measure, opponents gathered enough signatures to force a referendum vote.

Kansas City voters narrowly approved the ordinance the following April.

“As somebody who went to the Cotton Bowl every January 1, and also played in games for SMU, Lamar would have been exposed to a lot of stadiums,” MacCambridge said.

“At the time a lot of the stadiums in the South had been non-starters because they were still segregated,” MacCambridge added.

“That was one of the things that had clearly hurt New Orleans and had prevented it from being in Lamar’s plans, either during the time he was planning the AFL or considering where to move the Dallas Texans.

“Those restrictions had been deal-breakers.”

Buying in Big Time

On the day after Christmas, 1962, Hunt checked into the Muehlebach Hotel under an assumed name.

Three days after his Dallas Texans had won the American Football League’s championship, Hunt began negotiating the team’s possible relocation to Kansas City.

Even while winning the AFL, the Texans had lost money while sharing the same market with the Dallas Cowboys.

Kansas City offered a seven-year lease on Municipal Stadium, the first two years at $1 a year. It also agreed to install 3,000 more permanent seats and even build the team a new office and practice facility on the northern end of Swope Park, just south of East 63rd Street.

“To an 8-year-old, that just looked like the most exotic and glamorous building you would ever want to see,” said MacCambridge, who grew up in Kansas City.

“We might laugh about it now because there were maybe only eight to 10 people working in that building, and today NFL teams might have that many people just in the video department.

“But at the time, back in 1963, it was lavish.”

Such follow-through contrasted with the hesitation Kansas City officials had displayed about earlier stadium plans.

While voters approved $750,000 in bonds for a stadium in 1931, it had not been built by 1938. A Star survey that year described the stadium as one of two “least urgent” needs for Kansas City.

The other: a municipal garbage incinerator.

In 1945 the city planning commission first considered a site near the Paseo and Brush Creek — the approximate location of the former Electric Park — as the preferred spot for a new stadium.

But other city officials believed that site would be better served by residential apartment developments.

Then the focus switched to a site near Brush Creek and Cleveland Avenue, where area homeowners protested the feared loss of property values.

Twenty years later, well after the Chiefs had moved to Municipal Stadium, local fans were equally outspoken, but in another way.

During the 1965 season, when the Chiefs would finish third in the four-team AFL Western Division, Hunt began to discern a new level of intensity among Chiefs fans seated in what would later become known as the “Wolfpack” section of Municipal Stadium.

“Lamar recognized that the booing and the heckling indicated a buy-in, a degree of passion on part of the fans who had been eternally disappointed by the baseball team,” said MacCambridge, who this fall will publish “The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America.”

A winning team in Kansas City would be something to shout about.

“This was a time, we have to remember, when the new (Kansas City International) airport hadn’t opened yet and Crown Center hadn’t opened yet,” MacCambridge said.

“And Kansas City had just gotten so beaten down by the baseball team that the Chiefs represented a way — for a city striving to be big-league and to live down its cowtown reputation — to be proud.”

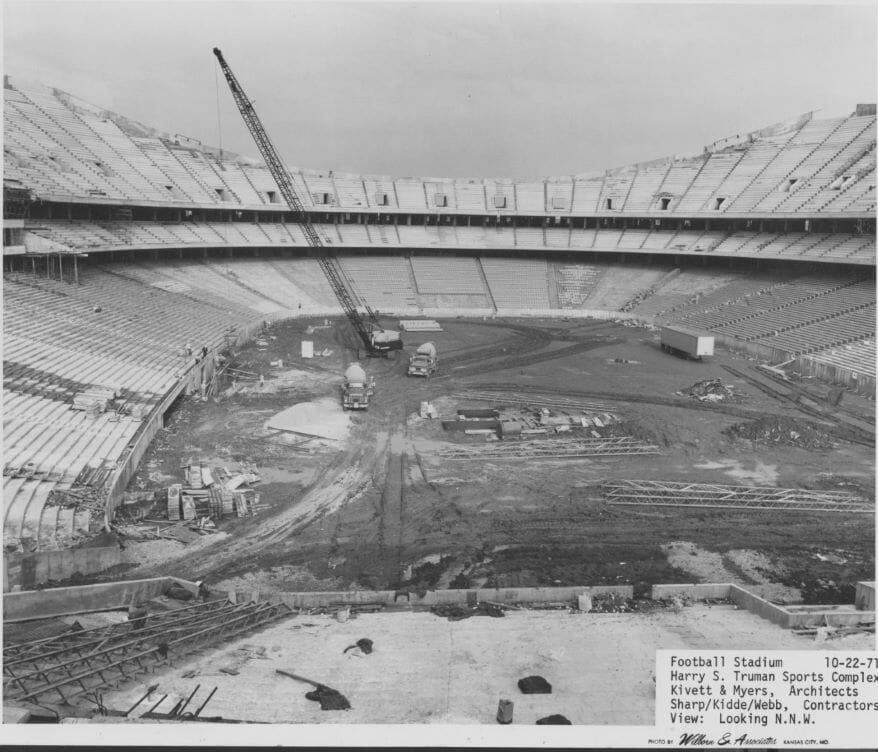

On Jan. 5, 1967, the Jackson County Sports Authority recommended a two-stadium complex be built in eastern Jackson County.

In a letter dated the same day, Hunt pledged to sign a lease for up to 40 years.

“Last season the Chiefs filled Municipal Stadium to 90 percent of capacity,” he wrote. “That sold me that Kansas City is going to be an outstanding pro football city.”

On Jan. 15, the Chiefs played in the first Super Bowl.

About six months later, Kansas City voters approved all seven parts of a $102 million bond issue, the largest part of which had been the $43 million twin-stadium proposal.

Hunt’s enthusiasm had been crucial, in contrast to the lack of commitment shown by Charles O. Finley, owner of the baseball Athletics, according to a Star editorial.

“And finally, here was Lamar Hunt offering a long and generous lease on behalf of the Chiefs, while Charles O. Finley persistently declined to comment on the A’s intentions toward a new stadium…” the Star insisted.

What is now GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium opened in 1972, with Royals Stadium being completed the following spring.

In 2006 Jackson County voters approved a sales tax initiative for renovations at both stadiums. But a measure that would have funded a rolling roof failed by about 4,000 votes, despite a public commitment by the NFL commissioner that — if voters approved the roof — Kansas City would be awarded the 2015 Super Bowl.

“That was the most disappointed I’d ever seen Lamar,” said Bob Moore.

But Hunt would be pleased by the crowds at this week’s NFL draft, he added.

“Today the draft has become the NFL’s second biggest event after the Super Bowl,” Moore said.

“He’d be over the moon.”

Flatland contributor Brian Burnes is a Kansas City area writer and author.